The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Empire of Iran by Michael R.J

The Last Empire of Iran By Michael R.J. Bonner In 330 BCE, Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian imperial capital at Persepolis. This was the end of the world’s first great international empire. The ancient imperial traditions of the Near East had culminated in the rule of the Persian king Cyrus the Great. He and his successors united nearly all the civilised people of western Eurasia into a single state stretching, at its height, from Egypt to India. This state perished in the flames of Persepolis, but the dream of world empire never died. The Macedonian conquerors were gradually overthrown and replaced by a loose assemblage of Iranian kingdoms. The so-called Parthian Empire was a decentralised and disorderly state, but it bound together much of the sedentary Near East for about 500 years. When this empire fell in its turn, Iran got a new leader and new empire with a vengeance. The third and last pre-Islamic Iranian empire was ruled by the Sasanian dynasty from the 220s to 651 CE. Map of the Sasanian Empire. Silver coin of Ardashir I, struck at the Hamadan mint. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Silver_coin_of_Ardashir_I,_struck_at_the_Hamadan _mint.jpg) The Last Empire of Iran. This period was arguably the heyday of ancient Iran – a time when Iranian military power nearly conquered the eastern Roman Empire, and when Persian culture reached its apogee before the coming of Islam. The founder of the Sasamian dynasty was Ardashir I who claimed descent from a mysterious ancestor called Sasan. Ardashir was the governor of Fars, a province in southern Iran, in the twilight days of the Parthian Empire. -

Bright Typing Company

Tape Transcription Islam Lecture No. 1 Rule of Law Professor Ahmad Dallal ERIK JENSEN: Now, turning to the introduction of our distinguished lecturer this afternoon, Ahmad Dallal is a professor of Middle Eastern History at Stanford. He is no stranger to those of you within the Stanford community. Since September 11, 2002 [sic], Stanford has called on Professor Dallal countless times to provide a much deeper perspective on contemporary issues. Before joining Stanford's History Department in 2000, Professor Dallal taught at Yale and Smith College. Professor Dallal earned his Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University and his academic training and research covers the history of disciplines of learning in Muslim societies and early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. He is currently finishing a book-length comparative study of eighteenth century Islamic reforms. On a personal note, Ahmad has been terrifically helpful and supportive, as my teaching assistant extraordinaire, Shirin Sinnar, a third-year law student, and I developed this lecture series and seminar over these many months. Professor Dallal is a remarkable Stanford asset. Frederick the Great once said that one must understand the whole before one peers into its parts. Helping us to understand the whole is Professor Dallal's charge this afternoon. Professor Dallal will provide us with an overview of the historical development of Islamic law and may provide us with surprising insights into the relationship of Islam and Islamic law to the state and political authority. He assures us this lecture has not been delivered before. So without further ado, it is my absolute pleasure to turn over the podium to Professor Dallal. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Composition and Continuity in Sasanian Rock Reliefs

0320-07_Iran_Antiq_43_12_Thompson 09-01-2008 15:04 Pagina 299 Iranica Antiqua, vol. XLIII, 2008 doi: 10.2143/IA.43.0.2024052 COMPOSITION AND CONTINUITY IN SASANIAN ROCK RELIEFS BY Emma THOMPSON (University of Sydney, Australia) Abstract: The cliffs of Iran are adorned with rock reliefs from every period of its long history. During the years that the Sasanian dynasty ruled Iran, artists added to this collection considerably. These monuments are individual capsules of infor- mation on the general political, religious, historical and artistic milieu of the time. This paper presents a method for furthering our understanding of the Sasanian period through an analysis of the composition of each Sasanian relief. The analy- sis is based on the hypothesis that composition will serve as an indicator of artis- tic continuity and change and encode an artistic signature of sorts indicating the artists’ background and training. The initial results suggest that the reliefs of the early Sasanian period reflect the work of artists from at least two schools of art. Keywords: Sasanian, rock reliefs, composition. The kings of the Sasanian dynasty ruled Iran for over four hundred years. During the first eighty-five years of the dynasty (AD 224-309) there were seven changes of crown, many military gains and losses and thirty rock carvings were commissioned to commemorate these events. Most of these were carved in Fars, the homeland of the dynasty: eight were carved in the company of the Achaemenid tombs at Naqsh-i Rustam; six line the way to Shapur’s city at Bishapur; four were carved in the open air grotto at Naqsh- i Radjab; two were carved near Ardashir’s first city at Firuzabad and the rest were carved as single reliefs at various locations across the province of Fars: Barm-i Dilak, Sar Mashhad, Sarab-i Bahram, Guyum, Rayy, Darab- gird, and Tang-i Qandil. -

The Reliefs of Naqš-E Rostam and a Reflection on a Forgotten Relief, Iran

HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, nr 6 (2017) ISSN 2299 - 2464 Morteza KHANIPOOR (University of Tehran, Iran) Hosseinali KAVOSH (University of Zabol, Iran) Reza NASERI (University of Zabol, Iran) The reliefs of Naqš-e Rostam and a reflection on a forgotten relief, Iran Keywords: Naqš-e Rostam, Elamite, Sasanian, Relief Introduction Like other cultural materials, reliefs play their own roles in order to investigate ancient times of Iran as they could offer various religious, political, economic, artistic, cultural and trading information. Ancient artist tried to show beliefs of his community by carving religious representations on the rock. Thus, reliefs are known as useful resource to identify ancient religions and cults. As the results of several visits to Naqš-e Rostam by the author, however, a human relief was paid attention as it is never mentioned in Persian archaeological resources. The relief is highly similar to known Elamite reliefs in Fars and Eastern Khuzistan (Izeh). This paper attempts to compare the relief with many Elamite and Sasanian works and, therefore, the previous attributed date is revisited. Fig.1. Map showing archeological sites, including Naqš-e Rostam, on the Marvdasht Plain (after Schmidt, 1939: VIII ) PhD. student in Archaeology; [email protected] Assistant Professor, Faculty of Arts and Architecture; [email protected] Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology; [email protected] Page | 55 Naqš-e Rostam To the south of Iran and north of Persian Gulf, there was a state known as Pars in ancient times. This state was being occupied by different peoples such as Elamite through time resulted in remaining numerous cultural materials at different areas including Marvdasht plain1 confirming its particular significance. -

Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks History Faculty Publications and Presentations Department of History 1-1-2007 Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl Boise State University Publication Information Odahl, Charles Matson. (2007). "Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy". Connections: European Studies Annual Review, 3, 89-113. This document was originally published in Connections: European Studies Annual Review by Rocky Mountain European Scholars Consortium. Copyright restrictions may apply. Coda: Recovering Constantine's European Legacy 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Constantine the Great and Christian Imperial Theocracy Charles Matson Odahl, Boise State University1 rom his Christian conversion under the influence of cept of imperial theocracy was conveyed in contemporary art Frevelatory experiences outside Rome in A.D. 312 until (Illustration I). his burial as the thirteenth Apostle at Constantinople in Although Constantine had been raised as a tolerant 337, Constantine the Great, pagan polytheist and had the first Christian emperor propagated several Olympian of the Roman world, initiated divinities, particularly Jupiter, the role of and set the model Hercules, Mars, and Sol, as for Christian imperial theoc di vine patrons during the early racy. Through his relationship years of his reign as emperor -

Persian Royal Ancestry

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY PERSIAN ROYAL ANCESTRY Achaemenid Dynasty from Greek mythical Perses, (705-550 BC) یشنماخه یهاشنهاش (Achaemenid Empire, (550-329 BC نايناساس (Sassanid Empire (224-c. 670 INTRODUCTION Persia, of which a large part was called Iran since 1935, has a well recorded history of our early royal ancestry. Two eras covered are here in two parts; the Achaemenid and Sassanian Empires, the first and last of the Pre-Islamic Persian dynasties. This ancestry begins with a connection of the Persian kings to the Greek mythology according to Plato. I have included these kind of connections between myth and history, the reader may decide if and where such a connection really takes place. Plato 428/427 BC – 348/347 BC), was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. King or Shah Cyrus the Great established the first dynasty of Persia about 550 BC. A special list, “Byzantine Emperors” is inserted (at page 27) after the first part showing the lineage from early Egyptian rulers to Cyrus the Great and to the last king of that dynasty, Artaxerxes II, whose daughter Rodogune became a Queen of Armenia. Their descendants tie into our lineage listed in my books about our lineage from our Byzantine, Russia and Poland. The second begins with King Ardashir I, the 59th great grandfather, reigned during 226-241 and ens with the last one, King Yazdagird III, the 43rd great grandfather, reigned during 632 – 651. He married Maria, a Byzantine Princess, which ties into our Byzantine Ancestry. -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

