Ashpan Number 114 Number 114 Summer 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Far Side of the Moore by Sean Grundy

Far Side Of The Moore By Sean Grundy CHARACTERS PATRICK MOORE (early 30s)...eccentric amateur astronomer PAUL JOHNSTONE (mid 30s)...BBC science producer DR HENRY KING (40s) ...soon-to-be head of the BAA PERCY WILKINS (60s) ...Moore’s mentor EILEEN WILKINS (early 20s) ...Percy’s daughter ARTHUR C CLARKE (late 30s)...Moore’s friend GERTRUDE MOORE (60s)...Moore’s mother LEONARD MIALL (40s)...BBC Head of Talks ANNOUNCER; STUDIO FM; TRANSMISSION CONTROL; HENRY KING’S SECRETARY; NEWS REPORTER; GEORGE ADAMSKI; BAA PRESIDENT Set in mid-1950s at BBC TV, BAA meeting room and Patrick’s home, East Grinstead. (Draft 4 - 27/01/15) SCENE 1.INTRO. SFX SPACEY FX/MUSIC ANNOUNCER The following drama is based on the true story of Patrick Moore and the making of ‘The Sky At Night’. PATRICK MOORE (OLDER) All true, even the stuff I exaggerated to jolly up the proceedings. However, I do apologise for my restraint on more colourful opinions: PC-brigade, female producers, Europhiles and all that. Damn irritating.. (FADE) SFX SPACEY MUSIC – MIX TO – RADIO DIAL REWINDING BACK IN TIME TO: SCENE 2.INT. BBC STUDIO. 1957 ARCHIVE (OR MOCK-UP) CYRIL STAPLETON’S PARADE MUSIC PLAYS PAUL JOHNSTONE ..Countdown to live in 90..Ident, please.. STUDIO FM (ON TALKBACK) Sky At Night. Programme 1. 24/4/57. 10.30pm. Transmission, do you have a feed? TRANSMISSION CONTROL (ON TALKBACK) Hello, studio. Rolling credits on ‘Cyril Stapleton Parade’. I see your slate: (READS) ‘Producer, Paul Johnstone. Host, Patrick Meere.’ STUDIO FM (ON TALKBACK) ‘Moore’. TRANSMISSION CONTROL Correction, ‘Moore’. STUDIO FM (ON TALKBACK) Live in 60. -

Darrol Blake Transcript

Interview with Darrol Blake by Dave Welsh on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010 Dave Welsh: Okay, this is an interview with Darrol Blake on Tuesday the 21st of September 2010, for the Britain at Work Project, West London, West Middlesex. Darrol, I wonder if you'd mind starting by saying how you got into this whole business. Darrol Blake: Well, I'd always wanted to be the man who made the shows, be it for theatre or film or whatever, and this I decided about the age of eleven or twelve I suppose, and at that time I happened to win a scholarship to grammar school, in West London, in Hanwell, and formed my own company within the school, I was in school plays and all that sort of thing, so my life revolved around putting on shows. Nobody in my family had ever been to university, so I assumed that when I got to sixteen I was going out to work. I didn't even assume I would go into the sixth form or anything. So when I did get to sixteen I wrote around to all the various places that I thought might employ me. Ealing Studios were going strong at that time, Harrow Coliseum had a rep. The theatre at home in Hayes closed on me. I applied for a job at Windsor Rep, and quite by the way applied to the BBC, and the only people who replied were the BBC, and they said we have vacancies for postroom boys, office messengers, and Radio Times clerks. -

CN Summer 2007

_____________________________________________________________________ Current Notes The Journal of the Manchester Astronomical Society August 2007 _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Contents Page Obituary 1 Letters and News 1 The Sky at Night 2 By Kevin J Kilburn Some Open Star Clusters in our Winter Skies 4 By Cliff Meredith Picture Gallery 7-10 Balmer 11 By Nigel Longshaw The Total Lunar Eclipse 12 By Anthony Jennings The Occultation of Saturn 12 By Kevin J Kilburn Global Warming Propaganda and ‘The Chilling Stars’ 13–15 By Guy Duckworth _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Obituary being re-elected in 1987 and 1988. In accordance with MAS rules, upon his John Bolton joined the Manchester retirement as President he served as Astronomical Society (MAS) sometime during Immediate Past President under the presidency the summer of 1967, although it was not until of Ray Brierley until the election of Kevin the General Meeting in October of that year Kilburn as President in 1991 when John took that his membership was recorded in the MAS on the office of Vice President. There were four Register of Members. Vice Presidents in the MAS at this time in its history. This structure continued until 1996 when the management of the MAS underwent radical change and the number of council posts was reduced to a total of 10 with three of the Vice President positions being abolished along with the re-classification of others. At the Annual General Meeting (AGM) in 1996, John was elected to the sole remaining post of Vice President and continued in this capacity until the AGM in April 2007. Throughout his almost 40 years of membership, John’s enthusiasm was infectious and many current members owe much to his passion for astronomy. -

