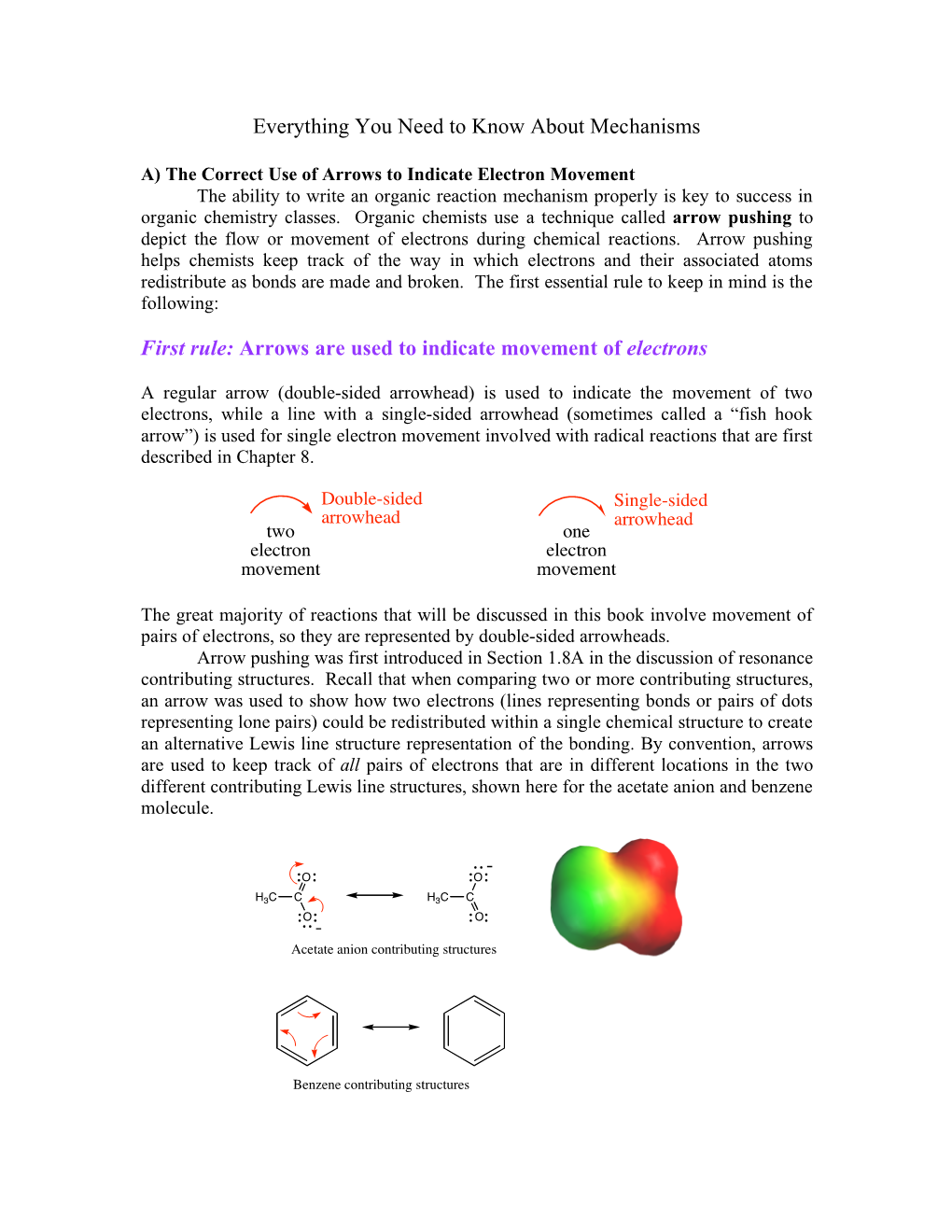

Everything You Need to Know About Mechanisms First Rule: Arrows Are

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemistry Grade Level 10 Units 1-15

