The Representation of Transgressive Female Desire in Daughter Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, It’s been really heart-warming to read all your lovely letters and emails of support about what Talking Pictures TV has meant to you during lockdown, it means so very much to us here in the projectionist’s box, thank you. So nice to feel we have helped so many of you in some small way. Spring is on the horizon, thank goodness, and hopefully better times ahead for us all! This month we are delighted to release the charming filmThe Angel Who Pawned Her Harp, the perfect tonic, starring Felix Aylmer & Diane Cilento, beautifully restored, with optional subtitles plus London locations in and around Islington such as Upper Street, Liverpool Road and the Regent’s Canal. We also have music from The Shadows, dearly missed Peter Vaughan’s brilliant book; the John Betjeman Collection for lovers of English architecture, a special DVD sale from our friends at Strawberry, British Pathé’s 1950 A Year to Remember, a special price on our box set of Together and the crossword is back! Also a brilliant book and CD set for fans of Skiffle and – (drum roll) – The Talking Pictures TV Limited Edition Baseball Cap is finally here – hand made in England! And much, much more. Talking Pictures TV continues to bring you brilliant premieres including our new Saturday Morning Pictures, 9am to 12 midday every Saturday. Other films to look forward to this month include Theirs is the Glory, 21 Days with Vivien Leigh & Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith’s Fanny By Gaslight, The Spanish Gardener with Dirk Bogarde, Nijinsky with Alan Bates, Woman Hater with Stewart Granger and Edwige Feuillère,Traveller’s Joy with Googie Withers, The Colour of Money with Paul Newman and Tom Cruise and Dangerous Davies, The Last Detective with Bernard Cribbins. -

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

Siriusxm and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats for All

NEWS RELEASE SiriusXM and Pandora Present Halloween at Home with Music, Talk, Comedy and Entertainment Treats For All 10/13/2020 The world is scary enough, so have some spooky fun by streaming Halloween programming on home devices & mobile apps NEW YORK, Oct. 13, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- SiriusXM and Pandora announced today they will feature a wide variety of exclusive Halloween-themed programming on both platforms. With traditional Halloween activities aected by the Covid-19 pandemic, SiriusXM and Pandora plan to help families and listeners nd creative and safe ways to keep the spirit alive with endless hours of music and entertainment for the whole family. Beginning on October 15, SiriusXM will air extensive programming including everything from scary stories, to haunted house-inspired sounds, to Halloween-themed playlists across SiriusXM's music, talk, comedy and entertainment channels. Pandora oers a lineup of Halloween stations and playlists for the whole family, including the newly updated Halloween Party station with Modes, and a hosted playlist by Halloween-obsessed music trio LVCRFT. All programming from SiriusXM and Pandora is available to stream online on the SiriusXM and Pandora mobile apps, and at home on a wide variety of connected devices. SiriusXM's Scream Radio channel is an annual tradition for Halloween enthusiasts, providing the ultimate bone- chilling soundtrack of creepy sound eects, traditional Halloween favorite tunes, ghost stories, spooky music from classic horror lms, and more. The limited run channel will also feature a top 50 Halloween song countdown, "The Freaky 50" and will play scary score music, sound eects, spoken word stories 24 hours a day, and will set the tone for a spooktacular haunted house vibe. -

Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock

The Hitchcock 9 Silent Films of Alfred Hitchcock Justin Mckinney Presented at the National Gallery of Art The Lodger (British Film Institute) and the American Film Institute Silver Theatre Alfred Hitchcock’s work in the British film industry during the silent film era has generally been overshadowed by his numerous Hollywood triumphs including Psycho (1960), Vertigo (1958), and Rebecca (1940). Part of the reason for the critical and public neglect of Hitchcock’s earliest works has been the generally poor quality of the surviving materials for these early films, ranging from Hitchcock’s directorial debut, The Pleasure Garden (1925), to his final silent film, Blackmail (1929). Due in part to the passage of over eighty years, and to the deterioration and frequent copying and duplication of prints, much of the surviving footage for these films has become damaged and offers only a dismal representation of what 1920s filmgoers would have experienced. In 2010, the British Film Institute (BFI) and the National Film Archive launched a unique restoration campaign called “Rescue the Hitchcock 9” that aimed to preserve and restore Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films — The Pleasure Garden (1925), The Lodger (1926), Downhill (1927), Easy Virtue (1927), The Ring (1927), Champagne (1928), The Farmer’s Wife (1928), The Manxman (1929), and Blackmail (1929) — to their former glory (sadly The Mountain Eagle of 1926 remains lost). The BFI called on the general public to donate money to fund the restoration project, which, at a projected cost of £2 million, would be the largest restoration project ever conducted by the organization. Thanks to public support and a $275,000 dona- tion from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation in conjunction with The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, the project was completed in 2012 to coincide with the London Olympics and Cultural Olympiad. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

What Are You So Scared About?: Understanding the False

What Are You So Scared About?: Understanding the False Fear Response to Horror Films Sarah Seyler HSS 490-01H Faculty Director: Dr. Jeffrey Adams April 22nd, 2019 1 When a horror movie delivers a scare to an audience member, it is able to achieve something that is entirely illogical; it has made someone scared of something that poses no threat. So what is the logic behind a horror film? What aspects make a horror movie, something that can pose no physical threat, scary? In order to solve this question, many different aspects of filmmaking in horror will be looked at, including filmmaking techniques, psychological manipulation through storytelling, and the exploration of certain cultural elements in horror films that contextualize the fears a society has. By analyzing the different aspects of horror, we can understand how and why a movie is able to override the rational side of a viewer’s brain and make them scared. We can then understand why these aspects cause the body to have a physical reaction to the false threat, and why some people respond more intensely to horror than others. The goal of any movie is to elicit some sort of emotional response in the audience observing the film, and this is no different for horror movies. However, instead of a joy or sadness response, the horror movie aims to cause an observer to feel some sort of fear -- whether that be an immediate physical fear or longer-lasting psychological distress. Scaring people may sound simple, however it is actually a pretty complex process, as the film must be logical enough for the audience to buy into, allowing them to become immersed in the movie. -

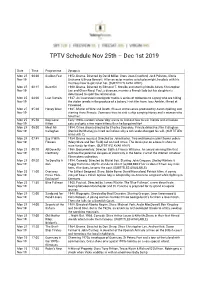

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

Historical Essays Excerpts

Excerpts from: Historical Essays By Deborah O'Toole Copyright ©Deborah O'Toole All rights reserved. No part of this document may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author. HISTORICAL ESSAYS *EXCERPTS ONLY* By Deborah O'Toole ABOUT Deborah O'Toole is the author of several historical essays, which are now available in e-book format. The articles first appeared in Ambermont Magazine when Deborah was a staff writer for the publication. The essays include topics ranging from Billy the Kid, Anne Boleyn, Lizzie Borden, Michael Collins, Loch Ness Monster, U.S. Political Parties and Jack the Ripper. The essays are now available at Class Notes, or can be obtained from Amazon (Kindle), Barnes & Noble (Nook) and Kobo Books (multiple formats). For more, go to: https://deborahotoole.com/essays.htm 2 HISTORICAL ESSAYS *EXCERPTS ONLY* By Deborah O'Toole BILLY THE KID (excerpt only) William Henry McCarty (aka Billy the Kid) was born in New York in 1859. The actual day of his birth is still in question. Some claim it was November 23, 1859 while others (such as writer Ash Upson who helped Pat Garrett pen his memoirs), insist the date was November 21, 1859 (which also happened to be Upson's birthday). Whatever the case, it is generally agreed that William McCarty was born in late 1859. Several historians claim young William's real father was named Bonney, which may account for his use of the name as an alias in later years. Young William's mother, Catherine, later married a man by the name of Henry McCarty, who became the father of William’s younger brother, Joseph. -

Xavier Aldana Reyes, 'The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror

1 Originally published in/as: Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’, Journal of Italian Cinema and Media Studies, 5.2 (2017), 229–44. DOI link: 10.1386/jicms.5.2.229_1 Title: ‘The Cultural Capital of the Gothic Horror Adaptation: The Case of Dario Argento’s The Phantom of the Opera and Dracula 3D’ Author: Xavier Aldana Reyes Affiliation: Manchester Metropolitan University Abstract: Dario Argento is the best-known living Italian horror director, but despite this his career is perceived to be at an all-time low. I propose that the nadir of Argento’s filmography coincides, in part, with his embrace of the gothic adaptation and that at least two of his late films, The Phantom of the Opera (1998) and Dracula 3D (2012), are born out of the tensions between his desire to achieve auteur status by choosing respectable and literary sources as his primary material and the bloody and excessive nature of the product that he has come to be known for. My contention is that to understand the role that these films play within the director’s oeuvre, as well as their negative reception among critics, it is crucial to consider how they negotiate the dichotomy between the positive critical discourse currently surrounding gothic cinema and the negative one applied to visceral horror. Keywords: Dario Argento, Gothic, adaptation, horror, cultural capital, auteurism, Dracula, Phantom of the Opera Dario Argento is, arguably, the best-known living Italian horror director.