Georgette Heyer, History and Historical Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph Mcgrath in 1969

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 6th April 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 The Magic Christian on Talking Pictures TV Directed by Joseph McGrath in 1969. Stars: Peter Sellers and Ringo Starr, with appearances by Raquel Welch, John Cleese, Graham Chapman, Spike Milligan, Christopher Lee, Richard Attenborough and Roman Polanski. Sir Guy Grand is the richest man in the world, and when he stumbles across a young orphan in the park he decides to adopt him and travel around the world spending cash. It’s not long before the two of them discover on their happy-go-lucky madcap escapades that money does, in fact, buy anything you want. Airs on Saturday 11th April at 9pm Monday 6th April 08:55am Wednesday 8th April 3:45pm Thunder Rock (1942) Heart of a Child (1958) Supernatural drama directed by Roy Drama, directed by Clive Donner. Boulting. Stars: Michael Redgrave, Stars: Jean Anderson, Barbara Mullen and James Mason. Donald Pleasence, Richard Williams. One of the Boulting Brothers’ finest, A young boy is forced to sell the a writer disillusioned by the threat of family dog to pay for food. Will his fascism becomes a lighthouse keeper. canine friend find him when he is trapped in a snowstorm? Monday 6th April 10pm The Family Way (1966) Wednesday 8th April 6:20pm Drama. Directors: Rebecca (1940) Roy and John Boulting. Mystery, directed by Alfred Hitchcock Stars: Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett and starring Laurence Olivier, John Mills and Marjorie Rhodes. Joan Fontaine and George Sanders. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

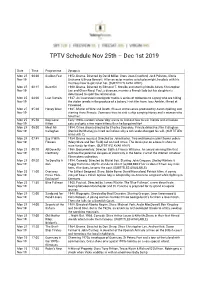

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

THE NOVELS and the POETRY of PHILIP LARKIN by JOAN SHEILA MAYNE B . a . , U N I V E R S I T Y of H U L L , 1962 a THESIS SUBMITT

THE NOVELS AND THE POETRY OF PHILIP LARKIN by JOAN SHEILA MAYNE B.A., University of Hull, 1962 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF M .A. in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1968 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his represen• tatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of English The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada April 26, 1968 ii THESIS ABSTRACT Philip Larkin has been considered primarily in terms of his contribution to the Movement of the Fifties; this thesis considers Larkin as an artist in his own right. His novels, Jill and A Girl in Winter, and his first volume of poetry, The North Ship, have received very little critical attention. Larkin's last two volumes of poetry, The Less Deceived and The Whitsun Weddings, have been considered as two very similar works with little or no relation to his earlier work. This thesis is an attempt to demonstrate that there is a very clear line of development running through Larkin's work, in which the novels play as important a part as the poetry. -

