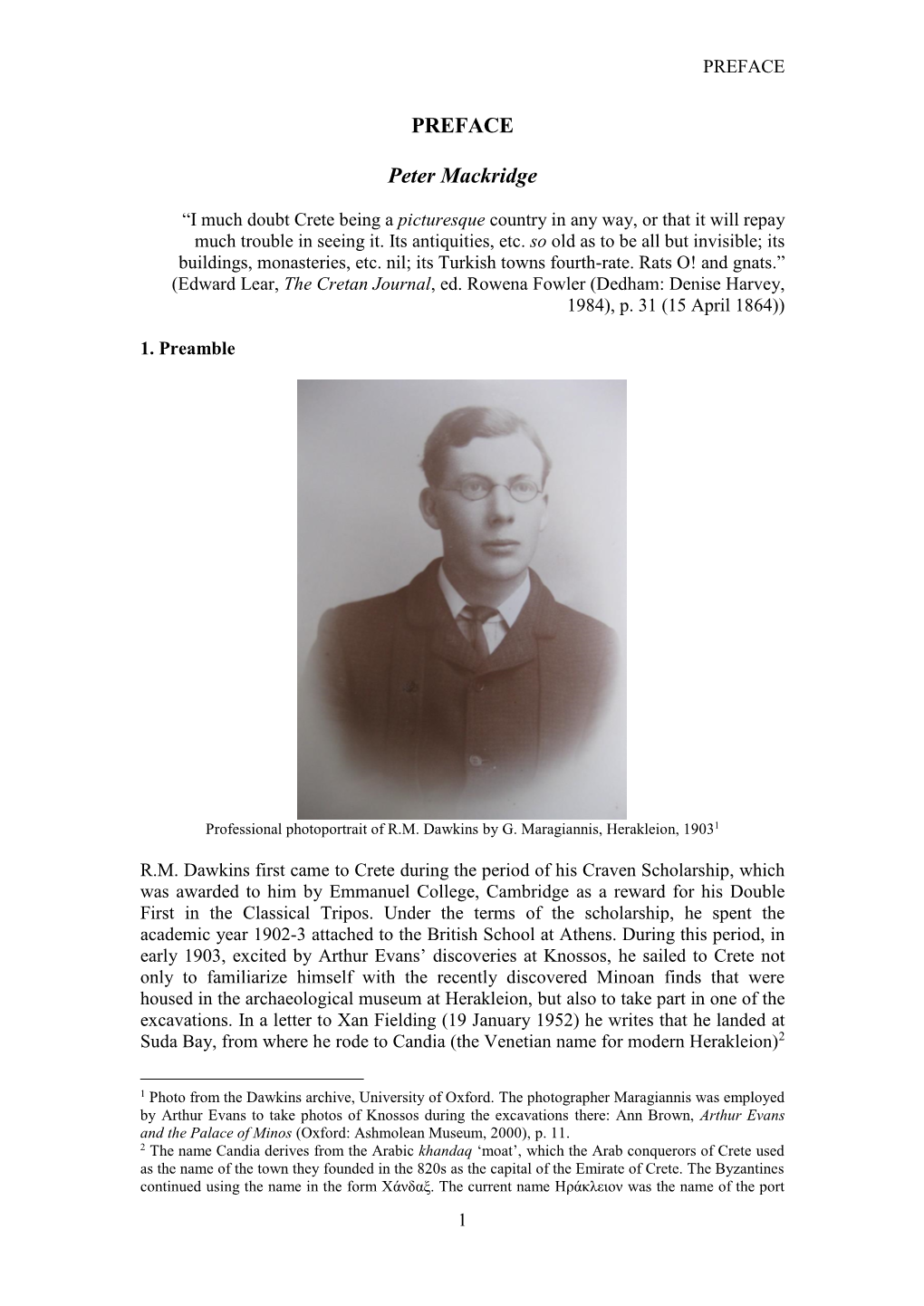

PREFACE Peter Mackridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pre-Trip Extension Itinerary

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Enhanced! Northern Greece, Albania & Macedonia: Ancient Lands of Alexander the Great 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! Northern Greece, Albania & Macedonia: Ancient Lands of Alexander the Great itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: As I explored the monasteries of Meteora, I stood in awe atop pinnacles perched in a boundless sky. I later learned that the Greek word meteora translates to “suspended in the air,” and that’s exactly how I felt as I stood before nature’s grandeur and the unfathomable feats of mankind. For centuries, monks and nuns have found quiet solitude within these monasteries that are seemingly built into the sandstone cliffs. You’ll also get an intimate view into two of these historic sanctuaries alongside a local guide. Could there be any place more distinct in Europe than Albania? You’ll see for yourself when you get a firsthand look into the lives of locals living in the small Albanian village of Dhoksat. First, you’ll interact with the villagers and help them with their daily tasks before sharing a Home-Hosted Lunch with a local family. While savoring the fresh ingredients of the region, you’ll discuss daily life in the Albanian countryside with your hosts. -

Crete 8 Days

TOUR INFORMATIONS Crete White mountains and azure sea The village of Loutro village The SUMMARY Greece • Crete Self guided hike 8 days 7 nights Itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0001 HIGHLIGHTS Chania: the most beautiful city in Crete The Samaria and Agia Irini gorges A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxation and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 13 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 13 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Wild, untamed ... and yet so welcoming. Crete is an island of character, a rebellious island, sometimes, but one that opens its doors wide before you even knock. Crete is like its mountains, crisscrossed by spectacular gorges tumbling down into the sea of Libya, to the tiny seaside resorts where you will relax like in a dream. Crete is the quintessence of the alliance between sea and mountains, many of which exceed 2000 meters, especially in the mountain range of Lefka Ori, (means White mountains in Greek - a hint to the limestone that constitutes them) where our hike takes place. Our eight-day tour follows a part of the European E4 trail along the south-west coast of the island with magnificent forays into the gorges of Agia Irini and Samaria for the island's most famous hike. But a nature trip in Crete cannot be confined to a simple landscape discovery even gorgeous. It is in fact associate with exceptional cultural discoveries. The beautiful heritage of Chania borrows from the Venetian and Ottoman occupants who followed on the island. -

Arkadi Monastery and Amari Valley)

10: RETIMO TO AGHIA GALINI CHAPTER 10 RETIMO TO AGHIA GALINI (ARKADI MONASTERY AND AMARI VALLEY) Arkadi Monastery before its destruction in 1866 (Pashley I 308-9) Arkadi Monastery since its reconstruction (Internet) 1 10: RETIMO TO AGHIA GALINI ARKADI. April 4th 19171 Rough plan made at first visit A. The place where the explosion was B. New guest-house C. Church D. Refectory where there was a massacre E. Heroon F. Outbuilding with Venetian steps G. Main entrance H. Back entrance I. Place of cannons Ten kilometres east of Retimo the road to Arkadi branches off inland and in 2 hours one gets to the monastery (note: I came the reverse way on this first visit). At this point there is a high rolling plateau 500 metres above the sea and quite near the north edge of this is the monastery. A new church ten minutes north of the monastery is nearly on the edge of this plateau. At a later visit I came to Arkadi from, I think, Anogia and lost the way a good deal and arrived in the evening by recognising this new church and making for it, as it is conspicuous a long way off whilst the monastery itself is hidden from the north and east by the rising ground upon which this church stands. It can be seen from the sea, but the monastery itself cannot. A gorge wooded with scrub cuts into this plateau and almost at the top of this gorge at its east side is Arkadi. From the gorge one sees only the Heroon and the tops of a few trees by the moni. -

Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia

12/23/2018 Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia Special Operations Executive The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British World War II Special Operations Executive organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing Active 22 July 1940 – 15 secret organisations. Its purpose was to conduct espionage, sabotage and January 1946 reconnaissance in occupied Europe (and later, also in occupied Southeast Asia) Country United against the Axis powers, and to aid local resistance movements. Kingdom Allegiance Allies One of the organisations from which SOE was created was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret "stay-behind" resistance Role Espionage; organisation, which would have been activated in the event of a German irregular warfare invasion of Britain. (especially sabotage and Few people were aware of SOE's existence. Those who were part of it or liaised raiding operations); with it are sometimes referred to as the "Baker Street Irregulars", after the special location of its London headquarters. It was also known as "Churchill's Secret reconnaissance. Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". Its various branches, and Size Approximately sometimes the organisation as a whole, were concealed for security purposes 13,000 behind names such as the "Joint Technical Board" or the "Inter-Service Nickname(s) The Baker Street Research Bureau", or fictitious branches of the Air Ministry, Admiralty or War Irregulars Office. Churchill's Secret SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except Army where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal Allies (the United Ministry of States and the Soviet Union). -

Honeymoon & Gastronomy2

Explore Kapsaliana Village Learn More Kapsaliana Village Hotel HISTORY: Welcome at Kapsaliana Village Hotel, a picturesque village in The story begins at the time of the Venetian Occupation. Kapsaliana Rethymno, Crete that rewrites its history. Set amidst the largest olive Village was then a ‘metochi’ - part of the Arkadi Monastery estate, the grove in the heart of the island known for its tradition, authenticity and island’s most emblematic cenobium. natural landscape. Around 1600, a little chapel dedicated to Archangel Michael is Located 8km away from the seaside and 4km from the historic Arkadi constructed and a hamlet began to develop. More than a century monastery. Kapsaliana Village Hotel is a unique place of natural beauty, later, in 1763, Filaretos, the Abbot of Arkadi Monastery decides to peace and tranquility, where accommodation facilities are build an olive oil mill in the area. harmonised with the enchanting landscape. The olive seed is at the time key to the daily life: it is a staple of Surrounded by lush vegetation, unpaved gorges and rare local herbs nutricion, it is used in religious ceremonies and it functions as a source and plants. Kapsaliana Village Hotel overlooks the Cretan sea together of light and heat. with breathtaking views of Mount Ida and the White Mountains. More and more people come to work at the mill and build their The restoration of Kapsaliana Village hotel was a lengthy process which houses around it. The settlement flourishes. At its peak Kapsaliana took around four decades. When the architect Myron Toupoyannis, Village Hotel boasts 13 families and 50 inhabitants with the monk- discovered the ruined tiny village, embarked on a journey with a vision steward of the Arkadi monastery in charge. -

The Greek World

THE GREEK WORLD THE GREEK WORLD Edited by Anton Powell London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1997 Selection and editorial matter © 1995 Anton Powell, individual chapters © 1995 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Greek World I. Powell, Anton 938 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data The Greek world/edited by Anton Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Greece—Civilization—To 146 B.C. 2. Mediterranean Region— Civilization. 3. Greece—Social conditions—To 146 B.C. I. Powell, Anton. DF78.G74 1995 938–dc20 94–41576 ISBN 0-203-04216-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-16276-5 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06031-1 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-17042-7 (pbk) CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Notes on Contributors viii List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Anton Powell PART I: THE GREEK MAJORITY 1 Linear -

NATURA 2000 Network in Crete an Altitude of 1,700M

MOUNTAINOUS AND INLAND SPECIAL AREAS OF INSULAR, COASTAL AND WETLAND AREAS CONSERVATION AND SPECIAL PROTECTION AREAS The coastal and wetland areas established in the NATURA 2000 Crete’s main characteristic is its three mountain massifs (the Lefka Network are entirely different in appearance. Low rocky expanses Ori, Psiloritis and Dikti), consisting mainly of limestone ranges with covered mainly in phrygana alternate with long beaches (ideal nesting a variety of habitats and high biodiversity. The heavily sites for Caretta Caretta Loggerhead sea turtles), dominated by saline karstified limestone terrain features resistant plant species, which occur on the sandy coasts. The steep numerous mountain plains, dolines, limestone cliffs are home to numerous chasmophytes, many of which gorges and caves, all characteristic are endemic, while sea caves even provide a refuge for Mediterranean of the Cretan monk seals (Monachus monachus). The rivers in the west and torrents landscape. in the east create estuary zones of varying sizes, rich in aquatic riparian plants, ideal for hosting of rare waterbirds, as well as characteristic habitats such as forests of Cretan palm (Phoenix theophrasti). The above mountain chains are covered with relatively sparse forests Crete’s satellite islands are of considerable aesthetic and biological Development and Promotion of the of Calabrian pine (Pinus brutia), cypress (Cupressus sempervirens), value. Alongside typical Greek and Cretan plant species, they are also prickly-oak (Quercus coccifera) and maple (Acer sempervirens) up to home to legally protected North African species. Significant habitats NATURA 2000 Network in Crete an altitude of 1,700m. Near the peaks the dominant vegetation is found on most islands include the groves of juniper (Juniperus spp.) mountain phrygana, while precipices and gorge sides are covered in growing on sandy and rocky beaches, as well as the expansive crevice plants (chasmophytes), most of which are species endemic Posidonia beds (Posidonia to Crete. -

Revolt and Crisis in Greece

REVOLT AND CRISIS IN GREECE BETWEEN A PRESENT YET TO PASS AND A FUTURE STILL TO COME How does a revolt come about and what does it leave behind? What impact does it have on those who participate in it and those who simply watch it? Is the Greek revolt of December 2008 confined to the shores of the Mediterranean, or are there lessons we can bring to bear on social action around the globe? Revolt and Crisis in Greece: Between a Present Yet to Pass and a Future Still to Come is a collective attempt to grapple with these questions. A collaboration between anarchist publishing collectives Occupied London and AK Press, this timely new volume traces Greece’s long moment of transition from the revolt of 2008 to the economic crisis that followed. In its twenty chapters, authors from around the world—including those on the ground in Greece—analyse how December became possible, exploring its legacies and the position of the social antagonist movement in face of the economic crisis and the arrival of the International Monetary Fund. In the essays collected here, over two dozen writers offer historical analysis of the factors that gave birth to December and the potentialities it has opened up in face of the capitalist crisis. Yet the book also highlights the dilemmas the antagonist movement has been faced with since: the book is an open question and a call to the global antagonist movement, and its allies around the world, to radically rethink and redefine our tactics in a rapidly changing landscape where crises and potentialities are engaged in a fierce battle with an uncertain outcome. -

27253 ABSTRACT BOOK Nuovo LR

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Oct 09, 2021 Molecular determination of grey seal diet in the Baltic Sea in relation to the current seal-fishery conflict Kroner, Anne-Mette; Tange Olsen, Morten; Kindt-Larsen, Lotte; Larsen, Finn; Lundström, Karl Published in: Abstract book of the 32nd Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Kroner, A-M., Tange Olsen, M., Kindt-Larsen, L., Larsen, F., & Lundström, K. (2018). Molecular determination of grey seal diet in the Baltic Sea in relation to the current seal-fishery conflict. In Abstract book of the 32nd Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society (pp. 110-110). European Cetacean Society. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. MARINE CONSERVATION FORGING EFFECTIVE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS ECS European Cetacean Society The 32nd Conference LA SPEZIA 6th April to 10th April 2018 2018 THE 32ND CONFERENCE OF THE EUROPEAN CETACEAN SOCIETY LA SPEZIA, ITALY 6th April to 10th April 2018 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME ECS nd European Cetacean Society The 32 Conference LA SPEZIA 6th April to 10th April 2018 2018 Photo: C. -

Heraklion (Greece)

Research in the communities – mapping potential cultural heritage sites with potential for adaptive re-use – Heraklion (Greece) The island of Crete in general and the city of Heraklion has an enormous cultural heritage. The Arab traders from al-Andalus (Iberia) who founded the Emirate of Crete moved the island's capital from Gortyna to a new castle they called rabḍ al-ḫandaq in the 820s. This was Hellenized as Χάνδαξ (Chándax) or Χάνδακας (Chándakas) and Latinized as Candia, the Ottoman name was Kandiye. The ancient name Ηράκλειον was revived in the 19th century and comes from the nearby Roman port of Heracleum ("Heracles's city"), whose exact location is unknown. English usage formerly preferred the classicizing transliterations "Heraklion" or "Heraclion", but the form "Iraklion" is becoming more common. Knossos is located within the Municipality of Heraklion and has been called as Europe's oldest city. Heraklion is close to the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which in Minoan times was the largest centre of population on Crete. Knossos had a port at the site of Heraklion from the beginning of Early Minoan period (3500 to 2100 BC). Between 1600 and 1525 BC, the port was destroyed by a volcanic tsunami from nearby Santorini, leveling the region and covering it with ash. The present city of Heraklion was founded in 824 by the Arabs under Abu Hafs Umar. They built a moat around the city for protection, and named the city rabḍ al-ḫandaq, "Castle of the Moat", Hellenized as Χάνδαξ, Chandax). It became the capital of the Emirate of Crete (ca. -

Hike Along the Libyan Sea in Crete, Greece May 15 - 26, 2022 $2,850* Per Person Sharing Twin/Bath, $450 Single Supplement

Hiking Adventures Hike along the Libyan Sea in Crete, Greece May 15 - 26, 2022 $2,850* per person sharing twin/bath, $450 single supplement A few years ago, we fell in love with Crete, especially its wild western part. Steep cliffs rise above lonely beaches with crystal clear water, white- washed churches and small villages dot the arid hillsides where the scent of pungent plants perfume the air. This trip offers a chance to spend time in historic Chania, visit the Minoan Palace in Heraklion where the Minotaur once roamed, and, best of all, hike part of the E4 long distance trail along Europe’s southernmost coast facing the Libyan Sea. This is not for the faint of heart as some of the hikes are on exposed, steep trails, and we would rate some of the hikes as strenous. *The tour cost includes all accommodation in twin bedded rooms in hotels and pensions, breakfast and dinner daily, all transfers in Crete, luggage transfers from day 7 - 11, 2 leaders, taxes and service charges. Air transportation to and from Crete is not included. For those who would like to visit Athens before our hike on Crete, an optional program is available (shown in italics). Optional Prelude in Athens: $638 per person sharing twin/bath Thursday, May 12, 2022: Arrive at Athens airport. You are met at the airport and transferred by private car to a centrally located hotel. Friday, May 13, 2022: Full day at leisure to explore Athens. (B) Sunrise Travel ◾ 22891 Via Fabricante Suite 603 ◾ Mission Viejo CA 92691 ◾ CST 1005170-10 ◾ 949.837.0620 ◾ sunriseteam.com GR22itinerary: Updated 4/29/2021EM Saturday, May 14, 2022: in Athens, night ferry to Crete Day at leisure in Athens. -

FOUR-WHEELING GREEK ADVENTURE Exploring the History and Hospitality Found on the Island of Crete by Rental Car

International Travel FOUR-WHEELING GREEK ADVENTURE Exploring the history and hospitality found on the island of Crete by rental car Written and photographs by Katherine Lacksen Mahlberg 24 LAKELIFE MAGAZINE • WINTER 2018 Exploring the Matala caves where a community of backpacking hippies settled in the 1960s in a sleepy fshing village. LAKELIFE MAGAZINE • WINTER 2018 25 VERYTHING I READ ABOUT Crete, Greece, intrigued me – the E rich history, the nAturAl beAuty And the distinct cuisine. While the Greek islAnd of SAntorini tAkes the No. 1 spot on Almost every list of top honeymoon destinAtions, my reseArch in the months leAding up to my wedding led me to believe thAt the is- lAnd of Crete might just offer some of the best kept secrets in the eastern MediterrA- nean. Looking to go somewhere neither of us hAd trAveled to before, my then-fiAncé Nick And I booked our flight And left A week After our wedding to go explore the lArgest islAnd of Greece for ourselves. Due to the mAssive size of the islAnd And its mountAinous, rugged lAndscApe, we rented A mAnuAl, four-wheel drive Suzuki Jimny. The tiny, bright red cAr gAve us the freedom And flexibility – two key require- ments thAt I look for in my trAvels – to visit remote beAches, where Nick completed his scuba diving certificAtion, And the out-of- the-wAy mountAin villAges. After trAversing the mountain roads full of groves of olive trees And herds of sheep, we were Always grAciously wel- comed by our hosts with A fiery shot of rAki. This Cretan brAndy is An integrAl part of locAl culture And is offered As A complimentary welcome or end-of-meal drink.