Television for Women: Generation, Gender and the Everyday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Dee, Mike (1996) Sun, sea, sex, sand and conservatism in the Australian television soap opera. Young People Now, March, pp. 1-5. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/62594/ c Copyright 1996 [please consult the author] This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. Author’s final version of article for Young People Now (published March 1996) Sun, Sea, Sex, Sand and Conservatism in the Australian Television Soap Opera In this issue, Mike Dee expands on his earlier piece about soap operas. -

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

The Future of The

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting Some thoughts Stephen Fry Before I can even think to presume to dare to begin to expatiate on what sort of an organism I think the British Broadcasting Corporation should be, where I think the BBC should be going, how I think it and other British networks should be funded, what sort of programmes it should make, develop and screen and what range of pastries should be made available in its cafés and how much to the last penny it should pay its talent, before any of that, I ought I think in justice to run around the games field a couple of times puffing out a kind of “The BBC and Me” mini‐biography, for like many of my age, weight and shoe size, the BBC is deeply stitched into my being and it is important for me as well as for you, to understand just how much. Only then can we judge the sense, value or otherwise of my thoughts. It all began with sitting under my mother’s chair aged two as she (teaching history at the time) marked essays. It was then that the Archers theme tune first penetrated my brain, never to leave. The voices of Franklin Engelman going Down Your Way, the women of the Petticoat Line, the panellists of Twenty Questions, Many A Slip, My Word and My Music, all these solid middle class Radio 4 (or rather Home Service at first) personalities populated my world. As I visited other people’s houses and, aged seven by now, took my own solid state transistor radio off to boarding school with me, I was made aware of The Light Programme, now Radio 2, and Sparky’s Magic Piano, Puff the Magic Dragon and Nelly the Elephant, I also began a lifelong devotion to radio comedy as Round The Horne, The Clitheroe Kid, I’m Sorry I’ll Read That Again, Just A Minute, The Men from The Ministry and Week Ending all made themselves known to me. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

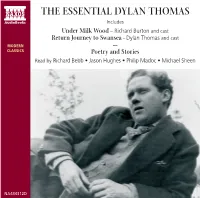

Dylan Thomas CD Booklet

THE ESSENTIAL DYLAN THOMAS Includes Under Milk Wood – Richard Burton and cast Return Journey to Swansea – Dylan Thomas and cast MODERN ∼ CLASSICS Poetry and Stories Read by Richard Bebb • Jason Hughes • Philip Madoc • Michael Sheen NA434312D Preface The voice of Dylan Thomas, on paper or on advance and 10 per cent royalty deal a recording, is unmistakable. His rich play of thereafter, to fix a date to record. He failed language and images informed all his work to show on the scheduled day, but did and it was reflected in his distinctive manner make the next date (22 February 1952) at of performance which, like his life, was the Steinway Hall in New York. The large and vivid. All this rightly made him a recording engineer was Peter Bartók, son of personality as well as a poet – certainly, he the composer Béla Bartók. Thomas recorded left an unforgettable impression on all those poems and, when he realised there was he met. It was one reason why, in the latter space left on the LPs, added Memories of part of his career, he was so popular on the Christmas. American lecture and poetry circuit. This, of course, is a marvel for history He was, perhaps, the first outstanding but presents a particular challenge for poet-performer of the recording era. Many subsequent performers of his work. of his recordings remain, from those he Performance, like fashion, is shot through made for the BBC and also for the far- with the style of the period, and Thomas’s sighted Caedmon label in the US. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

