Or Politics Matters the Book of Esther

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs: Videos: Purim Song – The Maccabeats Audio Reading: Book of Esther Feast of Purim Purim is an annual celebration of the defeat of an Iranian mad man’s plan to exterminate the Jewish people. Purim is celebrated annually during the month of Adar (the second month of Adar) on the 14th day. In years where there are two months of Adar, Purim is celebrated in the second month because it always needs to fall 30 days before Passover. It is called Purim because the word means “lots” – referencing when Haman threw lots to decide which day he would slay the Jews. The fourteenth was chosen for this celebration because it is the day that the Jews battled for their lives and won. The fifteenth is celebrated as Purim also because the book of Esther says that in Shushan (a walled city), deliverance from the scheduled massacre was not completed until the next day. So the fifteenth is referred to as Shushan Purim. Traditions for the Feast of Purim: It is customary to read the book of Esther – called the Megillah Esther – or the scroll of Esther. It means the revelation of that which is hidden While reading it is tradition to boo, hiss, stamp feet and rattle noise makers whenever Haman’s name is mentioned for the purpose of “blotting out the name of Haman”. When the names of Mordechai or Esther are spoken, hoots and hollers, cheering, applause, etc., are given as they are the heroes of the story. -

A Sacred Celestial Motif: an Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran

PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences ISSN 2454-5899 Mazloumi & Nasrollahzadeh, 2017 Volume 3 Issue 2, pp. 682 - 699 Date of Publication: 16th September, 2017 DOI-https://dx.doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.32.682699 This paper can be cited as: Mazloumi, Y., & Nasrollahzadeh, C. (2017). A Sacred Celestial Motif: An Introduction to Winged Angels Iconography in Iran. PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(2), 682-699. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. A SACRED CELESTIAL MOTIF: AN INTRODUCTION TO WINGED ANGELS ICONOGRAPHY IN IRAN Yasaman Nabati Mazloumi M.A in Iranian Studies, Shahid Beheshti University, Daneshjoo Blvd, Velenjak, Street, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Cyrus Nasrollahzadeh Associate Professor, Department of Ancient Iranian Culture and Languages, Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, 64th Street, Kurdestan Expressway, Tehran, Iran [email protected] Abstract Through history many motifs have been created and over the centuries, some of them turned into very well-known symbols. One of these motifs is winged angel. This sacred and divine creature which appears in human-shaped, serves intermediaries between the God and people, and during history, indicates legitimating and bestows God-given glory. This article aims to present the results of exploring the historical background of the winged angels in Iran, in order to understand its precise concept; where it comes from and what it resembles. -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

Esther Through the Centuries (Blackwell Bible Commentaries)

Esther Through the Centuries Jo Carruthers Esther Through the Centuries Blackwell Bible Commentaries Series Editors: John Sawyer, Christopher Rowland, Judith Kovacs, David M. Gunn John Th rough the Centuries Ecclesiastes Th rough the Centuries Mark Edwards Eric S. Christianson Revelation Th rough the Centuries Esther Th rough the Centuries Judith Kovacs & Christopher Rowland Jo Carruthers Judges Th rough the Centuries Psalms Th rough the Centuries: David M. Gunn Volume One Exodus Th rough the Centuries Susan Gillingham Scott M. Langston Galatians Th rough the Centuries John Riches Forthcoming: Leviticus Th rough the Centuries Th e Minor Prophets Th rough the Mark Elliott Centuries 1 & 2 Samuel Th rough the Centuries Jin Han & Richard Coggins David M. Gunn Mark Th rough the Centuries 1 & 2 Kings Th rough the Centuries Christine Joynes Martin O’Kane Luke Th rough the Centuries Psalms Th rough the Centuries: Larry Kreitzer Volume Two Th e Acts of the Apostles Th rough the Susan Gillingham Centuries Song of Songs Th rough the Centuries Heidi J. Hornik & Mikael C. Parsons Francis Landy & Fiona Black Romans Th rough the Centuries Isaiah Th rough the Centuries Paul Fiddes John F. A. Sawyer 1 Corinthians Th rough the Centuries Jeremiah Th rough the Centuries Jorunn Okland Mary Chilton Callaway 2 Corinthians Th rough the Centuries Lamentations Th rough the Centuries Paula Gooder Paul M. Joyce & Diane Lipton Hebrews Th rough the Centuries Ezekiel Th rough the Centuries John Lyons Andrew Mein James Th rough the Centuries Jonah Th rough the Centuries David Gowler Yvonne Sherwood Pastoral Epistles Th rough the Centuries Jay Twomey Esther Through the Centuries Jo Carruthers © by Jo Carruthers blackwell publishing Main Street, Malden, MA - , USA Garsington Road, Oxford OX DQ, UK Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria , Australia Th e right of Jo Carruthers to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act . -

![Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4834/prints-and-johan-wittert-van-der-aa-in-the-rijksmuseum-in-amsterdam-7-drawings-inv-254834.webp)

Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv

Esther before Ahasuerus ca. 1640–45 oil on panel Jan Adriaensz van Staveren 86.7 x 75.2 cm (Leiden 1613/14 – 1669 Leiden) signed in light paint along angel’s shield on armrest of king’s throne: “JOHANNES STAVEREN 1(6?)(??)” JvS-100 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Esther before Ahasuerus Page 2 of 9 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Esther before Ahasuerus” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/esther-before-ahasuerus/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Esther before Ahasuerus Page 3 of 9 During the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, the beautiful Jewish orphan Comparative Figures Esther, heroine of the Old Testament Book of Esther, won the heart of the austere Persian king Ahasuerus and became his wife (Esther 2:17). Esther had been raised by her cousin Mordecai, who made Esther swear that she would keep her Jewish identity a secret from her husband. However, when Ahasuerus appointed as his minister the anti-Semite Haman, who issued a decree to kill all Jews, Mordecai begged Esther to reveal her Jewish heritage to Ahasuerus and plead for the lives of her people. Esther agreed, saying to Mordecai: “I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. -

Esther Nelson, Stanford Calderwood General

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR THE MISSION OF BOSTON LYRIC OPERA IS TO BUILD CURIOSITY, ENTHUSIASM AND SUPPORT FOR OPERA BY CREATING MUSICALLY AND THEATRICALLY COMPELLING PRODUCTIONS, EVENTS, AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES FOR THE BOSTON COMMUNITY AND BEYOND. B | BOSTON LYRIC OPERA OVERVIEW: ANNUAL REPORT 2017 WELCOME Dear Patrons, Art is often inspired by the idea of a journey. Boston Lyric Opera’s 40TH Anniversary Season was a journey from Season opener to Season closer, with surprising and enlightening stories along the way, lessons learned, and strengths found. Together with you, we embraced the unexpected, and our organization was left stronger as a result. Our first year of producing works in multiple theaters was thrilling and eye-opening. REPORT Operas were staged in several of Boston’s best houses and uniformly received blockbuster reviews. We made an asset of being nimble, seizing upon the opportunity CONTENTS of our Anniversary Season to create and celebrate opera across our community. Best of all, our journey brought us closer than ever to our audiences. Welcome 1 It’s no coincidence that the 2016/17 Season opened with Calixto Bieito’s renowned 2016/17 Season: By the Numbers 2 staging of Carmen, in co-production with San Francisco Opera. The strong-willed gypsy Leadership & Staff 3 woman and the itinerant community she adopted was a perfect metaphor for our first production on the road. Bringing opera back to the Boston Opera House was an iconic 40TH Anniversary Kickoff 4 moment. Not only did Carmen become the Company’s biggest-selling show ever, it also Carmen 6 ignited a buzz around the community that drew a younger, more diverse audience. -

“The Qur'an and the Modern Self: a Heterotopia,”

“The Qur’an and the Modern Self: A Heterotopia,” Social Research: An International Quarterly, Volume 85, No. 3, Fall 2018, pp. 557-572. No book has been so vilified in the Christian West, while at the same time remaining so almost completely unread, as the Qur’an. Those who did at least delve into it put it to numerous and contradictory purposes. Churchmen such as Martin Luther cited it as the ultimate heresy. Enlightenment intellectuals such as Thomas Jefferson valued it for its post-pagan monotheism. In the early decades of the twenty-first century it has been libeled as a font of terrorism. Yet it is the scripture of a quarter of humankind. Prominent writers have often engaged with it as a staccato “heterotopia,” one continually constructed and forgotten, since for all its importance, it has never been part of the literary canon. We have come to the book by diverse and winding pathways. Author Al Young, whom Arnold Schwarzenegger as governor appointed California’s poet laureate, spoke of the profound influence on his craft of the music of jazz legend Yusef Lateef, whose performances he used to attend while growing up in Detroit. He wrote, “That he was Muslim intrigued us. Eventually, to understand a little about where Yusef was coming from, I read British Muslim Marmaduke Pickthall’s translation of the Qur’an: The Glorious Koran. And I was moved” (Young 2013). Between the utopia and the dystopia Michel Foucault positioned the heterotopia, a place in- between, juxtaposed to but not part of the world. He mentioned as examples “the garden, brothel, rest home, festival, magic carpet, Muslim baths” and even “Persian gardens” and “the cemetery” (Johnson 2013). -

