Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organic Chemistry

Wisebridge Learning Systems Organic Chemistry Reaction Mechanisms Pocket-Book WLS www.wisebridgelearning.com © 2006 J S Wetzel LEARNING STRATEGIES CONTENTS ● The key to building intuition is to develop the habit ALKANES of asking how each particular mechanism reflects Thermal Cracking - Pyrolysis . 1 general principles. Look for the concepts behind Combustion . 1 the chemistry to make organic chemistry more co- Free Radical Halogenation. 2 herent and rewarding. ALKENES Electrophilic Addition of HX to Alkenes . 3 ● Acid Catalyzed Hydration of Alkenes . 4 Exothermic reactions tend to follow pathways Electrophilic Addition of Halogens to Alkenes . 5 where like charges can separate or where un- Halohydrin Formation . 6 like charges can come together. When reading Free Radical Addition of HX to Alkenes . 7 organic chemistry mechanisms, keep the elec- Catalytic Hydrogenation of Alkenes. 8 tronegativities of the elements and their valence Oxidation of Alkenes to Vicinal Diols. 9 electron configurations always in your mind. Try Oxidative Cleavage of Alkenes . 10 to nterpret electron movement in terms of energy Ozonolysis of Alkenes . 10 Allylic Halogenation . 11 to make the reactions easier to understand and Oxymercuration-Demercuration . 13 remember. Hydroboration of Alkenes . 14 ALKYNES ● For MCAT preparation, pay special attention to Electrophilic Addition of HX to Alkynes . 15 Hydration of Alkynes. 15 reactions where the product hinges on regio- Free Radical Addition of HX to Alkynes . 16 and stereo-selectivity and reactions involving Electrophilic Halogenation of Alkynes. 16 resonant intermediates, which are special favor- Hydroboration of Alkynes . 17 ites of the test-writers. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Alkynes. 17 Reduction of Alkynes with Alkali Metal/Ammonia . 18 Formation and Use of Acetylide Anion Nucleophiles . -

Solvents and Solvent E¤Ects in Organic Chemistry

Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................... 1 2 Solute-Solvent Interactions ........................................... 7 2.1 Solutions . .......................................................... 7 2.2 Intermolecular Forces . ............................................ 12 2.2.1 Ion-Dipole Forces . ................................................. 13 2.2.2 Dipole-Dipole Forces................................................ 14 2.2.3 Dipole-Induced Dipole Forces ....................................... 15 2.2.4 Instantaneous Dipole-Induced Dipole Forces . ...................... 16 2.2.5 Hydrogen Bonding . ................................................. 17 2.2.6 Electron-Pair Donor/Electron-Pair Acceptor Interactions (EPD/EPA Interactions) . ..................................................... 23 2.2.7 Solvophobic Interactions ............................................ 31 2.3 Solvation . .......................................................... 34 2.4 Preferential Solvation................................................ 43 2.5 Micellar Solvation (Solubilization) ................................... 48 2.6 Ionization and Dissociation . ........................................ 52 3 Classification of Solvents ............................................. 65 3.1 Classification of Solvents according to Chemical Constitution ......... 65 3.2 Classification of Solvents using Physical Constants . .................. 75 3.3 Classification of Solvents in Terms of Acid-Base Behaviour. ......... 88 3.3.1 Brønsted-Lowry -

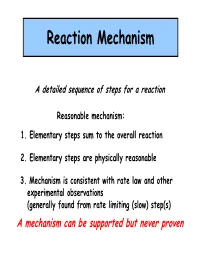

Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism A detailed sequence of steps for a reaction Reasonable mechanism: 1. Elementary steps sum to the overall reaction 2. Elementary steps are physically reasonable 3. Mechanism is consistent with rate law and other experimental observations (generally found from rate limiting (slow) step(s) A mechanism can be supported but never proven NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! Note the NO3 intermediate product! Arrhenius Equation Temperature dependence of k kAe E/RTa A = pre-exponential factor Ea= activation energy Now let’s look at the NO2 + CO reaction pathway* (1D). Just what IS a reaction coordinate? NO2 + CO NO + CO2 High barrier TS for step 1 Reactants: Lower barrier TS for step 2 NO2 +NO2 +CO Products Products Bottleneck NO +CO2 NO +CO2 Potential Energy Step 1 Step 2 Reaction Coordinate NO2 + CO NO + CO2 NO22 NO NO 3 NO NO CO NO CO 222In this two-step reaction, there are two barriers, one for each elementary step. The well between the two transition states holds a reactive intermediate. -

