Chemistry of Catalytic Processes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9440/solvent-effects-on-structure-and-reaction-mechanism-a-theoretical-study-of-2-2-polar-cycloaddition-between-ketene-and-imine-159440.webp)

Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine

J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 7877-7881 7877 Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: A Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition between Ketene and Imine Thanh N. Truong Henry Eyring Center for Theoretical Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, UniVersity of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 ReceiVed: March 25, 1998; In Final Form: July 17, 1998 The effects of aqueous solvent on structures and mechanism of the [2 + 2] cycloaddition between ketene and imine were investigated by using correlated MP2 and MP4 levels of ab initio molecular orbital theory in conjunction with the dielectric continuum Generalized Conductor-like Screening Model (GCOSMO) for solvation. We found that reactions in the gas phase and in aqueous solution have very different topology on the free energy surfaces but have similar characteristic motion along the reaction coordinate. First, it involves formation of a planar trans-conformation zwitterionic complex, then a rotation of the two moieties to form the cycloaddition product. Aqueous solvent significantly stabilizes the zwitterionic complex, consequently changing the topology of the free energy surface from a gas-phase single barrier (one-step) process to a double barrier (two-step) one with a stable intermediate. Electrostatic solvent-solute interaction was found to be the dominant factor in lowering the activation energy by 4.5 kcal/mol. The present calculated results are consistent with previous experimental data. Introduction Lim and Jorgensen have also carried out free energy perturbation (FEP) theory simulations with accurate force field that includes + [2 2] cycloaddition reactions are useful synthetic routes to solute polarization effects and found even much larger solvent - formation of four-membered rings. -

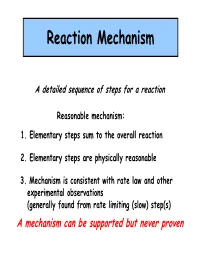

Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism A detailed sequence of steps for a reaction Reasonable mechanism: 1. Elementary steps sum to the overall reaction 2. Elementary steps are physically reasonable 3. Mechanism is consistent with rate law and other experimental observations (generally found from rate limiting (slow) step(s) A mechanism can be supported but never proven NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! Note the NO3 intermediate product! Arrhenius Equation Temperature dependence of k kAe E/RTa A = pre-exponential factor Ea= activation energy Now let’s look at the NO2 + CO reaction pathway* (1D). Just what IS a reaction coordinate? NO2 + CO NO + CO2 High barrier TS for step 1 Reactants: Lower barrier TS for step 2 NO2 +NO2 +CO Products Products Bottleneck NO +CO2 NO +CO2 Potential Energy Step 1 Step 2 Reaction Coordinate NO2 + CO NO + CO2 NO22 NO NO 3 NO NO CO NO CO 222In this two-step reaction, there are two barriers, one for each elementary step. The well between the two transition states holds a reactive intermediate. -

Chapter 14 Chemical Kinetics

Chapter 14 Chemical Kinetics Learning goals and key skills: Understand the factors that affect the rate of chemical reactions Determine the rate of reaction given time and concentration Relate the rate of formation of products and the rate of disappearance of reactants given the balanced chemical equation for the reaction. Understand the form and meaning of a rate law including the ideas of reaction order and rate constant. Determine the rate law and rate constant for a reaction from a series of experiments given the measured rates for various concentrations of reactants. Use the integrated form of a rate law to determine the concentration of a reactant at a given time. Explain how the activation energy affects a rate and be able to use the Arrhenius Equation. Predict a rate law for a reaction having multistep mechanism given the individual steps in the mechanism. Explain how a catalyst works. C (diamond) → C (graphite) DG°rxn = -2.84 kJ spontaneous! C (graphite) + O2 (g) → CO2 (g) DG°rxn = -394.4 kJ spontaneous! 1 Chemical kinetics is the study of how fast chemical reactions occur. Factors that affect rates of reactions: 1) physical state of the reactants. 2) concentration of the reactants. 3) temperature of the reaction. 4) presence or absence of a catalyst. 1) Physical State of the Reactants • The more readily the reactants collide, the more rapidly they react. – Homogeneous reactions are often faster. – Heterogeneous reactions that involve solids are faster if the surface area is increased; i.e., a fine powder reacts faster than a pellet. 2) Concentration • Increasing reactant concentration generally increases reaction rate since there are more molecules/vol., more collisions occur. -

Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions

Autumn 2004 Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions Why are kinetic analyses important? • Consider two classic examples in asymmetric catalysis: geraniol epoxidation 5-10% Ti(O-i-C3H7)4 O DET OH * * OH + TBHP CH2Cl2 3A mol sieve OH COOH5C2 L-(+)-DET = OH COOH5C2 * OH geraniol hydrogenation OH 0.1% Ru(II)-BINAP + H2 CH3OH P(C6H5)2 (S)-BINAP = P(C6 H5)2 • In both cases, high enantioselectivities may be achieved. However, there are fundamental differences between these two reactions which kinetics can inform us about. 1 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions geraniol epoxidation: • enantioselectivity is controlled primarily by the preferred mode of initial binding of the prochiral substrate and, therefore, the relative stability of intermediate species. The transition state resembles the intermediate species. Finn and Sharpless in Asymmetric Synthesis, Morrison, J.D., ed., Academic Press: New York, 1986, v. 5, p. 247. geraniol hydrogenation: • enantioselectivity may be dictated by the relative reactivity rather than the stability of the intermediate species. The transition state may not resemble the intermediate species. for example, hydrogenation of enamides using Rh+(dipamp) studied by Landis and Halpern (JACS, 1987, 109,1746) 2 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions “Asymmetric catalysis is four-dimensional chemistry. Simple stereochemical scrutiny of the substrate or reagent is not enough. The high efficiency that these reactions provide can only be achieved through a combination of both an ideal three-dimensional structure (x,y,z) and suitable kinetics (t).” R. Noyori, Asymmetric Catalysis in Organic Synthesis,Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1994, p.3. “Studying the photograph of a racehorse cannot tell you how fast it can run.” J. -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

Ketenes 25/01/2014 Part 1

Baran Group Meeting Hai Dao Ketenes 25/01/2014 Part 1. Introduction Ph Ph n H Pr3N C A brief history Cl C Ph + nPr NHCl Ph O 3 1828: Synthesis of urea = the starting point of modern organic chemistry. O 1901: Wedekind's proposal for the formation of ketene equivalent (confirmed by Staudinger 1911) Wedekind's proposal (1901) 1902: Wolff rearrangement, Wolff, L. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1902, 325, 129. 2 Wolff adopt a ketene structure in 1912. R 2 hν R R2 1905: First synthesis and characterization of a ketene: in an efford to synthesize radical 2, 1 ROH R C Staudinger has synthesized diphenylketene 3, Staudinger, H. et al., Chem. Ber. 1905, 1735. N2 1 RO CH or Δ C R C R1 1907-8: synthesis and dicussion about structure of the parent ketene, Wilsmore, O O J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1907, 1938; Wilsmore and Stewart Chem. Ber. 1908, 1025; Staudinger and Wolff rearrangement (1902) O Klever Chem. Ber. 1908, 1516. Ph Ph Cl Zn Ph O hot Pt wire Zn Br Cl Cl CH CH2 Ph C C vs. C Br C Ph Ph HO O O O O O O O 1 3 (isolated) 2 Wilsmore's synthesis and proposal (1907-8) Staudinger's synthesis and proposal (1908) wanted to make Staudinger's discovery (1905) Latest books: ketene (Tidwell, 1995), ketene II (Tidwell, 2006), Science of Synthesis, Vol. 23 (2006); Latest review: new direactions in ketene chemistry: the land of opportunity (Tidwell et al., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1081). Search for ketenes, Google gave 406,000 (vs. -

Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Reactions

8 NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION AND ELIMINATION REACTIONS substitution reactions involve the replacement of one atom or group (X) by another (Y): We already have described one very important type of substitution reaction, the halogenation of alkanes (Section 4-4), in which a hydrogen atom is re- placed by a halogen atom (X = H, Y = halogen). The chlorination of 2,2- dimethylpropane is an example: CH3 CH3 I I CH3-C-CH3 + C12 light > CH3-C-CH2Cl + HCI I I Reactions of this type proceed by radical-chain mechanisms in which the bonds are broken and formed by atoms or radicals as reactive intermediates. This 8-1 Classification of Reagents as Electrophiles and Nucleophiles. Acids and Bases mode of bond-breaking, in which one electron goes with R and the other with X, is called homolytic bond cleavage: R 'i: X + Y. - X . + R : Y a homolytic substitution reaction There are a large number of reactions, usually occurring in solution, that do not involve atoms or radicals but rather involve ions. They occur by heterolytic cleavage as opposed to homolytic cleavage of el~ctron-pairbonds. In heterolytic bond cleavage, the electron pair can be considered to go with one or the other of the groups R and X when the bond is broken. As one ex- ample, Y is a group such that it has an unshared electron pair and also is a negative ion. A heterolytic substitution reaction in which the R:X bonding pair goes with X would lead to RY and :X? R~:X+ :YO --' :x@+ R :Y a heterolytic substitution reaction A specific substitution reaction of this type is that of chloromethane with hydroxide ion to form methanol: In this chapter, we shall discuss substitution reactions that proceed by ionic or polar mechanisms' in which the bonds cleave heterolytically. -

