Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bright Typing Company

Tape Transcription Islam Lecture No. 1 Rule of Law Professor Ahmad Dallal ERIK JENSEN: Now, turning to the introduction of our distinguished lecturer this afternoon, Ahmad Dallal is a professor of Middle Eastern History at Stanford. He is no stranger to those of you within the Stanford community. Since September 11, 2002 [sic], Stanford has called on Professor Dallal countless times to provide a much deeper perspective on contemporary issues. Before joining Stanford's History Department in 2000, Professor Dallal taught at Yale and Smith College. Professor Dallal earned his Ph.D. in Islamic Studies from Columbia University and his academic training and research covers the history of disciplines of learning in Muslim societies and early modern and modern Islamic thought and movements. He is currently finishing a book-length comparative study of eighteenth century Islamic reforms. On a personal note, Ahmad has been terrifically helpful and supportive, as my teaching assistant extraordinaire, Shirin Sinnar, a third-year law student, and I developed this lecture series and seminar over these many months. Professor Dallal is a remarkable Stanford asset. Frederick the Great once said that one must understand the whole before one peers into its parts. Helping us to understand the whole is Professor Dallal's charge this afternoon. Professor Dallal will provide us with an overview of the historical development of Islamic law and may provide us with surprising insights into the relationship of Islam and Islamic law to the state and political authority. He assures us this lecture has not been delivered before. So without further ado, it is my absolute pleasure to turn over the podium to Professor Dallal. -

Slaves of Sleep: Nightmares of Evil Jinn in a Parallel Universe and Discovering the Meaning of Dreams Online

W9zNH [Ebook pdf] Slaves of Sleep: Nightmares of Evil Jinn in a Parallel Universe and Discovering the Meaning of Dreams Online [W9zNH.ebook] Slaves of Sleep: Nightmares of Evil Jinn in a Parallel Universe and Discovering the Meaning of Dreams Pdf Free L. Ron Hubbard audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #232342 in eBooks 2012-01-01 2012-01-01File Name: B007BS76XI | File size: 36.Mb L. Ron Hubbard : Slaves of Sleep: Nightmares of Evil Jinn in a Parallel Universe and Discovering the Meaning of Dreams before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Slaves of Sleep: Nightmares of Evil Jinn in a Parallel Universe and Discovering the Meaning of Dreams: 6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. Refreshing Adult Fantasy!By Stevehttp://www..com/Slaves-Sleep- Nightmares-Dreaming-Insomnia-ebook/dp/B008Y8CMP6/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_product_top?ie=UTF8It's refreshing to read a Fantasy that is not geared down to a young teen level. Hubbard is a master of language and an incredibly engaging writer. The two stories here included - SLAVES OF SLEEP and MASTERS OF SLEEP were written 20 years apart, from the beginning and later periods of the Author's career. And rather than being a rehash of Arabian Nights, these stories are completely original and in that fast-paced style that Hubbard is famous for. It's almost impossible to put the book down - just wonderful, clean fun and a joy to read.These books are why I read. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Two Queens of ^Baghdad Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of ^Baghdad oi.uchicago.edu Courtesy of Dr. Erich Schmidt TOMB OF ZUBAIDAH oi.uchicago.edu Two Queens of Baghdad MOTHER AND WIFE OF HARUN AL-RASH I D By NABIA ABBOTT ti Vita 0CCO' cniia latur THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO • ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu The University of Chicago Press • Chicago 37 Agent: Cambridge University Press • London Copyright 1946 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1946. Composed and printed by The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A. oi.uchicago.edu Preface HE historical and legendary fame of Harun al- Rashld, the most renowned of the caliphs of Bagh dad and hero of many an Arabian Nights' tale, has ren dered him for centuries a potent attraction for his torians, biographers, and litterateurs. Early Moslem historians recognized a measure of political influence exerted on him by his mother Khaizuran and by his wife Zubaidah. His more recent biographers have tended either to exaggerate or to underestimate the role of these royal women, and all have treated them more or less summarily. It seemed, therefore, desirable to break fresh ground in an effort to uncover all the pertinent his torical materials on the two queens themselves, in order the better to understand and estimate the nature and the extent of their influence on Harun and on several others of the early cAbbasid caliphs. As the work progressed, first Khaizuran and then Zubaidah emerged from the privacy of the royal harem to the center of the stage of early cAbbasid history. -

2256 Inventory 4.Pdf

The Robert Bloch Collection, Acc. ~2256-89-0]-27 Page 11 Box ~ (continueo) Periooicals (continueol: F~ntastic Adyentutes: Vol. 5 (No.8), Allg. 194]: "You Can't Kio Lefty Feep", pp.148-166; "Fairy Tale" under the name Tarleton Fiske, pp.184-202; biographical note on Tarleton Fiske, p.203. Vol. 5 (No.9), Oct. 194]: "A Horse On Lefty Feep", pp. 86-101; "Mystery Of The Creeping Underwear" under the name Tarleton FIske, pp.132-146. Vol. 6 (No.1), Feb. 1944; "Lefty Feep's ~l:abian Nightmare", pp.178-192. Vol. 6 (No. 2), ~pr. 1944: "Lefty Feep Does Time", pp. 156-1'15. Vol. 7 (No.2), Apr. IH5: "Lefty Feep Gets Henpeckeo", 1'1'.116-131. Vol. 6 (No.3), July 1946: "Tree's A Cro"d", pp.74-90. Vol. 9 (No. 51, sept. 1947: "The Mad Scientist", pp. 108-124. Vol. 12 (No.3), Mar. 1950: "Girl From Mars", pp.28-33. Vol. 12 (No.7), July 1950: "End Of YOUl: Rope", 1'p.l10- 124. Vol. 12 (No. S), Aug. 1950: "The Devil With Youl", pp. 8-68. Vol. 13 (No.7), July 1951: "The Dead Don't Die", pp. 8-54; biogl;aphical note, pp.2, 129-130. Fantastic Monsters Of The F11ms, Vol. 1 (No.1), 1962: "Black Lotus", p.10-21, 62. Fantastic Uniyel;se: Vol. 1 (No.6), May 1954: "The Goddess Of Wisdom", pp. 117-128. Vol. 4 (No, 6), Jan. 1956: "You Got To Have Brains", pp .112-120. Vol. 5 (No.6), July 1956: "Founoing Fathel:s", pp.34- Vol. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

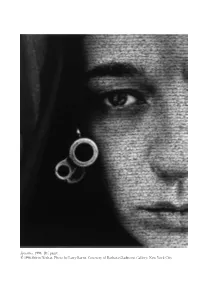

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 2 (2010) Jan W. Żelazny Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków The legend of Shirin in Syriac sources. A warning against caesaropapism? Why was Syriac Christianity not an imperial Church? Why did it not enter into a relationship with the authorities? This can be explained by pointing to the political situation of that community. I think that one of the reasons was bad experiences from the time of Chosroes II. The Story of Chosroes II The life of Chosroes II Parviz is a story of rise and fall. Although Chosroes II became later a symbol of the power of Persia and its ancient independence, he encountered numerous difficulties from the very moment he ascended the throne. Chosroes II took power in circumstances that today remain obscure – as it was frequently the case at the Persian court – and was raised to the throne by a coup. The rebel was inspired by an attempt of his father, Hormizd IV, to oust one of the generals, Bahram Cobin, which provoked a powerful reaction among the Persian aristocracy. The question concerning Chosroes II’s involvement in the conspiracy still remains unanswered; however, Chosroes II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father. Soon after, Hormizd IV died in prison in ambiguous circumstances. The Arabic historian, al-Tabari, claimed that Chosroes was oblivious of the rebellion. However, al-Tabari works were written several centuries later, at a time when the legend of the shah was already deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people. -

The False Caliph ROBERT G

The False Caliph ROBERT G. HAMPSON 1 heat or no heat, the windows have to be shut. nights like this, the wind winds down through the mountain passes and itches the skin on the backs of necks: anything can happen. 2 voices on the radio drop soundless as spring rain into the murmur of general conversation. his gloved hands tap lightly on the table-top as he whistles tunelessly to himself. his partner picks through a pack of cards, plucks out the jokers and lays down a mat face down in front of him. 285 286 The 'Arabian Nights' in English Literature the third hones his knife on the sole of his boot: tests its edge with his thumb. 3 Harry can't sleep. Mezz and the boys, night after night, have sought means to amuse him to cheat the time till dawn brings the tiredness that finally takes him. but tonight everything has failed. neither card-tricks nor knife-tricks - not even the prospect of nocturnal adventures down in the old town has lifted his gloom. they're completely at a loss. then the stranger enters: the same build the same face the same dress right down to the identical black leather gloves on the hands The False Caliph 287 which now tap contemptuously on the table while he whistles tunelessly as if to himself. Appendix W. F. Kirby's 'Comyarative Table of the Tales in the Principal Editions o the Thousand and One Nights' from fhe Burton Edition (1885). [List of editions] 1. Galland, 1704-7 2. Caussin de Perceval, 1806 3. -

Fantasy Commentator 20

...covering the field of imaginative literature... A. Langley Searles editor and publisher contributing editors; William H. Evans, Thyril L. Ladd, Sam Moskowitz, Matthew H. Onderdonk, Darrell C. Richardson, Richard Witter Vol. II, No. 8 --- 0O0--- Fall 1948 CONTENTS T EDITORIAL: This-'n'-That A. Langley Searles 260 ARTICLES: The "Polaris" Trilogy Richard Witter 261 An Analytical Approach to the George T. Wetzel 265 Supernatural-Horror Tale In a Glass---- Darkly Matthew H. Onderdonk 267 Fantasy in the Popular Magazine William H. Evans 273 The Immortal Storm (part 13) Sam Moskowitz 284 Talbot Mundy: Oriental Mystic Darrell C. Richardson 290 Indexes to Volume Tito of Fantasy Commentator 294 VERSE: Beyond the Shadovz Genevieve K. Stevens 266 REGULAR FEATURES: Book Reviews: Phi 11 pot t s ‘ Lycanthrope Marion Zimmer * 271 Merritt's w Bok's Black Wheel A. Langley Searles 282 Tips on Tales Thyril L. Ladd 264 Thumbing the Munsey Files William H. Evans 292 This is the twentieth number of Fantasy Commentator, an amateur, non-profit . periodical of limited circulation appearing at quarterly intervals. Subscription rates: 25^ per copy, five issues for $1, This magazine does not exchange sub scriptions with other publications except by specific arrangement. All opinions t expressed herein are the individual contributors' own, and do not necessarily re flect those of staff members. Although Fantasy Commentator publishes no fiction, manuscripts dealing with any phase of imaginative literature are always welcome. Please address communications to the editor at 7 East 235th St., New York 66, N.Y. copyright 1948 by A. Langley Searles 260 FANTASY COMMENTATOR THIS-'N'-THAT Again we return to the task of listing all fantasy fiction that has appeared in 1948 since our last issue; world of the jinns, described with con Ashton, Francis: Alas, That Great City siderably more blood than art, (Dakers, 9/6). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Narrative and Iranian Identity in the New Persian Renaissance and the Later Perso-Islamicate World DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Conrad Justin Harter Dissertation Committee: Professor Touraj Daryaee, Chair Professor Mark Andrew LeVine Professor Emeritus James Buchanan Given 2016 © 2016 Conrad Justin Harter DEDICATION To my friends and family, and most importantly, my wife Pamela ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CURRICULUM VITAE vi ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 2: Persian Histories in the 9th-12th Centuries CE 47 CHAPTER 3: Universal History, Geography, and Literature 100 CHAPTER 4: Ideological Aims and Regime Legitimation 145 CHAPTER 5: Use of Shahnama Throughout Time and Space 192 BIBLIOGRAPHY 240 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Map of Central Asia 5 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to all of the people who have made this possible, to those who have provided guidance both academic and personal, and to all those who have mentored me thus far in so many different ways. I would like to thank my advisor and dissertation chair, Professor Touraj Daryaee, for providing me with not only a place to study the Shahnama and Persianate culture and history at UC Irvine, but also with invaluable guidance while I was there. I would like to thank my other committee members, Professor Mark LeVine and Professor Emeritus James Given, for willing to sit on my committee and to read an entire dissertation focused on the history and literature of medieval Iran and Central Asia, even though their own interests and decades of academic research lay elsewhere. -

