The Kinetics and Mechanisms of Some Fundamental Organic Reactions of Nitro Compounds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chemistry Grade Level 10 Units 1-15

COPPELL ISD SUBJECT YEAR AT A GLANCE GRADE HEMISTRY UNITS C LEVEL 1-15 10 Program Transfer Goals ● Ask questions, recognize and define problems, and propose solutions. ● Safely and ethically collect, analyze, and evaluate appropriate data. ● Utilize, create, and analyze models to understand the world. ● Make valid claims and informed decisions based on scientific evidence. ● Effectively communicate scientific reasoning to a target audience. PACING 1st 9 Weeks 2nd 9 Weeks 3rd 9 Weeks 4th 9 Weeks Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Unit 4 Unit 5 Unit 6 Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit Unit 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 1.5 wks 2 wks 1.5 wks 2 wks 3 wks 5.5 wks 1.5 2 2.5 2 wks 2 2 2 wks 1.5 1.5 wks wks wks wks wks wks wks Assurances for a Guaranteed and Viable Curriculum Adherence to this scope and sequence affords every member of the learning community clarity on the knowledge and skills on which each learner should demonstrate proficiency. In order to deliver a guaranteed and viable curriculum, our team commits to and ensures the following understandings: Shared Accountability: Responding -

The Practice of Chemistry Education (Paper)

CHEMISTRY EDUCATION: THE PRACTICE OF CHEMISTRY EDUCATION RESEARCH AND PRACTICE (PAPER) 2004, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 69-87 Concept teaching and learning/ History and philosophy of science (HPS) Juan QUÍLEZ IES José Ballester, Departamento de Física y Química, Valencia (Spain) A HISTORICAL APPROACH TO THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHEMICAL EQUILIBRIUM THROUGH THE EVOLUTION OF THE AFFINITY CONCEPT: SOME EDUCATIONAL SUGGESTIONS Received 20 September 2003; revised 11 February 2004; in final form/accepted 20 February 2004 ABSTRACT: Three basic ideas should be considered when teaching and learning chemical equilibrium: incomplete reaction, reversibility and dynamics. In this study, we concentrate on how these three ideas have eventually defined the chemical equilibrium concept. To this end, we analyse the contexts of scientific inquiry that have allowed the growth of chemical equilibrium from the first ideas of chemical affinity. At the beginning of the 18th century, chemists began the construction of different affinity tables, based on the concept of elective affinities. Berthollet reworked this idea, considering that the amount of the substances involved in a reaction was a key factor accounting for the chemical forces. Guldberg and Waage attempted to measure those forces, formulating the first affinity mathematical equations. Finally, the first ideas providing a molecular interpretation of the macroscopic properties of equilibrium reactions were presented. The historical approach of the first key ideas may serve as a basis for an appropriate sequencing of -

Chapter 12 Lecture Notes

Chemical Kinetics “The study of speeds of reactions and the nanoscale pathways or rearrangements by which atoms and molecules are transformed to products” Chapter 13: Chemical Kinetics: Rates of Reactions © 2008 Brooks/Cole 1 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 2 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate Combustion of Fe(s) powder: © 2008 Brooks/Cole 3 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 4 Reaction Rate Reaction Rate + Change in [reactant] or [product] per unit time. Average rate of the Cv reaction can be calculated: Time, t [Cv+] Average rate + Cresol violet (Cv ; a dye) decomposes in NaOH(aq): (s) (mol / L) (mol L-1 s-1) 0.0 5.000 x 10-5 13.2 x 10-7 10.0 3.680 x 10-5 9.70 x 10-7 20.0 2.710 x 10-5 7.20 x 10-7 30.0 1.990 x 10-5 5.30 x 10-7 40.0 1.460 x 10-5 3.82 x 10-7 + - 50.0 1.078 x 10-5 Cv (aq) + OH (aq) → CvOH(aq) 2.85 x 10-7 60.0 0.793 x 10-5 -7 + + -5 1.82 x 10 change in concentration of Cv Δ [Cv ] 80.0 0.429 x 10 rate = = 0.99 x 10-7 elapsed time Δt 100.0 0.232 x 10-5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 5 © 2008 Brooks/Cole 6 1 Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Reaction Rates and Stoichiometry Cv+(aq) + OH-(aq) → CvOH(aq) For any general reaction: a A + b B c C + d D Stoichiometry: The overall rate of reaction is: Loss of 1 Cv+ → Gain of 1 CvOH Rate of Cv+ loss = Rate of CvOH gain 1 Δ[A] 1 Δ[B] 1 Δ[C] 1 Δ[D] Rate = − = − = + = + Another example: a Δt b Δt c Δt d Δt 2 N2O5(g) 4 NO2(g) + O2(g) Reactants decrease with time. -

Chapter 9. Atomic Transport Properties

NEA/NSC/R(2015)5 Chapter 9. Atomic transport properties M. Freyss CEA, DEN, DEC, Centre de Cadarache, France Abstract As presented in the first chapter of this book, atomic transport properties govern a large panel of nuclear fuel properties, from its microstructure after fabrication to its behaviour under irradiation: grain growth, oxidation, fission product release, gas bubble nucleation. The modelling of the atomic transport properties is therefore the key to understanding and predicting the material behaviour under irradiation or in storage conditions. In particular, it is noteworthy that many modelling techniques within the so-called multi-scale modelling scheme of materials make use of atomic transport data as input parameters: activation energies of diffusion, diffusion coefficients, diffusion mechanisms, all of which are then required to be known accurately. Modelling approaches that are readily used or which could be used to determine atomic transport properties of nuclear materials are reviewed here. They comprise, on the one hand, static atomistic calculations, in which the migration mechanism is fixed and the corresponding migration energy barrier is calculated, and, on the other hand, molecular dynamics calculations and kinetic Monte-Carlo simulations, for which the time evolution of the system is explicitly calculated. Introduction In nuclear materials, atomic transport properties can be a combination of radiation effects (atom collisions) and thermal effects (lattice vibrations), this latter being possibly enhanced by vacancies created by radiation damage in the crystal lattice (radiation enhanced-diffusion). Thermal diffusion usually occurs at high temperature (typically above 1 000 K in nuclear ceramics), which makes the transport processes difficult to model at lower temperatures because of the low probability to see the diffusion event occur in a reasonable simulation time. -

Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21St Century

Opportunities for Catalysis in The 21st Century A Report from the Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee BASIC ENERGY SCIENCES ADVISORY COMMITTEE SUBPANEL WORKSHOP REPORT Opportunities for Catalysis in the 21st Century May 14-16, 2002 Workshop Chair Professor J. M. White University of Texas Writing Group Chair Professor John Bercaw California Institute of Technology This page is intentionally left blank. Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................... v A Grand Challenge....................................................................................................... v The Present Opportunity .............................................................................................. v The Importance of Catalysis Science to DOE.............................................................. vi A Recommendation for Increased Federal Investment in Catalysis Research............. vi I. Introduction................................................................................................ 1 A. Background, Structure, and Organization of the Workshop .................................. 1 B. Recent Advances in Experimental and Theoretical Methods ................................ 1 C. The Grand Challenge ............................................................................................. 2 D. Enabling Approaches for Progress in Catalysis ..................................................... 3 E. Consensus Observations and Recommendations.................................................. -

![Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9440/solvent-effects-on-structure-and-reaction-mechanism-a-theoretical-study-of-2-2-polar-cycloaddition-between-ketene-and-imine-159440.webp)

Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: a Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition Between Ketene and Imine

J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 7877-7881 7877 Solvent Effects on Structure and Reaction Mechanism: A Theoretical Study of [2 + 2] Polar Cycloaddition between Ketene and Imine Thanh N. Truong Henry Eyring Center for Theoretical Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, UniVersity of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 ReceiVed: March 25, 1998; In Final Form: July 17, 1998 The effects of aqueous solvent on structures and mechanism of the [2 + 2] cycloaddition between ketene and imine were investigated by using correlated MP2 and MP4 levels of ab initio molecular orbital theory in conjunction with the dielectric continuum Generalized Conductor-like Screening Model (GCOSMO) for solvation. We found that reactions in the gas phase and in aqueous solution have very different topology on the free energy surfaces but have similar characteristic motion along the reaction coordinate. First, it involves formation of a planar trans-conformation zwitterionic complex, then a rotation of the two moieties to form the cycloaddition product. Aqueous solvent significantly stabilizes the zwitterionic complex, consequently changing the topology of the free energy surface from a gas-phase single barrier (one-step) process to a double barrier (two-step) one with a stable intermediate. Electrostatic solvent-solute interaction was found to be the dominant factor in lowering the activation energy by 4.5 kcal/mol. The present calculated results are consistent with previous experimental data. Introduction Lim and Jorgensen have also carried out free energy perturbation (FEP) theory simulations with accurate force field that includes + [2 2] cycloaddition reactions are useful synthetic routes to solute polarization effects and found even much larger solvent - formation of four-membered rings. -

