NATIONAL IDENTITY in SCOTTISH and SWISS CHILDRENIS and YDUNG Pedplets BODKS: a CDMPARATIVE STUDY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Das Alte Sempacherlied B

The Ancient Song of Sempach Of bold forefathers in days of old Let their heroic feats be told Of the lance striking home and the clash of swords dire, Of battle dust and the vapor of blood on fire! Our sacred song we dedicate to Winkelried; He is our hero. For us he did bleed. “Look after my wife and child so dear, To you I entrust them without fear!” Calling out to his men before the foe, Strong Struthan grabbed the long spear and forced it low, Burying it in his powerful chest was his decree, To die with God in his heart for the right to be free. And over the body blessed His heroic comrades swiftly pressed On home terrain Swiss swords like lightning fell The murderous horde to quell; And freedom’s victory all hail In all ages hence from mountain to dale. The German lyrics of “The Ancient Song of Sempach” and the following excerpt have been translated by Norman Barry from: Dr. Hans Rudolf Fuhrer’s excellent article “Arnold Winkelried – der Held von Sempach 1386” in PALLASCH, Zeitschrift für Miltärgeschichte [= The Magazine for Military History, published in Salzburg, Austria] (Organ der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Mlitärgeschichte), No. 23, Autumn 2006, p. 71. Was there an historic Arnold von Winkelried? One year later Peter F. Kopp noted that The ground-breaking dissertation by Beat today’s critically-minded historians are Suter entitled “Arnold von Winkelried, the Hero unanimously of the opinion that neither the of Sempach,” completed in 1977, explicitly heroic feat nor a Winkelried can be ascribed to brackets this question out. -

12 Swiss Books Recommended for Translation 3

2012 | no. 01 12 swiss Books Recommended foR tRanslation www.12swissbooks.ch 3 12 SWISS BOOKS 5 les ceRcles mémoRiaux / MeMOrIal CIrCleS david collin 7 Wald aus Glas / FOreSt OF GlaSS Hansjörg schertenleib 9 das kalB voR deR GottHaRdpost / The CalF In the path OF the GOtthard MaIl COaCh peter von matt 11 OgroRoG / OGrOrOG alexandre friederich 13 deR Goalie Bin iG / DeR keepeR Bin icH / the GOalIe IS Me pedro lenz 15 a ußeR sicH / BeSIde OurSelveS ursula fricker 17 Rosie GOldSMIth IntervIeWS BOyd tOnKIn 18 COluMnS: urS WIdMer and teSS leWIS 21 die undankBaRe fRemde / the unGrateFul StranGer irena Brežná 23 GoldfiscHGedäcHtnis / GOldFISh MeMOry monique schwitter 25 Sessualità / SexualIty pierre lepori 27 deR mann mit den zwei auGen / the Man WIth tWO eyeS matthias zschokke impRessum 29 la lenteuR de l’auBe / The SlOWneSS OF daWn puBlisHeR pro Helvetia, swiss arts council editoRial TEAM pro Helvetia, literature anne Brécart and society division with Rosie Goldsmith and martin zingg 31 Les couleuRs de l‘HiRondelle / GRapHic desiGn velvet.ch pHotos velvet.ch, p.1 416cyclestyle, p.2 DTP the SWallOW‘S COlOurS PrintinG druckerei odermatt aG marius daniel popescu Print Run 3000 © pro Helvetia, swiss arts council. all rights reserved. Reproduction only by permission 33 8 MOre unMISSaBle SWISS BOOKS of the publisher. all rights to the original texts © the publishers. 34 InFO & neWS 3 edItOrIal 12 Swiss Books: our selection of twelve noteworthy works of contempo rary literature from Switzerland. With this magazine, the Swiss arts Council pro helvetia is launching an annual showcase of literary works which we believe are particularly suited for translation. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

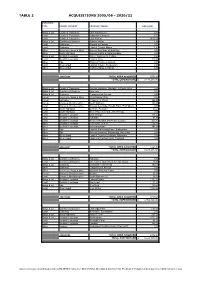

Table 2-Acquisitions (Web Version).Xlsx TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21

TABLE 2 ACQUISITIONS 2005/06 - 2020/21 PURCHASE TYPE FOREST DISTRICT PROPERTY NAME AREA (HA) Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Edra Farmhouse 2.30 Land Cowal & Trossachs Ardgartan Campsite 6.75 Land Cowal & Trossachs Loch Katrine 9613.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders Jufrake House 4.86 Land Galloway Ground at Corwar 0.70 Land Galloway Land at Corwar Mains 2.49 Other Inverness, Ross & Skye Access Servitude at Boblainy 0.00 Other North Highland Access Rights at Strathrusdale 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Scottish Lowlands 3 Keir, Gardener's Cottage 0.26 Land Scottish Lowlands Land at Croy 122.00 Other Tay Rannoch School, Kinloch 0.00 Land West Argyll Land at Killean, By Inverary 0.00 Other West Argyll Visibility Splay at Killean 0.00 2005/2006 TOTAL AREA ACQUIRED 9752.36 TOTAL EXPENDITURE £ 3,143,260.00 Bldgs & Ld Cowal & Trossachs Access Variation, Ormidale & South Otter 0.00 Bldgs & Ld Dumfries & Borders 4 Eshiels 0.18 Bldgs & Ld Galloway Craigencolon Access 0.00 Forest Inverness, Ross & Skye 1 Highlander Way 0.27 Forest Lochaber Chapman's Wood 164.60 Forest Moray & Aberdeenshire South Balnoon 130.00 Land Moray & Aberdeenshire Access Servitude, Raefin Farm, Fochabers 0.00 Land North Highland Auchow, Rumster 16.23 Land North Highland Water Pipe Servitude, No 9 Borgie 0.00 Land Scottish Lowlands East Grange 216.42 Land Scottish Lowlands Tulliallan 81.00 Land Scottish Lowlands Wester Mosshat (Horberry) (Lease) 101.17 Other Scottish Lowlands Cochnohill (1 & 2) 556.31 Other Scottish Lowlands Knockmountain 197.00 Other Tay Land at Blackcraig Farm, Blairgowrie -

Residential Field Trip to Raasay

Residential field trip to Raasay Friday 27th to Monday 30th April 2018 Leader: Dr Brian Bell Friday 27th April We drove to Skye in shared cars and boarded the ferry at Sconser for the twenty-five-minute sail to Raasay. By late afternoon the group had all met up at Raasay House where we would be staying. Saturday 28th April, am. Report by Seonaid Leishman When Brian Bell was asked by Maggie Donnelly to take a GSG excursion to Raasay it was clear that long notice was required, not only to fit in with Brian’s reputation and busy schedule, but because of the popularity of the main accommodation on the Island! We therefore had 18 months to build up high expectations – all of which were all met! The original Macleod house was burned following Culloden and rebuilt in 1747. Boswell, visiting in 1773 states, “we found nothing but civility, elegance and plenty”. Not much has changed. The Raasay House Community Trust has worked hard to set up the Hotel and Outdoor Centre in this elegant building. On the Friday we joined Brian and his colleague Ian Williamson at the House and had the first of many excellent meals followed by an introductory talk in the House library provided for our Group’s use. The Island has well exposed rocks ranging in age from Archaean Lewisian Gneiss, through Torridonian sedimentary rocks, Triassic and Jurassic including Raasay Ironstone and topped by Palaeogene lavas and sills. We would see all these exposures – however not necessarily in the right order! Saturday morning before breakfast photos were urgently being taken of sun on the Red Cuillins – this weather and view wouldn’t change all weekend! The Red Cuillins from Raasay House Brian then explained that because of the sun he wanted to skip sequence and NOT start with the oldest rocks, in order to ensure a great photo that morning on the east coast at Hallaig. -

Download.Php?Id=422 E136d4ac (PDF-Dokument)

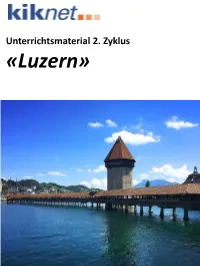

Unterrichtsmaterial 2. Zyklus «Luzern» Luzern 2. Zyklus Lektionsplan Nr. Thema Worum geht es?/Ziele Inhalt und Action Sozialform Material Zeit AB «Die Form des Kreativität fördern anhand mitgebrachter Zeitungen/Zeitschriften Vierwaldstättersees» Gedächtnis anregen, eigene Lernwege zur 1 Icebreaker die Umrisse des Vierwaldstättersees in einer EA/GA Zeitungen/Zeitschriften 20` Erinnerung an die Form des Reisscollage darstellen Leimstifte Vierwaldstättersees zulassen A3-Papier wichtige Kennzahlen und Fakten zum Kanton SuS suchen die verlangten Informationen rund AB «Facts and Figures» und der Stadt finden und kennen um Luzern aus dem Internet zusammen. Lösungen «Facts and Figures» 2 Facts and Figures EA 30` evtl. Vergleich mit dem Selbstständige Korrektur anhand eines PC oder Tablet mit Heimatkanton/Heimatort Lösungsblattes. Internetzugang Erarbeiten und Vertiefen des Wissens über den Tourismus in Luzern und in der Schweiz AB «Gäste aus der Ferne» SuS stellen Mutmassungen über den Tourismus allgemein AB «Deutsch für Luzern-Touristen» Gäste aus der in Luzern an und bringen ihr Vorwissen ein. 3 Fremdsprachenkenntnisse erweitern und GA/Plenum Wörterbücher 45` Ferne SuS erstellen ein eigenes Wörterbuch mit den vertiefen evtl. Zugang zu Online- wichtigsten Begriffen für Touristen in Luzern. Vorwissen in verschiedenen Sprachen Wörterbüchern einbringen AB «Geschichte des Kantons SuS recherchieren selbstständig zu Geschichte des einen Überblick über unterschiedliche -

Grafische Sammlung Historischer Verein Nidwalden Inventar Der Grafischen Sammlung Des Historischen Vereins Nidwalden in Der Kantonsbibliothek

AMT FÜR KULTUR KANTONSBIBLIOTHEK Engelbergstrasse 34, 6371 Stans, Tel 041 618 73 00, www.kantonsbibliothek.nw.ch Grafische Sammlung Historischer Verein Nidwalden Inventar der Grafischen Sammlung des Historischen Vereins Nidwalden in der Kantonsbibliothek Erstellt von Adrian Felber, Heinz Nauer im Sommer / Herbst 2014 Signatur: HGRA Umfang: 638 Grafiken Provenienz: Die Grafische Sammlung ist Teil des Depotbestandes des Historischen Vereins in der Kantonsbibliothek Nidwalden; die allermeisten Grafiken stammen aus dem 18. / 19. Jhd. und wurden vom Historischen Verein zwischen 1864 (Gründungsjahr) und ca. 1910 gesammelt Bemerkungen zum Inventar: Das vorliegende Inventar folgt in seinem Aufbau einem älteren Inventar, welches zwischen 2000 und 2006 von Sibylle von Matt im Rahmen einer umfassenden Restaurierung der Sammlung erstellt wurde. Die Sammlung ist in sechs Formatgruppen („Mini“, „Klein“, „Mittel“, „Normal“, „Gross“, „Überformat“) aufgeteilt. Innerhalb der einzelnen Formatgruppen sind die Grafiken thematisch geordnet. Eine quantitative Übersicht über Formatgruppen und inhaltliche Ordnung findet sich unten. Die Angaben im Inventar zur Herstellungstechnik folgen den handschriftlichen Angaben im Restaurierungsprotokoll von Sibylle von Matt. Im Feld „Bemerkungen“ sind in erster Linie handschriftliche Vermerke auf den einzelnen Grafiken aufgeführt (häufig Datierungen). AMT FÜR KULTUR KANTONSBIBLIOTHEK Engelbergstrasse 34, 6371 Stans, Tel 041 618 73 00, www.kantonsbibliothek.nw.ch QUANTITATIVE ZUSAMMENFASSSUNG MINIFORMAT Schachtel Nr. 1: "Stans" 40 Schachtel Nr. 2: "Kehrsiten, Rotzberg, Stansstad" 26 Schachtel Nr. 3: "Buochs, Beckenried, Niederrickenbach Hergiswil, Pilatus, Engelberg" 31 Schachtel Nr. 4: "Unterwalden, Vierwaldstädtersee" 24. Schachtel Nr. 5: "Trachten" 19 Schachtel Nr. 6: "Gruppen- und Heiligenbilder, Altarbilder" 27 Schachtel Nr. 7: "Winkelried, Scheuber, Pestalozzi und weitere Portraits 32 Schachtel Nr. 8: "Portraits gleicher Serie" 38 Schachtel Nr. -

