From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama in John Osborne's

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (September. 2018) 77-80 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Influence of Kitchen Sink Drama In John Osborne’s “ Look Back In Anger” Sadaf Zaman Lecturer University of Bisha Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Corresponding Author: Sadaf Zaman ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission:16-09-2018 Date of acceptance: 01-10-2018 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------- John Osborne was born in London, England in 1929 to Thomas Osborne, an advertisement writer, and Nellie Beatrice, a working class barmaid. His father died in 1941. Osborne used the proceeds from a life insurance settlement to send himself to Belmont College, a private boarding school. Osborne was expelled after only a few years for attacking the headmaster. He received a certificate of completion for his upper school work, but never attended a college or university. After returning home, Osborne worked several odd jobs before he found a niche in the theater. He began working with Anthony Creighton's provincial touring company where he was a stage hand, actor, and writer. Osborne co-wrote two plays -- The Devil Inside Him and Personal Enemy -- before writing and submittingLook Back in Anger for production. The play, written in a short period of only a few weeks, was summarily rejected by the agents and production companies to whom Osborne first submitted the play. It was eventually picked up by George Devine for production with his failing Royal Court Theater. Both Osborne and the Royal Court Theater were struggling to survive financially and both saw the production of Look Back in Anger as a risk. -

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs

A Framework for the Static and Dynamic Analysis of Interaction Graphs DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sitaram Asur, B.E., M.Sc. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Prof. Srinivasan Parthasarathy, Adviser Prof. Gagan Agrawal Adviser Prof. P. Sadayappan Graduate Program in Computer Science and Engineering c Copyright by Sitaram Asur 2009 ABSTRACT Data originating from many different real-world domains can be represented mean- ingfully as interaction networks. Examples abound, ranging from gene expression networks to social networks, and from the World Wide Web to protein-protein inter- action networks. The study of these complex networks can result in the discovery of meaningful patterns and can potentially afford insight into the structure, properties and behavior of these networks. Hence, there is a need to design suitable algorithms to extract or infer meaningful information from these networks. However, the challenges involved are daunting. First, most of these real-world networks have specific topological constraints that make the task of extracting useful patterns using traditional data mining techniques difficult. Additionally, these networks can be noisy (containing unreliable interac- tions), which makes the process of knowledge discovery difficult. Second, these net- works are usually dynamic in nature. Identifying the portions of the network that are changing, characterizing and modeling the evolution, and inferring or predict- ing future trends are critical challenges that need to be addressed in the context of understanding the evolutionary behavior of such networks. To address these challenges, we propose a framework of algorithms designed to detect, analyze and reason about the structure, behavior and evolution of real-world interaction networks. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