Chapter 14 Chemical Kinetics

Chapter 14 Chemical Kinetics Learning goals and key skills: Understand the factors that affect the rate of chemical reactions Determine the rate of reaction given time and concentration Relate the rate of formation of products and the rate of disappearance of reactants given the balanced chemical equation for the reaction. Understand the form and meaning of a rate law including the ideas of reaction order and rate constant. Determine the rate law and rate constant for a reaction from a series of experiments given the measured rates for various concentrations of reactants. Use the integrated form of a rate law to determine the concentration of a reactant at a given time. Explain how the activation energy affects a rate and be able to use the Arrhenius Equation. Predict a rate law for a reaction having multistep mechanism given the individual steps in the mechanism. Explain how a catalyst works. C (diamond) → C (graphite) DG°rxn = -2.84 kJ spontaneous! C (graphite) + O2 (g) → CO2 (g) DG°rxn = -394.4 kJ spontaneous! 1 Chemical kinetics is the study of how fast chemical reactions occur. Factors that affect rates of reactions: 1) physical state of the reactants. 2) concentration of the reactants. 3) temperature of the reaction. 4) presence or absence of a catalyst. 1) Physical State of the Reactants • The more readily the reactants collide, the more rapidly they react. – Homogeneous reactions are often faster. – Heterogeneous reactions that involve solids are faster if the surface area is increased; i.e., a fine powder reacts faster than a pellet. 2) Concentration • Increasing reactant concentration generally increases reaction rate since there are more molecules/vol., more collisions occur. -

Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions

Autumn 2004 Reaction Kinetics in Organic Reactions Why are kinetic analyses important? • Consider two classic examples in asymmetric catalysis: geraniol epoxidation 5-10% Ti(O-i-C3H7)4 O DET OH * * OH + TBHP CH2Cl2 3A mol sieve OH COOH5C2 L-(+)-DET = OH COOH5C2 * OH geraniol hydrogenation OH 0.1% Ru(II)-BINAP + H2 CH3OH P(C6H5)2 (S)-BINAP = P(C6 H5)2 • In both cases, high enantioselectivities may be achieved. However, there are fundamental differences between these two reactions which kinetics can inform us about. 1 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions geraniol epoxidation: • enantioselectivity is controlled primarily by the preferred mode of initial binding of the prochiral substrate and, therefore, the relative stability of intermediate species. The transition state resembles the intermediate species. Finn and Sharpless in Asymmetric Synthesis, Morrison, J.D., ed., Academic Press: New York, 1986, v. 5, p. 247. geraniol hydrogenation: • enantioselectivity may be dictated by the relative reactivity rather than the stability of the intermediate species. The transition state may not resemble the intermediate species. for example, hydrogenation of enamides using Rh+(dipamp) studied by Landis and Halpern (JACS, 1987, 109,1746) 2 Autumn 2004 Kinetics of Asymmetric Catalytic Reactions “Asymmetric catalysis is four-dimensional chemistry. Simple stereochemical scrutiny of the substrate or reagent is not enough. The high efficiency that these reactions provide can only be achieved through a combination of both an ideal three-dimensional structure (x,y,z) and suitable kinetics (t).” R. Noyori, Asymmetric Catalysis in Organic Synthesis,Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1994, p.3. “Studying the photograph of a racehorse cannot tell you how fast it can run.” J. -

The Arene–Alkene Photocycloaddition

The arene–alkene photocycloaddition Ursula Streit and Christian G. Bochet* Review Open Access Address: Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7, 525–542. Department of Chemistry, University of Fribourg, Chemin du Musée 9, doi:10.3762/bjoc.7.61 CH-1700 Fribourg, Switzerland Received: 07 January 2011 Email: Accepted: 23 March 2011 Ursula Streit - [email protected]; Christian G. Bochet* - Published: 28 April 2011 [email protected] This article is part of the Thematic Series "Photocycloadditions and * Corresponding author photorearrangements". Keywords: Guest Editor: A. G. Griesbeck benzene derivatives; cycloadditions; Diels–Alder; photochemistry © 2011 Streit and Bochet; licensee Beilstein-Institut. License and terms: see end of document. Abstract In the presence of an alkene, three different modes of photocycloaddition with benzene derivatives can occur; the [2 + 2] or ortho, the [3 + 2] or meta, and the [4 + 2] or para photocycloaddition. This short review aims to demonstrate the synthetic power of these photocycloadditions. Introduction Photocycloadditions occur in a variety of modes [1]. The best In the presence of an alkene, three different modes of photo- known representatives are undoubtedly the [2 + 2] photocyclo- cycloaddition with benzene derivatives can occur, viz. the addition, forming either cyclobutanes or four-membered hetero- [2 + 2] or ortho, the [3 + 2] or meta, and the [4 + 2] or para cycles (as in the Paternò–Büchi reaction), whilst excited-state photocycloaddition (Scheme 2). The descriptors ortho, meta [4 + 4] cycloadditions can also occur to afford cyclooctadiene and para only indicate the connectivity to the aromatic ring, and compounds. On the other hand, the well-known thermal [4 + 2] do not have any implication with regard to the reaction mecha- cycloaddition (Diels–Alder reaction) is only very rarely nism. -