"I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2011 "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Speth, Alana, ""I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution" (2011). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624392. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-szar-c234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "I Would Cut My Bones for Him": Concepts of Loyalty, Social Change, and Culture in the Scottish Highlands, from the Clans to the American Revolution Alana Speth Nicholson, Pennsylvania Bachelor of Arts, Smith College, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2011 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alana Speth Approved by the Committee L Committee Chair Pullen Professor James Whittenburg, History The College of William and Mary Professor LuAnn Homza, History The College of William and Mary • 7 i ^ i Assistant Professor Kathrin Levitan, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE The radical and complex changes that unfolded in the Scottish Highlands beginning in the middle of the eighteenth century have often been depicted as an example of mainstream British assimilation. -

Scotland's First Settlers

prev home next print SCOTLAND’S FIRST SETTLERS SECTION 9 9 Retrospective Discussion | Karen Hardy & Caroline Wickham-Jones The archive version of the text can be obtained from the project archive on the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) website, after agreeing to their terms and conditions: ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/resources.html?sfs_ba_2007 > Downloads > Documents > Final Reports. From here you can download the file ‘W-J,_SFS_Final_discussion.pdf’. 9.1 Introduction Scotland’s First Settlers (SFS) was set up to look for evidence of the earliest foragers, or Mesolithic, settlement around the Inner Sound, western Scotland. Particular foci of interest included the existence and nature of midden sites, the use of rockshelters and caves, and the different types of lithic raw material (including especially baked mudstone) in use. In order to implement the project a programme of survey and test pitting, together with limited excavation was set up (see Illustration 568, right). Along the way information on other sites, both Prehistoric and later was collected, and this has also been covered in this report. In Illus 568: SFS survey work in addition, a considerable amount of information on the progress. Much of the work changing nature of the landscape and environment has had to be carried out by boat been presented. Fieldwork has finished, data has been analysed. There will always be scope for further work (and this will be discussed later), but the first stages of the project have definitely come to a close. How well has it achieved its aims? 9.2 The major achievements of the project 9.2.1 Fieldwork SFS fieldwork was conducted over a period of five years between 1999 and 2004. -

Verpfuschte Stadt Was Die «Rheinhattan»-Planer Von Bausünden Der Vergangenheit Lernen Können, Seite 6 Editorial 21

Freitag, 21.9.2012 | Woche 38 | 2. Jahrgang 5.– Aus der Community: 38 «Das Herzstück ist eine Fehlplanung. Die S-Bahn muss doch dorthin, wo die ArBeitsplätze sind.» Karl Linder zu «Herzstück soll viel Geld bringen», tageswoche.ch/+bagmn Zeitung aus Basel tageswoche.ch Region Computer-Pannen lassen Lehrer dumm aussehen Überlange Loginzeiten, ServerproBleme, defektes ZuBehör: BaselBieter Lehrer kämpfen mit Computer-ProBlemen – vom Kanton ist keine Hilfe zu erwarten, Seite 23 Interview «Die politische Mitte ist nicht mehr mehrheitsfähig» Der aBtretende Solothurner FDP-Finanzdirektor Christian Wanner zieht nach 35 Jahren in der Politik Bilanz – diese fällt für seine Partei durchzogen aus, Seite 32 Kultur Provokateure nehmen die verletzte Schweizer Seele aufs Korn Die Schweiz hat im Ausland ein ImageproBlem. Zwei Bieler Filmschaffende sind der Sache auf den Grund gegangen – und haBen eine erfrischend freche Satire geschaffen, Seite 44 Foto: Hans-Jörg Walter TagesWoche Zeitung aus Basel Gerbergasse 30 4001 Basel Tel. 061 561 61 61 Verpfuschte Stadt Was die «Rheinhattan»-Planer von Bausünden der Vergangenheit lernen können, Seite 6 Editorial 21. September 2012 Höchste Zeit, über «Rheinhattan» nachzudenken von Remo Leupin, Co-Redaktionsleiter Es sollte augenzwinkernd-jovial herüber- Doch was sind die Alternativen? Die Be völ- kommen, aber der vorwurfsvolle Unterton war kerung wächst, Wohnraum wird knapp, und nicht zu überhören. «Rheinhattan», meinte ein auf In dustrie - und Hafenarealen eröffnen sich leitender Mitarbeiter des Baudepartements neue Nut zungsmöglichkeiten. Wie können diese Remo Leupin kürzlich am Rand einer Debatte zur Stadtent- Gebiete aufgewertet werden, ohne dass kalte wicklung, «ihr von der TagesWoche habt diesen Glas- und Betonburgen entstehen? unmög lichen Begriff in die Welt gesetzt.» In unserer Titelgeschichte sind wir solchen Der Chefbeamte lag falsch. -