Andrea Deoudes, Kinetics: a Clock Reaction

A Kinetics Experiment The Rate of a Chemical Reaction: A Clock Reaction Andrea Deoudes February 2, 2010 Introduction: The rates of chemical reactions and the ability to control those rates are crucial aspects of life. Chemical kinetics is the study of the rates at which chemical reactions occur, the factors that affect the speed of reactions, and the mechanisms by which reactions proceed. The reaction rate depends on the reactants, the concentrations of the reactants, the temperature at which the reaction takes place, and any catalysts or inhibitors that affect the reaction. If a chemical reaction has a fast rate, a large portion of the molecules react to form products in a given time period. If a chemical reaction has a slow rate, a small portion of molecules react to form products in a given time period. This experiment studied the kinetics of a reaction between an iodide ion (I-1) and a -2 -1 -2 -2 peroxydisulfate ion (S2O8 ) in the first reaction: 2I + S2O8 I2 + 2SO4 . This is a relatively slow reaction. The reaction rate is dependent on the concentrations of the reactants, following -1 m -2 n the rate law: Rate = k[I ] [S2O8 ] . In order to study the kinetics of this reaction, or any reaction, there must be an experimental way to measure the concentration of at least one of the reactants or products as a function of time. -2 -2 -1 This was done in this experiment using a second reaction, 2S2O3 + I2 S4O6 + 2I , which occurred simultaneously with the reaction under investigation. Adding starch to the mixture -2 allowed the S2O3 of the second reaction to act as a built in “clock;” the mixture turned blue -2 -2 when all of the S2O3 had been consumed. -

A Brief Introduction to the History of Chemical Kinetics

Chapter 1 A Brief Introduction to the History of Chemical Kinetics Petr Ptáček, Tomáš Opravil and František Šoukal Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.78704 Abstract This chapter begins with a general overview of the content of this work, which explains the structure and mutual relation between discussed topics. The following text provides brief historical background to chemical kinetics, lays the foundation of transition state theory (TST), and reaction thermodynamics from the early Wilhelmy quantitative study of acid-catalyzed conversion of sucrose, through the deduction of mathematical models to explain the rates of chemical reactions, to the transition state theory (absolute rate theory) developed by Eyring, Evans, and Polanyi. The concept of chemical kinetics and equilib- rium is then introduced and described in the historical context. Keywords: kinetics, chemical equilibrium, rate constant, activation energy, frequency factor, Arrhenius equation, Van’t Hoff-Le Châtelier’s principle, collision theory, transition state theory 1. Introduction Modern chemical (reaction) kinetics is a science describing and explaining the chemical reac- tion as we understand it in the present day [1]. It can be defined as the study of rate of chemical process or transformations of reactants into the products, which occurs according to the certain mechanism, i.e., the reaction mechanism [2]. The rate of chemical reaction is expressed as the change in concentration of some species in time [3]. It can also be pointed that chemical reactions are also the subject of study of many other chemical and physicochemical disciplines, such as analytical chemistry, chemical thermodynamics, technology, and so on [2]. -

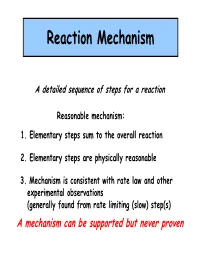

Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism A detailed sequence of steps for a reaction Reasonable mechanism: 1. Elementary steps sum to the overall reaction 2. Elementary steps are physically reasonable 3. Mechanism is consistent with rate law and other experimental observations (generally found from rate limiting (slow) step(s) A mechanism can be supported but never proven NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! NO2 + CO NO + CO2 2 Observed rate = k [NO2] Deduce a possible and reasonable mechanism NO2 + NO2 NO3 + NO slow NO3 + CO NO2 + CO2 fast Overall, NO2 + CO NO + CO2 Is the rate law for this sequence consistent with observation? Yes Does this prove that this must be what is actually happening? No! Note the NO3 intermediate product! Arrhenius Equation Temperature dependence of k kAe E/RTa A = pre-exponential factor Ea= activation energy Now let’s look at the NO2 + CO reaction pathway* (1D). Just what IS a reaction coordinate? NO2 + CO NO + CO2 High barrier TS for step 1 Reactants: Lower barrier TS for step 2 NO2 +NO2 +CO Products Products Bottleneck NO +CO2 NO +CO2 Potential Energy Step 1 Step 2 Reaction Coordinate NO2 + CO NO + CO2 NO22 NO NO 3 NO NO CO NO CO 222In this two-step reaction, there are two barriers, one for each elementary step. The well between the two transition states holds a reactive intermediate. -

Dehydrogenation by Heterogeneous Catalysts

Dehydrogenation by Heterogeneous Catalysts Daniel E. Resasco School of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science University of Oklahoma Encyclopedia of Catalysis January, 2000 1. INTRODUCTION Catalytic dehydrogenation of alkanes is an endothermic reaction, which occurs with an increase in the number of moles and can be represented by the expression Alkane ! Olefin + Hydrogen This reaction cannot be carried out thermally because it is highly unfavorable compared to the cracking of the hydrocarbon, since the C-C bond strength (about 246 kJ/mol) is much lower than that of the C-H bond (about 363 kJ/mol). However, in the presence of a suitable catalyst, dehydrogenation can be carried out with minimal C-C bond rupture. The strong C-H bond is a closed-shell σ orbital that can be activated by oxide or metal catalysts. Oxides can activate the C-H bond via hydrogen abstraction because they can form O-H bonds, which can have strengths comparable to that of the C- H bond. By contrast, metals cannot accomplish the hydrogen abstraction because the M- H bonds are much weaker than the C-H bond. However, the sum of the M-H and M-C bond strengths can exceed the C-H bond strength, making the process thermodynamically possible. In this case, the reaction is thought to proceed via a three centered transition state, which can be described as a metal atom inserting into the C-H bond. The C-H bond bridges across the metal atom until it breaks, followed by the formation of the corresponding M-H and M-C bonds.1 Therefore, dehydrogenation of alkanes can be carried out on oxides as well as on metal catalysts. -

Sustainable Catalysis

Green Process Synth 2016; 5: 231–232 Book review Sustainable catalysis DOI 10.1515/gps-2016-0016 Sustainable catalysis provides an excellent in-depth over- view of the applications of non-endangered elements in Michael North (Ed.) all aspects of catalysis from heterogeneous to homogene- Sustainable catalysis: with non-endangered metals ous, from catalyst supports to ligands. The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2015 Four volumes of the book series are divided into RSC Green Chemistry series nos. 38–41 two sub-topics devoted to (i) metal-based catalysts and Part 1 (ii) catalysts without metals or other endangered ele- Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-638-1 ments. Each sub-topic comprises of two books due to the PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-211-6 detailed analysis of catalytic applications described. All Part 2 chapters are written by the world-leading researchers in Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-639-8 the area; however, covering far beyond the scope of their PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-642-8 immediate research interests, which makes the book par- ticularly valuable for a wide range of readers. Sustainable catalysis: without metals or other Sustainable catalysis: with non-endangered metals endangered elements begins with a very brief chapter which describes the Part 1 concept of elemental sustainability, overviewing the Print ISBN: 978-1-78262-640-4 abundance of the critical elements and perspectives on PDF eISBN: 978-1-78262-209-3 sustainable catalysts. The chapters follow the groups of EPUB eISBN: 978-1-78262-752-4 the periodic table from left to right, from alkaline metals to Part 2 lead spanning 22 chapters. -

Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis

j1 Part I Principles of Enzyme Catalysis Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis, Third Edition. Edited by Karlheinz Drauz, Harald Groger,€ and Oliver May. Ó 2012 Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. Published 2012 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA. j3 1 Introduction – Principles and Historical Landmarks of Enzyme Catalysis in Organic Synthesis Harald Gr€oger and Yasuhisa Asano 1.1 General Remarks Enzyme catalysis in organic synthesis – behind this term stands a technology that today is widely recognized as a first choice opportunity in the preparation of a wide range of chemical compounds. Notably, this is true not only for academic syntheses but also for industrial-scale applications [1]. For numerous molecules the synthetic routes based on enzyme catalysis have turned out to be competitive (and often superior!) compared with classic chemicalaswellaschemocatalyticsynthetic approaches. Thus, enzymatic catalysis is increasingly recognized by organic chemists in both academia and industry as an attractive synthetic tool besides the traditional organic disciplines such as classic synthesis, metal catalysis, and organocatalysis [2]. By means of enzymes a broad range of transformations relevant in organic chemistry can be catalyzed, including, for example, redox reactions, carbon–carbon bond forming reactions, and hydrolytic reactions. Nonetheless, for a long time enzyme catalysis was not realized as a first choice option in organic synthesis. Organic chemists did not use enzymes as catalysts for their envisioned syntheses because of observed (or assumed) disadvantages such as narrow substrate range, limited stability of enzymes under organic reaction conditions, low efficiency when using wild-type strains, and diluted substrate and product solutions, thus leading to non-satisfactory volumetric productivities.