Voicing the Voiceless: Feminism and Contemporary Arab Muslim Women's Autobiographies

VOICING THE VOICELESS: FEMINISM AND CONTEMPORARY ARAB MUSLIM WOMEN'S AUTOBIOGRAPHIES Taghreed Mahmoud Abu Sarhan A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2011 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Vibha Bhalla Graduate Faculty Representative Radhika Gajjala Erin Labbie iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor Arab Muslim women have been portrayed by the West in general and Western Feminism in particular as oppressed, weak, submissive, and passive. A few critics, Nawar al-Hassan Golley, is an example, clarify that Arab Muslim women are not weak and passive as they are seen by the Western Feminism viewed through the lens of their own culture and historical background. Using Transnational Feminist theory, my study examines four autobiographies: Harem Years By Huda Sha’arawi, A Mountainous Journey a Poet’s Autobiography by Fadwa Tuqan, A Daughter of Isis by Nawal El Saadawi, and Dreams of Trespass, Tales of a Harem Girlhood by Fatima Mernissi. This study promises to add to the extant literature that examine Arab Muslim women’s status by viewing Arab women’s autobiographies as real life stories to introduce examples of Arab Muslim women figures who have effected positive and significant changes for themselves and their societies. Moreover, this study seeks to demonstrate, through the study of select Arab Muslim women’s autobiographies, that Arab Muslim women are educated, have feminist consciousnesses, and national figures with their own clear reading of their own religion and culture, more telling than that of the reading of outsiders. -

The Gnostic L. Ron Hubbard: Was He Influenced by Aleister Crowley?

$ The Journal of CESNUR $ The Gnostic L. Ron Hubbard: Was He Influenced by Aleister Crowley? Massimo Introvigne CESNUR (Center for Studies on New Religions) [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scientology was defined by its founder himself, L. Ron Hubbard, as a “Gnostic religion.” In 1969, however, a Trotskyist Australian journalist and an opponent of Scientology, Alex Mitchell, disclosed in a Sunday Times article that Hubbard had been involved, in 1945–46, in the activities of California’s Agapé Lodge of the Ordo Templi Orientis, an occult organization led by British magus Aleister Crowley. The article generated a cottage industry of exposés criticizing Hubbard as having been a member of a “black magic” organization. Some scholars also believe Hubbard to have been influenced by Crowley in his subsequent writings about Dianetics and Scientology. While conflicting narratives exist about why exactly Hubbard participated in the activities of the Agapé Lodge and his leader, the rocket scientist Jack Parsons, the article argues that Hubbard researched magic well before 1945, came to conclusions about the role of magic in Western culture that are largely shared by 21st century scholars, and created with Scientology a system that is inherently religious rather than magic. KEYWORDS: Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard, Babalon Working, Aleister Crowley, Jack Parsons, John Whiteside Parsons, O.T.O., Agapé Lodge. Scientology and Gnosticism Some weeks ago, I was visited by a leading Chinese scholar of religion, Zhang Xinzhang from Zhejiang University. Zhang is a scholar of Gnosticism and a critic of movements the Chinese government identifies as xie jiao (“heterodox teachings,” sometimes translated, less accurately, as “evil cults”).