View Print Program (Pdf)

PROGRAM November 3 - 5, 2016 Hosted by Sigma Pi Sigma, the physics honor society 2016 Quadrennial Physics Congress (PhysCon) 1 31 Our students are creating the future. They have big, bold ideas and they come to Florida Polytechnic University looking for ways to make their visions a reality. Are you the next? When you come to Florida Poly, you’ll be welcomed by students and 3D faculty who share your passion for pushing the boundaries of science, PRINTERS technology, engineering and math (STEM). Florida’s newest state university offers small classes and professors who work side-by-side with students on real-world projects in some of the most advanced technology labs available, so the possibilities are endless. FLPOLY.ORG 2 2016 Quadrennial Physics Congress (PhysCon) Contents Welcome ........................................................................................................................... 4 Unifying Fields: Science Driving Innovation .......................................................................... 7 Daily Schedules ............................................................................................................. 9-11 PhysCon Sponsors .............................................................................................................12 Planning Committee & Staff ................................................................................................13 About the Society of Physics Students and Sigma Pi Sigma ���������������������������������������������������13 Previous Sigma Pi Sigma -

Brian May Plays “God Save the Queen” from the Roof of Buckingham Palace to Commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’S Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002

Exclusive interview Brian May plays “God Save the Queen” from the roof of Buckingham Palace to commemorate Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee on June 3, 2002. © 2002 Arthur Edwards 26 Astronomy • September 2012 As a teenager, Brian Harold May was shy, uncer- tain, insecure. “I used to think, ‘My God, I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to wear, I don’t know who I am,’ ” he says. For a kid who didn’t know who he was or what he wanted, he had quite a future in store. Deep, abiding interests and worldwide success A life in would come on several levels, from both science and music. Like all teenagers beset by angst, it was just a matter of sorting it all out. Skiffle, stars, and 3-D A postwar baby, Brian May was born July 19, 1947. In his boyhood home on Walsham Road in Feltham on the western side of Lon- science don, England, he was an only child, the offspring of Harold, an electronics engineer and senior draftsman at the Ministry of Avia- tion, and Ruth. (Harold had served as a radio operator during World War II.) The seeds for all of May’s enduring interests came early: At age 6, Brian learned a few chords on the ukulele from his father, who was a music enthusiast. A year later, he awoke one morning to find a “Spanish guitar hanging off the end of my bed.” and At age 7, he commenced piano lessons and began playing guitar with enthusiasm, and his father’s engineering genius came in handy to fix up and repair equipment, as the family had what some called a modest income. -

HP0181 Nancy Thomas

Nancy Tbomas DRAFT Page 1 This recording was transcribed by funds from the AHRC-funded ‘History of Women in British Film and Television project, 1933-1989’, led by Dr Melanie Bell (Principal Investigator, University of Leeds) and Dr Vicky Ball (Co-Investigator, De Montfort University). (2015). BECTU History Project Interview no: 181 Interviewee: Nancy Thomas Interviewer: Norman Swallow/Alan Lawson [NB: Identities not clear] Duration: 02:24:07 The copyright of this recording is vested in the ACTT History Project. Nancy Thomas, television producer/director. Interviewer Norman Swallow. Recorded on the twenty-fifth of January 1991. Well, if you don’t mind, you know, when and where were you born? I was born in India in 1918. Where? I was born in a little place called Ranikhet, partly because, you know, pregnant mums from… my father was in the Indian Army and they were all moved into the hills, so I was born in the foothills of the Himalayas. And what about schooling? Well, I came home because my mother taught me to read and write and that was quite interesting, because I’m left-handed and she didn’t think that they’d let me write with my right hand, so she made me write with my right hand. And we had frightful rows, she said, terrible rows. But I was reading, you see, by about the age of four and was then sent home, brought home, when I was six and lodged with an aunt and cousins. So I was really brought up by my aunt and cousins in Berkhamsted, and I went to school at Berkhamsted School for Girls. -