Saturday, July 7, 2018 | 15 | WATCH Monday, July 9

6$785'$<-8/< 7+,6,6123,&1,& _ )22' ,16,'( 7+,6 :((. 6+233,1* :,1(6 1$',<$ %5($.6 &KHFNRXW WKH EHVW LQ ERWWOH 683(50$5.(7 %(67 %8<6 *UDE WKH ODWHVW GHDOV 75,(' $1' 7(67(' $// 7+( 58/(6 :H FKHFN RXW WRS WUDYHO 1$',<$ +XVVDLQ LV D KDLUGU\HUV WR ORRN ZDQWDQGWKDW©VZK\,IHHOVR \RXGRQ©WHDWZKDW\RX©UHJLYHQ WRWDO UXOHEUHDNHU OXFN\§ WKHQ \RX JR WR EHG KXQJU\§ JRRG RQ WKH PRYH WKHVH GD\V ¦,©P D 6KH©V ZRQ 7KLV UHFLSH FROOHFWLRQ DOVR VHHV /XFNLO\ VKH DQG KXVEDQG $EGDO SDUW RI WZR YHU\ %DNH 2II SXW KHU IOLS D EDNHG FKHHVHFDNH KDYH PDQDJHG WR SURGXFH RXW D VOHZ RI XSVLGH GRZQ PDNH D VLQJOH FKLOGUHQ WKDW DUHQ©W IXVV\HDWHUV GLIIHUHQW ZRUOGV ¤ ,©P %ULWLVK HFODLU LQWR D FRORVVDO FDNH\UROO VR PXFK VR WKDW WKH ZHHN EHIRUH 5(/$; DQG ,©P %DQJODGHVKL§ WKH FRRNERRNV DQG LV DOZD\V LQYHQW D ILVK ILQJHU ODVDJQH ZH FKDW VKH KDG DOO WKUHH *$0(6 $336 \HDUROG H[SODLQV ¦DQG UHDOO\ VZDS WKH SUDZQ LQ EHJJLQJ KHU WR GROH RXW IUDJUDQW &RQMXUH XS RQ WKH WHOO\ ¤ SUDZQ WRDVW IRU FKLFNHQ DQG ERZOIXOV RI ILVK KHDG FXUU\ EHFDXVH ,©P SDUW RI WKHVH 1DGL\D +XVVDLQ PDJLFDO DWPRVSKHUH WZR DPD]LQJ ZRUOGV , KDYH ¦VSLNH§ D GLVK RI PDFDURQL ¦7KH\ ZHUH DOO RYHU LW OLNH WHOOV (//$ FKHHVH ZLWK SLFFDOLOOL ¤ WKH ¨0XPP\ 3OHDVH FDQ ZH KDYH 086,& QR UXOHV DQG QR UHVWULFWLRQV§ :$/.(5 WKDW 5(/($6(6 ZRPDQ©V D PDYHULFN WKDW ULJKW QRZ"© , ZDV OLNH ¨1R +HQFH ZK\ WKUHH \HDUV RQ IURP IRRG LV PHDQW +RZHYHU KHU DSSURDFK WR WKDW©V WRPRUURZ©V GLQQHU ,©YH :H OLVWHQ WR WKH ZLQQLQJ *UHDW %ULWLVK %DNH 2II WR EH IXQ FODVKLQJDQG PL[LQJ IODYRXUVDQG MXVW FRRNHG LW HDUO\ \RX©YH JRW ODWHVW DOEXPV WKH /XWRQERUQ -

1. ABBOT, Gorham D. Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual

1. ABBOT, Gorham D . Mexico, and the United States; Their Mutual Relations and Common Interests . Illustrated with two steel- engraved portraits and one folding, colored map by Colton of Mexico and much of Texas and the Southwest. 8vo, New York: G. P. Putnam & Son, 1869. First edition. Original green cloth gilt. An impeccable, fresh copy, inscribed by the author on the title page. Bookplate adhering to flyleaf. $1,500 A key early work on the history of U.S.-Mexican relations, with portraits of Juarez and Romero, and a detailed and beautifully colored map of Mexico (17 ½ x 25 ¾ inches). Inscribed on the title page, “J W Hamersley Esq | with the respects of | Gorham D. Abbot.” ’ 2. ANDREWS, Roy Chapman . The New Conquest of Central Asia. A Narrative of the Explorations of the Central Asiatic Expeditions in Mongolia and China, 1921-1930 . The Natural History of Central Asia vol. I, Chester A. Reed, editor. With chapters by Walter Granger … Clifford H. Pope … Nels C. Nelson … with 128 plates and 12 illustrations in the text and 3 maps at end. lx, 678pp. 4to, New York: The American Museum of Natural History, 1932. First edition. Publisher’s orange cloth stamped in black. Minor wear at extremities. Archival repair to pp. 335-6. An attractive and extremely desirable copy. In custom black morocco-backed slipcase with inner wrapper. Yakushi A 223. $4,500 The New Conquest of Central Asia is a lavishly produced volume that stands as one of the landmarks of twentieth-century exploration. This copy is from the library of the author, Roy Chapman Andrews. -

