Darrol Blake Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Study to Examine Issues Relating to the Spread of Eastern Redcedar Trees

2018 COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES NEBRASKA LEGISLATURE LR 387 Interim Study Report Interim study to examine issues relating to the spread of Eastern Redcedar Trees ONE HUNDRED-FIFTH LEGISLATURE SECOND SESSION NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE MEMBERS Senator Dan Hughes, Chairperson Senator Bruce Bostelman, Vice-Chairperson Senator Joni Albrecht Senator Suzanne Geist Senator Rick Kolowski Senator John McCollister Senator Dan Quick Senator Lynne Walz LR 387 NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE I. LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION 387 II. MEMORANDUM, SENATOR DAN HUGHES, CHAIRMAN III. AUGUST 31, 2018, HEARING TRANSCRIPT IV. EXHIBITS 1. Dr. Dirac Twidwell, UNL Dept. of Agronomy and Horticulture 2. Scott Smathers, Conservation Roundtable 3. Craig Derickson, Natural Resources Conservation Service 4. Adam Smith, Nebraska Forest Service 5. Sue Kirkpatrick, Nebraska Prescribed Fire Council 6. Shelly Kelly, Sandhills Task Force 7. Dean Edson, Nebraska Association of Resources Districts 8. Curtis Gotschall, Upper Elkhorn NRD 9. Dennis Schueth, Upper Elkhorn NRD 10, 11, 12. Terry Julesgard, Lower Niobrara NRD 13. Russell Callan, Lower Loup NRD 14. Katie Torpy Carroll, The Nature Conservancy 15. John Erixson 16. Matthew Holte 17. Tell Deatrich, Loess Conyon Rangeland Alliance 18. Frank Andelt 19. Dennis Oelschlager, Tri-County Prescribed Burn Association 20, 21. Allan Mortensen, Tri-County Prescribed Burn Association V. LETTERS FOR THE RECORD Patrick O’Brien, Upper Niobrara White NRD Roger Suhr, Chadron NE Kelsi Wehrman, Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever Mike Murphy, Middle Niobrara NRD Annette Sudbeck, Lewis & Clark NRD Anna Baum, Upper Loup NRD Scott Smathers, Nebraska Sportsmen Foundation MEMORANDUM TO: NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE MEMBERS FROM: SEN. DAN HUGHES, CHAIRMAN DATE: NOVEMBER, 2018 SUBJECT: LR 387 The Natural Resources Committee held a public hearing on August 31, 2018, in Lincoln, Nebraska, on LR 387. -

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: a Critical Introduction

The Finance and Production of Independent Film and Television in the UK: A Critical Introduction Vital Statistics General Population: 64.1m Size: 241.9 km sq GDP: £1.9tr (€2.1tr) Film1 Market share of UK independent films in 2015: 10.5% Number of feature films produced: 201 Average visits to cinema per person per year: 2.7 Production spend per year: £1.4m (€1.6) TV2 Audience share of the main publicly-funded PSB (BBC): 72% Production spend by PSBs: £2.5bn (€3.2bn) Production spend by commercial channels (excluding sport): £350m (€387m) Time spent watching television per day: 193 minutes (3hrs 13 minutes) Introduction This chapter provides an overview of independent film and television production in the UK. Despite the unprecedented levels of convergence that characterise the digital era, the UK film and television industries remain distinct for several reasons. The film industry is small and fragmented, divided across the two opposing sources of support on which it depends: large but uncontrollable levels of ‘inward-investment’ – money invested in the UK from overseas – mainly from the US, and low levels of public subsidy. By comparison, the television industry is large and diverse, its relative stability underpinned by a long-standing infrastructure of 1 Sources: BFI 2016: 10; ‘The Box Office 2015’ [market share of UK indie films] ; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [cinema visits per per person]; BFI 2016: 6; ‘Exhibition’ [average visits per person]; BFI 2016: 3; ‘Screen Sector Production’ [production spend per year]. 2 Sources: Oliver & Ohlbaum 2016: 68 [PSB audience share]; Ofcom 2015a: 3 [PSB production spend]; Ofcom 2015a: 8. -

