Bright Typing Company

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maliki School

Dr. Javed Ahmed Qureshi School of Studies in Law Jiwaji University GWALIOR - 474 011 (MP), INDIA LAW B.A.LL.B. IV-SEM MUSLIM LAW BY Dr. JAVED AHMED QURESHI DATE- 04-04-2020 MALIKI SCHOOL Maliki school is one of the four schools of fiqh or religious law within Sunni Islam. It is the second largest of the four schools, followed by about 25% Muslims, mostly in North Africa and West Africa. This school is not a sect, but a school of jurisprudence. Technically, there is no rivalry or competition between members of different madrasas, and indeed it would not be unusual for followers of all four to be found in randomly chosen American or European mosques. This school derives its name from its founder Imam Malik-bin-Anas. It originates almost to the same period as the Hanafi school but it flourished first in the city of Madina. Additionally, Malik was known to have used ray (personal opinion) and qiyas (analogy). This school is derives from the work of Imam Malik. It differs in different sources from the three other schools of rule which use it for derivation of regimes. All four schools use the Quran as the primary source, followed by Prophet Muhammad's transmitted as hadith (sayings), ijma (consensus of the scholars or Muslims) and Qiyas (analogy).In addition, the School of Maliki uses the practice of the people of Madina (Amal Ahl al-Madina) as a source. While the Hanafi school relies on Ijma (interpretations of jurists), the Maliki school originates from Sunna and Hadis. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

Interpreting the Qur'an and the Constitution

INTERPRETING THE QUR’AN AND THE CONSTITUTION: SIMILARITIES IN THE USE OF TEXT, TRADITION, AND REASON IN ISLAMIC AND AMERICAN JURISPRUDENCE Asifa Quraishi* INTRODUCTION Can interpreting the Qur’an be anything like interpreting the Constitution? These documents are usually seen to represent overwhelming opposites in our global legal and cultural landscapes. How, after all, can there be any room for comparison between a legal system founded on revelation and one based on a man-made document? What this premise overlooks, however, is that the nature of the founding legal text tells only the beginning of the story. With some comparative study of the legal cultures that formed around the Qur’an and the Constitution, a few common themes start to emerge, and ultimately it turns out that there may be as much the same as is different between the jurisprudence of Islam and the United States. Though set against very different cultures and legal institutions, jurists within Islamic law have engaged in debates over legal interpretation that bear a striking resemblance to debates in the world of American constitutional theory.1 We will here set these debates next to * Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. The author wishes to thank Frank Vogel and Jack Balkin for their support and advice in the research that contributed to this article, and Suzanne Stone for the opportunity to be part of a stimulating conference and symposium. 1 Positing my two fields as “Islamic” and “American” invokes a host of potential misunderstandings. First, these are obviously not mutually exclusive categories, most vividly illustrated by the significant population of American Muslims, to which I myself belong. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

Reframing Borders: a Study of the Veil, Writing, and Representation of the Female Body in the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum

REFRAMING BORDERS: A STUDY OF THE VEIL, WRITING, AND REPRESENTATION OF THE FEMALE BODY IN THE PHOTO-BASED ARTWORK OF MONA HATOUM, SHIRIN NESHAT, AND LALLA ESSAYDI by MARYAM A M A ALWAZZAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the UniversIty of Oregon in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Maryam A M A Alwazzan Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of the femaLe body In the Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi This thesIs has been accepted and approved in partIaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the Master of Art HIstory degree in the Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture by: Kate Mondloch ChaIr Derek Burdette Member MIchaeL Allan Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden VIce Provost and Dean of the Graduate School OriginaL approvaL sIgnatures are on fiLe wIth the UniversIty of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2018. II © 2018 Maryam A M A ALwazzan This work is lIcensed under a CreatIve Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. III THESIS ABSTRACT Maryam A M A ALwazzan Master of Arts Department of The HIstory of Art and Architecture December 2018 Title: ReframIng Borders: A Study of the VeIL, WritIng and RepresentatIon of The Female Body In The Photo-Based Artwork of Mona Hatoum, Shirin Neshat and LaLLa Essaydi For a long tIme, most women beLIeved they had to choose between theIr MusLIm or Arab identIty and theIr beLIef in socIaL equaLIty of sexes. -

Between Two Worlds: an Interview with Shirin Neshat

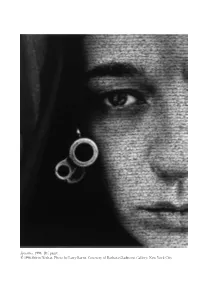

Speechless, 1996. RC print. © 1996 Shirin Neshat. Photo by Larry Barns. Courtesy of Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York City. Between Two Worlds: An Interview with Shirin Neshat Scott MacDonald A native of Qazvin, Iran, Shirin Neshat finished high school and attended college in the United States and once the Islamic Revolution had transformed Iran, decided to remain in this country. She now lives in New York City, where she is represented by the Barbara Gladstone Gallery. In the mid-1990s, Neshat became known for a series of large photographs, “Women of Allah,” which she designed, directed (not a trained photogra- pher, she hired Larry Barns, Kyong Park, and others to make her images), posed for, and decorated with poetry written in Farsi. The “Women of Allah” photographs provide a sustained rumination on the status and psyche of women in traditional Islamic cultures, using three primary elements: the black veil, modern weapons, and the written texts. In each photograph Neshat appears, dressed in black, sometimes covered completely, facing the camera, holding a weapon, usually a gun. The texts often appear to be part of the photographed imagery. The photographs are both intimate and confrontational. They reflect the repressed status of women in Iran and their power, as women and as Muslims. They depict Neshat herself as a woman caught between the freedom of expression evi- dent in the photographs and the complex demands of her Islamic heritage, in which Iranian women are expected to support and sustain a revolution Feminist Studies 30, no. 3 (Fall 2004). © 2004 by Feminist Studies, Inc. -

The Legend of Shirin in Syriac Sources. a Warning Against Caesaropapism?

ORIENTALIA CHRISTIANA CRACOVIENSIA 2 (2010) Jan W. Żelazny Pontifical University of John Paul II in Kraków The legend of Shirin in Syriac sources. A warning against caesaropapism? Why was Syriac Christianity not an imperial Church? Why did it not enter into a relationship with the authorities? This can be explained by pointing to the political situation of that community. I think that one of the reasons was bad experiences from the time of Chosroes II. The Story of Chosroes II The life of Chosroes II Parviz is a story of rise and fall. Although Chosroes II became later a symbol of the power of Persia and its ancient independence, he encountered numerous difficulties from the very moment he ascended the throne. Chosroes II took power in circumstances that today remain obscure – as it was frequently the case at the Persian court – and was raised to the throne by a coup. The rebel was inspired by an attempt of his father, Hormizd IV, to oust one of the generals, Bahram Cobin, which provoked a powerful reaction among the Persian aristocracy. The question concerning Chosroes II’s involvement in the conspiracy still remains unanswered; however, Chosroes II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father. Soon after, Hormizd IV died in prison in ambiguous circumstances. The Arabic historian, al-Tabari, claimed that Chosroes was oblivious of the rebellion. However, al-Tabari works were written several centuries later, at a time when the legend of the shah was already deeply rooted in the consciousness of the people. -

Akademia Baru Law Foundation Study of Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal's