COPPELL ISD SUBJECT YEAR AT A GLANCE GRADE HEMISTRY UNITS C LEVEL 1-15 10 Program Transfer Goals ● Ask questions, recognize and define problems, and propose solutions. ● Safely and ethically collect, analyze, and evaluate appropriate data. ● Utilize, create, and analyze models to understand the world. ● Make valid claims and informed decisions based on scientific evidence. ● Effectively communicate scientific reasoning to a target audience. PACING 1st 9 Weeks 2nd 9 Weeks 3rd 9 Weeks 4th 9 Weeks Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Unit 6 Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1.5 wks 2 wks 1.5 wks 2 wks 3 wks 5.5 wks 1.5 2 2.5 2 wks 2 2 2 wks 1.5 1.5 wks wks wks wks wks wks wks Assurances for a Guaranteed and Viable Curriculum Adherence to this scope and sequence affords every member of the learning community clarity on the knowledge and skills on which each learner should demonstrate proficiency. In order to deliver a guaranteed and viable curriculum, our team commits to and ensures the following understandings: Shared Accountability: Responding -

Prebiological Evolution and the Metabolic Origins of Life

Prebiological Evolution and the Andrew J. Pratt* Metabolic Origins of Life University of Canterbury Keywords Abiogenesis, origin of life, metabolism, hydrothermal, iron Abstract The chemoton model of cells posits three subsystems: metabolism, compartmentalization, and information. A specific model for the prebiological evolution of a reproducing system with rudimentary versions of these three interdependent subsystems is presented. This is based on the initial emergence and reproduction of autocatalytic networks in hydrothermal microcompartments containing iron sulfide. The driving force for life was catalysis of the dissipation of the intrinsic redox gradient of the planet. The codependence of life on iron and phosphate provides chemical constraints on the ordering of prebiological evolution. The initial protometabolism was based on positive feedback loops associated with in situ carbon fixation in which the initial protometabolites modified the catalytic capacity and mobility of metal-based catalysts, especially iron-sulfur centers. A number of selection mechanisms, including catalytic efficiency and specificity, hydrolytic stability, and selective solubilization, are proposed as key determinants for autocatalytic reproduction exploited in protometabolic evolution. This evolutionary process led from autocatalytic networks within preexisting compartments to discrete, reproducing, mobile vesicular protocells with the capacity to use soluble sugar phosphates and hence the opportunity to develop nucleic acids. Fidelity of information transfer in the reproduction of these increasingly complex autocatalytic networks is a key selection pressure in prebiological evolution that eventually leads to the selection of nucleic acids as a digital information subsystem and hence the emergence of fully functional chemotons capable of Darwinian evolution. 1 Introduction: Chemoton Subsystems and Evolutionary Pathways Living cells are autocatalytic entities that harness redox energy via the selective catalysis of biochemical transformations. -

The Practice of Chemistry Education (Paper)

CHEMISTRY EDUCATION: THE PRACTICE OF CHEMISTRY EDUCATION RESEARCH AND PRACTICE (PAPER) 2004, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 69-87 Concept teaching and learning/ History and philosophy of science (HPS) Juan QUÍLEZ IES José Ballester, Departamento de Física y Química, Valencia (Spain) A HISTORICAL APPROACH TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIUM THROUGH THE EVOLUTION OF THE AFFINITY CONCEPT: SOME EDUCATIONAL SUGGESTIONS Received 20 September 2003; revised 11 February 2004; in final form/accepted 20 February 2004 ABSTRACT: Three basic ideas should be considered when teaching and learning chemical equilibrium: incomplete reaction, reversibility and dynamics. In this study, we concentrate on how these three ideas have eventually defined the chemical equilibrium concept. To this end, we analyse the contexts of scientific inquiry that have allowed the growth of chemical equilibrium from the first ideas of chemical affinity. At the beginning of the 18th century, chemists began the construction of different affinity tables, based on the concept of elective affinities. Berthollet reworked this idea, considering that the amount of the substances involved in a reaction was a key factor accounting for the chemical forces. Guldberg and Waage attempted to measure those forces, formulating the first affinity mathematical equations. Finally, the first ideas providing a molecular interpretation of the macroscopic properties of equilibrium reactions were presented. The historical approach of the first key ideas may serve as a basis for an appropriate sequencing of -

![Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9440/solvent-effects-on-structure-and-reaction-mechanism-a-theoretical-study-of-2-2-polar-cycloaddition-between-ketene-and-imine-159440.webp)

Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine

J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 7877-7881 7877 Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: A Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition between Ketene and Imine Thanh N. Truong Henry Eyring Center for Theoretical Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, UniVersity of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 ReceiVed: March 25, 1998; In Final Form: July 17, 1998 The effects of aqueous solvent on structures and mechanism of the [2 + 2] cycloaddition between ketene and imine were investigated by using correlated MP2 and MP4 levels of ab initio molecular orbital theory in conjunction with the dielectric continuum Generalized Conductor-like Screening Model (GCOSMO) for solvation. We found that reactions in the gas phase and in aqueous solution have very different topology on the free energy surfaces but have similar characteristic motion along the reaction coordinate. First, it involves formation of a planar trans-conformation zwitterionic complex, then a rotation of the two moieties to form the cycloaddition product. Aqueous solvent significantly stabilizes the zwitterionic complex, consequently changing the topology of the free energy surface from a gas-phase single barrier (one-step) process to a double barrier (two-step) one with a stable intermediate. Electrostatic solvent-solute interaction was found to be the dominant factor in lowering the activation energy by 4.5 kcal/mol. The present calculated results are consistent with previous experimental data. Introduction Lim and Jorgensen have also carried out free energy perturbation (FEP) theory simulations with accurate force field that includes + [2 2] cycloaddition reactions are useful synthetic routes to solute polarization effects and found even much larger solvent - formation of four-membered rings. -

Andrea Deoudes, Kinetics: a Clock Reaction

A Kinetics Experiment The Rate of a Chemical Reaction: A Clock Reaction Andrea Deoudes February 2, 2010 Introduction: The rates of chemical reactions and the ability to control those rates are crucial aspects of life. Chemical kinetics is the study of the rates at which chemical reactions occur, the factors that affect the speed of reactions, and the mechanisms by which reactions proceed. The reaction rate depends on the reactants, the concentrations of the reactants, the temperature at which the reaction takes place, and any catalysts or inhibitors that affect the reaction. If a chemical reaction has a fast rate, a large portion of the molecules react to form products in a given time period. If a chemical reaction has a slow rate, a small portion of molecules react to form products in a given time period. This experiment studied the kinetics of a reaction between an iodide ion (I-1) and a -2 -1 -2 -2 peroxydisulfate ion (S2O8 ) in the first reaction: 2I + S2O8 I2 + 2SO4 . This is a relatively slow reaction. The reaction rate is dependent on the concentrations of the reactants, following -1 m -2 n the rate law: Rate = k[I ] [S2O8 ] . In order to study the kinetics of this reaction, or any reaction, there must be an experimental way to measure the concentration of at least one of the reactants or products as a function of time. -2 -2 -1 This was done in this experiment using a second reaction, 2S2O3 + I2 S4O6 + 2I , which occurred simultaneously with the reaction under investigation. Adding starch to the mixture -2 allowed the S2O3 of the second reaction to act as a built in “clock;” the mixture turned blue -2 -2 when all of the S2O3 had been consumed. -

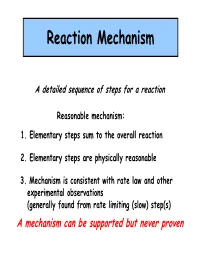

Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism A detailed sequence of steps for a reaction Reasonable mechanism: 1. Elementary steps sum to the overall reaction 2. Elementary steps are physically reasonable 3. Mechanism is consistent with rate law and other experimental observations (generally found from rate limiting (slow) step(s) A mechanism can be supported but never proven NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! Note the NO3 intermediate product! Arrhenius Equation Temperature dependence of k kAe E/RTa A = pre-exponential factor Ea= activation energy Now let’s look at the NO2 + CO reaction pathway* (1D). Just what IS a reaction coordinate? NO2 + CO NO + CO2 High barrier TS for step 1 Reactants: Lower barrier TS for step 2 NO2 +NO2 +CO Products Products Bottleneck NO +CO2 NO +CO2 Potential Energy Step 1 Step 2 Reaction Coordinate NO2 + CO NO + CO2 NO22 NO NO 3 NO NO CO NO CO 222In this two-step reaction, there are two barriers, one for each elementary step. The well between the two transition states holds a reactive intermediate. -

Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis

j1 Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis, Third Edition. Edited by Karlheinz Drauz, Harald Groger,€ and Oliver May. Ó 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Published 2012 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. j3 1 Introduction – Principles and Historical Landmarks of Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis Harald Gr€oger and Yasuhisa Asano 1.1 General Remarks Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis – behind this term stands a technology that today is widely recognized as a first choice opportunity in the preparation of a wide range of chemical compounds. Notably, this is true not only for academic syntheses but also for industrial-scale applications [1]. For numerous molecules the synthetic routes based on enzyme catalysis have turned out to be competitive (and often superior!) compared with classic chemicalaswellaschemocatalyticsynthetic approaches. Thus, enzymatic catalysis is increasingly recognized by organic chemists in both academia and industry as an attractive synthetic tool besides the traditional organic disciplines such as classic synthesis, metal catalysis, and organocatalysis [2]. By means of enzymes a broad range of transformations relevant in organic chemistry can be catalyzed, including, for example, redox reactions, carbon–carbon bond forming reactions, and hydrolytic reactions. Nonetheless, for a long time enzyme catalysis was not realized as a first choice option in organic synthesis. Organic chemists did not use enzymes as catalysts for their envisioned syntheses because of observed (or assumed) disadvantages such as narrow substrate range, limited stability of enzymes under organic reaction conditions, low efficiency when using wild-type strains, and diluted substrate and product solutions, thus leading to non-satisfactory volumetric productivities. -

Chapter 10 – Chemical Reactions Notes

Chapter 8 – Chemical Reactions Notes Chemical Reactions: Chemical reactions are processes in which the atoms of one or more substances are rearranged to form different chemical compounds. How to tell if a chemical reaction has occurred (recap): Temperature changes that can’t be accounted for. o Exothermic reactions give off energy (as in fire). o Endothermic reactions absorb energy (as in a cold pack). Spontaneous color change. o This happens when things rust, when they rot, and when they burn. Appearance of a solid when two liquids are mixed. o This solid is called a precipitate. Formation of a gas / bubbling, as when vinegar and baking soda are mixed. Overall, the most important thing to remember is that a chemical reaction produces a whole new chemical compound. Just changing the way that something looks (breaking, melting, dissolving, etc) isn’t enough to qualify something as a chemical reaction! Balancing Equations Notes: Things to keep in mind when looking at the recipes for chemical reactions: 1) The stuff before the arrow is referred to as the “reactants” or “reagents”, and the stuff after the arrow is called the “products.” 2) The number of atoms of each element is the same on both sides of the arrow. Even though there may be different numbers of molecules, the number of atoms of each element needs to remain the same to obey the law of conservation of mass. 3) The numbers in front of the formulas tell you how many molecules or moles of each chemical are involved in the reaction. 4) Equations are nothing more than chemical recipes. -

Recyclable Catalysts for Alkyne Functionalization

molecules Review Recyclable Catalysts for Alkyne Functionalization Leslie Trigoura 1,2 , Yalan Xing 1,* and Bhanu P. S. Chauhan 2,* 1 Department of Chemistry, William Paterson University of New Jersey, 300 Pompton Road, Wayne, NJ 07470, USA; [email protected] 2 Engineered Nanomaterials Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, William Paterson University of New Jersey, 300 Pompton Road, Wayne, NJ 07470, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.X.); [email protected] (B.P.S.C.); Tel.: +1-973-720-2470 (B.P.S.C.) Abstract: In this review, we present an assessment of recent advances in alkyne functionalization reactions, classified according to different classes of recyclable catalysts. In this work, we have in- corporated and reviewed the activity and selectivity of recyclable catalytic systems such as polysiloxane- encapsulated novel metal nanoparticle-based catalysts, silica–copper-supported nanocatalysts, graphitic carbon-supported nanocatalysts, metal organic framework (MOF) catalysts, porous organic frame- work (POP) catalysts, bio-material-supported catalysts, and metal/solvent free recyclable catalysts. In addition, several alkyne functionalization reactions have been elucidated to demonstrate the success and efficiency of recyclable catalysts. In addition, this review also provides the fundamental knowl- edge required for utilization of green catalysts, which can combine the advantageous features of both homogeneous (catalyst modulation) and heterogeneous (catalyst recycling) catalysis. Keywords: green catalysts; nanosystems; nanoscale catalysts; catalyst modulation; alkyne functional- ization; coupling reactions Citation: Trigoura, L.; Xing, Y.; 1. Introduction Chauhan, B.P.S. Recyclable Catalysts for Alkyne Functionalization. Alkyne functionalization methods constitute one of the most relevant topics in organic Molecules 2021, 26, 3525. https:// synthesis and has resulted in numerous advancements over several years. -

Often an Acidic Proton)