|FREE| Film Genre for the Screenwriter

FILM GENRE FOR THE SCREENWRITER EBOOK Author: Jule Selbo Number of Pages: 339 pages Published Date: 07 Aug 2014 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Ltd Publication Country: London, United Kingdom Language: English ISBN: 9781138020832 Download Link: CLICK HERE Film Genre For The Screenwriter Online Read Please Film Genre for the Screenwriter it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Writers Store. Film genres may appear to be readily categorizable from the setting of the film. A screenwriter becomes credible by having work that is recognized, which gives the writer the opportunity to earn a higher income. Should they be prepared to be scared? Are genres culture-bound or trans-cultural? An example would be writing a horror film where a young woman is getting chased by a stranger down a dark alley and finally gets cornered by him. Wikimedia Commons. Subscription or UK public library membership required. New York: Focal Press. Be amazed? When word is put out about a project a film studioproduction companyor producer wants done, they are Film Genre for the Screenwriter to as "open" assignments. So when watching and analyzing film genres we must remember to remember its true intentions aside from its entertainment value. Lists of films by genre and themes. Reviews Film Genre For The Screenwriter Central apparatus room Changing room Master control room Network operations center Production control room Stage theatre Transmission control room. Maybe Stage 32 just kept you in the game?! Format refers to the way the film was shot e. For example, while both The Battle of Midway and All Film Genre for the Screenwriter on the Film Genre for the Screenwriter Front are set in a wartime context and might be classified as belonging to the war film genre, the first examines the themes of honor, sacrifice, and valour, and the second is an anti-war film which emphasizes the pain and horror of war. -

Number 42 Michaelmas 2018

Number 42 Michaelmas 2018 Number 42 Michaelmas Term 2018 Published by the OXFORD DOCTOR WHO SOCIETY [email protected] Contents 4 The Time of Doctor Puppet: interview with Alisa Stern J A 9 At Last, the Universe is Calling G H 11 “I Can Hear the Sound of Empires Toppling’ : Deafness and Doctor Who S S 14 Summer of ‘65 A K 17 The Barbara Wright Stuff S I 19 Tonight, I should liveblog… G H 22 Love Letters to Doctor Who: the 2018 Target novelizations R C 27 Top or Flop? Kill the Moon J A, W S S S 32 Haiku for Kill the Moon W S 33 Limerick for Kill the Moon J A 34 Utopia 2018 reports J A 40 Past and present mixed up: The Time Warrior M K 46 Doctors Assemble: Marvel Comics and Doctor Who J A 50 The Fan Show: Peter Capaldi at LFCC 2018 I B 51 Empty Pockets, Empty Shelves M K 52 Blind drunk at Sainsbury’s: Big Finish’s Exile J A 54 Fiction: A Stone’s Throw, Part Four J S 60 This Mid Curiosity: Time And Relative Dimensions In Shitposting W S Front cover illustration by Matthew Kilburn, based on a shot from The Ghost Monument, with a background from Following Me Home by Chris Chabot, https://flic.kr/p/i6NnZr, (CC BY-NC 2.0) Edited by James Ashworth and Matthew Kilburn Editorial address [email protected] Thanks to Alisa Stern and Sophie Iles This issue was largely typeset in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro by Adobe; members of the Alegreya family, designed by Juan Pablo del Peral; members of the Saira family by Omnibus Type; with Arial Rounded MT Bold, Baskerville, Bauhaus 93, and Gotham Narrow Black. -

Patrick Moore Become an Iconic Symbol of Sir Patrick Moore in with Countless Books and a 55-Year-Old Monthly TV Program, Britain’S Astronomy Community

A knight’s tale To step inside Moore’s house in Selsey, England, Visiting Britain’s legendary is to walk through decades of astronomical Pete Lawrence Pete The weather vane at his home in Selsey has history. Patrick Moore become an iconic symbol of Sir Patrick Moore in With countless books and a 55-year-old monthly TV program, Britain’s astronomy community. Sir Patrick Moore is synonymous with the wonders of the cosmos and British eccentricity. by Stuart Clark Of cats and planets sound-bite sentences and uttered with a dry To step inside Moore’s house in Selsey, Eng- sense of old English humor. Although the land, is to walk through decades of astro- voice is quieter now, and occasionally a little nomical history. Everywhere you look, tremulous, his delivery is unmistakable. books, photos, or other memorabilia com- He points to the mantelpiece, where memorate a lifetime of astronomical work. carved bookends hold together a collection f you have ever seen the televi- Before going inside, though, first you see of small blue books. “One of those is called Patrick Moore and the BBC premiered The Sky sion program, you would be a handwritten sign on the front door. It The Story of the Solar System by G. F. at Night in April 1957. The broadcast company forgiven for thinking Sir explains that cats live in the house, so the Chambers,” Moore explains. “I picked that originally slated the monthly program for three porch door and the front door must never up when I was 6 and read it through, and I episodes to see how viewers would receive it; it has been running continuously in mostly the Patrick Moore delivered be open at the same time, lest they escape. -