Penerbit Akademia Baru Journal of Advanced Research Design ISSN (online): 2462-1943 | Vol. 21, No. 1. Pages 1-5, 2016 Law Foundation Study of Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal’s Thought in Characteristics of Allah *,1,a 2,b 2 1,c 1,d R. L. Sinaga , I. Ishak , M. Ahmad , M. Irwanto and H. Widya 1Department of Electrical Engineering, Institut Teknologi Medan (ITM) Medan, Indonesia 2College of Art and Science, Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM) Kedah, Malaysia a,* [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract –Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal is very famous in traditions collector of Prophet Muhammad, but there are statements related to characteristics of Allah that stated by him. Therefore, it is very important to understand Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal’s thought in characteristics of Allah. It is history study that explains a short biography of Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal and his statements about characteristics of Allah. Based on the literature study that Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal believes the characteristics of Allah are based on the Koran and collection of traditions of Prophet Muhammad. The characteristics of Allah believed by Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal are suitable to Ahli Sunnah wal Jamaah. Copyright © 2016 Penerbit Akademia Baru - All rights reserved. Keywords: Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal, faith, tawhid, characteristics of Allah 1.0 INTRODUCTION Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal was born in Baghdad in Rabiulawal , 164 H/ 780 M, when the government of Bani Abbasiyah was led by Muhammad al-Mahdi [1, 2]. This case is also stated by [3] who explained that Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal was born on a not strange date for our ear, it was on Rabiulawal , exactly in one hundred sixty four from Hejira year of Prophet Muhammad. -

Usul Al Fiqh

RULE OF LAW IN THE EXPLORATION AND USE OF OUTER SPACE Islamic Legal Perspective: Foundational Principles and Considerations Hdeel Abdelhady, MassPoint and Strategy Advisory PLLC Rule of Law: Core Issues, Foundational Islamic Principles and Paradigms Elements (General) Islamic Paradigms ¨ Space Exploration and ¨ Qur’an/Islamic law on Use scientific endeavor ¤ Purpose of Exploration? ¤ Encouraged ¤ Sovereignty right? ¤ “Balance” ¤ Property right? ¤ Legal Rulings ¤ Conduct in Space ¤ Governance ¨ Prohibited purposes? ¨ Products/Tools of Space ¨ Property Rights (general) Exploration ¨ Objectives of Exploration ¤ Intellectual Property (permissibility) ¤ Tangible Property Islam: Legal and Jurisprudential Framework* Islam Shari’ah Qur’an, Sunnah, Ijma, Qiyas Jurisprudence (substantive law Fiqh and method) (usul al fiqh) Fiqh al-Mu’amalat Fiqh al-Ibadat Fiqh al-Jinayat (interpersonal relations) (ritual worship) (criminal law) Commercial Transactions Property (tangible, intellectual) *This is a simplified visualization. Islamic Context: Religion, Morality, Law Inextricable “’Law . in any sense in which a Western lawyer would recognize the term, is . one of several inextricably combined elements thereof. Sharī’a . which is commonly rendered as ‘law’ is, rather, the ‘Whole Duty of Man . [A]ll aspects of law; public and private hygiene; and even courtesy and good manners are all part and parcel of the Sharī’a, a system which sometimes appears to be rigid and inflexible; at other to be imbued with dislike of extremes, that spirit of reasonable compromise which was part of the Prophet’s own character.’” -S.G. Vesey Fitzgerald, Nature and Sources of the Sharī’a (1955), at 85-86. Islamic Law: Sources, Sunni Schools Primary Sources Four Prevailing “Schools” of Sunni Islamic Law ¨Qur’an ¨ Hanafi (Abu Hanifa Al No’man, ¨Sunnah 699-787) ¨ Maliki (Malik ibn Anas Al Asbahi, 710-795) Secondary Sources ¨ Shafi’i (Muhammad ibn Idris ibn ¨Qiyas Abbas ibn Uthman ibn Al- Shafi’i, 768-820) ¨Ijma ¨ Hanbali (Ahmed ibn Hanbal, 780- 855). -