The Mechanism of the Cycloaddition Reaction of 1,3-Dipole Molecules with Acetylene: an Investigation with the Unified Reaction Valley Approach

Theor Chem Acc (2014) 133:1423 DOI 10.1007/s00214-013-1423-z REGULAR ARTICLE The mechanism of the cycloaddition reaction of 1,3-dipole molecules with acetylene: an investigation with the unified reaction valley approach Marek Freindorf • Thomas Sexton • Elfi Kraka • Dieter Cremer Received: 10 September 2013 / Accepted: 12 November 2013 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2013 Abstract The unified reaction valley approach (URVA) between vibrational modes lead to an unusual energy is used in connection with a dual-level approach to describe exchange between just those bending modes that facilitate the mechanism of ten different cycloadditions of 1,3- the formation of radicaloid centers. The relative magnitude dipoles XYZ (diazonium betaines, nitrilium betaines, azo- of the reaction barriers and reaction energies is rationalized methines, and nitryl hydride) to acetylene utilizing density by determining reactant properties, which are responsible functional theory for the URVA calculations and for the mutual polarization of the reactants and the stability CCSD(T)-F12/aug-cc-pVTZ for the determination of the of the bonds to be broken or formed. reaction energetics. The URVA results reveal that the mechanism of the 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions is determined Keywords Unified reaction valley approach Á early in the van der Waals range where the mutual orien- 1,3-Dipolar cycloadditions Reaction mechanism tation of the reactants (resulting from the shape of the Mutual polarization EnergyÁ transfer and dissipationÁ Á enveloping exchange repulsion spheres, electrostatic attraction, and dispersion forces) decides on charge trans- fer, charge polarization, the formation of radicaloid cen- 1 Introduction ters, and the asynchronicity of bond formation. -

CHEMICAL KINETICS Pt 2 Reaction Mechanisms Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism (continued) CHEMICAL The reaction KINETICS 2 C H O +→5O + 6CO 4H O Pt 2 3 4 3 2 2 2 • has many steps in the reaction mechanism. Objectives ! Be able to describe the collision and Reaction Mechanisms transition-state theories • Even though a balanced chemical equation ! Be able to use the Arrhenius theory to may give the ultimate result of a reaction, determine the activation energy for a reaction and to predict rate constants what actually happens in the reaction may take place in several steps. ! Be able to relate the molecularity of the reaction and the reaction rate and • This “pathway” the reaction takes is referred to describle the concept of the “rate- as the reaction mechanism. determining” step • The individual steps in the larger overall reaction are referred to as elementary ! Be able to describe the role of a catalyst and homogeneous, heterogeneous and reactions. enzyme catalysis Reaction Mechanisms Often Used Terms •Intermediate: formed in one step and used up in a subsequent step and so is never seen as a product. The series of steps by which a chemical reaction occurs. •Molecularity: the number of species that must collide to produce the reaction indicated by that A chemical equation does not tell us how step. reactants become products - it is a summary of the overall process. •Elementary Step: A reaction whose rate law can be written from its molecularity. •uni, bi and termolecular 1 Elementary Reactions Elementary Reactions • Consider the reaction of nitrogen dioxide with • Each step is a singular molecular event carbon monoxide. -

Chemical Kinetics Reaction Mechanisms

Chemical Kinetics Kinetics is a study of the rate at which a chemical reaction occurs. The study of kinetics may be done in steps: Determination of reaction mechanism Prediction of rate law Measurement of reaction rates Comparison of predicted and measured rates Reaction Mechanisms Up to now, we have written chemical reactions as “net” reactions—a balanced chemical equation that shows the initial reactants and final products. A “reaction mechanism” shows the “elementary” reactions that must occur to produce the net reaction. An “elementary” reaction is a chemical reaction that actually takes place. 1 Reaction Mechanisms Every September since the early 80s, an “ozone hole” has developed over Antarctica which lasts until mid-November. O3 concentration-Dobson units 2 Reaction Mechanisms Average Ozone Concentrations for October over Halley's Bay 350 300 250 200 150 100 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Year Reaction Mechanisms The net reaction for this process is: 2 O3(g) 3 O2(g) If this reaction were an elementary reaction, then two ozone molecules would need to collide with each other in such a way to form a new O-O bond while breaking two other O-O bonds to form products: O O O 3 O2 O O O 3 Reaction Mechanisms It is hard to imagine this process happening based on our current understanding of chemical principles. The net reaction must proceed via some other set of elementary reactions: Reaction Mechanisms One possibility is: Cl + O3 ClO + O2 ClO + ClO ClOOCl ClOOCl Cl + ClOO ClOO Cl + O2 Cl + O3 ClO + O2 net: 2 O3 3 O2 4 Reaction Mechanisms In this mechanism, each elementary reaction makes sense chemically: Cl O O Cl-O + O-O O The chlorine atom abstracts an oxygen atom from ozone leaving ClO and molecular oxygen. -

Elimination Reactions Are Described

Introduction In this module, different types of elimination reactions are described. From a practical standpoint, elimination reactions widely used for the generation of double and triple bonds in compounds from a saturated precursor molecule. The presence of a good leaving group is a prerequisite in most elimination reactions. Traditional classification of elimination reactions, in terms of the molecularity of the reaction is employed. How the changes in the nature of the substrate as well as reaction conditions affect the mechanism of elimination are subsequently discussed. The stereochemical requirements for elimination in a given substrate and its consequence in the product stereochemistry is emphasized. ELIMINATION REACTIONS Objective and Outline beta-eliminations E1, E2 and E1cB mechanisms Stereochemical considerations of these reactions Examples of E1, E2 and E1cB reactions Alpha eliminations and generation of carbene I. Basics Elimination reactions involve the loss of fragments or groups from a molecule to generate multiple bonds. A generalized equation is shown below for 1,2-elimination wherein the X and Y from two adjacent carbon atoms are removed, elimination C C C C -XY X Y Three major types of elimination reactions are: α-elimination: two atoms or groups are removed from the same atom. It is also known as 1,1-elimination. H R R C X C + HX R Both H and X are removed from carbon atom here R Carbene β-elimination: loss of atoms or groups on adjacent atoms. It is also H H known as 1,2- elimination. R C C R R HC CH R X H γ-elimination: loss of atoms or groups from the 1st and 3rd positions as shown below. -

Chemical Kinetics Reaction Mechanisms

Chemical Kinetics π Kinetics is a study of the rate at which a chemical reaction occurs. π The study of kinetics may be done in steps: Determination of reaction mechanism Prediction of rate law Measurement of reaction rates Comparison of predicted and measured rates Reaction Mechanisms π Up to now, we have written chemical reactions as “net” reactions—a balanced chemical equation that shows the initial reactants and final products. π A “reaction mechanism” shows the “elementary” reactions that must occur to produce the net reaction. π An “elementary” reaction is a chemical reaction that actually takes place. 1 Reaction Mechanisms π Every September since the early 80s, an “ozone hole” has developed over Antarctica which lasts until mid-November. O3 concentration-Dobson units Reaction Mechanisms Average Ozone C oncentrati ons for October over H al l ey's B ay 350 300 250 200 150 100 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Year 2 Reaction Mechanisms π The net reaction for this process is: → 2 O3(g) 3 O2(g) π If this reaction were an elementary reaction, then two ozone molecules would need to collide with each other in such a way to form a new O-O bond while breaking two other O-O bonds to form products: O O O → 3 O2 O O O Reaction Mechanisms π It is hard to imagine this process happening based on our current understanding of chemical principles. π The net reaction must proceed via some other set of elementary reactions: 3 Reaction Mechanisms π One possibility is: → Cl + O3 ClO + O2 ClO + ClO → ClOOCl ClOOCl → Cl + ClOO → ClOO Cl + O2 → Cl + O3 ClO + O2 → net: 2 O3 3 O2 Reaction Mechanisms π In this mechanism, each elementary reaction makes sense chemically: Cl O O → Cl-O + O-O O π The chlorine atom abstracts an oxygen atom from ozone leaving ClO and molecular oxygen.