Number 42 Michaelmas 2018

Number 42 Michaelmas 2018 Number 42 Michaelmas Term 2018 Published by the OXFORD DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY [email protected] Contents 4 The Time of Doctor Puppet: interview with Alisa Stern J A 9 At Last, the Universe is Calling G H 11 “I Can Hear the Sound of Empires Toppling’ : Deafness and Doctor Who S S 14 Summer of ‘65 A K 17 The Barbara Wright Stuff S I 19 Tonight, I should liveblog… G H 22 Love Letters to Doctor Who: the 2018 Target novelizations R C 27 Top or Flop? Kill the Moon J A, W S S S 32 Haiku for Kill the Moon W S 33 Limerick for Kill the Moon J A 34 Utopia 2018 reports J A 40 Past and present mixed up: The Time Warrior M K 46 Doctors Assemble: Marvel Comics and Doctor Who J A 50 The Fan Show: Peter Capaldi at LFCC 2018 I B 51 Empty Pockets, Empty Shelves M K 52 Blind drunk at Sainsbury’s: Big Finish’s Exile J A 54 Fiction: A Stone’s Throw, Part Four J S 60 This Mid Curiosity: Time And Relative Dimensions In Shitposting W S Front cover illustration by Matthew Kilburn, based on a shot from The Ghost Monument, with a background from Following Me Home by Chris Chabot, https://flic.kr/p/i6NnZr, (CC BY-NC 2.0) Edited by James Ashworth and Matthew Kilburn Editorial address [email protected] Thanks to Alisa Stern and Sophie Iles This issue was largely typeset in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro by Adobe; members of the Alegreya family, designed by Juan Pablo del Peral; members of the Saira family by Omnibus Type; with Arial Rounded MT Bold, Baskerville, Bauhaus 93, and Gotham Narrow Black. -

Delivering Quality First – Page 2

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel A future plan Delivering Quality First – Page 2 Photo courtesy of Jeff Overs November 2011 • Issue 8 tales of Print edition of Musical televison ariel to close memories Centre Page 2 Page 6 Page 9 NEWS • MEMoriES • ClaSSifiEdS • Your lEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 uPdatE froM thE bbC commissioning and scheduling will be • More landmark output for Radio 4 (which closely aligned. sees its overall budget hardly changed). Delivering Quality First • Job grading, redundancy terms and • More money for the Proms. unpredictability allowances will be • The further rollout of HD and DAB. Mark Thompson sets out ‘a plan for living within our means’ as ‘modernised’ and reformed. A consultation he reveals job losses, output changes, relocations, structured process on those proposals begins Union response immediately. The National Union of Journalists issued a re-investment in a digital public space, and new content and • Production will be streamlined into a swift response to the announcement, calling programmes on BBC services. single UK production economy. for the licence fee negotiations to be re- • Radio and TV commissioning for Science opened and ‘a proper public debate about Fewer staff, a flatter structure, more jobs • All new daytime programming will be and Music will be brought together. BBC funding’. shifting to Salford and more output from on BBC One. In a statement the NUJ said: ‘The BBC will outside London, these are the conclusions of • BBC Two’s daytime output will focus on Reinvestment not be the same organisation if these cuts go the Delivering Quality First process. -

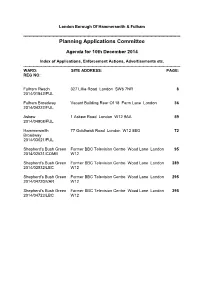

Planning Applications Committee

London Borough Of Hammersmith & Fulham --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Planning Applications Committee Agenda for 10th December 2014 Index of Applications, Enforcement Actions, Advertisements etc. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- WARD: SITE ADDRESS: PAGE: REG NO: Fulham Reach 327 Lillie Road London SW6 7NR 8 2014/01842/FUL Fulham Broadway Vacant Building Rear Of 18 Farm Lane London 36 2014/04222/FUL Askew 1 Askew Road London W12 9AA 59 2014/04908/FUL Hammersmith 77 Goldhawk Road London W12 8EG 72 Broadway 2014/03021/FUL Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 95 2014/02531/COMB W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 289 2014/02532/LBC W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 295 2014/04720/VAR W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 395 2014/04723/LBC W12 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ward: Fulham Reach Site Address: 327 Lillie Road London SW6 7NR © Crown Copyright. All Rights Reserved. London Borough Hammersmith and Fulham LA100019223 (2013). For identification purposes only - do not scale. Reg. No: Case Officer: 2014/01842/FUL Roy Asagba-Power Date Valid: Conservation Area: 23.04.2014 Committee Date: 10.12.2014 Applicant: Mr Ashok Patel 35/37 Ludgate Hill London EC4M 7JN Description: Demolition of existing office buildings (Class B1) and the erection of 8 x two storey plus- basement single family dwelling houses (Class C3) with roof terraces at first floor level; formation of refuse and cycle storage; installation of two new access gates fronting Lillie Road elevation; replacement of existing power sub-station and formation of a new underground power sub-station in between properties 17-20 and 337 Lillie Road. -