Dramatis Personae •

Dramatis Personae • Note: all dates are approximate. ALEXANDER THE GREAT (356– 323 bc). Macedonian ruler who, af- ter invading Central Asia in 329 bc, spent three years in the region, establishing or renaming nine cities and leaving behind the Bactrian Greek state, headquartered at Balkh, which eventually ruled territo- ries extending into India. Awhad al- Din ANVARI (1126– 1189). Poet and boon companion of Sultan Sanjar at Merv who, boasting of his vast knowledge, wrote that, “If you don’t believe me, come and test me. I am ready.” Nizami ARUDI. Twelfth- century Samarkand- born poet and courtier of the rulers of Khwarazm and of Ghor, and author of Four Discourses, in which he argued that a good ruler’s intellectual stable should include secretaries, poets, astrologers, and physicians. Abu Mansur Ali ASADI. Eleventh- century poet from Tus and follower of Ferdowsi. Working at a court in Azerbaijan, Asadi versified The Epic of Garshasp (Garshaspnameh), which ranks second only to Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh among Persian epic poems. Farid al- Din ATTAR (1145– 1221). Pharmacist and Sufi poet from Nishapur, who combined mysticism with the magic of the story- teller’s art. His Conference of the Birds is an allegory in which the birds of the world take wing in search of Truth, only to find it within themselves. Yusuf BALASAGUNI (Yusuf of Balasagun). Author in 1069 of the Wisdom of Royal Glory, a guide for rulers and an essay on ethics. Written in a Turkic dialect, Yusuf’s volume for the first time brought a Turkic language into the mainstream of Mediterranean civilization and thought. -

Civilization in the Era of Harun Al-Rashid: the Synergy of Islamic Education and Economics in Building the Golden Age of Islam

Review of Islamic Economics and Finance Volume 3 No 2 December 2020 Civilization in the Era of Harun Al-Rashid: The Synergy of Islamic Education and Economics in Building The Golden Age of Islam Anto Apriyanto1 Muhammadiyah Institute of Business, Bekasi E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: This article discusses the Islamic civilization's description during the leadership of the Caliph Harun Al-Rashid of the Abbasid Daula, which was progressing rapidly. His triumph was inseparable from the Islamic education system's synergy role. The Islamic economic system was implemented and became a characteristic of that time. Historical records show that the Islamic civilization at that time succeeded in bringing and showing the world that Islam was a superpower that could not be taken lightly by its reign of more than 5 (five) centuries. One of the indicators of the triumph of Islamic civilization is an indicator in the rapidly developing economy, be it agriculture, trade, or industry, due to the rapid development of the world of education and research. At that time, education got much attention from the state. However, education cannot succeed without economic support. Therefore, the state gives primary attention to the people's welfare, especially those related to the education component, namely students, educators, education funding, educational facilities, and educational tools. So it is not an exaggeration if the early period of Abbasid leadership encouraged the birth of The Golden Age of Islam. Keywords: Islamic Civilization; Abbasids; Harun Al-Rashid; Islamic education; Islamic economics; The Golden Age of Islam INTRODUCTION History records that before the West succeeded in leading world civilization with its advances in all fields, Islam had already started it. -

Two Abbasid Trials: Ahmad Ibn Hanbal and Hunayn B. Ishāq

TWO ABBASE) TRIALS: AHMAD fflN HANBAL AND HUNAYN B. ISHÀQ1 Michael COOPERSON University of California, Los Angeles I. hi 220/835, the 'Abbasid caMph al-Mu'tasim presided over a disputation between the hadîth-scholar Ibn Hanbal and a group of court theologians. Ibn Hanbal had refused assent to the doctrine of the createdness of the Qur'an, a doctrine which the previous caliph, al-Ma'mün, had declared orthodox eight years before. Spared execution by the death of al-Ma'mûn, Ibn Hanbal languished in prison at Baghdad until a well-meaning relative persuaded the authorities to let him defend himself. The ensuing disputation took place before the caMph al-Mu'tasim, who did not share al-Ma'mùn's penchant for theology. In partisan accounts, each side claims to have won the debate, or at least to have exposed the incoherence of the other position. Yet the caliph does not appear to have decided the case on its intellectual merits. Rather, he merely agreed with his advisors that Ibn Hanbal's stubbornness was tantamount to defiance of the state. Even so, he did not agree to execute him, or return him to prison. Instead, he ordered him flogged and then released. Modem scholarship has only recently called the conventional account of Ibn Hanbal's release into question. ^ The early Hanbalî accounts claim that their imam's fortitude won the day. ^ Realizing that Ibn Hanbal would allow himself to be beaten to death rather than capitulate, al-Mu'tasim let him go, an account which later sources supplement with elaborate hagiographie fabrications.