Save Kids’ TV Campaign British children’s television - on the BBC, Channel 4, ITV and Five - has been widely acknowledged as amongst the most creative and innovative in the world. But changes in children’s viewing patterns, and the ban on certain types of advertising to children, are putting huge strains on commercial broadcasters. Channel 4 no longer makes children’s programmes and ITV (until recently the UK’s second largest kids’ TV commissioner) has ceased all new children’s production. They are deserting the children’s audience because it doesn’t provide enough revenue. Channel FIVE have cut back their children’s programming too. The international channels - Disney, Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network - produce some programming here, but not enough to fill the gap, and much of that has to be international in its focus so that it can be used on their channels in other territories. The recent Ofcom report on the health of children’s broadcasting in the UK has revealed that despite the appearance of enormous choice in children’s viewing, the many channels available offer only a tiny number of programmes produced in the UK with British kids’ interests at their core. The figures are shocking – only 1% of what’s available to our kids is new programming made in the UK. To help us save the variety and quality of children’s television in the UK sign the e-petition on the 10 Downing Street website or on http://www.SaveKidsTV.org.uk ends Save Kids' TV - Name These Characters and Personalities 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Help save the quality in UK children's television Go to www.savekidstv.org.uk Save Kids TV - Answers 1 Parsley The Lion The Herbs/The Adventures of Parsley 2 Custard Roobarb and Custard 3 Timothy Claypole Rentaghost 4 Chorlton Chorlton and the Wheelies 5 Aunt Sally Worzel Gummidge 6 Errol The Hamster Roland's Rat Race, Roland Rat on TV-AM etc 7 Roland Browning Grange Hill 8 Floella Benjamin TV Presenter 9 Wizbit Wizbit 10 Zelda Terrahawks 11 Johnny Ball Presenter 12 Nobby The Sheep Ghost Train, It's Wicked, Gimme 5 etc. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Interim Study to Examine Issues Relating to the Spread of Eastern Redcedar Trees

2018 COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES NEBRASKA LEGISLATURE LR 387 Interim Study Report Interim study to examine issues relating to the spread of Eastern Redcedar Trees ONE HUNDRED-FIFTH LEGISLATURE SECOND SESSION NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE MEMBERS Senator Dan Hughes, Chairperson Senator Bruce Bostelman, Vice-Chairperson Senator Joni Albrecht Senator Suzanne Geist Senator Rick Kolowski Senator John McCollister Senator Dan Quick Senator Lynne Walz LR 387 NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE I. LEGISLATIVE RESOLUTION 387 II. MEMORANDUM, SENATOR DAN HUGHES, CHAIRMAN III. AUGUST 31, 2018, HEARING TRANSCRIPT IV. EXHIBITS 1. Dr. Dirac Twidwell, UNL Dept. of Agronomy and Horticulture 2. Scott Smathers, Conservation Roundtable 3. Craig Derickson, Natural Resources Conservation Service 4. Adam Smith, Nebraska Forest Service 5. Sue Kirkpatrick, Nebraska Prescribed Fire Council 6. Shelly Kelly, Sandhills Task Force 7. Dean Edson, Nebraska Association of Resources Districts 8. Curtis Gotschall, Upper Elkhorn NRD 9. Dennis Schueth, Upper Elkhorn NRD 10, 11, 12. Terry Julesgard, Lower Niobrara NRD 13. Russell Callan, Lower Loup NRD 14. Katie Torpy Carroll, The Nature Conservancy 15. John Erixson 16. Matthew Holte 17. Tell Deatrich, Loess Conyon Rangeland Alliance 18. Frank Andelt 19. Dennis Oelschlager, Tri-County Prescribed Burn Association 20, 21. Allan Mortensen, Tri-County Prescribed Burn Association V. LETTERS FOR THE RECORD Patrick O’Brien, Upper Niobrara White NRD Roger Suhr, Chadron NE Kelsi Wehrman, Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever Mike Murphy, Middle Niobrara NRD Annette Sudbeck, Lewis & Clark NRD Anna Baum, Upper Loup NRD Scott Smathers, Nebraska Sportsmen Foundation MEMORANDUM TO: NATURAL RESOURCES COMMITTEE MEMBERS FROM: SEN. DAN HUGHES, CHAIRMAN DATE: NOVEMBER, 2018 SUBJECT: LR 387 The Natural Resources Committee held a public hearing on August 31, 2018, in Lincoln, Nebraska, on LR 387. -