314 Arrow Pushing practice/Beauchamp 1 Electrophile = electron loving = any general electron pair acceptor = Lewis acid, (often an acidic proton) Nucleophile = nucleus/positive loving = any general electron pair donor = Lewis base, (often donated to an acidic proton) Problems - In the following reactions each step has been written without the formal charge or lone pairs of electrons and curved arrows. Assume each atom follows the normal octet rule, except hydrogen (duet rule). Supply the lone pairs, formal charge and the curved arrows to show how the electrons move for each step of the reaction mechanism. Identify any obvious nucleophiles and electrophiles in each of the steps of the reactions below (on the left side of each reaction arrow). A separate answer file will be created, as I get to it. Let me know when you find errors. RX reactions Examples of important patterns to know from our starting points (plus a few extras). methyl and primary secondary tertiary special H3C X very good very poor SN2 patterns SN2,E2,SN1,E1 X X X X X vinyl allylic X X X X X X X benzylic X phenyl X X There are many X variations. X 1o neopentyl 1. SN2 and SN2 a b I Br Br N C I I C I N 2. SN2 and E2 a b H Br H O HC C H I HC C Br OH I 3. SN2 and SN2 a Na b Na Na Br S HC C Br Br O O S Na Br R R Z:\classes\315\315 Handouts\arrow pushing mechs, probs.doc 314 Arrow Pushing practice/Beauchamp 2 4. -

Arrow Pushing: Mechanisms

Arrow Pushing: Mechanisms A few rules to follow: X H H 1) Arrows show the movement of ELECTRONS! HO HO They go from site of high electron density, usually a lone pair or alkene, to sites of low electron density, Correct OTs Incorrect OTs usually a cation, hydrogen, or unfilled orbital. H H H H 2) Balance the equation. Be sure to conserve mass and charge. If you start with an over charge of +1, +1 Incorrect 0 you need to end with an overall charge of +1. +1 Correct +1 Br Br CN Br CN Br H H 3) Draw out all intermediates. Include hydrogens, lone CN NC pairs, and charges. Be sure there are no carbons with X Incorrect H 5 bonds or other chemical errors in the intermediates. Correct 5 bonds to C OH Cl Cl HCl 4) The mechanism should give the observed product. + Do not forget about stereochemistry and regiochemistry. This mechanism HAS to go via a SN1 Let's try an example: HO cat. TsOH Given this reaction scheme we can determine that this will be an elimination type mechanism, specifically E1. CH HO CH3 2 The reaction scheme may not show all by products! CH CH3 cat. TsOH 3 + H2O Let's draw all hydrogens and balance the equation. H The lone pair on oxygen would be a site of high electron HO CH3 O CH3 O H O density and an acidic hydrogen (TsOH) is a site of low OH + OH CH3 H S CH3 S electron density. Note: TsOH is catalytic so it needs to O O O O be regenerated in our mechanism! H Now that we have made a charged species we want to CH H O CH3 3 find a way to stabalize or neutralize the charge. -

Organic Chemistry PEIMS Code: N1120027 Abbreviation: ORGCHEM Number of Credits That May Be Earned: 1/2-1

Course: Organic Chemistry PEIMS Code: N1120027 Abbreviation: ORGCHEM Number of credits that may be earned: 1/2-1 Brief description of the course (150 words or less): Organic chemistry is an introductory course that is designed for the student who intends to continue future study in the sciences. The student will learn the concepts and applications of organic chemistry. Topics covered include aliphatic and aromatic compounds, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, acids, ethers, amines, spectra, and stereochemistry. A brief introduction into biochemistry is also provided. The laboratory experiments will familiarize the student with the important laboratory techniques, specifically spectroscopy. Traditional high school chemistry courses focus on the inorganic aspects of chemistry whereas organic chemistry introduces the student to organic compounds and their properties, mechanisms of formations, and introduces the student to laboratory techniques beyond the traditional high school chemistry curriculum. Essential Knowledge and Skills of the course: (a) General requirements. This course is recommended for students in Grades 11-12. The recommended prerequisite for this course is AP Chemistry. (b) Introduction. Organic chemistry is designed to introduce students to the fundamental concepts of organic chemistry and key experimental evidence and data, which support these concepts. Students will learn to apply these data and concepts to chemical problem solving. Additionally, students will learn that organic chemistry is still evolving by reading about current breakthroughs in the field. Finally, students will gain appreciation for role that organic chemistry plays in modern technological developments in diverse fields, ranging from biology to materials science. (c) Knowledge and skills. (1) The student will be able to write both common an IUPAC names for the hydrocarbon.