The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 Min)

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 min) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard Written by George Bernard Shaw (play, scenario & dialogue), W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple (uncredited), Anatole de Grunwald (uncredited), Kay Walsh (uncredited) Produced by Gabriel Pascal Original Music by Arthur Honegger Cinematography by Harry Stradling Edited by David Lean Art Direction by John Bryan Costume Design by Ladislaw Czettel (as Professor L. Czettel), Schiaparelli (uncredited), Worth (uncredited) Music composed by William Axt Music conducted by Louis Levy Leslie Howard...Professor Henry Higgins Wendy Hiller...Eliza Doolittle Wilfrid Lawson...Alfred Doolittle Marie Lohr...Mrs. Higgins Scott Sunderland...Colonel George Pickering GEORGE BERNARD SHAW [from Wikipedia](26 July 1856 – 2 Jean Cadell...Mrs. Pearce November 1950) was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the David Tree...Freddy Eynsford-Hill London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing Everley Gregg...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many Leueen MacGrath...Clara Eynsford Hill highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for Esme Percy...Count Aristid Karpathy drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings address prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy Academy Award – 1939 – Best Screenplay which makes their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined George Bernard Shaw, W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple education, marriage, religion, government, health care, and class privilege. ANTHONY ASQUITH (November 9, 1902, London, England, UK – He was most angered by what he perceived as the February 20, 1968, Marylebone, London, England, UK) directed 43 exploitation of the working class. -

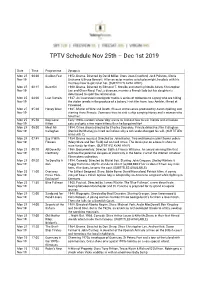

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

* Hc Omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1

* hc omslag Film Architecture 22-05-2007 17:10 Pagina 1 Film Architecture and the Transnational Imagination: Set Design in 1930s European Cinema presents for the first time a comparative study of European film set design in HARRIS AND STREET BERGFELDER, IMAGINATION FILM ARCHITECTURE AND THE TRANSNATIONAL the late 1920s and 1930s. Based on a wealth of designers' drawings, film stills and archival documents, the book FILM FILM offers a new insight into the development and signifi- cance of transnational artistic collaboration during this CULTURE CULTURE period. IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION European cinema from the late 1920s to the late 1930s was famous for its attention to detail in terms of set design and visual effect. Focusing on developments in Britain, France, and Germany, this book provides a comprehensive analysis of the practices, styles, and function of cine- matic production design during this period, and its influence on subsequent filmmaking patterns. Tim Bergfelder is Professor of Film at the University of Southampton. He is the author of International Adventures (2005), and co- editor of The German Cinema Book (2002) and The Titanic in Myth and Memory (2004). Sarah Street is Professor of Film at the Uni- versity of Bristol. She is the author of British Cinema in Documents (2000), Transatlantic Crossings: British Feature Films in the USA (2002) and Black Narcis- sus (2004). Sue Harris is Reader in French cinema at Queen Mary, University of London. She is the author of Bertrand Blier (2001) and co-editor of France in Focus: Film -

Exeter Blitz for Adobe

Devon Libraries Exeter Blitz Factsheet 17 On the night of 3 rd - 4 th of May 1942, Exeter suffered its most destructive air raid of the Second World War. 160 high explosive bombs and 10,000 incendiary devices were dropped on the city. The damage inflicted changed the face of the city centre forever. Exeter suffered nineteen air raids between August 1940 and May 1942. The first was on the night of 7 th – 8 th of August 1940, when a single German bomber dropped five high explosive bombs on St. Thomas. Luckily no one was hurt and the damage was slight. The first fatalities were believed to have been in a raid on 17 th September 1940, when a house in Blackboy Road was destroyed, killing four boys. In most of the early raids it is likely that the city was not the intended target. The Luftwaffe flew over Exeter on its way towards the industrial cities to the north. It is possible that these earlier attacks on Exeter were caused by German bombers jettisoning unused bombs on the city when returning from raiding these industrial targets. It was not until the raids of 1942 that Exeter was to become the intended target. The town of Lubeck is a port on the Baltic; it had fine medieval architecture reflecting its wealth and importance. Although it was used to supply the German army and had munitions factories on the outskirts of the town, it was strategically unimportant. The bombing of this town on the night of 28 th – 29 th March on the orders of Bomber Command is said to be the reason why revenge attacks were carried out on ‘some of the most beautiful towns in England’. -

Mise En Page 1

octobre 2013 La lettre n° 235 R D - e g n a h c u D e h p o t s i r h C r a p é i h p a r g o t o h p , r i o s e c s t r o m t n o s s o r é h s o N , t l u a r r e P d i v a D e d m l i f les entretiens de l'AFC : u d e g a n r AFC u THIERRY ARBOGAST o t e l r pour Malavita u s e de Luc Besson > p. 16 n è t s g n CHRISTOPHE DUCHANGE u t u a pour Nos héros sont morts ce soir s e l u de David Perrault > p. 18 o p m a AFC ' d JEANNE LAPOIRIE n o i t pour Un château en Italie a l l a t de Valeria Bruni Tedeschi > p. 20 s n I e s i e a e u i FILMS AFC SUR LES ÉCRANS > p. 2 ACTIVITÉS AFC > p. 4 ç q h i n p h a r a s p r F r a g r u IN MEMORIAM > p. 4 FESTIVALS > p. 8 ÇÀ ET LÀ > p. 9 n o e g t o t i o o c t t e h a a i r i p c m LA CST > p. 22 NOS ASSOCIÉS > p. 23 PRESSE > p. 26 d o a é l s s n s i e e C d d A LECTURE > p. -

Vierteljahreszeitschrift Für Stadtgeschichte, Stadtsoziologie, Denkmalpflege Und Stadtentwicklung

E 61292 30. Jahrgang' 2003 • Heft 3 Vierteljahreszeitschrift für Stadtgeschichte, Stadtsoziologie, Denkmalpflege und Stadtentwicklung Begründet von Otto Borst Schwerpunkt: Stadt mit Sicherheit Herausgegeben von Volker Roscher Die alte Stadt 30. Jahrgang Die alte Stadt Heft 3/ 2003 Vierteljahreszeitschriftfür Stadtgeschichte, Stadtsoziologie, Denkmalpflegeund Stadtentwicklung Herausgegeben von der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Die Alte Stadt in Verbindung mit Gerd Albers, Helmut Böhme, August Gebeßler, Stadt mit Sicherheit Friedrich Mielke, Jürgen Reulecke, Erika Spiegel und Jürgen Zieger Begründet von Otto Borst Zwischen Unsicherheit, Kriminalstatistik und Law-and-order-Politik Redaktionskollegium: zur Fortsetzung bis auf Widerruf. Kündigungen Herausgegeben von Volker Roscher HANS SCHULTHEISS ( Chefredakteur) - Prof. Dr. des Abonnements können nur zum Ablauf eines AUGUST GEBESSLER (Geschäftsführer der Arbeitsge Jahres erfolgen und müssen bis zum I5. Novem Abhandlungen meinschaft Die alte Stadt e.V.) - Dr. WINFRIED ber des laufenden Jahres beim Verlag eingegan MÖNCH (Besprechungen). gen sein. VOLKER ROSCHER, Editorial .. ........................................................................... 181 Prof. Dr. HARALD BODENSCHATZ, TU Berlin, Institut INGRID BREcKNER / KLAUS SESSAR, Unsicherheiten in der Stadt und für Sozialwissenschaften - Prof. Dr. DIETRICH Verlag: Franz Steiner Verlag Wiesbaden GmbH, ............. ........ .. ... .............................. DENECKE, Universitat Göttingen, Geographisches Sitz Stuttgart Kriminalitätsfurcht. Ein -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Proud to Sponsor Canterbury Festival

CANTERBURY FESTIVAL KENT’S INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 20 OCT - 3 NOV 2018 canterburyfestival.co.uk i Welcome & Sponsors Box Office: 01227 787787 canterburyfestival.co.uk WELCOME PARTNER AND PRINCIPAL SPONSOR FUNDERS from Rosie Turner Festival Director Per ardua ad astra (through struggle to the stars) has been our watchword in preparing this Canterbury Christ Church University welcomes the SPONSORS year’s star-studded Festival. opportunity to work with Canterbury Festival in 2018, for the ninth consecutive year. We are delighted to be Massive thanks to our sponsors and associated with such a prestigious and popular event in donors – led by Canterbury Christ the city, as both Principal Sponsor and Partner. Church University – who have stayed Venue Sponsor loyal, increased their commitment, Canterbury Festival plays both a vital role in the city’s or joined us for the first time, proving excellent cultural programme and the UK festival that Canterbury needs, loves and calendar. It brings together the people of Canterbury, deserves a fantastic Festival. Now visitors, and international artists in an annual celebration you can support us by booking early, of arts and culture, which contributes to a prosperous telling your friends, organising a and more vibrant city. This year’s Festival promises to work’s night out… we need to sell be as ambitious and inspirational as ever, with a rich Technical Sponsor more tickets than ever before and and varied programme. there’s lots to tempt you. The University is passionate about, and contributes From Knights and Dames to significantly to, the region’s creative economy. We are performing Socks – please look proud to work closely with a range of local and national through the entire programme as cultural organisations, such as the Canterbury Festival, some of our unique events defy to collectively offer an artistically vibrant, academically simple classification. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243