Unseen Horrors: the Unmade Films of Hammer

Unseen Horrors: The Unmade Films of Hammer Thesis submitted by Kieran Foster In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2019 Abstract This doctoral thesis is an industrial study of Hammer Film Productions, focusing specifically on the period of 1955-2000, and foregrounding the company’s unmade projects as primary case studies throughout. It represents a significant academic intervention by being the first sustained industry study to primarily utilise unmade projects. The study uses these projects to examine the evolving production strategies of Hammer throughout this period, and to demonstrate the methodological benefits of utilising unmade case studies in production histories. Chapter 1 introduces the study, and sets out the scope, context and structure of the work. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literature, considering unmade films relation to studies in adaptation, screenwriting, directing and producing, as well as existing works on Hammer Films. Chapter 3 begins the chronological study of Hammer, with the company attempting to capitalise on recent successes in the mid-1950s with three ambitious projects that ultimately failed to make it into production – Milton Subotsky’s Frankenstein, the would-be television series Tales of Frankenstein and Richard Matheson’s The Night Creatures. Chapter 4 examines Hammer’s attempt to revitalise one of its most reliable franchises – Dracula, in response to declining American interest in the company. Notably, with a project entitled Kali Devil Bride of Dracula. Chapter 5 examines the unmade project Nessie, and how it demonstrates Hammer’s shift in production strategy in the late 1970s, as it moved away from a reliance on American finance and towards a more internationalised, piece-meal approach to funding. -

The Story of the Shipping Forecast, from the Man Who Read It Page 10

The newspaper for BBC pensioners - with highlights from Ariel For those in peril on the sea The story of the Shipping Forecast, from the man who read it Page 10 July 2011 • Issue 5 original Harryhausen 40 years of models on 30 years of the local radio display Space Shuttle remembered Page 2 Page 5 Page 6 NEWS • LifE aftEr auNtiE • CLaSSifiEdS • Your LEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 GENEraL NEWS Ray Harryhausen’s iconic animation models and artwork at the National Media Museum Phil Oates, Acting Senior Press Officer at the National Media Museum in Bradford, writes about an interesting new exhibition in Bradford. Ray Harryhausen, and have been on show in Bradford since May 19. They will be displayed alongside examples of Harryhausen’s artwork for the films. Further objects from the Ray Harryhausen Collection will be exhibited at later dates as part of an ongoing rolling programme. The display is one of the first steps following last year’s agreement with The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation to deposit the animator’s complete collection with the National Media Museum, which was announced during Harryhausen’s 90th birthday celebrations. Ray Harryhausen commented, ‘Knowing that my Collection is going to be cared for by the Museum, and that my Foundation will continue to be directly involved, is a great comfort and an acknowledgement that my work and art will be preserved for new Jason fights the skeletons, key drawing, Jason and the Argonauts (1963), © Ray Harryhausen. Courtesy of the Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation film makers to study and hopefully continue to appreciate.’ Some of the most famous models from Michael Harvey, the Museum’s Curator Centre of Excellence It aims to be the best museum in the the history of fantasy cinema are on of Cinematography, said, ‘To have agreed ‘This is perhaps one of the most important world for inspiring people to learn about, display at the National Media Museum with Ray and the Foundation to bring this cinematic collections in the world, says Tony engage with and create media. -

The British Film Industry

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee The British Film Industry Sixth Report of Session 2002–03 Volume I HC 667-I House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee The British Film Industry Sixth Report of Session 2002–03 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 9 September 2003 HC 667-I Published on 18 September 2003 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Gerald Kaufman MP (Labour, Manchester Gorton) (Chairman) Mr Chris Bryant MP (Labour, Rhondda) Mr Frank Doran MP (Labour, Aberdeen) Michael Fabricant MP (Conservative, Lichfield) Mr Adrian Flook MP (Conservative, Taunton) Alan Keen MP (Labour, Feltham and Heston) Miss Julie Kirkbride MP (Conservative, Bromsgrove) Rosemary McKenna MP (Labour, Cumbernauld and Kilsyth) Ms Debra Shipley (Labour, Stourbridge) John Thurso MP (Liberal Democrat, Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) Derek Wyatt MP (Labour, Sittingbourne and Sheppey) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at http://www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/culture__media_and_sport. -

