Apuntesuniversitarios.Upeu.Edu.Pe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bright Typing Company

Tape Transcription Islam Lecture No. 1 Rule of Law Professor Ahmad Dallal ERIK JENSEN: Now, turning to the introduction of our distinguished lecturer this afternoon, Ahmad Dallal is a professor of Middle Eastern History at Stanford. He is no stranger to those of you within the Stanford community. Since September 11, 2002 [sic], Stanford has called on Professor Dallal countless times to provide a much deeper perspective on contemporary issues. Before joining Stanford's History Department in 2000, Professor Dallal taught at Yale and Smith College. Professor Dallal earned his Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University and his academic training and research covers the history of disciplines of learning in Muslim societies and early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. He is currently finishing a book-length comparative study of eighteenth century Islamic reforms. On a personal note, Ahmad has been terrifically helpful and supportive, as my teaching assistant extraordinaire, Shirin Sinnar, a third-year law student, and I developed this lecture series and seminar over these many months. Professor Dallal is a remarkable Stanford asset. Frederick the Great once said that one must understand the whole before one peers into its parts. Helping us to understand the whole is Professor Dallal's charge this afternoon. Professor Dallal will provide us with an overview of the historical development of Islamic law and may provide us with surprising insights into the relationship of Islam and Islamic law to the state and political authority. He assures us this lecture has not been delivered before. So without further ado, it is my absolute pleasure to turn over the podium to Professor Dallal. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

REFRAMING BORDERS: A STUDY OF THE VEIL, WRITING, AND REPRESENTATION OF THE FEMALE BODY IN THE PHOTO-BASED ARTWORK OF MONA HATOUM, SHIRIN NESHAT, AND LALLA ESSAYDI by MARYAM A M A ALWAZZAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Maryam A M A Alwazzan Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of the femaLe body In the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi This thesIs has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Master of Art HIstory degree in the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture by: Kate Mondloch ChaIr Derek Burdette Member MIchaeL Allan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018. II © 2018 Maryam A M A ALwazzan This work is lIcensed under a CreatIve Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. III THESIS ABSTRACT Maryam A M A ALwazzan Master of Arts Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture December 2018 Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of The Female Body In The Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi For a long tIme, most women beLIeved they had to choose between theIr MusLIm or Arab identIty and theIr beLIef in socIaL equaLIty of sexes. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

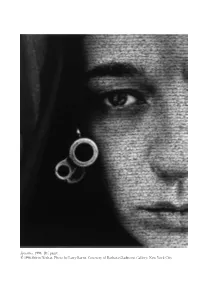

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 2 (2010) Jan W. Żelazny Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków The legend of Shirin in Syriac sources. A warning against caesaropapism? Why was Syriac Christianity not an imperial Church? Why did it not enter into a relationship with the authorities? This can be explained by pointing to the political situation of that community. I think that one of the reasons was bad experiences from the time of Chosroes II. The Story of Chosroes II The life of Chosroes II Parviz is a story of rise and fall. Although Chosroes II became later a symbol of the power of Persia and its ancient independence, he encountered numerous difficulties from the very moment he ascended the throne. Chosroes II took power in circumstances that today remain obscure – as it was frequently the case at the Persian court – and was raised to the throne by a coup. The rebel was inspired by an attempt of his father, Hormizd IV, to oust one of the generals, Bahram Cobin, which provoked a powerful reaction among the Persian aristocracy. The question concerning Chosroes II’s involvement in the conspiracy still remains unanswered; however, Chosroes II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father. Soon after, Hormizd IV died in prison in ambiguous circumstances. The Arabic historian, al-Tabari, claimed that Chosroes was oblivious of the rebellion. However, al-Tabari works were written several centuries later, at a time when the legend of the shah was already deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people. -

The False Caliph ROBERT G

The False Caliph ROBERT G. HAMPSON 1 heat or no heat, the windows have to be shut. nights like this, the wind winds down through the mountain passes and itches the skin on the backs of necks: anything can happen. 2 voices on the radio drop soundless as spring rain into the murmur of general conversation. his gloved hands tap lightly on the table-top as he whistles tunelessly to himself. his partner picks through a pack of cards, plucks out the jokers and lays down a mat face down in front of him. 285 286 The 'Arabian Nights' in English Literature the third hones his knife on the sole of his boot: tests its edge with his thumb. 3 Harry can't sleep. Mezz and the boys, night after night, have sought means to amuse him to cheat the time till dawn brings the tiredness that finally takes him. but tonight everything has failed. neither card-tricks nor knife-tricks - not even the prospect of nocturnal adventures down in the old town has lifted his gloom. they're completely at a loss. then the stranger enters: the same build the same face the same dress right down to the identical black leather gloves on the hands The False Caliph 287 which now tap contemptuously on the table while he whistles tunelessly as if to himself. Appendix W. F. Kirby's 'Comyarative Table of the Tales in the Principal Editions o the Thousand and One Nights' from fhe Burton Edition (1885). [List of editions] 1. Galland, 1704-7 2. Caussin de Perceval, 1806 3. -

Khosrow and Shirin Unknown Artist Nezami's… Abr Barani Art

www.sattor.com Khosrow & Shirin c. 1190 Nezami Ganjawi On lofty Beysitoun the lingering sun looks down on ceaseless labors, long begun: The mountain trembles to the echoing sound Of falling rocks, that from her sides rebound. Each day all respite, all repose denied--- No truce, no pause, the thundering strokes are plied; The mist of night around her summit coils, But still Ferhad, the lover-artist, toils, And still---the flashes of his axe between--- He sighs to ev'ry wind, "Alas! Shirin! Alas! Shirin!---my task is well-nigh done, The goal in view for which I strive alone. Love grants me powers that Nature might deny; And, whatsoe'er my doom, the world shall tell, Thy lover gave to immortality Her name he loved---so fatally---so well! A hundred arms were weak one block to move Of thousands, molded by the hand of Love Into fantastic shapes and forms of grace, Which crowd each nook of that majestic place. The piles give way, the rocky peaks divide, The stream comes gushing on---a foaming tide! A mighty work, for ages to remain, The token of his passion and his pain. As flows the milky flood from Allah's throne Rushes the torrent from the yielding stone; And sculptured there, amazed, stern Khosrow stands, And sees, with frowns, obeyed his harsh commands: While she, the fair beloved, with being rife, Awakes the glowing marble into life. Ah! hapless youth; ah! toil repaid by woe--- A king thy rival and the world thy foe! Will she wealth, splendor, pomp for thee resign--- And only genius, truth, and passion thine! Around the pair, lo! groups of courtiers wait, And slaves and pages crowd in solemn state; From columns imaged wreaths their garlands throw, And fretted roofs with stars appear to glow! Fresh leaves and blossoms seem around to spring, And feathered throngs their loves are murmuring; The hands of Peris might have wrought those stems, Where dewdrops hang their fragile diadems; And strings of pearl and sharp-cut diamonds shine, New from the wave, or recent from the mine. -

Proposing a Function for Char-Ghapi, Qasr-E-Shirin, Iran: Historical and Archaeological Evaluation

Original Article | Iran Heritage. 2019; 1(1): 66-81 Iran Heritage - ISSN 2676-5217 Proposing a Function for Char-Ghapi, Qasr-e-Shirin, Iran: Historical and Archaeological Evaluation Ali Hozhabri1,2* 1. MA in Archaeology; University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran 2. Iranian Center for the Museum Leadership, Cultural and Historical Properties Expert, Iranian Cultural Heritage, Handicraft and Tourism Organization, Tehran, Iran Article Info ABSTRACT Qasr-e Shirin owes its prominence primarily to the Sassanian period and the attention Use your device to scan the region received from Khosrow Parviz. Khosrow took the first steps to make Qasr-e- and read the article online Shirin habitable by constructing a complex consisting of a palace, a fortress, a religious building, a defensive wall and a water conveyance system. Later, Qasr-e-Shirin is mentioned in several texts and travel itineraries. The Char-Ghapi complex is generally attributed to the Sassanian king Khosrow II (590-628 A.D.), who allegedly constructed it for her Christian wife Shirin, thus the name Qasr-e-Shirin. Some historical sources make allusions to the buildings in Qasr-e-Shirin (Khosrow’s Mansion, Char-Ghapi). Char-Ghapi of Qasr-e-Shirin has a square ground plan with domed roof, known as chahar-taghi, which has attracted attention from many scholars, who have described it as a structure from the late Sassanian period. The majority of scholars have characterized its chahar-taq or square dome as a fire temple, while some have claimed that it formed part of a palace complex; a few writers have also expressed doubts as to its chronology, suggesting a date in the early Islamic period for it. -

PERSIAN MUSIC Sounding the City Still Singing A

Volume 12 - Number 2 February – March 2016 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: PPERSIANERSIAN MUSICMUSIC ● SSoundingounding thethe citycity ● SStilltill singingsinging ● A ddiscursiveiscursive studystudy ofof musicmusic inin IranIran duringduring thethe 1960s1960s ● SShapinghaping thethe PersianPersian repertoirerepertoire ● TThehe iintroductionntroduction ofof pianopiano practicepractice inin IranIran ● MMusic,usic, IIslamslam aandnd PPersianersian SuSufi ssmm ● MMusicusic oonn thethe mmoveove iinn thethe MMiddleiddle EastEast ● SSwayingwaying toto PersianPersian andand MiddleMiddle EasternEastern tunestunes inin LondonLondon ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews andand eventsevents inin LondonLondon Volume 12 - Number 2 February – March 2016 £4 TTHISHIS ISSUEISSUE: PPERSIANERSIAN MMUSICUSIC ● SSoundingounding tthehe ccityity ● SStilltill ssinginginging ● A ddiscursiveiscursive studystudy ooff mmusicusic iinn IIranran duringduring tthehe 11960s960s ● SShapinghaping tthehe PPersianersian rrepertoireepertoire ● TThehe iintroductionntroduction ooff ppianoiano ppracticeractice iinn IIranran ● MMusic,usic, IIslamslam aandnd PPersianersian SSuufi ssmm ● MMusicusic oonn tthehe mmoveove iinn tthehe MMiddleiddle EastEast ● SSwayingwaying ttoo PPersianersian andand MMiddleiddle EasternEastern ttunesunes iinn LondonLondon ● PPLUSLUS RReviewseviews aandnd eeventsvents inin LLondonondon Aida Foroutan, 'Protest', 2002. No. 14 of a series of 28 paintings called Women's Life, About the London Middle East Institute (LMEI) 2001-2015. Oil on canvas. 80 x 80 cm. Image courtesy of -

Aladdin Program.Pdf

Join us for our next production! Louisiana Tech University Theatre Presents e Wo nd th nder a fu in l L dd a a l m p A The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee April 30 — May 3, 2014 Winner of the 2005 Tony Award for Best Book of a Musical, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling 25th Anniversary Signature Event Bee follows six students of Putnam Valley Middle School as they compete in the annual spelling bee. However, this is not the average contest as audience members will be selected to participate in the bee. With the competition on, it is a fight to the finish as only one student can be v-i-c-t-o-r-i-o-u-s! Written by Michele L. Vacca @LATechTheatre Directed by Paul B. Crook January 31 - February 2, 2014 facebook.com/latechtheatre Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp is produced by special arrangement with CLASSICS ON STAGE! of Chicago For more information on our season and events, visit us at latechuniversitytheatre.com! Michele L. Vacca’s Become a Season Ticket Holder d the Wonde an rful dinThomas Comb* Hannah Miglicco L ad Trey Clark* Alma Moegle a l Tierra Jones Meihan Guo m p A Rashae Boyd Emmie Lancon Maddison Gilcrease Hannah Johnson Ashley Elizabeth Davis Orlando Librado Shelly Courtney VanEaton Carolyn Adele Smith* Jamie Lynn Robinson* Adam Garcia Set Design~Lighting Design Adam Spencer* Steven Vick* The Benefits: Costume Design Hair and Makeup Guaranteed Seats: The best seats are E-Minders: Season ticket holders will Kathryn Dumas Sarah Nguyen available for the entire season. -

The Enduring Legacy of the Mongol Catastrophe on the Political, Social

Abbas Edalat Trauma Hypothesis: The enduring legacy of the Mongol Catastrophe on the Political, Social and Scientific History of Iran1 Abstract We study the traumatic impact of the Mongol invasions, Ilkhanid rule and Timur’s conquests on Iran on the basis of our modern psychological understanding of trauma, and examine the long- term consequences and reenactments of this historic catastrophe on the political, social and scientific history of this country in later periods. By identifying new patterns of political and social violence in post-Mongol Iranian history, we provide evidence to support the Trauma Hypothesis and demonstrate how a transgenerational transfer of the Mongol trauma has taken place across both political and social spheres insofar as residues of certain traits of post-traumatic stress disorder have survived in large sections of the population. Finally, we postulate how these residual traits are preventing co-operation at a local and national level. Introduction This article provides the introductory synopsis to a study which seeks to analyze the psychological and emotional impact of the Mongol invasions, the Ilkhanid rule and the Timurid conquests on the political, social and scientific history of Iran. Its findings have been based on new advances in psychology and anthropology and have resulted in what we have termed “Trauma Hypothesis”. According to this hypothesis, during a period spanning approximately 200 years, Iran and, indeed, other Islamic societies in the Middle East and central Asia, suffered the kind of profound and sustained psychological trauma which has had lasting and ruinous consequences and traumatic reenactments, i.e., the tendency to re-experience the trauma, on the political, social, behavioral, ideological and cultural aspects of these societies and which, from a historical perspective, can be regarded as the root cause of the demise of the Golden Iranian- Islamic civilization. -

(Re)Framing the Storyteller's Story in John Adams's Scheherazade.2

(Re)Framing the Storyteller’s Story in John Adams’s Scheherazade.2 A thesis submitted to The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in Music History in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music March 2019 by Rebecca A. Schreiber B.M., Murray State University, May 2017 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract As a modern foil to Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade (1888), John Adams’s Scheherazade.2 (2014) offers an opportunity to evaluate program music’s potential to function as contemporary social commentary through narrativity and representation. I demonstrate how Adams’s dramatic symphony serves as an effective vehicle of critique of twenty-first-century dynamics surrounding gender and ethnic identity. Both Rimsky-Korsakov and Adams drew inspiration from One Thousand and One Nights, whose narrator Scheherazade overcomes the Sultan’s brutality through her storytelling. Adams expressly offers a new interpretation of Scheherazade by evoking modern images of physical, verbal, and emotional abuse faced by women around the world. I analyze Adams’s construction of the voice of an empowered woman by parsing his program and his collaboration with performer Leila Josefowicz, for whom Adams composed the violin’s narrative role. By examining intertextual relationships of musical narrative devices and signifiers between the portrayals of Rimsky-Korsakov and Adams, I argue that the narrative construction and treatment of thematic characters in Scheherazade.2 adhere to program music conventions while simultaneously re-positioning Scheherazade as a social commentator confronting contemporary oppression.