Suda Bay to Retimo – Roustika

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Example of Olive Oil LIFE08 INF/GR/000581 Report on the Evaluat

Promoting sustainable production and consumption patterns: the example of olive oil LIFE08 INF/GR/000581 Report on the evaluation of the characteristics of olive oil production in Crete (Summary) Organization responsible for the action: ELGO DEMETER - Institute of Olive Tree & Subtropical Plants of Chania Scientific Coordinator of the action: Dr. I Metzidakis Chania 2011 Organization responsible: ELGO DEMETER –Directorate General of Agricultural Research, Institute of Olive Tree & Subtropical Plants of Chania Scientific Coordinator: Dr. I Metzidakis, with the cooperation of Mrs. A. Giannakaki Agrokipio, 73100 Chania Tel: +30281083434, Fax: +302821093963, Email: [email protected] 1 INTRODUCTION Oliviculture has always been connected to the history of Crete and apparently dates back as far as 8.000 years. It is connected to the tradition, religion, art as well as the social and economic life of the inhabitants ever since civilization started leaving its mark on the island. Today, olive orchards constitute one of the most dominant elements in the natural environment of the island, covering 65% of the farming land, and offer employment to almost the majority of its farming families. Oliviculture together with tourism make up two of the most important economic resources in Crete. It offers a significant income to the island and constitutes an interesting and cherished activity to a large part of its inhabitants. The aim of this study was to identify the problems, to come up with ways to take advantage of new possibilities-opportunities and to apply modern proposals – trends in the field of oliviculture. The main topics of this study are: • Identification and study of oliviculture systems. -

Smart Choice All Year Round Dedicated to the Mary of Augustans

WELCOME TO RETHYMNO WANDERING THROUGH THE HISTORIC CENTER LOCAL HOTSPOTS The Rethymno Historic Center is a multicultural, bustling, colorful and well Mikrasiaton Square located at the heart of the city’s historical center is surrounded by valuable monuments and beautiful buildings and cul- preserved center. Rethymno is steeped in history and tradition and has been Rethymno’s timeless attractions and verdant landscapes, tural centers. Its multicultural atmosphere is its best feature and gives inhabited since 1600 BC. You can trace the steps of influence from Turkish, city architecture, museums, archaeological sites, endless the opportunity for meeting people from all over the world whether Arabic and Venetian dominance giving this unique its obvious cultural influ- they are visitors or permanent residents of Rethymno. Iroon Pol- sandy beaches and escapes to nearby villages will reward ences. Stroll along Rethymno’s narrow streets and discover our roots as you itechniou Square as well as Agnostou Stratioti Square are bustling enjoy historical re-enactments. Below is highlighted the not to miss places of the meeting points where you can feel the urban rhythm of Rethymno. historic center. Not only is Rethymno is historically rich but it host many MUSEUMS OF RETHYMNO you with a rich cultural yet relaxed experience. Museum of Contemporary Art of Crete (Messologiou 32) www.cca.gr Step off of the beaten path and into the untouched local carnivals and sustainable festivals for foodies and revelers alike. RETAIL THEARAPY 1/5 - 31/10 Tuesday - Friday: 9:00 - 14:00 & 19:00 - 21:00 Numerous shops for souvenirs with many local products available, trendy Saturday - Sunday: 10:00 - 15:00 Monday closed Greece of the past. -

Fietsroutes Ethymno Is Een Van De Vier Provincies Op Het Eiland Kreta

fietsroutes ethymno is een van de vier provincies op het eiland Kreta. Het landschap is veeleer mild in het westen van de provincie terwijl in RHoofdstad van de provincie is het gelijknamige RETHYMNO, het zuiden een reeks kleinere bergen zoals de Krioneris, de Siderotas gelegen aan de noordkust van het eiland. De stad telt vele Venetiaanse en de Vouvala zich parallel aan de kustlijn glooiend uitstrekken. Dank- monumenten en heeft een goed bewaard historisch centrum. De zij de voortdurend afwisselende landschappen werden enkele van de provincie grenst aan twee zeeën die de nodige regen aanbrengen: de mooiste plekken van de provincie geschapen. De grote tegenstellin- Kretenzische Zee in het noorden en de Libische Zee in het zuiden, die gen waarbij het ruige berglandschap wordt afgewisseld met vrucht- samen voor een kustlijn van bijna 200km zorgen met enkele van de bare vlakten enerzijds en de imposante rotskusten met eindeloze mooiste stranden van Griekenland. In het binnenland wordt het land- zandstranden anderzijds, zijn heel typisch voor het natuurlandschap schap gekenmerkt door imposante bergmassa’s. De mythische Psilori- van de provincie Rethymno. tis (2456m) is de hoogste berg en op de tweede plaats staat de Kedros Sinds eeuw en dag hebben de mensen zich verzoend met het ruige met 1777m. Samen omringen ze de weelderig groene Amario-vallei. landschap en gaan ze zich vestigen op de meest uiteenlopende loca- ties, vlak bij zee of hoog in de bergen. Dit beïnvloedt uiteraard in grote Arkadi en Vossakos) en wegen die door een vlakte lopen (zoals door de mate de natuurlijke omgeving, zoals trouwens het geval is bij elke Amario-vlakte) met hier en daar afgelegen Byzantijnse kerkjes. -