Philip A. Crawley, Career Summary Statement I Have 28 Years Of

Philip A. Crawley, career summary statement I have 28 years of television / IT / digital-film engineering and have worked in studios, post- production, outside broadcast, transmission and data-centres. I am BBC ETSI qualified in broadcast engineering with my first degree in maths and programming. I have seen firsthand the very best and worst examples of television workflows and probably have a better understanding of current TV technology and practise than any other engineer of my generation. History After graduation with an honours degree in maths and programming I spent five years at the BBC in the engineering department of Television News and Current Affairs, firstly at Lime Grove Studios and then at Television Centre and White City. Since 1994 I have been running engineering departments in large TV facilities and latterly a leading Systems Integrator. My team has varied between a couple of engineers and dozens of wiremen and engineers. Having run the technical sides of such productions as “Big Brother” and “Fame Academy” as well as PM’ing > £1m broadcast builds I feel my organisational record is second to none. Having to run pre-sales, project management and hand-over training has given me excellent communication skills with both colleagues and customers. Additionally I deliver all of root6’s training courses and present at trade shows, particularly in the area of IP networks and convergence. I have maintained my interest in software – I wrote the ingest automation system for the in-house developed MAM used on Big Brother and currently implement custom hardware using the Arduino platform (development in C). -

Conservation Area Character Appraisal & Management Plan August 2021

Milstead Conservation Area Character Appraisal & Management Plan August 2021 DRAFT FOR PUBLIC CONSULTATION Contents FOREWORD 4 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1. Milstead Conservation Area...................................................................................... .....5 1.2 The Purpose of Conservation Areas................................................................................5 1.3 The Purpose and Status of this Character Appraisal.......................................................5 2.0. MILSTEAD CONSERVATION AREA 2.1 Summary of Significance and Special Interest................................................................ 7 2.2 Geographic character and Historical Development........................................................ 8 2.3 Topography Geology and Landscape Setting...................................................................19 2.4 Character Appraisal.........................................................................................................24 3.0. CONSERVATION AREAS MANAGEMENT STRATEGY 3.1. Planning Policy and Guidance .........................................................................................51 3.2. Buildings at Risk.............................................................................................................. 52 3.3. Condition and Forces for Change....................................................................................52 3.4. Management Objectives and Approach..........................................................................53 3.5. Conservation -

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg

Ealing Studios and the Ealing Comedies: the Tip of the Iceberg ROBERT WINTER* In lecture form this paper was illustrated with video clips from Ealing films. These are noted below in boxes in the text. My subject is the legendary Ealing Studios comedies. But the comedies were only the tip of the iceberg. To show this I will give a sketch of the film industry leading to Ealing' s success, and of the part played by Sir Michael Balcon over 25 years.! Today, by touching a button or flicking a switch, we can see our values, styles, misdemeanours, the romance of the past and present-and, with imagination, a vision of the" future. Now, there are new technologies, of morphing, foreground overlays, computerised sets, electronic models. These technologies affect enormously our ability to give currency to our creative impulses and credibility to what we do. They change the way films can be produced and, importantly, they change the level of costs for production. During the early 'talkie' period there many artistic and technical difficulties. For example, artists had to use deep pan make-up to' compensate for the high levels of carbon arc lighting required by lower film speeds. The camera had to be put into a soundproof booth when shooting back projection for car travelling sequences. * Robert Winter has been associated with the film and television industries since he appeared in three Gracie Fields films in the mid-1930s. He joined Ealing Studios as an associate editor in 1942 and worked there on more than twenty features. After working with other studios he became a founding member of Yorkshire Television in 1967. -

Ashpan Number 114 Number 114 Summer 2017

111144 Ickenham and District Society of Model Engineers Summer 2017 Ashpan Number 114 Number 114 Summer 2017 114 Contents: 2 Cover Story 3 Ashpan Notebook 4 Airlander 10 - Hybrid Air Vehicle 8 Chairman's Chat 9 The Rise and Fall of Television Centre Ickenham & District Society of Model Engineers was founded on 8th October 1948. Ickenham and District Society of Model Engineers, a company limited by guarantee, was incorporated on 10th September 1999. Registered in England No: 3839364. Website: WWW.IDSME.CO.UK IDSME Members Message Board: http://idsme001.proboards.com Hon. Secretary and Registered Office: David Sexton, 25 Copthall Road East, Ickenham, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB10 8SD. Ashpan is produced for members of Ickenham and District Society of Model Engineers by Patrick Rollin, 84 Lawrence Drive, Ickenham, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UB10 8RW Email: [email protected] Summer 2017 1 Cover Story Happenings at IDSME By the time you read this the 2017 running season will be almost two- thirds done. The cover photograph shows one of many passenger trains that we have run during the year so far. Mike Werrell is seen at the controls of club locomotive Lady Patricia on the June running day. This locomotive has been a regular performer on running days this year, following a lot of hard work to get it into a serviceable condition, and this was one of the few occasions that somebody managed to prise Harry Wilcox away from the controls of this locomotive. On the same day Michael Proudfoot (inside front cover top) passes the junction signal while driving Mark Hamlin’s R1 single-handed, the other hand being engaged in the rather more important activity of carrying a cup of tea.