170305 Ezekiel Introduction Sermon Notes

Spring 2017 – Ezekiel – Introduction and Overview (6 March 2017, Paul Langham) INTRODUCTION Where is God when you need him? Is God really everything our leaders say he is? Is God really everything The Book says he is? How can I believe in and worship the ‘One, true God’ when the gods of the world in which I find myself seem so much more potent and powerful? How can I trust that God really is in control when the circumstances of my life seem to shout the very opposite? If any of those questions resonates with you, the book of Ezekiel is a must read. Questions very like those were on the lips of God’s people in Exile, strangers in a strange land, far from home, the City and its Temple whiCh housed the worship of the God they had been told was Lord of heaven and earth, lay in ruins … EZEKIEL IN THE BIBLICAL CONTEXT (see appendix 1 for more detail) Old Testament Era Designation HistoriCal Books CharaCter/ Events 1. Pre-history CREATION Genesis 1 – 11 Adam & Eve Noah & Flood Tower of Babel 2. 1950 – 1280 BC PATRIARCHS Genesis 12 – 50 Abraham IsaaC JaCob Joseph 3. 1280 – 1240 EXODUS Exodus Moses LevitiCus Joshua Numbers Deuteronomy 4. 1240 – 1200 CONQUEST Joshua Crossing Jordan Walls of JeriCho Settlement of land 5. 1200 – 1020 JUDGES Judges Deborah Ruth Gideon Samson Ruth 6. 1020 – 587 KINGDOM * 1 & 2 Samuel Samuel 1 & 2 Kings Saul 1 & 2 ChroniCles David [Goliath] Solomon * 928 BC On the death of Solomon, the KINGDOM divided into • Northern Kingdom (Israel), 20 kings from 928 to 722 BC (Samaria falls to Assyrians) 1 • Southern Kingdom (Judah), 21 kings from 928 to 587/6 BC (Jerusalem falls to Babylonians) All the ‘Wisdom’ literature (Psalms, Proverbs, Job, ECClesiastes, Song of Solomon) written during this period. -

2015 in the Penal Colony Program

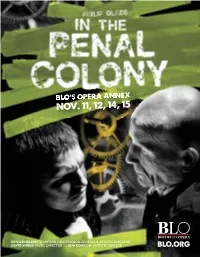

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR Rodolfo (Jesus Garcia) and Mimi (Kelly Kaduce) in Boston Lyric Opera’s 2015 production of La Bohème. This holiday season, share your love of opera with the ones you love. BLO off ers packages and gift certifi cates CHARLES ERICKSON T. to make your holiday shopping simple! T. CHARLES ERICKSON T. WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH IN OUR OPERA ANNEX SERIES, which is increasingly attracting national and international attention. Installing opera in non-conventional spaces has sparked a curiosity in the art. The challenges of these spaces are many and due to opera’s inherent demands: natural acoustics (since we do not amplify), adequate performance and production space, audience comfort and social space, location accessibility, parking, safety, and especially important in New England, adequate heat. Our In the Penal Colony comes amid questions and debate on the performance spaces and theatrical environment in Boston. For us, the questions include … why is Boston the only one of the top ten U.S. cities without a home suitable for opera? What are sustainable models to support new performance venues and/or preserve historic theaters? As you may have heard, BLO decided not to renew its agreement with the JesusJJesus GarciaGGarcia as RRoRodolfodldolffo Shubert Theatre after this Season. The reasons are many and complex, but suffi ce in La Bohème it to say that we made an important business and artistic decision. BLO is dedicated to spending signifi cantly more of our budget on direct artistic and production expenses and providing our patrons with a new level of service and comfort. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry.