2013-Azetouri-043

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rubai (Quatrain) As a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 2, Issue - 4, Apr – 2018 UGC Approved Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Impact Factor: 3.449 Publication Date: 30/04/2018 Rubai (Quatrain) as a Classical Form of Poetry in Persian Literature Ms. Mina Qarizada Lecturer in Samangan Higher Education, Samangan, Afghanistan Master of Arts in English, Department of English Lovely Professional University, Punjab, India Email – [email protected] Abstract: Studying literature, including poetry and prose writing, in Afghanistan is very significant. Poetry provides some remarkable historical, cultural, and geographical facts and its literary legacy of a particular country. Understanding the poetic forms is important in order to understand the themes and the styles of the poetry of the poets. All the Persian poets in some points of the time composed in the Rubai form which is very common till now among the past and present generation across Afghanistan. This paper is an overview of Rubai as a classical form of Poetry in Persian Literature. Rubai has its significant role in the society with different stylistic and themes related to the cultural, social, political, and gender based issues. The key features of Rubai are to be eloquent, spontaneous and ingenious. In a Rubai the first part is the introduction which is the first three lines that is the sublime for the fourth line of the poem. It represents the idea if sublet, pithy and clever. It also represents the poets’ literary works, poetic themes, styles, and visions. Key Words: Rubai, Classic, Poetry, Persian, Literature, Quatrain, 1. INTRODUCTION: Widespread geography of Persian speakers during the past centuries in the history of Afghanistan like many other countries, it can be seen and felt that only great men were trained in the fields of art and literature. -

Irreverent Persia

Irreverent Persia IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES Poetry expressing criticism of social, political and cultural life is a vital integral part of IRREVERENT PERSIA Persian literary history. Its principal genres – invective, satire and burlesque – have been INVECTIVE, SATIRICAL AND BURLESQUE POETRY very popular with authors in every age. Despite the rich uninterrupted tradition, such texts FROM THE ORIGINS TO THE TIMURID PERIOD have been little studied and rarely translated. Their irreverent tones range from subtle (10TH TO 15TH CENTURIES) irony to crude direct insults, at times involving the use of outrageous and obscene terms. This anthology includes both major and minor poets from the origins of Persian poetry RICCARDO ZIPOLI (10th century) up to the age of Jâmi (15th century), traditionally considered the last great classical Persian poet. In addition to their historical and linguistic interest, many of these poems deserve to be read for their technical and aesthetic accomplishments, setting them among the masterpieces of Persian literature. Riccardo Zipoli is professor of Persian Language and Literature at Ca’ Foscari University, Venice, where he also teaches Conceiving and Producing Photography. The western cliché about Persian poetry is that it deals with roses, nightingales, wine, hyperbolic love-longing, an awareness of the transience of our existence, and a delicate appreciation of life’s fleeting pleasures. And so a great deal of it does. But there is another side to Persian verse, one that is satirical, sardonic, often obscene, one that delights in ad hominem invective and no-holds barred diatribes. Perhaps surprisingly enough for the uninitiated reader it is frequently the same poets who write both kinds of verse. -

Dessert Menu

MADO MENU DESSERTS From Karsambac to Mado Ice cream: Flavor’s Journey throughout the History From Karsambac to Mado Ice-cream: Flavors’ Journey throughout the History Mado Ice-cream, which has earned well-deserved fame all over the world with its unique flavor, has a long history of 300 years. This is the history of the “step by step” transformation of a savor tradition called Karsambac (snow mix) that entirely belongs to Anatolia. Karsambac is made by mixing layers of snow - preserved on hillsides and valleys via covering them with leaves and branches - with fruit extracts in hot summer days. In time, this mixture was enriched with other ingredients such as milk, honey, and salep, and turned into the well-known unique flavor of today. The secret of the savor of Mado Ice-cream lies, in addition to this 300 year-old tradition, in the climate and geography where it is produced. This unique flavor is obtained by mixing the milk of animals that are fed on thyme, milk vetch and orchid flowers on the high plateaus on the hillsides of Ahirdagi, with sahlep gathered from the same area. All fruit flavors of Maras Ice-cream are also made through completely natural methods, with pure cherries, lemons, strawberries, oranges and other fruits. Mado is the outcome of the transformation of our traditional family workshop that has been ice-cream makers for four generations, into modern production plants. Ice-cream and other products are prepared under cutting edge hygiene and quality standards in these world-class modern plants and are distributed under necessary conditions to our stores across Turkey and abroad; presented to the appreciation of your gusto, the esteemed gourmet. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

38 the Impact of the Construction of The

International Journal of Scientific Research and Modern Education (IJSRME) Impact Factor: 7.137, ISSN (Online): 2455 – 5630 (www.rdmodernresearch.com) Volume 4, Issue 1, 2019 THE IMPACT OF THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE TRANSCASPIAN RAILWAY ON THE ECONOMIC AND TRADE RELATIONS BETWEEN RUSSIA AND BUKHARA A. Gafurov Professor of the Department, Social-Humanitarian Sciences and Physical Training Cite This Article: A. Gafurov, “The Impact of the Construction of the Transcaspian Railway on the Economic and Trade Relations between Russia and Bukhara”, International Journal of Scientific Research and Modern Education, Volume 4, Issue 1, Page Number 38-39, 2019. Copy Right: © IJSRME, 2019 (All Rights Reserved). This is an Open Access Article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract: The article focuses on the role of the Trans-Caspian (Central Asian) Railroad to increase the trade turnover between Russia and Bukhara in the late XIX-early XX centuries. Key Words: Trans-Caspian Railway, Kagan, Cotton, Factories, Trade, Sale, Cotton Cleaning Machines & Pressing The Impact of the Construction of the Transcaspian Railway on the Economic and Trade Relations between Russia and Bukhara: The transformation of Turkestan into a colony, the Bukhara and Khiva khanates into semi-colony opened wide opportunities for the penetration of Russian industrial goods to Central Asia and export of local raw materials to Russia. But traditional historical caravan transportations could not ensure the uninterrupted delivery of a growing scale of goods turnover from one end to the other and back. Of great importance in resolving this matter was the construction of the first major railway line, Transcaspian, which connected Russian industry with Central Asian raw materials and sales market. -

Vulnerability of Pastoral Nomads to Multiple Socio-Political and Climate Stresses – the Shahsevan of Northwest Iran

Pastoralism under Pressure: Vulnerability of Pastoral Nomads to Multiple Socio-political and Climate Stresses – The Shahsevan of Northwest Iran Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Asghar Tahmasebi aus Tabriz/Iran Bonn 2012 Angefertigt mit Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienstes (DAAD) 1. Referent: Prof.Dr. Eckart Ehlers 2. Referent: Prof.Dr. Winfried Schenk Tag der Promotion: June 25, 2012 Erscheinungsjahr: 2012 Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................. i List of maps ..................................................................................................................................... iv List of tables .................................................................................................................................... iv List of figures ................................................................................................................................... vi List of Persian words ....................................................................................................................... vii Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... -

The Great Empires of Asia the Great Empires of Asia

The Great Empires of Asia The Great Empires of Asia EDITED BY JIM MASSELOS FOREWORD BY JONATHAN FENBY WITH 27 ILLUSTRATIONS Note on spellings and transliterations There is no single agreed system for transliterating into the Western CONTENTS alphabet names, titles and terms from the different cultures and languages represented in this book. Each culture has separate traditions FOREWORD 8 for the most ‘correct’ way in which words should be transliterated from The Legacy of Empire Arabic and other scripts. However, to avoid any potential confusion JONATHAN FENBY to the non-specialist reader, in this volume we have adopted a single system of spellings and have generally used the versions of names and titles that will be most familiar to Western readers. INTRODUCTION 14 The Distinctiveness of Asian Empires JIM MASSELOS Elements of Empire Emperors and Empires Maintaining Empire Advancing Empire CHAPTER ONE 27 Central Asia: The Mongols 1206–1405 On the cover: Map of Unidentified Islands off the Southern Anatolian Coast, by Ottoman admiral and geographer Piri Reis (1465–1555). TIMOTHY MAY Photo: The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. The Rise of Chinggis Khan The Empire after Chinggis Khan First published in the United Kingdom in 2010 by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX The Army of the Empire Civil Government This compact paperback edition first published in 2018 The Rule of Law The Great Empires of Asia © 2010 and 2018 Decline and Dissolution Thames & Hudson Ltd, London The Greatness of the Mongol Empire Foreword © 2018 Jonathan Fenby All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced CHAPTER TWO 53 or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, China: The Ming 1368–1644 including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

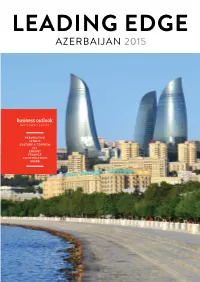

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

De-Persifying Court Culture the Khanate of Khiva’S Translation Program

10 De-Persifying Court Culture The Khanate of Khiva’s Translation Program Marc Toutant Despite the expansion of Turkish-speaking populations and the efforts of several Turko-Mongol dynasties to promote the use of Chaghatai Turkish after the thir- teenth-century era of the Mongol Empire, Persian remained a favored language all over Central Asia in chanceries and belles-lettres till as late as the nineteenth century.1 Only a small proportion of the literature created in Central Asia was in Chaghatai Turkish (hereafter simply called Turkish), and Persian was the ma- jor medium of learned expression in all parts of the region, as Devin DeWeese’s chapter 4 in this volume reminds us. And as Alfrid Bustanov’s chapter 7 shows, even in distant Tatar villages of the Russian Empire, where there were no native speakers of Persian, the classics of Persian ethical literature were widely copied in local madrasas, where some students even tried to compose their own literary works in Persian. Nevertheless, the status of Persian as lingua franca did not remain unchal- lenged in Central Asia. Over the course of the fifteenth century, cultural patronage under the Timurid rulers brought about the composition of numerous Turkish texts in diverse fields of learning. At the court of the last great Timurid ruler, Husayn Bayqara (r. 1469–70, 1470–1506), one of the most important corpora of Central Asian Turkish literature was written by Mir ‘Ali Shir Nawa’i (1441–1501). Albeit largely based on Persian models, the works of Nawa’i can be regarded as an attempt to forge a culture that was specific to his Turkophone audience. -

Klublarin Lisenziyaşdirilmasi Üzrə Hesabat 2016

KLUBLARIN LİSENZİYAŞDIRILMASI BİZ BİRLİKDƏ GÜCLÜYÜK! ÜZRƏ HESABAT 2016 Ön söz Ənənəvi olaraq, AFFA-nın Klubların Lisenziyalaşdırılması üzrə III hesabatını Sizə Bu hesabat 2015-2016-cı il Premyer Liqa mövsümünü və 2015-ci maliyyə təqdim edirik. ilini əhatə etməklə 30.04.2016-ci il tarixinə mövcud olan vəziyyəti əks etdirir. Hesabatda əks olunan göstəricilər klubların nailiyyətləri ilə bərabər, müəyyən İnanırıq ki, hesabatda əks olunmuş məlumatlar AFFA, PFL, klublar və bütün çatışmazlıqları da əhatə edir. futbol ailəsinin üzvləri üçün maraqlı olacaq. Hesabatda lisenziyalaşdırma ilə bağlı müxtəlif məlumatlar və müqayisəedici göstəricilər yer almışdır. Bu cür hesabat artıq üçüncü dəfə olaraq ictimaiyyət və futbol ailəsinin üzvləri üçün açıqlanır. Müəyyən göstəricilərin ictimaiyyətləşdirilməsinin ənənəvi hal Lisenziyalaşdırma prosesinin həyata keçirilməsi klub futbolu üçün ən vacib aldığını müsbət qiymətləndirərək, inanıram ki, bu cür hesabatlar klub futbolunun amillərdən biridir. Ötən mövsüm onu göstərdi ki, klublar bu prosesə daha da inkişafına öz töhfəsini verəcəkdir. məsuliyyətlə və diqqətlə yanaşmalıdır. Maliyyə çətinlikləri dövründə klublarda düzgün idarəetmə və peşəkar yanaşma çox vacibdir. Lisenziyalaşdırma sisteminin əsas məqsədlərindən biri də, məhz bu cür peşəkar yanaşmanın Rövnəq Abdullayev stimullaşdırılmasıdır. AFFA-nın prezidenti BİZ BİRLİKDƏ GÜCLÜYÜK! 3 Mündəricat Maraqlı faktlar 5 Lisenziyalaşdırma üzrə statistik göstəricilər 7 2015-16-cı il lisenziyalaşdırma mövsümündə qaydalarda dəyişikliklər 11 Mövsüm ərzində keçirilmiş