Pleiotropic Effects of Tocotrienols and Quercetin on Cellular Senescence: Introducing the Perspective of Senolytic Effects of Phytochemicals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Supporting Information for a Microrna Network Regulates

Supporting Information for A microRNA Network Regulates Expression and Biosynthesis of CFTR and CFTR-ΔF508 Shyam Ramachandrana,b, Philip H. Karpc, Peng Jiangc, Lynda S. Ostedgaardc, Amy E. Walza, John T. Fishere, Shaf Keshavjeeh, Kim A. Lennoxi, Ashley M. Jacobii, Scott D. Rosei, Mark A. Behlkei, Michael J. Welshb,c,d,g, Yi Xingb,c,f, Paul B. McCray Jr.a,b,c Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatricsa, Interdisciplinary Program in Geneticsb, Departments of Internal Medicinec, Molecular Physiology and Biophysicsd, Anatomy and Cell Biologye, Biomedical Engineeringf, Howard Hughes Medical Instituteg, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA-52242 Division of Thoracic Surgeryh, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada-M5G 2C4 Integrated DNA Technologiesi, Coralville, IA-52241 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Email: [email protected] (M.J.W.); yi- [email protected] (Y.X.); Email: [email protected] (P.B.M.) This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods References Fig. S1. miR-138 regulates SIN3A in a dose-dependent and site-specific manner. Fig. S2. miR-138 regulates endogenous SIN3A protein expression. Fig. S3. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in Calu-3 cells. Fig. S4. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in primary human airway epithelia. Fig. S5. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HeLa cells. Fig. S6. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HEK293T cells. Fig. S7. HeLa cells exhibit CFTR channel activity. Fig. S8. miR-138 improves CFTR processing. Fig. S9. miR-138 improves CFTR-ΔF508 processing. Fig. S10. SIN3A inhibition yields partial rescue of Cl- transport in CF epithelia. -

BMC Genomics Biomed Central

BMC Genomics BioMed Central Research article Open Access Differential gene expression in femoral bone from red junglefowl and domestic chicken, differing for bone phenotypic traits Carl-Johan Rubin1, Johan Lindberg2, Carolyn Fitzsimmons3, Peter Savolainen2, Per Jensen4, Joakim Lundeberg2, Leif Andersson3,5 and Andreas Kindmark*1 Address: 1Department of Medical Sciences, Uppsala University, Sweden, 2Department of Gene Technology, School of Biotechnology, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 3Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 4IFM Biology, Linköping University, SE-585 83, Linköping, Sweden and 5Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Uppsala University, Box 597, SE-75124 Uppsala, Sweden Email: Carl-Johan Rubin - [email protected]; Johan Lindberg - [email protected]; Carolyn Fitzsimmons - [email protected]; Peter Savolainen - [email protected]; Per Jensen - [email protected]; Joakim Lundeberg - [email protected]; Leif Andersson - [email protected]; Andreas Kindmark* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 2 July 2007 Received: 2 April 2007 Accepted: 2 July 2007 BMC Genomics 2007, 8:208 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-208 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/8/208 © 2007 Rubin et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Osteoporosis is frequently observed among aging hens from egg-producing strains (layers) of domestic chicken. -

“The Impact of ART on Genome‐Wide Oxidation of 5‐Methylcytosine and the Transcriptome During Early Mouse Development”

“The impact of ART on genome‐wide oxidation of 5‐methylcytosine and the transcriptome during early mouse development” Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades “Doktor der Naturwissenschaften” am Fachbereich Biologie der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz Elif Diken geb. Söğütcü geb. am 22.07.1987 in Giresun-TURKEY Mainz 2016 Dekan: 1. Berichterstatter: 2. Berichterstatter: Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: Summary Summary The use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has been increasing over the past three decades due to the elevated frequency of infertility problems. Other factors such as easier access to medical aid than in the past and its coverage by health insurance companies in many developed countries also contributed to this growing interest. Nevertheless, a negative impact of ART on transcriptome and methylation reprogramming is heavily discussed. Methylation reprogramming directly after fertilization manifests itself as genome-wide DNA demethylation associated with the oxidation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) in the pronuclei of mouse zygotes. To investigate the possible impact of ART particularly on this process and the transcriptome in general, pronuclear stage mouse embryos obtained upon spontaneous ovulation or superovulation through hormone stimulation representing ART were subjected to various epigenetic analyses. A whole- transcriptome RNA-Seq analysis of pronuclear stage embryos from spontaneous and superovulated matings demonstrated altered expression of the Bbs12 gene known to be linked to Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS) as well as the Dhx16 gene whose zebrafish ortholog was reported to be a maternal effect gene. Immunofluorescence staining with antibodies against 5mC and 5hmC showed that pronuclear stage embryos obtained by superovulation have an increased incidence of abnormal methylation and hydroxymethylation patterns in both maternal and paternal pronuclear DNA compared to their spontaneously ovulated counterparts. -

Role and Regulation of the P53-Homolog P73 in the Transformation of Normal Human Fibroblasts

Role and regulation of the p53-homolog p73 in the transformation of normal human fibroblasts Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Lars Hofmann aus Aschaffenburg Würzburg 2007 Eingereicht am Mitglieder der Promotionskommission: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Dr. Martin J. Müller Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael P. Schön Gutachter : Prof. Dr. Georg Krohne Tag des Promotionskolloquiums: Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig angefertigt und keine anderen als die angegebenen Hilfsmittel und Quellen verwendet habe. Diese Arbeit wurde weder in gleicher noch in ähnlicher Form in einem anderen Prüfungsverfahren vorgelegt. Ich habe früher, außer den mit dem Zulassungsgesuch urkundlichen Graden, keine weiteren akademischen Grade erworben und zu erwerben gesucht. Würzburg, Lars Hofmann Content SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ IV ZUSAMMENFASSUNG ............................................................................................. V 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Molecular basics of cancer .......................................................................................... 1 1.2. Early research on tumorigenesis ................................................................................. 3 1.3. Developing -

Activation of NF-Κb Signaling Promotes Prostate Cancer Progression in the Mouse and Predicts Poor Progression and Death in Pati

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA: Supplementary Figure 1. NF-B signaling is continuously activated in the prostate of - mouse. In order to determine the NF- '- mouse, we crossed the '- mice with NGL, a NF-B reporter mouse. NGL transgenic mice are engineered to express a GFP/luciferase fusion protein under the control of a promoter containing multiple NF-B consensus binding sites (1). Since the NF-'- NGL mouse is activated in the whole body, the relatively high level of background activation does not allow detection of NF- prostate. Therefore, in order to determine the NF-the '- mouse, we grafted the prostates from 'o the kidney capsule of male nude mice using a tissue rescue technique. NF-B activity was measured at 7 weeks after grafting. The bioluminescence imaging shows NF-B signaling is activated (green) in the kidney, where the grafted prostate from ' use resides (B). In panel (A), the control mouse (grafted with the prostate from NGL mouse) has no bioluminescence, illustrating that in the absence of '-, there is not activation of NF- B. The circles indicate kidney areas. 1 Supplementary Figure 2. NF-B signaling activated in the prostate of Myc/IB bigenic mouse. The prostates from Myc alone (Myc) and bigenic (Myc/IB) mice were harvested at 6 months of age. Activation of NF-B signaling in the prostate was determined by IHC staining of p65-pho antibody. 2 Supplementary Figure 3. Continuous activation of NF-B signaling promotes PCa progression in the Hi-Myc transgenic mouse. The prostates from Myc alone (Myc) and bigeneic (Myc/IB) mice were harvested at 6 months of age. -

Differential Expression of Skin Cancer and Hair-Follicle Cycle Regulated Genes in Tumor Susceptible K14-Agouti Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2006 Differential Expression of Skin Cancer and Hair-Follicle Cycle Regulated Genes in Tumor Susceptible K14-Agouti Mice Yesim Aydin Son University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Life Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Son, Yesim Aydin, "Differential Expression of Skin Cancer and Hair-Follicle Cycle Regulated Genes in Tumor Susceptible K14-Agouti Mice. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2006. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/1636 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yesim Aydin Son entitled "Differential Expression of Skin Cancer and Hair-Follicle Cycle Regulated Genes in Tumor Susceptible K14-Agouti Mice." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Life Sciences. Edward J. Michaud, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Cymbeline T. Culiat, Mitchel -

ID AKI Vs Control Fold Change P Value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In

ID AKI vs control P value Symbol Entrez Gene Name *In case of multiple probesets per gene, one with the highest fold change was selected. Fold Change 208083_s_at 7.88 0.000932 ITGB6 integrin, beta 6 202376_at 6.12 0.000518 SERPINA3 serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (alpha-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 3 1553575_at 5.62 0.0033 MT-ND6 NADH dehydrogenase, subunit 6 (complex I) 212768_s_at 5.50 0.000896 OLFM4 olfactomedin 4 206157_at 5.26 0.00177 PTX3 pentraxin 3, long 212531_at 4.26 0.00405 LCN2 lipocalin 2 215646_s_at 4.13 0.00408 VCAN versican 202018_s_at 4.12 0.0318 LTF lactotransferrin 203021_at 4.05 0.0129 SLPI secretory leukocyte peptidase inhibitor 222486_s_at 4.03 0.000329 ADAMTS1 ADAM metallopeptidase with thrombospondin type 1 motif, 1 1552439_s_at 3.82 0.000714 MEGF11 multiple EGF-like-domains 11 210602_s_at 3.74 0.000408 CDH6 cadherin 6, type 2, K-cadherin (fetal kidney) 229947_at 3.62 0.00843 PI15 peptidase inhibitor 15 204006_s_at 3.39 0.00241 FCGR3A Fc fragment of IgG, low affinity IIIa, receptor (CD16a) 202238_s_at 3.29 0.00492 NNMT nicotinamide N-methyltransferase 202917_s_at 3.20 0.00369 S100A8 S100 calcium binding protein A8 215223_s_at 3.17 0.000516 SOD2 superoxide dismutase 2, mitochondrial 204627_s_at 3.04 0.00619 ITGB3 integrin, beta 3 (platelet glycoprotein IIIa, antigen CD61) 223217_s_at 2.99 0.00397 NFKBIZ nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor, zeta 231067_s_at 2.97 0.00681 AKAP12 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 12 224917_at 2.94 0.00256 VMP1/ mir-21likely ortholog -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,057,109 B2 Chang (45) Date of Patent: Jun

US009057109B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9,057,109 B2 Chang (45) Date of Patent: Jun. 16, 2015 (54) DIAGNOSIS OF MELANOMA AND SOLAR 5,989,815 A 11/1999 Skolnicket al. LENTIGO BY NUCLEC ACID ANALYSIS 6,054,277 A 4/2000 Furcht et al. 6,056,859 A 5/2000 Ramsey et al. 6,129,983 A 10/2000 Schumann et al. (71) Applicant: DermTech International, La Jolla, CA 6,203,987 B1 3/2001 Friend et al. (US) 6,312.909 B1 1 1/2001 Shyjan 6,355.439 B1 3/2002 Chung et al. (72) Inventor: Sherman H. Chang, San Diego, CA 6.410,019 B1 6/2002 DeSimone et al. 6,410,240 B1 6/2002 Hodge et al. (US) 6,551,799 B2 4/2003 Gurney et al. 6,720,145 B2 4/2004 Rheins et al. (73) Assignee: DERMTECH INTERNATIONAL, La 6,726,971 B1 4/2004 Wong Jolla, CA (US) 6,891,022 B1 5/2005 Steward et al. 6,949,338 B2 9, 2005 Rheins et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 7,183,057 B2 2/2007 Benson 7,247.426 B2 7/2007 Yakhini et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 7,267,951 B2 9, 2007 Alani et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 7,297,480 B2 11/2007 Vogt 7,615,349 B2 11/2009 Riker et al. (21) Appl. No.: 14/199,900 7,662,558 B2 2/2010 Liew 7.919,246 B2 * 4/2011 Lai et al. -

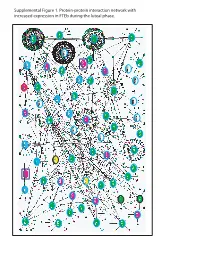

Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-Protein Interaction Network with Increased Expression in Fteb During the Luteal Phase

Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-protein interaction network with increased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Supplemental Figure 2. Protein-protein interaction network with decreased expression in FTEb during luteal phase. LEGENDS TO SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES Supplemental Figure 1. Protein-protein interaction network with increased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Submission of probe sets differentially expressed in the FTEb specimens that clustered with SerCa as well as those specifically altered in FTEb luteal samples to the online I2D database revealed overlapping networks of proteins with increased expression in the four FTEb samples and/or FTEb luteal samples overall. Proteins are represented by nodes, and known and predicted first-degree interactions are represented by solid lines. Genes encoding proteins shown as large ovals highlighted in blue were exclusively found in the first comparison (Manuscript Figure 2), whereas those highlighted in red were only found in the second comparison (Manuscript Figure 3). Genes encoding proteins shown as large ovals highlighted in black were found in both comparisons. The color of each node indicates the ontology of the corresponding protein as determined by the Online Predicted Human Interaction Database (OPHID) link with the NAViGaTOR software. Supplemental Figure 2. Protein-protein interaction network with decreased expression in FTEb during the luteal phase. Submission of probe sets differentially expressed in the FTEb specimens that clustered with SerCa as well as those specifically altered in FTEb luteal samples to the online I2D database revealed overlapping networks of proteins with decreased expression in the four FTEb samples and/or FTEb luteal samples overall. Proteins are represented by nodes, and known and predicted first-degree interactions are represented by solid lines. -

Details About Three Fatty Acid Oxidation Pathways Occurring in Man

Supplement information Details about three fatty acid oxidation pathways occurring in man Alpha oxidation Definition: Oxidation of the alpha carbon of the fatty acid, chain shortened by 1 carbon atom. Localization: Peroxisomes1 Substrates: Phytanic acid, 3-methyl fatty acids and their alcohol and aldehyde derivatives, metabolites of farnesol, geranylgeraniol, and dolichols2, 3. Steps in the pathway: Activation requires ATP and CoA. Hydroxylation requires iron, ascorbate and alpha-keto-glutarate as cofactors and secondary substrates. Lysis requires thymine pyrophosphate and magnesium ions. Dehydrogenation requires NADP. End products are transported into mitochondria for further oxidation. Enzymes and genes involved: Very long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (E.C. 6.2.1.-) (SLC27A2, GeneID: 11001)4, phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase (E.C. 1.14.11.18, PHYH, GeneID: 5264), 2-hydrosyphytanoyl-coA lyase (E.C. 4.1.-.-, HACL1, GeneID: 26061), and aldehyde dehydrogenase (E.C. 1.2.1.3, ALDH3A2, GeneID: 224). Disorders associated: Zellweger syndrome including RCDP type 1, where PTS2 receptor is defective and PHYH is unable to enter peroxisomes, and Refsum’s disease. Special features/ purpose: At the sub cellular level, the activation step can occur in the mitochondrion, endoplasmic reticulum, and peroxisome. Formic acid is the main byproduct of this pathway as opposed to carbon dioxide. Phytanic acid usually undergoes alpha oxidation; however, under conditions of enzyme deficiency, it undergoes omega oxidation and 3- methyladipic acid is produced as the end product5. Omega oxidation Definition: Oxidation of omega carbon of the fatty acid for generation of mono- and di- carboxylic acids. No chain shortening occurs. Localization: Fatty acid shuttles between cytosol and microsomes before entering the peroxisomes6. -

Transcriptomic Approaches to Study the Effects of Xenobiotics in Ruminants

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA Dipartimento di BIOMEDICINA COMPARATA E ALIMENTAZIONE Corso di dottorato di ricerca in SCIENZE VETERINARIE Ciclo XXIX TRANSCRIPTOMIC APPROACHES TO STUDY THE EFFECTS OF XENOBIOTICS IN RUMINANTS Tesi redatta con il contributo finanziario della Commissione Europea – Programma europeo ERASMUS MUNDUS Action 2 (AL FIHRI) Coordinatore: Ch.mo Prof. (Alessandro ZOTTI) Supervisore: Ch.mo Prof. (Mauro DACASTO) Dottorando: RAMY ELGENDY 2017 To my parents, sister and brother.. Even if you don’t fully understand what I am doing, and probably won’t read this thesis ever, Thank you for being always proud of me. شكر ًا لكل ما فعلتموه من أجلي To all the obstacles and hardships.. You have made me stronger Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor – and friend – Prof. Mauro Dacasto for the continuous support of my PhD study and related research, for his guidance and motivation. His encouragement and oppeness allowed me to grow both scientifically and professionally. I couldn’t have imagined having a better advisor. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank Dr. Mery Giantin who taught me many things from the scratch. Without her knowledge and precious support it would not be possible to conduct this research. She has been a caring and supportive big sister to me. I would also like to thank both Prof. Juan Loor and Dr. Massimo Bionaz for acting as external evaluators of my thesis and for providing me with valuable comments and observations. This thesis represents not only my work in the lab or at the computer’s keyboard, it is a collective representation of more than three years of team work at the Pharmacogenetics and Toxicogenomics laboratory of Prof Dacasto. -

European Journal of Immunology

European Journal of Immunology Supporting Information for Eur. J. Immunol. 10.1002/eji.200838136 Features of TAP-independent MHC class I ligands revealed by quantitative mass spectrometry Andreas O. Weinzierl, Despina Rudolf, Nina Hillen, Stefan Tenzer, Peter van Endert, Hansjörg Schild, Hans-Georg Rammensee and Stefan Stevanović © 2008 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.eji-journal.eu Supplementary tables Supplementary table 1 A quantitative analysis of protein and mRNA levels demonstrates partial deletion of chromosome 6p21.3. The analysis comprised constitutive proteasomal subunits (PSMB1, 2 and 5), immunoproteasomal subunits (LMP7, 2 and MECL1), subunits of the immunoproteasomal regulator PA28 (PSME1-3), proteins of the HLA peptide loading complex (TAP1 and 2, tapasin, calreticulin, calnexin and PDIA3), HLA class I and II (HLA-A, -B, -C, - DR, -DP and -DQ), the endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase associated with antigen processing (ERAAP) and proteins of the SEC61 translocon which can be involved in peptide export from the ER. Genes encoded in the deleted region of chromosome 6p21.3 in LCL721.174 cells are highlighted in bold. Gene 2log (LCL721.174 vs. LCL721.45) Gene Title Symbol protein mRNA PSMB1 proteasome subunit beta 1 -0.29 n.d. PSMB2 proteasome subunit beta 2 -0.54 n.d. PSMB5 proteasome subunit beta 3 LCL721.174 only 0.2 LMP7 proteasome subunit beta 8 721.45 only 721.45 only LMP2 proteasome subunit beta 9 721.45 only 721.45 only MECL1 proteasome subunit beta 10 721.45 only -1.4 PSME1 proteasome activator subunit 1 -0.82 -0.7 PSME2 proteasome activator subunit 2 -0.56 0.3 PSME3 proteasome activator subunit 3 721.45 only 0.9 CALR calreticulin n.a.