A Treasury from Tabriz: a Fourteenth-Century Manuscript Containing 209 Works in Persian and Arabic*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubai (Quatrain) As a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 4, Apr – 2018 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 30/04/2018 Rubai (Quatrain) as a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature Ms. Mina Qarizada Lecturer in Samangan Higher Education, Samangan, Afghanistan Master of Arts in English, Department of English Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Studying literature, including poetry and prose writing, in Afghanistan is very significant. Poetry provides some remarkable historical, cultural, and geographical facts and its literary legacy of a particular country. Understanding the poetic forms is important in order to understand the themes and the styles of the poetry of the poets. All the Persian poets in some points of the time composed in the Rubai form which is very common till now among the past and present generation across Afghanistan. This paper is an overview of Rubai as a classical form of Poetry in Persian Literature. Rubai has its significant role in the society with different stylistic and themes related to the cultural, social, political, and gender based issues. The key features of Rubai are to be eloquent, spontaneous and ingenious. In a Rubai the first part is the introduction which is the first three lines that is the sublime for the fourth line of the poem. It represents the idea if sublet, pithy and clever. It also represents the poets’ literary works, poetic themes, styles, and visions. Key Words: Rubai, Classic, Poetry, Persian, Literature, Quatrain, 1. INTRODUCTION: Widespread geography of Persian speakers during the past centuries in the history of Afghanistan like many other countries, it can be seen and felt that only great men were trained in the fields of art and literature. -

Bright Typing Company

Tape Transcription Islam Lecture No. 1 Rule of Law Professor Ahmad Dallal ERIK JENSEN: Now, turning to the introduction of our distinguished lecturer this afternoon, Ahmad Dallal is a professor of Middle Eastern History at Stanford. He is no stranger to those of you within the Stanford community. Since September 11, 2002 [sic], Stanford has called on Professor Dallal countless times to provide a much deeper perspective on contemporary issues. Before joining Stanford's History Department in 2000, Professor Dallal taught at Yale and Smith College. Professor Dallal earned his Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University and his academic training and research covers the history of disciplines of learning in Muslim societies and early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. He is currently finishing a book-length comparative study of eighteenth century Islamic reforms. On a personal note, Ahmad has been terrifically helpful and supportive, as my teaching assistant extraordinaire, Shirin Sinnar, a third-year law student, and I developed this lecture series and seminar over these many months. Professor Dallal is a remarkable Stanford asset. Frederick the Great once said that one must understand the whole before one peers into its parts. Helping us to understand the whole is Professor Dallal's charge this afternoon. Professor Dallal will provide us with an overview of the historical development of Islamic law and may provide us with surprising insights into the relationship of Islam and Islamic law to the state and political authority. He assures us this lecture has not been delivered before. So without further ado, it is my absolute pleasure to turn over the podium to Professor Dallal. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

“The Spinning of the Mill Lightens My Soul”1

PERSICA XVII, 2001 “THE SPINNING OF THE MILL LIGHTENS MY SOUL”1 Asghar Seyed-Gohrab Leiden University Introduction Within a more than four centuries old relationship between Dutch and Persian culture, there are a wide range of subjects luring the researcher to launch an investigation.2 One may, for instance, choose to examine the Persian names of flowers in Dutch, or to linger on Rembrandt’s interest in the Persian miniature painting, or to study the 17th century translation of Sa‘di’s (d. 1292) Bustan in Dutch and so on and so forth.3 As a native Per- sian living in the country of tulips, clogs and mills, I have chosen to study the mill in Persian literature. In recent years I have been more and more fascinated by the mills in the foggy, flat and green Dutch landscape, while being constantly reminded of the wide- spread literary metaphors, popular beliefs, riddles, proverbs and folksongs based on this ancient invention of mankind in Persian literature. It should be, however, stated at the outset that although I deal briefly with the relationship between ancient Persian windmills and their Western counterparts, this essay does not pretend to peruse the link between these windmills; the study is an attempt to demonstrate how the mill, whether a windmill, watermill or handmill, is presented in Persian literary sources as well as in popular ex- pressions. Moreover, a study of the mill at literary level is conductive; especially since in molinological literature, Persian literary sources are usually neglected. It is generally believed that the Persians played a major role in the invention, the development and the spread of the mill. -

Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

REFRAMING BORDERS: A STUDY OF THE VEIL, WRITING, AND REPRESENTATION OF THE FEMALE BODY IN THE PHOTO-BASED ARTWORK OF MONA HATOUM, SHIRIN NESHAT, AND LALLA ESSAYDI by MARYAM A M A ALWAZZAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Maryam A M A Alwazzan Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of the femaLe body In the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi This thesIs has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Master of Art HIstory degree in the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture by: Kate Mondloch ChaIr Derek Burdette Member MIchaeL Allan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018. II © 2018 Maryam A M A ALwazzan This work is lIcensed under a CreatIve Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. III THESIS ABSTRACT Maryam A M A ALwazzan Master of Arts Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture December 2018 Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of The Female Body In The Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi For a long tIme, most women beLIeved they had to choose between theIr MusLIm or Arab identIty and theIr beLIef in socIaL equaLIty of sexes. -

ʿaishī's ʿishrat-Nāma a Dah-Nāma with Unexpected Messengers

e-ISSN 2385-3042 ISSN 1125-3789 Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale Vol. 56 – Giugno 2020 ʿAishī’s ʿIshrat-nāma A Dah-nāma with Unexpected Messengers Anna Livia Beelaert Leiden, The Netherlands Abstract In the first part of this article I presented an edition with a short introduction of ʿAishī Shīrāzī’s ʿIshrat-nāma, a poem belonging to the dah-nāma genre. In this second part I discuss the messengers who convey the messages between the two lovers. At the request of his patron, ʿInāyat, an amir of the Aq-Quyūnlū Khalīl b. Uzun Ḥasan, instead of the usual messenger, the wind, ʿAishī chose for ten musical instruments. I argue that the choice of these instruments, and the way they are decribed, are not accidental but subtly convey the evolution of the protagonists’ feelings. Keywords ʿAishī Shīrāzī. ʿIshrat-nāma. Dah-nāma. Mathnawī. Musical Instruments. Messenger Motif. Summary 1 Introduction. – 2 The Origin of the Dah-nāma Genre: Wīs u Rāmīn and Khusrau u Shīrīn. – 3 The Other Sources of Inspiration of the ʿIshrat-nāma. – 4 Structure of the Poem. – 5 The Instruments as Messengers. – 6 Conclusion. Peer review Submitted 2018-02-05 Edizioni Accepted 2018-04-17 Ca’Foscari Published 2020-06-30 Open access © 2020 | cb Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License Citation Beelaert, Anna Livia (2020). “ʿAishī’s ʿIshrat-nāma: A Dah-nāma with Unexpected Messengers”. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie orientale, 56, 197-218. DOI 10.30687/AnnOr/2385-3042/2020/56/008 197 Anna Livia Beelaert ʿAishī’s ʿIshrat-nāma: A Dah-nāma with Unexpected Messengers For Jan Schmidt 1 Introduction ʿAishī’s ʿIshrat-nāma (Book of Enjoyment [or Pleasure]) is a little- known poem, belonging to the genre dah-nāma, which, as it seems, has come down to us in a single manuscript at the Bibliothèque Na- tionale in Paris (Suppl. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

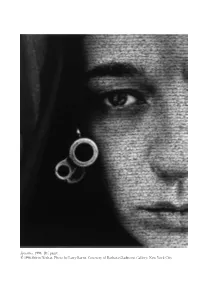

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 2 (2010) Jan W. Żelazny Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków The legend of Shirin in Syriac sources. A warning against caesaropapism? Why was Syriac Christianity not an imperial Church? Why did it not enter into a relationship with the authorities? This can be explained by pointing to the political situation of that community. I think that one of the reasons was bad experiences from the time of Chosroes II. The Story of Chosroes II The life of Chosroes II Parviz is a story of rise and fall. Although Chosroes II became later a symbol of the power of Persia and its ancient independence, he encountered numerous difficulties from the very moment he ascended the throne. Chosroes II took power in circumstances that today remain obscure – as it was frequently the case at the Persian court – and was raised to the throne by a coup. The rebel was inspired by an attempt of his father, Hormizd IV, to oust one of the generals, Bahram Cobin, which provoked a powerful reaction among the Persian aristocracy. The question concerning Chosroes II’s involvement in the conspiracy still remains unanswered; however, Chosroes II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father. Soon after, Hormizd IV died in prison in ambiguous circumstances. The Arabic historian, al-Tabari, claimed that Chosroes was oblivious of the rebellion. However, al-Tabari works were written several centuries later, at a time when the legend of the shah was already deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people. -

DISTINGUISHED WOMEN in HISTORY of AZERBAIJANI ATABAY, AQ QOYUNLU and SAFAVID STATES Conclusion

42, WINTER 2019 Nargiz F. AKHUNDOVA PhD in History DISTINGUISHED WOMEN IN HISTORY OF AZERBAIJANI ATABAY, AQ QOYUNLU AND SAFAVID STATES Conclusion. See the beginning in IRS-Heritage, № 41, 2019 www.irs-az.com 5 From the past his list of outstanding women’s names could be mon knowledge that the Azerbaijani Ildeniz rulers, in continued. However, the personality of Momine fact, were subsequently at the helm of state. It is note- TKhatun, the wife of Azerbaijani atabay (ruler) worthy that Z. M. Buniyadov made a substantial contri- Ildeniz and mother of prominent Ildenizid rulers Jahan bution to the studies regarding the nearly century-long Pahlavan (1175-1186) and Qizil Arslan, is particularly re- historical period of the Atabay state’s existence. The markable. The concept of women’s governing role in Orientalist conducted extensive research of the avail- the state system in the Atabay state should be generally able sources. The Arabic language sources he studied emphasized as well. included Ibn al-Asir’s (1160-1233) (“al-Kamil fi-t-ta rikh” This personality existed during an earlier era that was or ”Perfect on history”), Sibt al-Jawzi’s (1185-1256) “Mir by far no less tension-filled than that of the previously at az-zaman fi-tarikh al-ayan” (“The mirror of time in the mentioned Sara Khatun and Tajlu Begim, i.e. the epoch chronicle of celebrities”), Sadr ad-Din Ali al-Husayni’s of the Ildenizid state (1136-1225). This time period is of- “Zubdat at-tavarikh fi akhbar al-umara va-l-mulyuk as- ten referred to by historiographers as the Renaissance Seljuqiyya” (“The cream of the crop in the chronicles epoch, which saw the emergence of great poets, po- that contain data about Seljuq Emirs and rulers”), etc. -

The University of Chicago Poetry

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO POETRY AND PEDAGOGY: THE HOMILETIC VERSE OF FARID AL-DIN ʿAṬṬÂR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY AUSTIN O’MALLEY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2017 © Austin O’Malley 2017 All Rights Reserved For Nazafarin and Almas Table of Contents List of Tables .......................................................................................................................................vi Note on Transliteration ...................................................................................................................vii Acknowledgments...........................................................................................................................viii Introduction..........................................................................................................................................1 I. ʿAṭṭâr, Preacher and Poet.................................................................................................................10 ʿAṭṭâr’s Oeuvre and the Problem of Spurious Atributions..............................................12 Te Shiʿi ʿAṭṭâr.......................................................................................................................15 Te Case of the Wandering Titles.......................................................................................22 Biography and Social Milieu....................................................................................................30 -

The False Caliph ROBERT G

The False Caliph ROBERT G. HAMPSON 1 heat or no heat, the windows have to be shut. nights like this, the wind winds down through the mountain passes and itches the skin on the backs of necks: anything can happen. 2 voices on the radio drop soundless as spring rain into the murmur of general conversation. his gloved hands tap lightly on the table-top as he whistles tunelessly to himself. his partner picks through a pack of cards, plucks out the jokers and lays down a mat face down in front of him. 285 286 The 'Arabian Nights' in English Literature the third hones his knife on the sole of his boot: tests its edge with his thumb. 3 Harry can't sleep. Mezz and the boys, night after night, have sought means to amuse him to cheat the time till dawn brings the tiredness that finally takes him. but tonight everything has failed. neither card-tricks nor knife-tricks - not even the prospect of nocturnal adventures down in the old town has lifted his gloom. they're completely at a loss. then the stranger enters: the same build the same face the same dress right down to the identical black leather gloves on the hands The False Caliph 287 which now tap contemptuously on the table while he whistles tunelessly as if to himself. Appendix W. F. Kirby's 'Comyarative Table of the Tales in the Principal Editions o the Thousand and One Nights' from fhe Burton Edition (1885). [List of editions] 1. Galland, 1704-7 2. Caussin de Perceval, 1806 3.