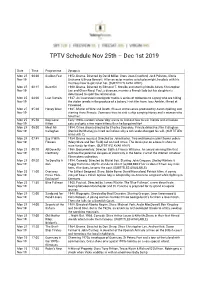

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper -

SPIES, REAL and IMAGINED Coordinators: Lucy Kirk, Rena

SPIES, REAL AND IMAGINED Coordinators: Lucy Kirk, Rena Shagan, and Maureen Sullivan "I've got a story to tell you . about spies," says Ricki Tarr in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Stories about spies raise many issues - morality, patriotism, recruiting, betrayal, conspiracy. They also tell us what motivates people to become spies - love of danger, ideology, money, blackmail . We investigate the matrix of issues and motivation through five books, both fiction and non-fiction, concentrating on the Cold War. We discuss the intelligence organizations, their spycraft, and the believability of the characters. Background material includes the history of the Cold War, its participants and events. Some of the best spy fiction is written by former case officers. Coordinator Lucy Kirk shares her experience constructing her own spy novel, including what a career officer can disclose about operations and how to fictionalize former colleagues. Readings: NOTE: Low cost used books are available from BookFinder.com. Any edition can be purchased. Please read entire book prior to first week's discussion of that book. 1. Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy by John le Carré, {1974} FICTION: George Smiley, le Carré's continuing character, searches for a mole in Britain's Secret Intelligence Service, MI6. This is le Carré's most famous Smiley book. 2. The Main Enemy by Milton Beardon and James Risen, {2003} NONFICTION: The inside story of the CIA's final showdown with the KGB 3. Istanbul Passage by Joseph Kanon, {2012} FICTION: Formerly neutral city must take sides at the outbreak of the Cold War. 4. The Geneva Trap by Stella Rimington, {2012} FICTION: Cyber sabotage threatens West defenses. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. BA Bryan Adams=Canadian rock singer- Brenda Asnicar=actress, singer, model=423,028=7 songwriter=153,646=15 Bea Arthur=actress, singer, comedian=21,158=184 Ben Adams=English singer, songwriter and record Brett Anderson=English, Singer=12,648=252 producer=16,628=165 Beverly Aadland=Actress=26,900=156 Burgess Abernethy=Australian, Actor=14,765=183 Beverly Adams=Actress, author=10,564=288 Ben Affleck=American Actor=166,331=13 Brooke Adams=Actress=48,747=96 Bill Anderson=Scottish sportsman=23,681=118 Birce Akalay=Turkish, Actress=11,088=273 Brian Austin+Green=Actor=92,942=27 Bea Alonzo=Filipino, Actress=40,943=114 COMPLETEandLEFT Barbara Alyn+Woods=American actress=9,984=297 BA,Beatrice Arthur Barbara Anderson=American, Actress=12,184=256 BA,Ben Affleck Brittany Andrews=American pornographic BA,Benedict Arnold actress=19,914=190 BA,Benny Andersson Black Angelica=Romanian, Pornstar=26,304=161 BA,Bibi Andersson Bia Anthony=Brazilian=29,126=150 BA,Billie Joe Armstrong Bess Armstrong=American, Actress=10,818=284 BA,Brooks Atkinson Breanne Ashley=American, Model=10,862=282 BA,Bryan Adams Brittany Ashton+Holmes=American actress=71,996=63 BA,Bud Abbott ………. BA,Buzz Aldrin Boyce Avenue Blaqk Audio Brother Ali Bud ,Abbott ,Actor ,Half of Abbott and Costello Bob ,Abernethy ,Journalist ,Former NBC News correspondent Bella ,Abzug ,Politician ,Feminist and former Congresswoman Bruce ,Ackerman ,Scholar ,We the People Babe ,Adams ,Baseball ,Pitcher, Pittsburgh Pirates Brock ,Adams ,Politician ,US Senator from Washington, 1987-93 Brooke ,Adams -

Scholarship Boys and Children's Books

Scholarship Boys and Children’s Books: Working-Class Writing for Children in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s Haru Takiuchi Thesis submitted towards the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University, March 2015 ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores how, during the 1960s and 1970s in Britain, writers from the working-class helped significantly reshape British children’s literature through their representations of working-class life and culture. The three writers at the centre of this study – Aidan Chambers, Alan Garner and Robert Westall – were all examples of what Richard Hoggart, in The Uses of Literacy (1957), termed ‘scholarship boys’. By this, Hoggart meant individuals from the working-class who were educated out of their class through grammar school education. The thesis shows that their position as scholarship boys both fed their writing and enabled them to work radically and effectively within the British publishing system as it then existed. Although these writers have attracted considerable critical attention, their novels have rarely been analysed in terms of class, despite the fact that class is often central to their plots and concerns. This thesis, therefore, provides new readings of four novels featuring scholarship boys: Aidan Chambers’ Breaktime and Dance on My Grave, Robert Westall’s Fathom Five, and Alan Garner’s Red Shift. The thesis is split into two parts, and these readings make up Part 1. Part 2 focuses on scholarship boy writers’ activities in changing publishing and reviewing practices associated with the British children’s literature industry. In doing so, it shows how these scholarship boy writers successfully supported a movement to resist the cultural mechanisms which suppressed working-class culture in British children’s literature. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

The Creation of the Television Arts Documentary

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Mary M. Irwin Article Title: Monitor: The Creation of the Television Arts Documentary Year of publication: 2011 Link to published article: http;//dx.doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2011.0042 Publisher statement: © Cambridge University Press Citation information: Journal of British Cinema and Television. Volume 8, Page 322-336 DOI 10.3366/jbctv.2011.0042, ISSN 1743-4521, Available Online October 2011 Monitor: The Creation of the Television Arts Documentary Mary M. Irwin Monitor (BBC, 1958–65), a series which showcased the arts and their creators and was presented by Huw Wheldon, is now remembered as the flagship of late 1950s and early 1960s arts documentary television broadcasting. In Arts TV: A History of Arts Television in Britain, John Walker describes Monitor as ‘a crucially important early series’ (1993: 45), arguing that ‘no one could deny its ground-breaking achievements’ (ibid.: 49). John Wyver, in Vision On: Film, Television and the Arts in Britain, called Monitor ‘among the BBC’s most celebrated contributions to “good broadcasting’’ ’ (2007: 27).1 In the edited collection Experimental British Te l e v i s i o n , Jamie Sexton refers to Monitor as the ‘BBC’s critically acclaimed arts series’ (Mulvey and Sexton 2007: 90), while Kay Dickinson, in the same collection, refers to it as a ‘well respected fortnightly Sunday arts magazine programme’, pointing out that this was where Ken Russell first made his name (ibid.: 70).