The University of Liverpool the REPRESENTATION OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arnold Wesker'ın Chicken Soup with Barley

Atatürk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 2011 15 (2): 133-145 The Legacy of Communist Idealism Contested in Chicken Soup with Barley by Arnold Wesker: Political Imperative upon the Personal and Subverted Binary Opposites Erdinç PARLAK (*) Abstract: A dramatic dismantling will surely show that Arnold Wesker’s early plays represent the most amiable contestation of the New Left and the new conditions with the surprising yet desired success of the Labour. In early post-war years, Britons anachronistically hold the myth of the long Edwardian summer and thus reconnect with peace after the Great Wars. Unfortunately, though, the repressed memories of Wars haunt the writings and the aura of the age. That’s why in Wesker’s accounts, especially in his early corpus, Wars work double shift reminding us the hopes of the new generation and their disillusionment after the failure of the Labour. With this background in mind, our study tries to enlarge the theme of communist idealism and disappointment contested in Wesker’s Chicken Soup with Barley. In this play, an angry young man through and through and a representative playwright of the first wave in post-war British drama, Arnold Wesker poignantly shows how politics works as an imperative upon the private and the personal and it is also the sexual politics that Wesker contests and subverts. These two issues further serve for his handling of ethnicity (Anglo-Jewry), class (proletariat) and gender (binary opposition). Key Words: Arnold Wesker, communist idealism, subverted binary opposites, sexual politics, Anglo-Jewry, proletariat Arnold Wesker’ın Chicken Soup With Barley (Arpalı Tavuk Çorbası) Oyununda Komünist İdealizm Mirası: Birey Üzerindeki Siyasi Zorunluluk ve Bozulan İkili Karşıtlıklar Özet: Dramatik bir çalışma Arnold Wesker’ın ilk oyunlarının, İşçi Partisi‘nin beklenen fakat şaşırtıcı başarısıyla gelen yeni dünya düzeni ve Yeni Sol hareketinin en hafif ve yumuşak tanıklığını gösterecektir. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Dominic Cooke Director

Dominic Cooke Director Film 2021 THE COURIER Feature film starring Benedict Cumberbatch 42/SunnyMarch World Premiere – Sundance Film Festival 2020 2017 ON CHESIL BEACH Feature film based on the novel by Ian McEwan BBC Films & Number 9 Films North American Premiere – Toronto International Film Festival 2017 Television 2016 THE HOLLOW CROWN 3 Episodes: Henry VI Part I, Henry VI Part II, Richard III BBC/ NBC Universal Television / Neal Street Productions / WNET Thirteen Theatre 2017 FOLLIES Written by Stephen Sondheim Royal National Theatre 10 Olivier Nominations including Best Director 2016 PIGS AND DOGS Written by Caryl Churchill Royal Court Theatre 2016 MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Written by August Wilson Royal National Theatre 1 Olivier Win 2015 HERE WE GO Written by Caryl Churchill Royal National Theatre 2015 TEDDY FERRERA Written by Christopher Shinn Donmar Warehouse 2013 THE LOW ROAD Written by Bruce Norris Royal Court Theatre 2013 IN THE REPUBLIC OF HAPPINESS Written by Martin Crimp Royal Court Theatre 2012 DING DONG THE WICKED Written by Caryl Churchill Royal Court Theatre 2012 CHOIR BOY Written by Tarell Alvin McCraney Royal Court Theatre 2012 IN BASILDON Written by David Eldridge Royal Court Theatre 2011 CHICKEN SOUP WITH BARLEY Written by Arnold Wesker Royal Court Theatre 2011 THE COMEDY OF ERRORS Written by William Shakespeare Royal National Theatre 2010 CLYBOURNE PARK Written by Bruce Norris Royal Court Theatre 1 Olivier Win 2009 AUNT DAN AND LEMON Written by Wallace Shawn Royal Court Theatre 2009 THE FEVER Written by Wallace Shawn Royal Court Theatre 2009 SEVEN JEWISH CHILDREN Written by Caryl Churchill Royal Court Theatre 2008 WIG OUT! Written by Tarell Alvin McCraney Royal Court Theatre 2008 NOUGHTS AND CROSSES Director & Writer. -

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein THEATER 17/18 FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. any day of the week. -

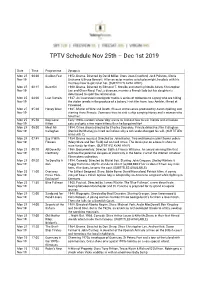

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

The Nation's Matron: Hattie Jacques and British Post-War Popular Culture

The Nation’s Matron: Hattie Jacques and British post-war popular culture Estella Tincknell Abstract: Hattie Jacques was a key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, condensing a range of contradictions around power, desire, femininity and class through her performances as a comedienne, primarily in the Carry On series of films between 1958 and 1973. Her recurrent casting as ‘Matron’ in five of the hospital-set films in the series has fixed Jacques within the British popular imagination as an archetypal figure. The contested discourses around nursing and the centrality of the NHS to British post-war politics, culture and identity, are explored here in relation to Jacques’s complex star meanings as a ‘fat woman’, ‘spinster’ and authority figure within British popular comedy broadly and the Carry On films specifically. The article argues that Jacques’s star meanings have contributed to nostalgia for a supposedly more equitable society symbolised by socialised medicine and the feminine authority of the matron. Keywords: Hattie Jacques; Matron; Carry On films; ITMA; Hancock’s Half Hour; Sykes; star persona; post-war British cinema; British popular culture; transgression; carnivalesque; comedy; femininity; nursing; class; spinster. 1 Hattie Jacques (1922 – 1980) was a gifted comedienne and actor who is now largely remembered for her roles as an overweight, strict and often lovelorn ‘battle-axe’ in the British Carry On series of low- budget comedy films between 1958 and 1973. A key figure in British post-war popular cinema and culture, Hattie Jacques’s star meanings are condensed around the contradictions she articulated between power, desire, femininity and class. -

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Angry Young Men

University of Pardubice Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Angry Young Men in British Drama: Analysis and Comparison of The Entertainer and The Kitchen Bachelor Thesis 2020 Karolína Jeníčková Prohlašuji: Tuto práci jsem vypracovala samostatně. Veškeré literární prameny a informace, které jsem v práci využila, jsou uvedeny v seznamu použité literatury. Byla jsem seznámena s tím, že se na moji práci vztahují práva a povinnosti vyplývající ze zákona č. 121/2000 Sb., autorský zákon, zejména se skutečností, že Univerzita Pardubice má právo na uzavření licenční smlouvy o užití této práce jako školního díla podle § 60 odst. 1autorského zákona, a s tím, že pokud dojde k užití této práce mnou nebo bude poskytnuta licence o užití jinému subjektu, je Univerzita Pardubice oprávněna ode mne požadovat přiměřený příspěvek na úhradu nákladů, které na vytvoření díla vynaložila, a to podle okolností až do jejich skutečné výše. Beru na vědomí, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb., o vysokých školách a o změně a doplnění dalších zákonů (zákon o vysokých školách), ve znění pozdějších předpisů, a směrnicí Univerzity Pardubice č. 7/2019, bude práce zveřejněna v Univerzitní knihovně a prostřednictvím Digitální knihovny Univerzity Pardubice. V Pardubicích dne 14. 4. 2020 Karolína Jeníčková ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Mgr. Petra Kalavská, Ph.D., for her kindness and valuable advice during writing of this thesis. I would also like to thank my family for their support throughout my studies. ANNOTATION This bachelor thesis focuses on The Entertainer (1957) by John Osborne and on The Kitchen (1959) by Arnold Wesker, the plays written by playwrights referred to as the Angry Young Men. -

Document.Pdf

South Central offers impressive office space with a mix of contemporary and original features. South Central dates back to 1888 where it was originally a packing warehouse for John Stevenson & Sons Ltd called Central Buildings. Today South Central is the perfect mix of a contemporary work environment and period character. South Central is a particularly special building for Bruntwood, as it was actually the first acquisition the company made in Manchester city centre in 1979. This building is a unique example of how Manchester’s historical past has been transformed into a vibrant, modern and forward thinking home for business. Welcome to your new reception at South Central. The new reception scheme allows for co-working space, meeting space and collaboration between companies. At Bruntwood we encourage collaboration and creativity in the work place and are creating spaces to nurture this behaviour. SPACE DESIGNED 7,440 66 AROUND YOU SQ FT OF SPACE WORK STATIONS 1 4 2 This is an example layout of our 4th floor suite, measuring 7,440 sq ft. RECEPTION MEETING ROOMS MEETING BOOTHS 1 11 1 BREAK OUT SPACES SOFT SEATING AREAS TEA POINT Creative specification: Exposed features High ceilings Steel columns Wooden beams Open-plan suite Exposed air conditioning Raised-access flooring Pendant lighting EPC rating 81 (Band D) Building amenities include: On-site customer service team 24-hour building access DDA-compliant access Lift access x2 On-site restaurant and bar Connection speeds of up to 1GB per second Co-working space BLANK CANVAS OFFICE SPACE When it comes to your work space, But it’s not all about image. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced info the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on untii complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Summer 1998 National Sound Archive

THE BULLETIN OF THE NATIONAL SOUND ARCHIVE ‘playback’ PLAYBACK is the bulletin of the British Library National Sound Archive (NSA). It is published free of charge three playbacktimes a year, with information on the NSA's current and future activities, and news from the world of sound archives and audio PLAYBACK: Editor Alan Ward, manager Production PLAYBACK:Alan Editor Richard Fairman, Layout Liz Joseph preservation. Comments are welcome and should be addressed to the editor at the NSA. We have a special mailing list for PLAYBACK. Please write, phone, fax or e-mail us, or complete and send in the tear-off slip at the end of this issue (if you have not done so already) if you wish to receive future issues through the post. The National Sound Archive is one of the largest sound archives in the world and is based at the British Library’s new building at St. Pancras. For further information contact The British Library National Sound Archive 96 Euston Road, London NW1 2DB ISSN 0952-2360 Tel:0171-412 7440. Fax: 0171-412 7441 SUMMER 1998 e-mail: [email protected] Anna Kravchyshyn in her home in Slavsko, Ukraine, recorded by the NSA’s oral history section (photo Tim Smith, Bradford Heritage Recording Unit) NATIONAL SOUND ARCHIVE 19 what’s happening Bradford Industrial Museum, Moorside Road, Bradford BD2 3HP and most bookshops (Dewi Lewis Publishing, £13.95). ■ Major items from NSA collections now feature for the first time in the British Library’s permanent exhibitions, reopened ■ The NSA’s former HQ building at 29 Exhibition at St. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative.