British National Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research Through a History of Aardman Animations

Aardman in Archive Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive | Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Rebecca Adrian Aardman in Archive: Exploring Digital Archival Research through a History of Aardman Animations Copyright © 2018 by Rebecca Adrian All rights reserved. Cover image: BTS19_rgb - TM &2005 DreamWorks Animation SKG and TM Aardman Animations Ltd. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Media and Performance Studies at Utrecht University. Author Rebecca A. E. E. Adrian Student number 4117379 Thesis supervisor Judith Keilbach Second reader Frank Kessler Date 17 August 2018 Contents Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii Introduction 1 1 // Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.1 | Lack of Histories of Stop-Motion Animation and Aardman 4 1.2 | Marketing, Glocalisation and the Success of Aardman 7 1.3 | The Influence of the British Television Landscape 10 2 // Digital Archival Research 12 2.1 | Digital Surrogates in Archival Research 12 2.2 | Authenticity versus Accessibility 13 2.3 | Expanded Excavation and Search Limitations 14 2.4 | Prestige of Substance or Form 14 2.5 | Critical Engagement 15 3 // A History of Aardman in the British Television Landscape 18 3.1 | Aardman’s Origins and Children’s TV in the 1970s 18 3.1.1 | A Changing Attitude towards Television 19 3.2 | Animated Shorts and Channel 4 in the 1980s 20 3.2.1 | Broadcasting Act 1980 20 3.2.2 | Aardman and Channel -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

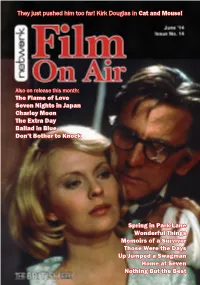

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

![LOST for NEARLY a CENTURY LOVE, LIFE and LAUGHTER SCREENS AS BFI LFF’S ARCHIVE SPECIAL PRESENTATION with LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT [3Rd OCTOBER, BFI SOUTHBANK]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3386/lost-for-nearly-a-century-love-life-and-laughter-screens-as-bfi-lff-s-archive-special-presentation-with-live-musical-accompaniment-3rd-october-bfi-southbank-403386.webp)

LOST for NEARLY a CENTURY LOVE, LIFE and LAUGHTER SCREENS AS BFI LFF’S ARCHIVE SPECIAL PRESENTATION with LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT [3Rd OCTOBER, BFI SOUTHBANK]

LOST FOR NEARLY A CENTURY LOVE, LIFE AND LAUGHTER SCREENS AS BFI LFF’S ARCHIVE SPECIAL PRESENTATION WITH LIVE MUSICAL ACCOMPANIMENT rd [3 OCTOBER, BFI SOUTHBANK] Tuesday 27 August, 10:30am London – The 63rd BFI London Film Festival in partnership with American Express is thrilled to announce George Pearson’s LOVE, LIFE AND LAUGHTER (1923) as this year’s Archive Special Presentation. Lost for nearly a century, this film was on the BFI 75 Most Wanted list and one of its most sought after titles for decades and has now been carefully restored by the team at the BFI National Archive. Its screening at this year’s Festival gives audiences the chance to fall under the spell of Betty Balfour, Britain’s ‘Queen of Happiness’ and the nation’s biggest star of the 1920s. The presentation will take place at BFI Southbank on Thursday 3rd October, 6.10pm in NFT1 with a live musical accompaniment by Meg Morley as well as an extended introduction by the BFI National Archive’s Silent Curator Bryony Dixon and the BFI’s Film Conservation Manager Kieron Webb. LOVE, LIFE AND LAUGHTER tells the story of a pair of working class youngsters with big dreams – a cheery chorus girl and a serious writer – the film toys with our expectations, blurring the boundaries of reverie and reality, tragedy and comedy. The films aesthetic is extremely evocative of the period, full of Art Deco styling from the overall design to Balfour’s costumes and the film’s set pieces. This restoration is a major event enabling today’s audiences to enjoy a truly vivacious performance from Balfour in one of her key films and adds to our knowledge of director Pearson, often likened to Dickens (whom he admired) for his ability to wring the maximum amount of emotion out of a story and a key figure in British cinema with now only a bare handful of his films survive. -

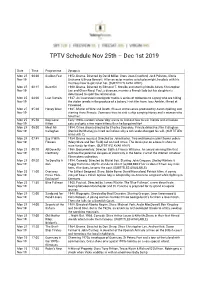

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

The Secret Scripture

Presents THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Directed by JIM SHERIDAN/ In cinemas 7 December 2017 Starring ROONEY MARA, VANESSA REDGRAVE, JACK REYNOR, THEO JAMES and ERIC BANA PUBLICITY REQUESTS: Transmission Films / Amy Burgess / +61 2 8333 9000 / [email protected] IMAGES High res images and poster available to download via the DOWNLOAD MEDIA tab at: http://www.transmissionfilms.com.au/films/the-secret-scripture Distributed in Australia by Transmission Films Ingenious Senior Film Fund Voltage Pictures and Ferndale Films present with the participation of Bord Scannán na hÉireann/ the Irish Film Board A Noel Pearson production A Jim Sheridan film Rooney Mara Vanessa Redgrave Jack Reynor Theo James and Eric Bana THE SECRET SCRIPTURE Six-time Academy Award© nominee and acclaimed writer-director Jim Sheridan returns to Irish themes and settings with The Secret Scripture, a feature film based on Sebastian Barry’s Man Booker Prize-winning novel and featuring a stellar international cast featuring Rooney Mara, Vanessa Redgrave, Jack Reynor, Theo James and Eric Bana. Centering on the reminiscences of Rose McNulty, a woman who has spent over fifty years in state institutions, The Secret Scripture is a deeply moving story of love lost and redeemed, against the backdrop of an emerging Irish state in which female sexuality and independence unsettles the colluding patriarchies of church and nationalist politics. Demonstrating Sheridan’s trademark skill with actors, his profound sense of story, and depth of feeling for Irish social history, The Secret Scripture marks a return to personal themes for the writer-director as well as a reunion with producer Noel Pearson, almost a quarter of a century after their breakout success with My Left Foot. -

Finding Neverland

BARRIE AND THE BOYS 0. BARRIE AND THE BOYS - Story Preface 1. J.M. BARRIE - EARLY LIFE 2. MARY ANSELL BARRIE 3. SYLVIA LLEWELYN DAVIES 4. PETER PAN IS BORN 5. OPENING NIGHT 6. TRAGEDY STRIKES 7. BARRIE AND THE BOYS 8. CHARLES FROHMAN 9. SCENES FROM LIFE 10. THE REST OF THE STORY Barrie and the Llewelyn-Davies boys visited Scourie Lodge, Sutherland—in northwestern Scotland—during August of 1911. In this group image we see Barrie with four of the boys together with their hostess. In the back row: George Llewelyn Davies (age 18), the Duchess of Sutherland and Peter Llewelyn Davies (age 14). In the front row: Nico Llewelyn Davies (age 7), J. M. Barrie (age 51) and Michael Llewelyn Davies (age 11). Online via Andrew Birkin and his J.M. Barrie website. After their mother's death, the five Llewelyn-Davies boys were alone. Who would take them in? Be a parent to them? Provide for their financial needs? Neither side of the family was really able to help. In 1976, Nico recalled the relief with which his uncles and aunts greeted Barrie's offer of assistance: ...none of them [the children's uncles and aunts] could really do anything approaching the amount that this little Scots wizard could do round the corner. He'd got more money than any of us and he's an awfully nice little man. He's a kind man. They all liked him a good deal. And he quite clearly had adored both my father and mother and was very fond of us boys. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994.