Erinnerungen Und Briefe

Diese PDF-Datei ist ein Teil von Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall: Erinnerungen und Briefe Version 1 2011.07 Briefe von 1790 bis Ende 1819 – 3 Bände, Graz 2011 Herausgegeben von Walter Höflechner und Alexandra Wagner Das Gesamtwerk findet sich unter: http://gams.uni-graz.at/hp – 1588 – 2 BRIEFLISTEN Zu den Brieflisten ist zu bemerken, dass die Namen der SchreiberInnen nicht bearbeiteter Briefe in der Regel – wohl auch jener bei BACHOFEN-ECHT – auf Grundlage der Briefunterschriften eruiert wurden und dass in diesem Umstand ein Unsicherheitsfaktor gegeben ist, der bedacht sein will. Dies betrifft natürlich auch die Zuweisung eines Familiennamens an ein bestimmtes Individuum innerhalb dieser Familie, was insbesondere beim Adel problematisch sein kann. Festzuhalten ist weiters, dass die Anzahl der Briefe, wie sie bei BACHOFEN-ECHT angegeben ist, mitunter von der nun tatsächlich eruierten Zahl der Briefe erheblich differiert. – 1589 – 2.1 Verzeichnis der SchreiberInnen von an HP gerichteten Briefen, wie sie bei Bachofen-Echt 546–570 verzeichnet sind, samt darüber hinausgehenden Ergänzungen Anzahl Identifi- der kations- Briefe nummer Namens- und Standesangabe nach BACHOFEN-ECHT bei der Bach- Person ofen- Echt 1 Abdul Hassan, Arabische Briefe 5 2 Abdul Medschid, Sultan, 1839-1861 1 3 Aberdeen G. Hamilton Campbell Earl of, englischer Gesandter in 3 Wien 4 Acerbi Josef Ritter von, k. k. Generalkonsul in in Ägypten 22 5 Ahmet Fethi Pascha, Großmeister der türkischen Artillerie 3 6 Acland Sir Thomas Dyke, Mitglied des englischen Parlamentes 65 7 Acland Leopold, Sohn des vorigen 3 8 Adelburg Edler von, Pera und Wien 5 9 Adelung Friedrich von, russischer Staatsrat 15 10 Aershen Baron (Wien) 1 11 Albani Giuseppe, Bischof von Bologna, Kardinal 1 12 Albarelli Theresa Vordoni, Padua, Verona, ohne Ortsangabe 5 13 Alexander I. -

Detailed Special Landscape Area Maps, PDF 6.57 MB Download

West Highland & Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail na Gàidhealtachd an Iar & nan Eilean Detailed Special Landscape Area Maps Mapaichean Mionaideach de Sgìrean le Cruth-tìre Sònraichte West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Moidart, Morar and Glen Shiel Ardgour Special Landscape Area Loch Shiel Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. Ben Nevis and Glen Coe All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:123,500 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Lynn of Lorn Other Special Landscape Area Other Local Development Plan Areas Inninmore Bay and Garbh Shlios West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Ben Alder, Laggan and Glen Banchor Special Landscape Area Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:201,500 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Loch Rannoch and Glen Lyon Other Special Landscape Area BenOther Nevis Local and DevelopmentGlen Coe Plan Areas West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Ben Wyvis Special Landscape Area Reproduced permissionby Ordnanceof Survey on behalf HMSOof © Crown copyright anddatabase right 2015. All rightsAll reserved.Ordnance Surveylicence 100023369.Copyright GetmappingPlc 1:71,000 Special Landscape Area National Scenic Areas Other Special Landscape Area Other Local Development Plan Areas West Highland and Islands Local