Report to the U. S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2003

Report to the U.S.Congress for the Year Ending December 31,2003 Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage April 30, 2004 Dr. James H. Billington The Librarian of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540-1000 Dear Dr. Billington: In accordance with Public Law 104-285 (Title II), The National Film Preservation Foundation Act of 1996, I submit to the U.S. Congress the 2003 Report of the National Film Preservation Foundation. It gives me great pleasure to review our accomplishments in carrying out this Congressional mandate. Since commencing service to the archival community in 1997, we have helped save 630 historically and culturally significant films from 98 institutions across 34 states and the District of Columbia. We have produced The Film Preservation Guide: The Basics for Archives, Libraries, and Museums, the first such publication designed specifically for regional preservationists, and have pioneered in pre- senting archival films on widely distributed DVDs and on American television. Unseen for decades, motion pictures preserved through our programs are now extensively used in study and exhibition. There is still much to do. This year Congress will consider the reauthorization of our federal grant programs. Increased funding will enable us to expand service to the nation’s archives, libraries, and museums and do more toward saving America’s film heritage for future generations. The film preser- vation community appreciates your efforts to make the case for increased federal investment. We are deeply grateful for your leadership. Space does not permit my acknowledging all those supporting our efforts in 2003, but I would like to single out several organizations that have played an especially significant role: the National Endowment for the Humanities, The Andrew W. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 27 January – 2 February 2018 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 27 January – 2 February 2018 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 27 JANUARY 2018 Series 3, Episode 2Gyles Brandreth chairs the scandals quiz Jan Ravens and guests chart the journey of changing attitudes to with Anthony Holden, Lucy Moore, Richard Herring and female satire. Recorded with an audience in the BBC Radio SAT 00:00 The Scarifyers (b007wv3h) Louise Doughty. From October 2005. Theatre of Broadcasting House in London. The Thirteen Hallows, Episode 4Professor Dunning and his SAT 04:30 After Henry (b007jnzw) Ever since Donald Trump dubbed Hillary Clinton a 'nasty knightly friend Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr are captured and taken to Series 2, The TeapotEleanor wants a video player but how can woman' during a presidential debate, women the world over King Arthur's final resting place: Barry Island, in Wales. With she raise the cash?. have embraced the term as a battle-cry and responded not only shadowy forces both home and abroad ranged against them, can Simon Brett's comedy about three generations of women - with a viral campaign on social media but with Nasty Woman T- Harry Crow and the mysterious Mr Merriman save them? struggling to cope after the death of Sarah's GP husband - who shirts, perfumes and cocktails. This spirited response chimes The Scarifyers follows the exploits of 1930s ghost-story writer never quite manage to see eye to eye. with a long tradition of feisty female comedians on the radio. Professor Dunning and retired policeman Harry Crow, who Starring Prunella Scales as Sarah, Joan Sanderson as Eleanor, In a sometimes frank discussion, Jan and her guests - Kiri together investigate weird mysteries under the auspices of top- Benjamin Whitrow as Russell, Gerry Cowper as Clare and Pritchard-McLean, Lauren Pattison and the BBC's radio secret government department MI:13. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 360 972 IR 054 650 TITLE More Mysteries. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington,D.C. National Library Service for the Blind andPhysically Handicapped. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0763-1 PUB DATE 92 NOTE 172p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Audiodisks; *Audiotape Recordings; Authors; *Blindness; *Braille;Government Libraries; Large Type Materials; NonprintMedia; *Novels; *Short Stories; *TalkingBooks IDENTIFIERS *Detective Stories; Library ofCongress; *Mysteries (Literature) ABSTRACT This document is a guide to selecteddetective and mystery stories produced after thepublication of the 1982 bibliography "Mysteries." All books listedare available on cassette or in braille in the network library collectionsprovided by the National Library Service for theBlind and Physically Handicapped of the Library of Congress. In additionto this largn-print edition, the bibliography is availableon disc and braille formats. This edition contains approximately 700 titles availableon cassette and in braille, while the disc edition listsonly cassettes, and the braille edition, only braille. Books availableon flexible disk are cited at the end of the annotation of thecassette version. The bibliography is divided into 2 Prol;fic Authorssection, for authors with more than six titles listed, and OtherAuthors section, a short stories section and a section for multiple authors. Each citation containsa short summary of the plot. An order formfor the cited -

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May

APPENDIX ALCOTT, Louisa May. American. Born in Germantown, Pennsylvania, 29 November 1832; daughter of the philosopher Amos Bronson Alcott. Educated at home, with instruction from Thoreau, Emerson, and Theodore Parker. Teacher; army nurse during the Civil War; seamstress; domestic servant. Edited the children's magazine Merry's Museum in the 1860's. Died 6 March 1888. PUBLICATIONS FOR CHILDREN Fiction Flower Fables. Boston, Briggs, 1855. The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale. Boston, Redpath, 1864. Morning-Glories and Other Stories, illustrated by Elizabeth Greene. New York, Carleton, 1867. Three Proverb Stories. Boston. Loring, 1868. Kitty's Class Day. Boston, Loring, 1868. Aunt Kipp. Boston, Loring, 1868. Psyche's Art. Boston, Loring, 1868. Little Women; or, Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy, illustrated by Mary Alcott. Boston. Roberts. 2 vols., 1868-69; as Little Women and Good Wives, London, Sampson Low, 2 vols .. 1871. An Old-Fashioned Girl. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low, 1870. Will's Wonder Book. Boston, Fuller, 1870. Little Men: Life at Pluff?field with Jo 's Boys. Boston, Roberts, and London. Sampson Low, 1871. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag: My Boys, Shawl-Straps, Cupid and Chow-Chow, My Girls, Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, An Old-Fashioned Thanksgiving. Boston. Roberts. and London, Sampson Low, 6 vols., 1872-82. Eight Cousins; or, The Aunt-Hill. Boston, Roberts, and London, Sampson Low. 1875. Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to "Eight Cousins." Boston, Roberts, 1876. Under the Lilacs. London, Sampson Low, 1877; Boston, Roberts, 1878. Meadow Blossoms. New York, Crowell, 1879. Water Cresses. New York, Crowell, 1879. Jack and Jill: A Village Story. -

9781596437081EX.Pdf

INTRODUCTION In October of 2010 the Children’s Book- a-Day Almanac website was launched (chil drensbookalmanac.com); each day since then one essay showcasing one of the gems of children’s literature has been published. Day after day I have been able to connect with readers— to lead them to books that they need and to remind them of the books that have made a difference in the lives of children. I have responded to ques- tions and critiques. I have also had children comment on the Almanac, through their parents and teachers, to inform me how they felt about my choices. All critics need to keep in touch with what happens when the rubber meets the road! As I prepared the fi nal pages for the printed book, I kept thinking about how much my daily Almanac readers have made it a better resource. Although I love the immediacy of cyberspace, I am thrilled to have this book in print. Now readers can easily thumb through and make plans for celebrating their own favorite days in advance. Every day of the calendar year I discuss an appropriate title and then provide information about how it came about, the author, the ideal au- dience, and how the book has connected in a meaningful way with young people from babies to age fourteen. For 365 days—or with a leap year 366—I provide a reli- able guide to the classics and to new books on their way to becoming classics. On March 12 I talk about Madeleine L’Engle’s road from rejection to her award-winning book A Wrinkle in Time; on June 11 I relate how Hans and Margret Rey saved Cu- rious George and themselves from the Nazis; on July 18 I focus on the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and its impact on Munro Leaf’s The Story of Ferdinand. -

Gentle Romances, 2014

ISBN 978-0-8444-9569-9 Gentle 2014 Romances National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped Washington 2014 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. Gentle romances, 2014. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978-0-8444-9569-9 1. Blind--Books and reading--Bibliography--Catalogs. 2. Talking books-- Bibliography--Catalogs. 3. Braille books--Bibliography--Catalogs. 4. Love stories-- Bibliography--Catalogs. 5. Library of Congress. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped--Catalogs. I. Title. Z5347.L533 2014 [HV1721] 016.823’08508--dc23 2014037860 Contents Introduction .......................................... iii pense, or paranormal events may be present, Audio ..................................................... 1 but the focus is on the relationship. Dull, Braille .................................................... 41 everyday problems tend to be glossed over Index ...................................................... 53 and, although danger may be imminent, the Audio by author .................................. 53 environment is safe for the main characters. Audio by title ...................................... 61 Much of modern fiction—romances in- Braille by author ................................. 71 cluded—contains strong language and Braille by title ..................................... 73 descriptions of sex and violence. But not Order Forms ........................................