Delivering Quality First – Page 2

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel A future plan Delivering Quality First – Page 2 Photo courtesy of Jeff Overs November 2011 • Issue 8 tales of Print edition of Musical televison ariel to close memories Centre Page 2 Page 6 Page 9 NEWS • MEMoriES • ClaSSifiEdS • Your lEttErS • obituariES • CroSPEro 02 uPdatE froM thE bbC commissioning and scheduling will be • More landmark output for Radio 4 (which closely aligned. sees its overall budget hardly changed). Delivering Quality First • Job grading, redundancy terms and • More money for the Proms. unpredictability allowances will be • The further rollout of HD and DAB. Mark Thompson sets out ‘a plan for living within our means’ as ‘modernised’ and reformed. A consultation he reveals job losses, output changes, relocations, structured process on those proposals begins Union response immediately. The National Union of Journalists issued a re-investment in a digital public space, and new content and • Production will be streamlined into a swift response to the announcement, calling programmes on BBC services. single UK production economy. for the licence fee negotiations to be re- • Radio and TV commissioning for Science opened and ‘a proper public debate about Fewer staff, a flatter structure, more jobs • All new daytime programming will be and Music will be brought together. BBC funding’. shifting to Salford and more output from on BBC One. In a statement the NUJ said: ‘The BBC will outside London, these are the conclusions of • BBC Two’s daytime output will focus on Reinvestment not be the same organisation if these cuts go the Delivering Quality First process. -

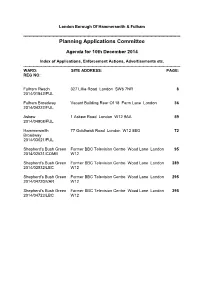

Planning Applications Committee

London Borough Of Hammersmith & Fulham --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Planning Applications Committee Agenda for 10th December 2014 Index of Applications, Enforcement Actions, Advertisements etc. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- WARD: SITE ADDRESS: PAGE: REG NO: Fulham Reach 327 Lillie Road London SW6 7NR 8 2014/01842/FUL Fulham Broadway Vacant Building Rear Of 18 Farm Lane London 36 2014/04222/FUL Askew 1 Askew Road London W12 9AA 59 2014/04908/FUL Hammersmith 77 Goldhawk Road London W12 8EG 72 Broadway 2014/03021/FUL Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 95 2014/02531/COMB W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 289 2014/02532/LBC W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 295 2014/04720/VAR W12 Shepherd's Bush Green Former BBC Television Centre Wood Lane London 395 2014/04723/LBC W12 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ward: Fulham Reach Site Address: 327 Lillie Road London SW6 7NR © Crown Copyright. All Rights Reserved. London Borough Hammersmith and Fulham LA100019223 (2013). For identification purposes only - do not scale. Reg. No: Case Officer: 2014/01842/FUL Roy Asagba-Power Date Valid: Conservation Area: 23.04.2014 Committee Date: 10.12.2014 Applicant: Mr Ashok Patel 35/37 Ludgate Hill London EC4M 7JN Description: Demolition of existing office buildings (Class B1) and the erection of 8 x two storey plus- basement single family dwelling houses (Class C3) with roof terraces at first floor level; formation of refuse and cycle storage; installation of two new access gates fronting Lillie Road elevation; replacement of existing power sub-station and formation of a new underground power sub-station in between properties 17-20 and 337 Lillie Road. -

Odyssey 21 November 2012

OdyIsssue 2s2, Deceembey r 2012 Image courtesy of NASA/JPL The e-Magazine of the British Interplanetary Society From Super Constellations , Dakotas and In This Issue l Super Constellations, Dakotas, and Comets to HOTOL and SKYLON Comets to HOTOL and SKYLON Titans of the BIS: Ken Gatland The Society’s new President, Alistair Scott, programme was of course The Sky at Night . I l talks to Odyssey about the path that subsequently discovered that the 6 inch l Imagining Outer Space led him to join the BIS, and his vision for telescope was his too, left by him when in l The Feedback Loop the future. 1955 or 56 he handed over his position as l Crafting the Future Why did I join the British Interplanetary Head of Science to my House Master, and Society ? I’ve never been asked that before. started working with the BBC. l The Odyssey Essay File The simple answer would be, because it was I wasn’t so turned on by astronomy and l Echoes from the Future there when I needed it. space at that point. I was far more l Dates for Your Diary So where do I start? I suppose I should go interested in the aircraft - the Super right back to when I was seven. I and my Constellations , Dakotas , Comets and later the brother were sent back from Bangkok to Boeing 707 s -that flew me to and from the boarding school in Kent. Far East each summer holiday. I didn’t really In Next Month’s Issue want to fly them - I wanted to know how l Leading SF author David Brin steps they worked and why they flew! So after a into the Virtual Interview Chair further 5 years at school, this time at my father’s old school in Scotland, I applied to l John Silvester reviews 2132 , Kim join the Undergraduate Apprentice Scheme Stanley Robinson’s latest epic novel at Hawker Siddeley Aviation , Hatfield, and l And we continue to remember author, the Aeronautical Engineering course at spaceflight innovator and past BIS Bristol University.