Diastereoisomers As Probes for Solvent Reorganizational Effects On

Chemical Physics 324 (2006) 8–25 www.elsevier.com/locate/chemphys Diastereoisomers as probes for solvent reorganizational effects on IVCT in dinuclear ruthenium complexes Deanna M. DÕAlessandro, F. Richard Keene * Department of Chemistry, School of Pharmacy and Molecular Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Qld. 4811, Australia Received 19 June 2005; accepted 1 September 2005 Available online 3 October 2005 Abstract 5+ 0 0 IVCT solvatochromism studies on the meso and rac diastereoisomers of [{Ru(bpy)2}2(l-bpm)] (bpy = 2,2 -bipyridine; bpm = 2,2 - bipyrimidine) in a homologous series of nitrile solvents revealed that stereochemically directed specific solvent effects in the first solvation shell dominated the outer sphere contribution to the reorganizational energy for intramolecular electron transfer. Further, solvent pro- portion experiments in acetonitrile/propionitrile mixtures indicated that the magnitude and direction of the specific effect was dependent on the relative abilities of discrete solvent molecules to penetrate the clefts between the planes of the terminal polypyridyl ligands. In particular, the specific effects were dependent on the dimensionality of the clefts, and the number, size, orientation and location of the solvent dipoles within the interior and exterior clefts. 5+ 5+ IVCT solvatochromism studies on the diastereoisomeric forms of [{Ru(bpy)2}2(l-dbneil)] and [{Ru(pp)2}2(l-bpm)] {dbneil = dibenzoeilatin; pp = substituted derivatives of 2,20-bipyridine and 1,10-phenanthroline} revealed that the subtle and systematic changes in the nature of the clefts by the variation of the bridging ligand, and the judicious positioning of substituents on the terminal ligands, profoundly influenced the magnitude of the reorganizational energy contribution to the electron transfer barrier. -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

Ketenes 25/01/2014 Part 1

Baran Group Meeting Hai Dao Ketenes 25/01/2014 Part 1. Introduction Ph Ph n H Pr3N C A brief history Cl C Ph + nPr NHCl Ph O 3 1828: Synthesis of urea = the starting point of modern organic chemistry. O 1901: Wedekind's proposal for the formation of ketene equivalent (confirmed by Staudinger 1911) Wedekind's proposal (1901) 1902: Wolff rearrangement, Wolff, L. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1902, 325, 129. 2 Wolff adopt a ketene structure in 1912. R 2 hν R R2 1905: First synthesis and characterization of a ketene: in an efford to synthesize radical 2, 1 ROH R C Staudinger has synthesized diphenylketene 3, Staudinger, H. et al., Chem. Ber. 1905, 1735. N2 1 RO CH or Δ C R C R1 1907-8: synthesis and dicussion about structure of the parent ketene, Wilsmore, O O J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1907, 1938; Wilsmore and Stewart Chem. Ber. 1908, 1025; Staudinger and Wolff rearrangement (1902) O Klever Chem. Ber. 1908, 1516. Ph Ph Cl Zn Ph O hot Pt wire Zn Br Cl Cl CH CH2 Ph C C vs. C Br C Ph Ph HO O O O O O O O 1 3 (isolated) 2 Wilsmore's synthesis and proposal (1907-8) Staudinger's synthesis and proposal (1908) wanted to make Staudinger's discovery (1905) Latest books: ketene (Tidwell, 1995), ketene II (Tidwell, 2006), Science of Synthesis, Vol. 23 (2006); Latest review: new direactions in ketene chemistry: the land of opportunity (Tidwell et al., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 1081). Search for ketenes, Google gave 406,000 (vs. -

S.T.E.T.Women's College, Mannargudi Semester Iii Ii M

S.T.E.T.WOMEN’S COLLEGE, MANNARGUDI SEMESTER III II M.Sc., CHEMISTRY ORGANIC CHEMISTRY - II – P16CH31 UNIT I Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution – mechanisms – SN1, SN2, SNi – ion-pair in SN1 mechanisms – neighbouring group participation, non-classical carbocations – substitutions at allylic and vinylic carbons. Reactivity – effect of structure, nucleophile, leaving group and stereochemical factors – correlation of structure with reactivity – solvent effects – rearrangements involving carbocations – Wagner-Meerwein and dienone-phenol rearrangements. Aromatic nucleophilic substitutions – SN1, SNAr, Benzyne mechanism – reactivity orientation – Ullmann, Sandmeyer and Chichibabin reaction – rearrangements involving nucleophilic substitution – Stevens – Sommelet Hauser and von-Richter rearrangements. NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION Mechanism of Aliphatic Nucleophilic Substitution. Aliphatic nucleophilic substitution clearly involves the donation of a lone pair from the nucleophile to the tetrahedral, electrophilic carbon bonded to a halogen. For that reason, it attracts to nucleophile In organic chemistry and inorganic chemistry, nucleophilic substitution is a fundamental class of reactions in which a leaving group(nucleophile) is replaced by an electron rich compound(nucleophile). The whole molecular entity of which the electrophile and the leaving group are part is usually called the substrate. The nucleophile essentially attempts to replace the leaving group as the primary substituent in the reaction itself, as a part of another molecule. The most general form of the reaction may be given as the following: Nuc: + R-LG → R-Nuc + LG: The electron pair (:) from the nucleophile(Nuc) attacks the substrate (R-LG) forming a new 1 bond, while the leaving group (LG) departs with an electron pair. The principal product in this case is R-Nuc. The nucleophile may be electrically neutral or negatively charged, whereas the substrate is typically neutral or positively charged. -

Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition

Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition Reactions Marta Glavatskikh, Timur Madzhidov, Dragos Horvath, Ramil Nugmanov, Timur Gimadiev, Daria Malakhova, Gilles Marcou, Alexandre Varnek To cite this version: Marta Glavatskikh, Timur Madzhidov, Dragos Horvath, Ramil Nugmanov, Timur Gimadiev, et al.. Predictive Models for Kinetic Parameters of Cycloaddition Reactions. Molecular Informatics, Wiley- VCH, 2018, 38 (1-2), pp.1800077. 10.1002/minf.201800077. hal-02346844 HAL Id: hal-02346844 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02346844 Submitted on 5 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 0DQXVFULSW &OLFNKHUHWRGRZQORDG0DQXVFULSW&$UHYLVLRQGRF[ Predictive models for kinetic parameters of cycloaddition reactions Marta Glavatskikh[a,b], Timur Madzhidov[b], Dragos Horvath[a], Ramil Nugmanov[b], Timur Gimadiev[a,b], Daria Malakhova[b], Gilles Marcou[a] and Alexandre Varnek*[a] [a] Laboratoire de Chémoinformatique, UMR 7140 CNRS, Université de Strasbourg, 1, rue Blaise Pascal, 67000 Strasbourg, France; [b] Laboratory of Chemoinformatics and Molecular Modeling, Butlerov Institute of Chemistry, Kazan Federal University, Kremlyovskaya str. 18, Kazan, Russia Abstract This paper reports SVR (Support Vector Regression) and GTM (Generative Topographic Mapping) modeling of three kinetic properties of cycloaddition reactions: rate constant (logk), activation energy (Ea) and pre-exponential factor (logA). -

Nucleophilic Substitution and Elimination Reactions

8 NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION AND ELIMINATION REACTIONS substitution reactions involve the replacement of one atom or group (X) by another (Y): We already have described one very important type of substitution reaction, the halogenation of alkanes (Section 4-4), in which a hydrogen atom is re- placed by a halogen atom (X = H, Y = halogen). The chlorination of 2,2- dimethylpropane is an example: CH3 CH3 I I CH3-C-CH3 + C12 light > CH3-C-CH2Cl + HCI I I Reactions of this type proceed by radical-chain mechanisms in which the bonds are broken and formed by atoms or radicals as reactive intermediates. This 8-1 Classification of Reagents as Electrophiles and Nucleophiles. Acids and Bases mode of bond-breaking, in which one electron goes with R and the other with X, is called homolytic bond cleavage: R 'i: X + Y. - X . + R : Y a homolytic substitution reaction There are a large number of reactions, usually occurring in solution, that do not involve atoms or radicals but rather involve ions. They occur by heterolytic cleavage as opposed to homolytic cleavage of el~ctron-pairbonds. In heterolytic bond cleavage, the electron pair can be considered to go with one or the other of the groups R and X when the bond is broken. As one ex- ample, Y is a group such that it has an unshared electron pair and also is a negative ion. A heterolytic substitution reaction in which the R:X bonding pair goes with X would lead to RY and :X? R~:X+ :YO --' :x@+ R :Y a heterolytic substitution reaction A specific substitution reaction of this type is that of chloromethane with hydroxide ion to form methanol: In this chapter, we shall discuss substitution reactions that proceed by ionic or polar mechanisms' in which the bonds cleave heterolytically.