|||GET||| European Muslims and the Secular State 1St Edition

EUROPEAN MUSLIMS AND THE SECULAR STATE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Sean McLoughlin | 9781351938518 | | | | | Islamic States and Muslim Secularism Bypractically all that remained of Muslim Spain was the southern province of Granada. Retrieved 27 June Vatican City. Sovereignty belongs to Allah alone but He has delegated it to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him as a sacred trust. February Learn how and when to remove this template message. The Times. Berkeley: University of California Press. Anti-clericalism Anticlericalism and Freemasonry Caesaropapism Clericalism Clerical fascism Confessionalism Divine rule Engaged Spirituality Feminist theology Thealogy Womanist theology Identity politics Political religion Religious anarchism Religious anti-Masonry Religious anti-Zionism Religious communism Religious humanism Religious law Religious nationalism Religious pacifism Religion and peacebuilding Religious police Religious rejection of politics Religious segregation Religious separatism Religious socialism Religious views on same-sex marriage Secularism Secular religion Separation of church and state Spiritual left State atheism State religion Theocracy Theonomy. These riots precipitated a military coup after which all political parties were banned including the Wafd and the Muslim Brotherhood. It describes the history of early European Muslims and outlines the causes and courses of twentieth-century Muslim immigration. See also: Constitution of Medina. It can be assumed that the relatively strong support for Sharia in Kyrgyzstan, reported in certain survey data, is located chiefly among this group. John L. This perception was offset by a steady stream of wars that aimed to expand Muslim rule past the caliphate's borders. Egypt's first experience of secularism started with European Muslims and the Secular State 1st edition British Occupation —the atmosphere which allowed European Muslims and the Secular State 1st edition of western ideas. -

Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

REFRAMING BORDERS: A STUDY OF THE VEIL, WRITING, AND REPRESENTATION OF THE FEMALE BODY IN THE PHOTO-BASED ARTWORK OF MONA HATOUM, SHIRIN NESHAT, AND LALLA ESSAYDI by MARYAM A M A ALWAZZAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Maryam A M A Alwazzan Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of the femaLe body In the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi This thesIs has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Master of Art HIstory degree in the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture by: Kate Mondloch ChaIr Derek Burdette Member MIchaeL Allan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018. II © 2018 Maryam A M A ALwazzan This work is lIcensed under a CreatIve Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. III THESIS ABSTRACT Maryam A M A ALwazzan Master of Arts Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture December 2018 Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of The Female Body In The Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi For a long tIme, most women beLIeved they had to choose between theIr MusLIm or Arab identIty and theIr beLIef in socIaL equaLIty of sexes. -

The Behistun Inscription and the Res Gestae Divi Augusti

Phasis 15-16, 2012-2013 Δημήτριος Μαντζίλας (Θράκη) The Behistun Inscription and the Res Gestae Divi Augusti Intertextuality between Greek and Latin texts is well known and – in recent decades – has been well studied. It seems though that common elements also appear in earlier texts, from other, mostly oriental countries, such as Egypt, Persia or Israel. In this article we intend to demonstrate the case of a Persian and a Latin text, in order to support the hypothesis of a common Indo-European literature (in addition to an Indo-European mythology and language). The Behistun Inscription,1 whose name comes from the anglicized version of Bistun or Bisutun (Bagastana in Old Persian), meaning “the place or land of gods”, is a multi-lingual inscription (being thus an equivalent of the Rosetta stone) written in three different cuneiform script extinct languages: Old Persian, Elamite (Susian), and Babylonian (Accadian).2 A fourth version is an Aramaic translation found on the 1 For the text see Adkins L., Empires of the Plain: Henry Rawlinson and the Lost Languages of Babylon, New York 2003; Rawlinson H. C., Archaeologia, 1853, vol. xxxiv, 74; Campbell Thompson R., The Rock of Behistun, In Sir J. A. Hammerton (ed.), Wonders of the Past, New York 1937, II, 760–767; Cameron G. G., Darius Carved History on Ageless Rock, National Geographic Magazine, 98 (6), December 1950, 825– 844; Rubio G., Writing in Another Tongue: Alloglottography in the Ancient Near East, in: S. Sanders (ed.), Margins of Writing, Origins of Cultures, Chicago 2007², 33–70 (= OIS, 2); Hinz W., Die Behistan-Inschrift des Darius, AMI, 7, 1974, 121-134 (translation). -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

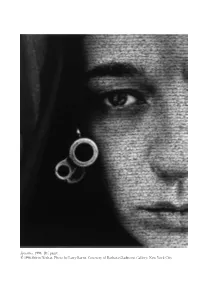

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc.