Proposing a Function for Char-Ghapi, Qasr-E-Shirin, Iran: Historical and Archaeological Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sacred Celestial Motif: an Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Mazloumi & Nasrollahzadeh, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 2, pp. 682 - 699 Date of Publication: 16th September, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.32.682699 This paper can be cited as: Mazloumi, Y., & Nasrollahzadeh, C. (2017). A Sacred Celestial Motif: An Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(2), 682-699. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. A SACRED CELESTIAL MOTIF: AN INTRODUCTION TO WINGED ANGELS ICONOGRAPHY IN IRAN Yasaman Nabati Mazloumi M.A in Iranian Studies, Shahid Beheshti University, Daneshjoo Blvd, Velenjak, Street, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Cyrus Nasrollahzadeh Associate Professor, Department of Ancient Iranian Culture and Languages, Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 64th Street, Kurdestan Expressway, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract Through history many motifs have been created and over the centuries, some of them turned into very well-known symbols. One of these motifs is winged angel. This sacred and divine creature which appears in human-shaped, serves intermediaries between the God and people, and during history, indicates legitimating and bestows God-given glory. This article aims to present the results of exploring the historical background of the winged angels in Iran, in order to understand its precise concept; where it comes from and what it resembles. -

Bright Typing Company

Tape Transcription Islam Lecture No. 1 Rule of Law Professor Ahmad Dallal ERIK JENSEN: Now, turning to the introduction of our distinguished lecturer this afternoon, Ahmad Dallal is a professor of Middle Eastern History at Stanford. He is no stranger to those of you within the Stanford community. Since September 11, 2002 [sic], Stanford has called on Professor Dallal countless times to provide a much deeper perspective on contemporary issues. Before joining Stanford's History Department in 2000, Professor Dallal taught at Yale and Smith College. Professor Dallal earned his Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University and his academic training and research covers the history of disciplines of learning in Muslim societies and early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. He is currently finishing a book-length comparative study of eighteenth century Islamic reforms. On a personal note, Ahmad has been terrifically helpful and supportive, as my teaching assistant extraordinaire, Shirin Sinnar, a third-year law student, and I developed this lecture series and seminar over these many months. Professor Dallal is a remarkable Stanford asset. Frederick the Great once said that one must understand the whole before one peers into its parts. Helping us to understand the whole is Professor Dallal's charge this afternoon. Professor Dallal will provide us with an overview of the historical development of Islamic law and may provide us with surprising insights into the relationship of Islam and Islamic law to the state and political authority. He assures us this lecture has not been delivered before. So without further ado, it is my absolute pleasure to turn over the podium to Professor Dallal. -

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism

Nestorianism 1 Nestorianism For the church sometimes known as the Nestorian Church, see Church of the East. "Nestorian" redirects here. For other uses, see Nestorian (disambiguation). Nestorianism is a Christological doctrine advanced by Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople from 428–431. The doctrine, which was informed by Nestorius' studies under Theodore of Mopsuestia at the School of Antioch, emphasizes the disunion between the human and divine natures of Jesus. Nestorius' teachings brought him into conflict with some other prominent church leaders, most notably Cyril of Alexandria, who criticized especially his rejection of the title Theotokos ("Bringer forth of God") for the Virgin Mary. Nestorius and his teachings were eventually condemned as heretical at the First Council of Ephesus in 431 and the Council of Chalcedon in 451, leading to the Nestorian Schism in which churches supporting Nestorius broke with the rest of the Christian Church. Afterward many of Nestorius' supporters relocated to Sassanid Persia, where they affiliated with the local Christian community, known as the Church of the East. Over the next decades the Church of the East became increasingly Nestorian in doctrine, leading it to be known alternately as the Nestorian Church. Nestorianism is a form of dyophysitism, and can be seen as the antithesis to monophysitism, which emerged in reaction to Nestorianism. Where Nestorianism holds that Christ had two loosely-united natures, divine and human, monophysitism holds that he had but a single nature, his human nature being absorbed into his divinity. A brief definition of Nestorian Christology can be given as: "Jesus Christ, who is not identical with the Son but personally united with the Son, who lives in him, is one hypostasis and one nature: human."[1] Both Nestorianism and monophysitism were condemned as heretical at the Council of Chalcedon. -

“The Qur'an and the Modern Self: a Heterotopia,”

“The Qur’an and the Modern Self: A Heterotopia,” Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 85, No. 3, Fall 2018, pp. 557-572. No book has been so vilified in the Christian West, while at the same time remaining so almost completely unread, as the Qur’an. Those who did at least delve into it put it to numerous and contradictory purposes. Churchmen such as Martin Luther cited it as the ultimate heresy. Enlightenment intellectuals such as Thomas Jefferson valued it for its post-pagan monotheism. In the early decades of the twenty-first century it has been libeled as a font of terrorism. Yet it is the scripture of a quarter of humankind. Prominent writers have often engaged with it as a staccato “heterotopia,” one continually constructed and forgotten, since for all its importance, it has never been part of the literary canon. We have come to the book by diverse and winding pathways. Author Al Young, whom Arnold Schwarzenegger as governor appointed California’s poet laureate, spoke of the profound influence on his craft of the music of jazz legend Yusef Lateef, whose performances he used to attend while growing up in Detroit. He wrote, “That he was Muslim intrigued us. Eventually, to understand a little about where Yusef was coming from, I read British Muslim Marmaduke Pickthall’s translation of the Qur’an: The Glorious Koran. And I was moved” (Young 2013). Between the utopia and the dystopia Michel Foucault positioned the heterotopia, a place in- between, juxtaposed to but not part of the world. He mentioned as examples “the garden, brothel, rest home, festival, magic carpet, Muslim baths” and even “Persian gardens” and “the cemetery” (Johnson 2013). -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

The Syrian Orthodox Church and Its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, I-Iii (Rome, 2001)

Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 5:1, 63-112 © 2002 by Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute SOME BASIC ANNOTATION TO THE HIDDEN PEARL: THE SYRIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH AND ITS ANCIENT ARAMAIC HERITAGE, I-III (ROME, 2001) SEBASTIAN P. BROCK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD [1] The three volumes, entitled The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage, published by TransWorld Film Italia in 2001, were commisioned to accompany three documentaries. The connecting thread throughout the three millennia that are covered is the Aramaic language with its various dialects, though the emphasis is always on the users of the language, rather than the language itself. Since the documentaries were commissioned by the Syrian Orthodox community, part of the third volume focuses on developments specific to them, but elsewhere the aim has been to be inclusive, not only of the other Syriac Churches, but also of other communities using Aramaic, both in the past and, to some extent at least, in the present. [2] The volumes were written with a non-specialist audience in mind and so there are no footnotes; since, however, some of the inscriptions and manuscripts etc. which are referred to may not always be readily identifiable to scholars, the opportunity has been taken to benefit from the hospitality of Hugoye in order to provide some basic annotation, in addition to the section “For Further Reading” at the end of each volume. Needless to say, in providing this annotation no attempt has been made to provide a proper 63 64 Sebastian P. Brock bibliography to all the different topics covered; rather, the aim is simply to provide specific references for some of the more obscure items. -

Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

REFRAMING BORDERS: A STUDY OF THE VEIL, WRITING, AND REPRESENTATION OF THE FEMALE BODY IN THE PHOTO-BASED ARTWORK OF MONA HATOUM, SHIRIN NESHAT, AND LALLA ESSAYDI by MARYAM A M A ALWAZZAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Maryam A M A Alwazzan Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of the femaLe body In the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi This thesIs has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Master of Art HIstory degree in the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture by: Kate Mondloch ChaIr Derek Burdette Member MIchaeL Allan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018. II © 2018 Maryam A M A ALwazzan This work is lIcensed under a CreatIve Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. III THESIS ABSTRACT Maryam A M A ALwazzan Master of Arts Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture December 2018 Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of The Female Body In The Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi For a long tIme, most women beLIeved they had to choose between theIr MusLIm or Arab identIty and theIr beLIef in socIaL equaLIty of sexes. -

Download Article (PDF)

RECENT PUBLICATIONS ON SYRIAC TOPICS: 2018* SEBASTIAN P. BROCK, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD GRIGORY KESSEL, AUSTRIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER SERGEY MINOV, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD Books Acharya, F., Psalmic Odes from Apostolic Times: An Indian Monk’s Meditation (Bengaluru: ATC Publishers, 2018). Adelman, S., After Saturday Comes Sunday (Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press, 2018). Alobaidi, T., and Dweik, B., Language Contact and the Syriac Language of the Assyrians in Iraq (Saarbrücken, Germany: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2018). Andrade, N.J., The Journey of Christianity to India in Late Antiquity: Networks and the Movement of Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). Aravackal, R., The Mystery of the Triple Gradated Church: A Theological Analysis of the Kṯāḇā d-Massqāṯā (Book of Steps) with Particular Reference to the Writing of Aphrahat and John the Solitary (Oriental Institute of Religious Studies India Publications 437; Kottayam, India: Oriental Institute of Religious Studies, 2018). Aydin, G. (ed.), Syriac Hymnal According to the Rite of the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch (Teaneck, New Jersey: Beth Antioch Press / Syriac Music Institute, 2018). Bacall, J., Chaldean Iraqi American Association of Michigan (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2018). * The list of publications is based on the online Comprehensive Bibliography on Syriac Christianity, supported by the Center for the Study of Christianity at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (http://www.csc.org.il/db/db.aspx?db=SB). Suggested additions and corrections can be sent to: [email protected] 235 236 Bibliographies Barry, S.C., Syriac Medicine and Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq’s Arabic Translation of the Hippocratic Aphorisms (Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement 39; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

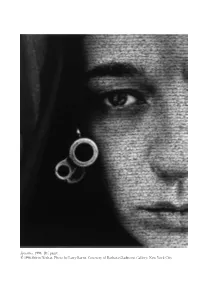

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 2 (2010) Jan W. Żelazny Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków The legend of Shirin in Syriac sources. A warning against caesaropapism? Why was Syriac Christianity not an imperial Church? Why did it not enter into a relationship with the authorities? This can be explained by pointing to the political situation of that community. I think that one of the reasons was bad experiences from the time of Chosroes II. The Story of Chosroes II The life of Chosroes II Parviz is a story of rise and fall. Although Chosroes II became later a symbol of the power of Persia and its ancient independence, he encountered numerous difficulties from the very moment he ascended the throne. Chosroes II took power in circumstances that today remain obscure – as it was frequently the case at the Persian court – and was raised to the throne by a coup. The rebel was inspired by an attempt of his father, Hormizd IV, to oust one of the generals, Bahram Cobin, which provoked a powerful reaction among the Persian aristocracy. The question concerning Chosroes II’s involvement in the conspiracy still remains unanswered; however, Chosroes II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father. Soon after, Hormizd IV died in prison in ambiguous circumstances. The Arabic historian, al-Tabari, claimed that Chosroes was oblivious of the rebellion. However, al-Tabari works were written several centuries later, at a time when the legend of the shah was already deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people.