'It Is Time We Went out to Meet Them': Empathy and Historical Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

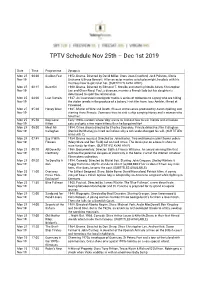

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Fred Tomlin (Boom Operator) 1908 - ? by Admin — Last Modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM

Fred Tomlin (boom operator) 1908 - ? by admin — last modified Jul 27, 2008 02:45 PM BIOGRAPHY: Fred Tomlin was born in 1908 in Hoxton, London, just around the corner from what became the Gainsborough Film Studios (Islington) in Poole Street. He first visited the studio as a child during the filming of Woman to Woman (1923). He entered the film industry as an electrician, working in a variety of studios including Wembley, Cricklewood and Islington. At Shepherd’s Bush studio he got his first experience as a boom operator, on I Was A Spy (1933). Tomlin claims that from that point until his retirement he was never out of work, but also that he was never under permanent contract to any studio, working instead on a freelance basis. During the 1930s he worked largely for Gaumont and Gainsborough on films such as The Constant Nymph (1933), Jew Suss (1934), My Old Dutch (1934), and on the Will Hay comedies, including Oh, Mr Porter (1937) and Windbag the Sailor (1936). During the war, Tomlin served in the army, and on his return continued to work as a boom operator on films and television (often alongside Leslie Hammond) until the mid 1970s. His credits include several films for Joseph Losey (on Boom (1968) and Secret Ceremony (1968)) and The Sea Gull (1968)for Sidney Lumet, as well as TV series such as Robin Hood and The Buccaneers and a documentary made in Cuba for Granada TV. SUMMARY: In this interview from 1990, Tomlin talks to Bob Allen about his career, concentrating mainly on the pre-war period. -

Film Noir Database

www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) Film Noir Database This database has been created by author, P.S. Marshall, who has watched every single one of the movies below. The latest update of the database will be available on my website: www.kingofthepeds.com The following abbreviations are added after the titles and year of some movies: AFN – Alternative/Associated to/Noirish Film Noir BFN – British Film Noir COL – Film Noir in colour FFN – French Film Noir NN – Neo Noir PFN – Polish Film Noir www.kingofthepeds.com © P.S. Marshall (2021) TITLE DIRECTOR Actor 1 Actor 2 Actor 3 Actor 4 13 East Street (1952) AFN ROBERT S. BAKER Patrick Holt, Sandra Dorne Sonia Holm Robert Ayres 13 Rue Madeleine (1947) HENRY HATHAWAY James Cagney Annabella Richard Conte Frank Latimore 36 Hours (1953) BFN MONTGOMERY TULLY Dan Duryea Elsie Albiin Gudrun Ure Eric Pohlmann 5 Against the House (1955) PHIL KARLSON Guy Madison Kim Novak Brian Keith Alvy Moore 5 Steps to Danger (1957) HENRY S. KESLER Ruth Ronan Sterling Hayden Werner Kemperer Richard Gaines 711 Ocean Drive (1950) JOSEPH M. NEWMAN Edmond O'Brien Joanne Dru Otto Kruger Barry Kelley 99 River Street (1953) PHIL KARLSON John Payne Evelyn Keyes Brad Dexter Frank Faylen A Blueprint for Murder (1953) ANDREW L. STONE Joseph Cotten Jean Peters Gary Merrill Catherine McLeod A Bullet for Joey (1955) LEWIS ALLEN Edward G. Robinson George Raft Audrey Totter George Dolenz A Bullet is Waiting (1954) COL JOHN FARROW Rory Calhoun Jean Simmons Stephen McNally Brian Aherne A Cry in the Night (1956) FRANK TUTTLE Edmond O'Brien Brian Donlevy Natalie Wood Raymond Burr A Dangerous Profession (1949) TED TETZLAFF George Raft Ella Raines Pat O'Brien Bill Williams A Double Life (1947) GEORGE CUKOR Ronald Colman Edmond O'Brien Signe Hasso Shelley Winters A Kiss Before Dying (1956) COL GERD OSWALD Robert Wagner Jeffrey Hunter Virginia Leith Joanne Woodward A Lady Without Passport (1950) JOSEPH H. -

Notes and References

Notes and References CHAPTER 1 To provide an intellectual and cultural framework for examining Carol Reed's films, a history of the British cinema from its origins through to the Second World War is offered in this chapter. Although Reed began directing in 1935, 1939 seemed a tidier, more logical cut-off point for the survey. All the information in the chapter is synthesized from several excellent works on the subject: Roy Armes's A Critical History of the British Cinema, Ernest Betts' The Film Business, Ivan Butler's Cinema in Britain, Denis Gifford's British Film Catalogue, Rachel Low's History of the British Film, and George Perry's The Great British Picture Show. CHAPTER 2 1. Michael Korda, Charmed Lives (New York, 1979) p. 229; Madeleine Bingham, The Great Lover (London, 1978). 2. Frances Donaldson, The Actor-Managers (London, 1970) p. 165. 3. Interview with the author. Unless otherwise identified, all quota tions in this study from Max Reed, Michael Korda and Andrew Birkin derive from interviews. 4. C. A. Lejeune, 'Portrait of England's No.1 Director', New York Times, 7 September 1941, p. 3. 5. Harvey Breit, ' "I Give the Public What I Like" " New York Times Magazine, 15January 1950, pp. 18-19. 6. Korda, Charmed Lives, p. 244. 7. Kevin Thomas, 'Director of "Eagle" Stays Unflappable', The Los Angeles Times, 24 August 1969. CHAPTER 3 1. Michael Voigt, 'Pictures of Innocence: Sir Carol Reed', Focus on Film, no. 17 (Spring 1974) 34. 2. 'Midshipman Easy', The Times, 23 December 1935. 271 272 Notes and References 3. -

TPTV Schedule Sept 23Rd– Sept 29Th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 23 06:00 Music Hall 1934

TPTV Schedule Sept 23rd– Sept 29th 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 23 06:00 Music Hall 1934. Musical. Director: John Baxter. Stars George Carney, Ben Field, Mark Daly Sep 19 & Helena Pickard. A rare film put out by Twickenham Film Studios which includes many original music hall acts. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 23 07:20 Windbag The Sailor 1936. Comedy. Directed by William Beaudine. Stars Will Hay, Moore Marriott, Sep 19 Graham Moffatt & Norma Varden. A sea captain's tall tales are tested when he is coerced into commanding an unseaworthy ship. Mon 23 09:00 Challenge For Robin 1967. Adventure. Director C.M Pennington Richards. Stars Barrie Ingham, James Sep 19 Hood Hayter & Leon Greene. Robin de Courtenay, a Norman noble, is framed by his cousin for murder and so he flees to Nottingham Mon 23 11:00 Stagecoach West High Lonesome. Western with Wayne Rogers & Robert Bray, who run a Sep 19 stagecoach line in the Old West where they come across a wide variety of killers, robbers and ladies in distress. Mon 23 12:00 The Big Job 1965. Comedy. A gang of crooks are caught on a big job. 15 years later they find Sep 19 their loot is now buried under a police station. Stars Sidney James, Sylvia Syms, Dick Emery & Joan Sims. Mon 23 13:45 The Grayson Case In the style of early Edgar Lustgarten, Crime Cameo, The Grayson Case narrated Sep 19 by J. St John Barry, proves how married Sally Turner's affair with the painter Edwin Grayson led to murder. -

CRITERION COLLECTION PRESENTS the Forgiveness of Blood

AVAILABLE on BLU-RAY AnD DVD! THE CRITERION COLLECTION PRESENTS ThE FoRgIVEnEss oF BLooD THE STARTLING NEW DRAMA FROM THE DIRECTOR OF MARIA FULL OF GRACE FRESH FROm its THEaTRICaL RuN! american director JOSHUA MARSTON broke out in 2004 with his jolting, Oscar-nominated Maria Full of Grace, about a young Colombian woman working as a drug mule. In his remarkable follow-up, The Forgiveness of Blood, he turns his camera on another corner of the world: contemporary northern albania, a place still troubled by the ancient custom of interfamilial blood feuds. From this reality, marston sculpts a fictional narrative about a teenage brother and sister physically and emotionally trapped in a cycle of violence, a result of their father’s entanglement with a rival clan over a piece of land. The Forgiveness of Blood is a tense and perceptive depiction of a place where tradition and progress have an uneasy coexistence, as well as a dynamic coming-of-age drama. WINNER DIRECTOR-APPROVED Best SCREENPLay, BERLIN FILm FestivaL, 2011 SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES · New high-definition digital transfer, approved by producer Paul mezey, with 5.1 surround DTS-HD “Marston may be indie cinema’s finest master audio soundtrack on the Blu-ray edition immersive journalist.” · Audio commentary featuring director and cowriter —David Fear, Time Out New York Joshua marston · Two new video programs: Acting Close to Home, “An accomplished and suspenseful drama.” a discussion between marston and actors Refet —The Hollywood Reporter abazi, Tristan Halilaj, and Sindi Laçej, and Truth on the Ground, featuring new and on-set interviews with mezey, abazi, Halilaj, and Laçej BLU-RAY EDITION SRP $39.95 PREBOOk 9/18/12 STREET 10/16/12 · audition and rehearsal footage CaT. -

Week Beginning Monday 1St October 2018

Highlights: Week beginning Monday 1st October 2018 st Monday 1 October 2018 – 13:55 THE LAST MAN TO HANG (1956) Director: Terence Fisher Starring: Tom Conway, Elizabeth Sellars, Eunice Gayson and Anthony Newley. Sir Roderick Strood is on trial for the murder of his sick wife, by means of a sedative overdose. But was it accidental or deliberate? st Monday 1 October 2018 – 21:00 th THE SWIMMER (1968) (also showing Sunday 7 October at 22:10) Director: Frank Perry and Sydney Pollack Starring: Burt Lancaster, Janet Landgard, Janice Rule and Marge Champion. When visiting a friend, Ned notices the abundance of swimming pools that populate the Suburbs back gardens and decides he will swim each one on his 8 mile trip home. nd Tuesday 2 October 2018 – 15:15 INTERLUDE (1968) Director: Kevin Billington Starring: Oskar Werner, Barbara Ferris, Virginia Maskell and Donald Sutherland. A famous conductor gives an interview to a pretty young reporter. He speaks a bit too frankly and soon begins an affair with the journalist, despite being married. nd Tuesday 2 October 2018 – 21:00 CONSPIRACY OF HEARTS (1960) Director: Ralph Thomas Starring: Lilli Palmer, Sylvia Syms, Yvonne Mitchell and Ronald Lewis. During World War II, Mother Superior Katharine oversees a picturesque Italian convent and makes it her duty to smuggle out the Jewish children from a concentration camp. nd Tuesday 2 October 2018 – 23:10 th SEE NO EVIL (1971) (also showing Saturday 6 October at 21:00) Director: Richard Fleischer Starring: Mia Farrow, Dorothy Alison, Robin Bailey and Diane Grayson In the English countryside, Sarah, recently blinded in a horse riding accident, moves in with her uncle's family and adjusts to her new condition, unaware that a killer stalks them. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 APRIL/MAY 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 APRIL/MAY 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping you are all well and safe, can you believe it, Talking Pictures TV is six in just a few weeks time! It doesn’t quite seem possible and with 6 million of you watching every week it does seem like Noel was right! The Saturday Morning Pictures ‘revival’ has been a real hit with you all and there’s lots more planned for our regular Saturday slot 9-12. Radar Men from the Moon and The Cisco Kid start on Saturday 1st May. GOOD NEWS! We have created a beautiful limited edition enamel badge for all you Saturday Morning Pictures TPTV is 6! club members, see page 7 for details. This month sees the release of two new box sets from Renown Pictures. Our very popular Glimpses collections continue with GLIMPSES VOLUME 5. Some real treats on the three discs, including fascinating footage of Manchester in the 60s, London in the 70s, a short film on greyhound racing in the 70s, The Hillman Minx and Sheffield in the 50s. Still just £20 with free UK postage! Also this month on DVD, fully restored with optional subtitles, you can all recreate Saturday Morning Pictures anytime you like with your own DVD set of FLASH GORDON CONQUERS THE UNIVERSE – just £15 with free UK postage. We’re delighted to announce that LOOK AT LIFE is finally in its rightful home on TPTV, starting in May. -

Humorbritkomedie Copy

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Teologická fakulta Katedra pedagogiky Diplomová práce HUMOR V BRITSKÝCH ZVUKOVÝCH KOMEDIÍCH V POROVNÁNÍ S NĚKTERÝMI ČESKÝMI FILMOVÝMI PŘÍKLADY Vedoucí práce: Prof. Dr. Gabriel Švejda, CSc. Autor práce: Bc. Gabriela Mádlo, Dis. Studijní obor: Pastorační a sociální asistent Ročník: IX. 2010 1 Prohlašuji, že svoji diplomovou práci jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s par. 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění, souhlasím se zveřejněním své diplomové práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách 21. března 2010 vlastnoruční podpis autora diplomové práce 2 Děkuji vedoucímu diplomové práce prof. Dr. Gabrielu Švejdovi, CSc. a konzultantovi Mgr. Borisi Jachninovi za cenné rady, připomínky a metodické vedení práce. 3 Obsah Úvod 6 1. Co je to komedie? 8 1.1 Filmová komedie 10 1.2 Struktura komediálního příběhu 13 a) Protasis 13 b) Epitasis 16 c) Catastasis 16 d) Catastrophe 18 2. Situace kinematografie nejen v Anglii ve 30. až 50. letech 20.století 20 2.1 Gainsborough Pictures a Gaumont-British Pictures Corporation 25 2.1.1 Jack Hulbert a jeho tvorba 26 2.1.2 Frašky z divadla Aldwych na plátně 27 2.1.3 Will Hay 29 2.1.4 Crazy Gang 34 2.1.5 Tommy Handley 38 2.1.6 Arthur Askey 40 2.1.7 Jessie Matthews 40 2.2 Ealing Studios 41 2.2.1 Will Hay v Ealing Studiích 41 2.2.2 Gracie Fields 43 2.2.3 George Formby 44 2.2.4 Ostatní produkce 45 2.3 Rank Organisation 46 2.4 Česká scéna 47 2.4.1 Lamač - Ondráková - Wasserman - Heller 48 2.4.2 Vlasta Burian - Jarosla Marvan - Čeněk Šlégl 49 3. -

Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction

Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction EthicsCanada and in the FrameAesthetics ofGeorgetteCopyright, Translation Collections Heyer, and Historythe Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 Exploringand Historical the Work of Atxaga, Fiction Kundera and Semprún Edited by Samantha J. Rayner and Kim Wilkins HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2021 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.uclpress.co.uk Collection © Editors, 2021 Text © Contributors, 2021 Images © Contributors and copyright holders named in captions, 2021 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Derivative 4.0 International licence (CC BY-ND 4.0). This licence allows you to share, copy and redistribute the work providing attribution is made to the author and publisher (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work) and any changes are indicated. If you remix, transform or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modified material. Attribution should include the following information: Rayner, S. J. and Wilkins, K. (eds). 2021. Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction. London: UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787357600 Further details about Creative Commons licences are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons licence unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material.