Overdeveloped Westchester? Aid in Dying Bill Fails to Pass in Albany

WESTCHESTER’S OLDEST AND MOST RESPECTED NEWSPAPERS Vol 125 Number 26 www.RisingMediaGroup.com Friday, June 24, 2016 Teens Earn Scholarships Look Out, Westchester – To Travel to Israel Project Veritas is Here Yonkers Federation of Teachers President Pat Puleo, on video footage at union offces captured by ProjectVeritas. By Dan Murphy is printed at the end of this story and has been Project Veritas, a website aimed at investi- widely reported on by News 12.) Some of the 20 students heading to Israel this summer, thanks to the UJA-Federation of New gating and exposing corruption across the coun- O’Keefe now has another undercover video York and Singer Scholarship Awards. try, has recently relocated to Westchester, and has that he is about to release featuring another West- Twenty Westchester teens were recently seph Block, Ayelet Marder and Alyssa Schwartz two exposes coming out about the doings – or chester teachers union. The second tape under- awarded Singer Scholarship Awards for summer of White Plains; Joshua Bloom, Doreen Blum, wrongdoings – in the county. scores O’Keefe’s early interest in improper ac- programs in Israel by UJA-Federation of New Sara Butman, Hadas Krasner and Sophia Peister Two weeks ago Project Veritas founder tivities in the county. York. The merit awards, funded by Fran and Saul of New Rochelle; Emily Goldberg of Amawalk; James O’Keefe released an undercover video O’Keefe recently appeared on the blog radio Singer of White Plains, help offset the cost of Is- Sydney Goodman and David Rosenberg of Rye that was taped at the headquarters of the Yon- show for the Yonkers Tribune and explained he rael programs for high school teens. -

The 100 Greatest Kids' TV Shows

The 100 Greatest Kids’ TV Shows UK TV compilation marathon : 2001 : dir. : Channel 4 : ? min prod: : scr: : dir.ph.: …………………………….……………………………………………………………………………… Guest pundits: Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 5500 2.5 0 0 1,287 - - - - - No August 2001 Broadcast Channel 4: 27/08/01. The last few years of the 20th century presented the media with a perfect occasion to conduct their own ad hoc round-ups of the century’s most influential people, most important films, best popular music etc etc. So 2001 is perhaps a little soon to be dipping back into the same baskets, yet Channel 4 has strewn the year with surveys similar to this one (see for example “Top Ten Teen Idols”). One might think such retrospectives were a clear invitation to the over-25s to bask for a short while in the kind of programming they used to enjoy – a brief escape from a television saturated with material aimed at the apolitical, pill-popping post-Thatcherite generation, breast-fed on tabloid culture. Ah but no, Channel 4 are too shrewd for that. Their retrospectives are chiefly an opportunity for that same generation to thumb their noses at everything which preceded their own miraculous lives. And so it goes with this one. It’s some reflection on the value of their poll that the two programmes topping Channel 4’s list were not even children’s programmes anyway! – “The Muppet Show” (no.2) and “The Simpsons” (no.1) never purported to be made for kids, were never broadcast in children’s TV slots, and hence not surprisingly are best favoured by adults. -

Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and Cast 1 Introduction - on a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, This Is He

POETRY UNABRIDGED John Milton Samson Agonistes Performed by Iain Glen and cast 1 Introduction - On a Festival Day 8:55 2 Chorus 1: This, this is he... 3:19 3 Samson: I hear the sound of words... 2:16 4 Chorus 1: Tax not divine disposal, wisest Men... 1:45 5 Samson: That fault I take not on me... 2:03 6 Chorus 1: Thy words to my remembrance bring... 2:33 7 Manoa: Brethren and men of Dan, for such ye seem... 3:11 8 Samson: Appoint not heavenly disposition, Father... 2:56 9 Manoa: I cannot praise thy Marriage choices, Son... 3:36 10 Manoa: With cause this hope relieves thee... 4:22 11 Chorus 1: Desire of wine and all delicious drink... 4:05 12 Samson: O that torment should not be confin’d... 2:45 13 Chorus 3: Many are the sayings of the wise... 3:07 14 Chorus 3: But who is this, what thing of Sea or Land? 1:14 15 Dalila: With doubtful feet and wavering resolution... 2:05 16 Dalila: Yet hear me Samson; not that I endeavour... 6:47 17 Samson: I thought where all thy circling wiles would end... 7:32 2 18 Chorus 1: She’s gone, a manifest Serpent by her sting... 3:24 19 Samson: Fair days have oft contracted wind and rain. 0:48 20 Harapha: I come not Samson, to condole thy chance... 7:15 21 Samson: Among the Daughters of the Philistines... 3:15 22 Chorus 1: His Giantship is gone somewhat crestfall’n..