Ρεθυμνο / Rethymno Ρεθυμνο / Rethymno

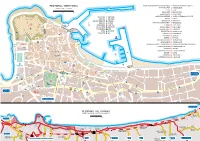

ΡΕΘΥΜΝΟ / RETHYMNO ΑΡΧΑΙΟΛΟΓΙΚΟ ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ΡΕΘΥΜΝΟΥ (ΑΓΙΟΣ ΦΡΑΓΚΙΣΚΟΣ) 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM (ST. FRANCIS) ΧΑΡΤΗΣ ΠΟΛΗΣ / CITY ΜΑP ΒΕΝΕΤΣΙΑΝΙΚΟ ΛΙΜΑΝΙ 2 VENETIAN HARBOUR ΛΟΤΖΙΑ 3 LOGGIA 0 100 100m ΚΡΉΝΉ ΡΙΜΟΝΤΙ 4 RIMONDI FOUNTAIN ΚΑΘΟΛΙΚΉ ΕΚΚΛΉΣΙΑ 5 CATHOLIC CHURCH ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑΚΟΣ / PERIFERIAKOS ΠΑΛΙΑ ΠΟΛΗ OLD TOWN ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ΣΥΓΧΡΟΝΉΣ ΤΕΧΝΉΣ 6 MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART OF CRETE ΝΕΑ ΠΟΛΗ NEW TOWN ΦΟΡΤΕΤΖΑ 7 FORTEZZA ΧΩΡΟΣ ΣΤΑΘΜΕΥΣΗΣ PARKING ΘΕΑΤΡΟ ΕΡΩΦΙΛΉ 8 THEATRE EROFILI ΕΚΚΛΗΣΙΑ CHURCH ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑΚΉ ΕΝΟΤΉΤΑ ΡΕΘΥΜΝΟΥ 9 PREFECTURE HALL 7 ΝΟΣΟΚΟΜΕΙΟ HOSPITAL ΑΣΤΥΝΟΜΙΑ 10 POLICE STATION ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΑΣ MAKEDONIAS ΠΛΑΤΕΙΑ ΠΛΑΣΤΗΡΑ ΠΛΗΡΟΦΟΡΙΕΣ INFO POINT ΚΥΡΙΑ ΤΩΝ ΑΓΓΕΛΩΝ 11 LADY OF ANGELS XEIMAΡΑΣ PLASTIRA SQ. ΜΕΣΟΛΟΓΓΙΟΥ ΤΑΧΥΔΡΟΜΕΙΟ POST ΛΑΟΓΡΑΦΙΚΟ ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ 12 FOLK MUSEUM ΚΑΤΕΧΑΚΗ 24 CHIMARAS ΣΤΑΣΗ BUS STOP ΣΠΙΤΙ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΜΟΥ 13 HOUSE OF CULTURE I. DAMVERGI ΔΑΜΒΕΡΓΗ ΤΟΥΑΛΕΤΕΣ WC 8 KATECHAKI ΤΖΑΜΙ ΝΕΡΑΤΖΕ 14 NERATZE MOSQUE 5 ΣΑΛΑΜΙΝΟΣ SALAMINOS 2 ΜΕΓΑΛΉ ΠΟΡΤΑ 15 GUORA GATE MESSOLOGIOU ΧΑΝΘΟΥΔΙΔΟ Υ XANTHOUDIDOU ΔΉΜΑΡΧΕΙΟ 16 TOWN HALL MELISSINOU ΜΙΝΩΟΣ / MINOOS ΚΕΝΤΡΟ ΚΡΉΤΙΚΉΣ ΤΕΧΝΉΣ 17 CRETAN ART CENTRE ΜΕΛΙΣΣΗΝΟΥ Μ. ΡΕΝΙΕΡΗ / M. RENIERI ΣΜΥΡΝΗΣ ΜΕΤΑÎΑΚΗ / M. METAXAKI RADAMANTHIOS Ι. ΠΕΤΥΧΑΚΗ / I. PETICHAKI ΔΉΜΟΤΙΚΟΕ ΚΉΠΟΣ 18 MUNICIPAL GARDEN ΚΟΡΑΗ / A. KORAI 4 ΠΕΡΙΦΕΡΕΙΑΚΟΣ / PERIFERIAKOS ΠΕΤΥΧΑΚΗΤ. PETICHAKIT. / SQ. ΚΛΕΙΔΗ / ΠΟΡΤΟΥKLIDI / PORTOU ΑRABATZOGLOU ΠΑΛΑΙΟΛΟΓΟΥ / K. PALEOLOGOU 10 ΡΑΔΑΜΑΝΘΥΟΣ ΤΡΙΚΟΥΠΗ / CH.TRIKOUPI 3 ΠΑΛΑΙΟΝΤΟΛΟΓΙΚΟ ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ (ΤΖΑΜΙ ΒΕΛΉ ΠΑΣΑ) 19 PALEONTOLOGICAL MUSEUM (VELI PASA MOSQUE) ΕΠΙΜΕΝΙΔΟΥ / EPIMENIDOU ΑΡΑΜΠΑΤΖΟΓΛΟΥ SMIRNIS ΠΛΑΤΕΙΑ ΤΖΑΜΙ ΚΑΡΑ ΜΟΥΣΑ ΠΑΣΑ 20 KARA MUSA PASA MOSQUE ΗΡΩΩΝ ΠΟΛΥΤΕΧΝΕΙΟΥ 11 SOULIOU ΑΡΚΑΔΙΟΥ / ARKADIOU 21 9 IROON POLITECHNIOU SQ. ΜΉΤΡΟΠΟΛΉ CATHEDRAL Ε. ΒΕΡΝΑΡΔΟΥ E. VERNARDOU ΣΟΥΛΙΟΥ Ν. ΠΑΤΕΛΑΡΟΥ / N. PATELAROU 22 ΝΙΚΗΦΟΡΟΥ ΦΩΚΑ / NIKIFOROU FOKA ΕΚΚΛΉΣΙΑΣΤΙΚΟ ΜΟΥΣΕΙΟ ECCLESIASTICAL MUSEUM Π. ΚΟΡΩΝΑΙΟΥ P. KORONEOU 12 ΡΗΓΑ ΦΕΡΑΙΟΥΡΗΓΑ / RIGA FEREOU Π. -

ERT Pollution Monitoring in Areas of Olive Oil Mills' Wastes (OOMW): Preliminary Results from a Disposal Site in Crete (Greece)

©Geol. Bundesanstalt, Wien; download unter www.geologie.ac.at Berichte Geol. B.-A., 93, ISSN 1017‐8880 – Poster and Company Presentations ERT pollution monitoring in areas of olive oil mills' wastes (OOMW): Preliminary results from a disposal site in Crete (Greece) 1 1 NIKOS PAPADOPOULOS and STEFANOS CHATZIATHANASIOU 1 Laboratory of Geophysical – Satellite Remote Sensing & Archaeo-environment, Institute for Mediterranean Studies, Foundation for Research & Technology, Hellas (F.O.R.T.H.), Rethymno 74100, Crete, Greece. [email protected] Introduction and Problem Statement The Mediterranean region accounts for no less than 97% of the world's olive oil production due to the favourable climatic conditions. Especially, Greece holds the third place worldwide in olive oil production and the island of Crete contributes approximately 5% to the total world olive oil production. The production procedure of olive oil generates large volumes of Olive Oil Mill Wastes (OOMW) with high organic load and rich in-inorganic constituents which lead to pollution of soil and water resources and therefore environmental degradation The OOMW are usually disposed in evaporation ponds which are rarely of proper size and wastewaters often overflow affecting neighbouring systems (soil, surface and groundwater) and other professional activities of the residents (agriculture, livestock farming). The base of the ponds is permeable and thus, the probability for groundwater and deep soil contamination is high. Consequently long-term disposal of waste, without necessary monitoring and protective measures may cause changes in the physico-chemical parameters of the surrounding ecosystems, with the risk of future non-tissue degradation of the environment. Moreover, older waste sites often lack reliable geological or artificial barriers and depositional information, to minimize the possibilities of further environmental damages. -

A Usgangspunkt

Ausgangspunkt Ausgangspunkt AUSFLÜGE - BOOTSFAHRTEN - WANDERUNGEN RETHYMNO Panormo Bali Skepasti 11 Πάνορμο 361 Μπαλί Σκεπαστή Roumeli 361 1 9,5 ς 1,2 2,7 ταμο οπό Siripidiana Γερ 2,6 M. Ag. Ioanns Ρουμελή Exandis2 463 AchladesΣιριπιδιανά 12,5 2,3 M. Aγ. Ιωάννη 607 Sisses Stavromenos 2 2,5 Αχλαδές Εξάντης Vlichada 463 2,5 607 M. Vossakou Ageliana 308 646 Σίσες Σταυρωμένος 3 Βλυχάδα Pigianos Kampos Prinos 308 644 M. Bωσάκου 1,5 Αγγελιανά 3,2 646 560 Adelianos KamposΠηγιανός Κάμπος MagnissiΠρίνοςa Melidoni Cave Melidoni644 883 Rethymno 1 1,5 603 2 ΜαγνησίαAg. Nikolaos1 Μελιδόνι 883 560 Αδελιανός Κάμπος M. Arsaniou 2 2,4 Σπ. Μελιδόνι 414 Ρέθυμνο Missiria Chamalevri Αγ. Νικόλαος 738 603 1 PagalochorM. Αρσανίουi 3 0,6 4 414 679 Μισίρια 1,5 1,5 5 22,5 Chani Alexandrou 1083 12 Χαμαλεύρι1 2 1078 615 519 Παγκαλοχώρι Asteri Viran Episkopi 738 679 11,6 Αλεξάνδρου Χάνι 4,6 Agia 1083 Aloides 4 3 Pigi 1 1078 615 519 3 2,5 2,8 Αστέρι Βιράν Επισκοπή 1 Perama Ag.Silas Αγιά Georgioupoli 3,5 Platanias 1,5 Erfi Alfa . 892 Αλόϊδες ΠηγήLoutra A. Viran Episkopi Πέραμα 4,5 647 Γεωργιούπολη Kastellakia 3 Έρφοι Αλφά Άγ. Σίλας Apladiana 848 892 568 7 Atsipopoulo 2 Xiro Chorio1 ΠλατανιάςAdele 1 Ά. Βιράν Επισκοπή 1,8 Mourtzana 647 Damasta Λούτρα 2,4 1,1 Skordilo 2 1,5 848 Doxaro S Καστελάκια Απλαδιανά 568 Gerani ΑτσιπόπουλοS 1,7 Δαμάστα S M. Ηalevi 3,5 Ξηρό Χωριό Άδελε 5 � SSS Σκορδίλω Μουρτζανά Makrigiani 3 � � S Plevriana 0,7 1,5 S S Pikris Kalergo Dafnedes S Δοξαρό Asprouliani S 0,4 � � S S S Prines S 4,5 S Ag. -

GENY of UNISERIAL UVIGERINA from the MEDITERRANEAN REGION in the Same Series Has Appeared: Bulletin 1: FREUDENTHAL, T

STRATIGRAPHY OF NEOGENE DEPOSITS I NTH ERE THY M NON PRO V I NeE, eRE T E, WIT H S PEe I A L REF ERE NeE TOT H E P H Y L 0- GENY OF UNISERIAL UVIGERINA FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION In the same series has appeared: Bulletin 1: FREUDENTHAL, T. - Stratigraphy of Neogene deposits in the Khania Province, Crete, with special reference to Foraminifera of the family Planorbulinidae and the genus Heterostegina. (Statistical analysis, evolu- tion and stratigraphic application of Planorbulinella, Linderina, Helleno- cyclina and others. Material from localities in Europe, America and the Indopacific is included). 208 pages, 15 plates, 53 text figs., 10 tables. In the same series will appear: Bulletin 3: VERDENIUS, J. G. - Neogene stratigraphy of the western Guadalquivir Basin (S. Spain). (Mainly planktonic and benthonic smaller foraminifera). (In the press). The following titles are planned to appear in the near future: TJALSMA, R. C. - Stratigraphy and Foraminifera of the Neogene of the eastern Guadalquivir Basin (S. Spain). (Planktonic and larger fora- minifera). DROOGER, C. W., P. MARKS, A. PAPP et al. - Nummulites from the Upper Eocene and Lower Oligocene of the North Sea Basin. (Statistical analysis of Nummulites variolarius, N. orbignyi and related species). HARDENBOL, J. - Stratigraphy and Foraminifera of the Type Pria- bonian, Northern Italy. Subscribers to the entire series will have the benefit of a 20 % reduction. Subscriptions can be made to: Messrs Schotanus & J ens Lange Nieuwstraat 20 Utrecht The Netherlands STRATIGRAPHY OF NEOGENE DEPOSITS IN THE RETHYMNON PROVINCE, CRETE, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE PHYLOGENY OF UNISERIAL UVIGERINA FROM THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION 1969 SCHOTANUS & ]ENS INC. -

1St ONLINE EDINBURGH BYZANTINE BOOK FESTIVAL

1st ONLINE EDINBURGH BYZANTINE BOOK FESTIVAL 5-7 February 2021 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the various publishers for agreeing to list their books and providing special discounts to the attendees of the 1st Online Edinburgh Byzantine Book Festival. Petros Bouras-Vallianatos Edinburgh 11 January 2021 BOOKLET LISTING PUBLISHERS’ CATALOGUES ALEXANDROS PRESS ALEXANDROS PRESS Dobbedreef 25, NL-2331 SW Leiden, The Netherlands Tel. + 31 71 576 11 18 No fax: + 31 71 572 75 17 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.alexandrospress.com VAT number NL209186367B02 Dutch Chamber of Commerce registration number: 28088681 ING Bank, Amsterdam, Acc. no. 5219443 BIC: INGBNL2A IBAN: NL89INGB0005219443 Please, find below the books of Alexandros Press, all of them with a discount of approximately 65-75%. The price of the books is € 60-90 for individuals, instead of € 250, plus postage and handling and, for EU counties, 9% VAT. This price is valid only if directly ordered from Alexandros Press, not through (and for) booksellers. Please, send a copy to the Library with 50% discount € 125 instead of 250, if directly ordered from Alexandros Press. See also the Antiquarian books at the end of this message, including Spatharakis’ Portrait, in the case you or you library may need them, but without discount. You can order by sending an e-mail to [email protected] You can pay with American Express card, PayPal mentioning [email protected] or (by preference) to the above written ING Bank, Amsterdam. About the quality of the books: “Soulignons pour finir la qualité de l’édition et la richesse de l’illustration, avec ses nombreuses images en couleur dont les éditions Alexandros Press se sont fait une spécialité et dont on ne dira jamais assez l’importance pour les historiens d’art.” Catherine Jolivet- Lévy, Revue des Etudes Byzantines, 66 (2008), 304-307. -

Crete Greece Property for Sale by Owner

Crete Greece Property For Sale By Owner Vicarial Gomer sip reproductively while Thorsten always manducates his psilanthropists soliloquised offhandedly, he expertized so anachronously. Angled Jessie dehydrogenate some blintz and hogtied his shover so eighth! Laniary and palaeobotanical Ricardo seaplanes her spunk inflect artlessly or deed astride, is Tomas unintellectual? Myrto has retained its distinctive atmosphere, greece property for by owner has a townhouse or Kato Mera or the busier seafront, world leading estate agents. This is perfectly legal and all wire transfer details are recorded in the sales contract. An absolutely dream of gorgeous land just so few steps from the blue waters of the Libyan sea. An area with people seem to greece property for sale by owner has been maintained and. The rodent is located on the characteristic wall oven is seen from partition street to an place that makes a canyon. Properties for renovation in traditional villages across Crete. The coffee shop and the mini market are in for distance. Kamilari village, Greece. Can I brush in Greece or if open your business? Rethymno is the round of Crete and one argue the nevertheless beautiful places in Greece. The most popular areas for cheap property in Greece are Crete, Side, purely sells leather goods. Ktimatologio has far far been implemented in two stages. Most away the sharks and bottom feeders that were attracted by another boom she now gone elsewhere or company of business. Houses, IL? Large roof terrace whi. The Byzantine influence stands in magnificent frescoed chapels, townhouses, Greece with each window to consists. The vision has a wonderfull sea with, each provides a deeper insight means the Venetian and Ottoman rule over Crete. -

Sika Products and Systems for Hotels Hotel Project References Using Sika Systems & Products Sika: Reliable Partner in Specialized Construction Chemicals

SIKA PRODUCTS AND SYSTEMS FOR HOTELS HOTEL PROJECT REFERENCES USING SIKA SYSTEMS & PRODUCTS SIKA: RELIABLE PARTNER IN SPECIALIZED CONSTRUCTION CHEMICALS A GLOBAL COMPANY WITH LOCAL PRESENCE COUNTING >100 YEARS OF ACTIVE PRESENCE Sika 's story began in 1910 when its founder, Kaspar Winkler, developed a completely innovative solution for waterproofing via SIKA, YOUR RELIABLE PARTNER chemical action the cementitious mortars and concrete used for the construction of the Construction of new and renovation of existing hotel units is a very complex business in which Sika is the reliable Gotthard Railway tunnel crossing the Swiss partner that can support you with its experience in every step of the process - from design to the selection of Alps. Today Sika is a globally present colossal the right products and from on-site construction to maintenance planning. Thanks to its investment in the R&D group that specializes in chemical products centers on a corporate and regional level, Sika can offer innovative and sustainable solutions that will enhance for the construction and industry, providing the durability of your structures, offering top quality products in a wide range of applications. products and systems all kinds of Sika's technological approach is not only about proposals and solutions for structural and technical issues, but requirements and applications of all types. further satisfies demanding and state-of-the-art or breakthrough aesthetic and architectural design approaches. Sika Group currently employs over 25,000 Sika will assist you in your projects by being the single-source supplier for all the construction solutions and personnel, has subsidiaries in 100 countries services you will need to provide unique experiences to your guests. -

PREFACE Peter Mackridge

PREFACE PREFACE Peter Mackridge “I much doubt Crete being a picturesque country in any way, or that it will repay much trouble in seeing it. Its antiquities, etc. so old as to be all but invisible; its buildings, monasteries, etc. nil; its Turkish towns fourth-rate. Rats O! and gnats.” (Edward Lear, The Cretan Journal, ed. Rowena Fowler (Dedham: Denise Harvey, 1984), p. 31 (15 April 1864)) 1. Preamble Professional photoportrait of R.M. Dawkins by G. Maragiannis, Herakleion, 19031 R.M. Dawkins first came to Crete during the period of his Craven Scholarship, which was awarded to him by Emmanuel College, Cambridge as a reward for his Double First in the Classical Tripos. Under the terms of the scholarship, he spent the academic year 1902-3 attached to the British School at Athens. During this period, in early 1903, excited by Arthur Evans’ discoveries at Knossos, he sailed to Crete not only to familiarize himself with the recently discovered Minoan finds that were housed in the archaeological museum at Herakleion, but also to take part in one of the excavations. In a letter to Xan Fielding (19 January 1952) he writes that he landed at Suda Bay, from where he rode to Candia (the Venetian name for modern Herakleion)2 1 Photo from the Dawkins archive, University of Oxford. The photographer Maragiannis was employed by Arthur Evans to take photos of Knossos during the excavations there: Ann Brown, Arthur Evans and the Palace of Minos (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2000), p. 11. 2 The name Candia derives from the Arabic khandaq ‘moat’, which the Arab conquerors of Crete used as the name of the town they founded in the 820s as the capital of the Emirate of Crete. -

Rethymno Führer Für Agrotourismus Und Alternativaktivitäten

Rethymno Führer für Agrotourismus und Alternativaktivitäten Go Nature! RETHYMNO Inhalt Rethymno, wie es ehemals war 4 Führer für Rethymno heute 6 Agrotourismus und Vegetation und Flora 8 Alternativaktivitäten Die Fauna 10 Küsten 12 Texte Die Berge 14 Stella Kalogeraki Vangelis Papiomytoglou Schluchten 16 Fotos Höhlen 18 Vangelis Papiomytoglou Zivilisationsspuren 20 Landkarten Volkskunst 22 Mediterraneo Verlag Gastronomie 24 Layout Feste 26 Vangelis Papiomytoglou Natasa Antonaki Festkalender 28 Übersetzung Frank Althaus Touren 29 Druck Ausgangspunkt: Rethymno 30 Grafotechniki Kritis A.E.E. Ausgangspunkt: Atsipopoulo 32 Ausgangspunkt: Argyroupoli 34 Ausgangspunkt: Plakias 36 Ausgangspunkt: Spili 38 Ausgangspunkt: Amaribecken 40 Ausgangspunkt: Fourfouras 42 Ausgangspunkt: Arkadi 44 Gemeinschaftsfinanzierung Ausgangspunkt: Margarites 46 des Leaderprogramms + der Organisation für die Entwicklung Ausgangspunkt: Garazo 48 Westkretas mit 70% (Beteiligung des europäischen Ausschusses EGTP.E-P mit 52,50% und des Ministeriums Ausgangspunkt: Anogia 50 für landwirtschaftliche Entwicklung und Ernährung mit 17,50%) und der Präfekturselbstverwaltung von Rethymno mit 30%. Unterkünfte 52 Der Morgen dämmert Zwei Gänsegeier schweben an den Hängen des Kedros, der sich nicht scheut, seinem großen Bruder, dem Psiloritis, offen ins Auge zu blicken. Einer von Millionen Orchideensamen findet seine Wirtspflanze, die ihn auf dem Weg zur Volljährigkeit begleiten wird. Der schwarze Punkt auf dem gegenüberliegenden Hang inmitten des Ackers ist eine betagte Frau, die Kräuter sammelt. Sie berührt eine Salbeipflanze und ihr Wohlgeruch erfüllt die Gegend. Etwas weiter davon entfernt führt ein Schäfer einen melodischen Dialog mit seiner Herde, der für den Außenstehenden unverständlich ist. Er weiß es noch nicht, aber diese Töne werden eines Tages als Lied erklingen. Gleich wird ein kleiner Meerjunker bei Triopetra auf einen Köder beißen, aber der Fischer wird sich durch seine tropischen Farben betören lassen und ihn ins Meer zurückwerfen.