Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM 1. Name of Property historic name: Dearborn River High Bridge other name/site number: 24LC130 2. Location street & number: Fifteen Miles Southwest of Augusta on Bean Lake Road not for publication: n/a vicinity: X city/town: Augusta state: Montana code: MT county: Lewis & Clark code: 049 zip code: 59410 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this _X_ nomination _ request for detenj ination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the proc urf I and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criterfi commend thatthis oroperty be considered significant _ nationally X statewide X locafly. Signa jre of oertifying officialn itle Date Montana State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency or bureau (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments. In my opinion, the property _ meets _ does not meet the National Register criteria. Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. National Park Service Certification , he/eby certify that this property is: 'entered in the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined eligible for the National Register _ see continuation sheet _ determined not eligible for the National Register_ _ see continuation sheet _ removed from the National Register _see continuation sheet _ other (explain): _________________ Dearborn River High Bridge Lewis & Clark County. -

The Lewis and Clark Trail

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 1969 THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark "THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL" (1969). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 166. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/166 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL FINAL REPORT of the Lewis and Clark Trail COIIlInission October 1969 THE EMBLEM The emblem on the cover was the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission's official symbol and became the property of the Department of the Interior after the Commission terminated on October 6, 1969. A modification of this mark has been used to identify highways that have been designated by the States as the Lewis and Clark Trail Highway, and on signs that interpret the Trail. Information regarding use of the symbol, u.S. Patent Office Registration Number 877917, may be obtained from the Secretary, Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL FINAL REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT AND TO THE CONGRESS The Lewis and Clark Trail Commission October 1969 Dear Mr. President and Members of the Congress: It is with great pleasure that the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission submits its third and final report on the accomplishments made in response to the objectives of Public Law 88-630. -

Botanical Illustrations of Plants Found by Merriwether Lewis

On the Trail with Lewis and Clark Botanical Illustrations of plants found by Merriwether Lewis by Ms. Amatucci's Fourth Graders Stony Point May 2004 The Process Fourth grade students in Albemarle County study Virginia History in social studies. This year there has been a special emphasis on Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery. May 2004 marks the bi-centennial of the beginning of the expedition to the northwest. Students also study plant parts and plant reproduction as part of the science curriculum. This project was an integration of social studies and science content with art, mathematics, and technology. Each student selected a plant or flower found along the expedition trail and then researched where the plant was observed and/or collected. As part of his scientific duties, Merriwether Lewis observed plants, illustrated them, and recorded botanical descriptions. Our journey started at the Lewis-Ginter Botanical Gardens in Richmond, Virginia, where we had our first lesson in botanical illustration. We learned that botanical illustration is the merging of scientific and mathematical observation and artistic skill. Using watercolors requires drawing, design and color skills. We brainstormed a list of plants after visiting the website http://www.life.umd.edu/emeritus/reveal/pbio/LnC/LnCpublic.htm. We each chose a different plant. We spent time researching and recorded where it was observed or collected; the town, county, state, and date. We also learned the botanical name as well as the common name. After a preliminary sketch, we learned how to transfer our drawing on to watercolor paper. Some of us learned how to manipulate images on the copy machine. -

The Lewis and Clark Trail

THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL FINAL REPORT of the Lewis and Clark Trail COIIlInission October 1969 THE EMBLEM The emblem on the cover was the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission's official symbol and became the property of the Department of the Interior after the Commission terminated on October 6, 1969. A modification of this mark has been used to identify highways that have been designated by the States as the Lewis and Clark Trail Highway, and on signs that interpret the Trail. Information regarding use of the symbol, u.S. Patent Office Registration Number 877917, may be obtained from the Secretary, Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. THE LEWIS AND CLARK TRAIL FINAL REPORT TO THE PRESIDENT AND TO THE CONGRESS The Lewis and Clark Trail Commission October 1969 Dear Mr. President and Members of the Congress: It is with great pleasure that the Lewis and Clark Trail Commission submits its third and final report on the accomplishments made in response to the objectives of Public Law 88-630. Interim reports were submitted October 1966 and June 1968. Congress' mandate to the Commission was to stimulate a creative and viable atmosphere for all agencies and individuals to identify, mark, and preserve for public use and enjoyment the routes traveled by Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. An assignment of this nature is never completed. Yet, by encouraging dialogue and by promoting cooperation and long-range planning, the Commission achieved a new sense of purpose and unity among the States traversed by the two explorers and their men. -

March 2021 Don Peterson Supplement

The LCTHF mourns the passing of longtime member Don Peterson. He was a leader of the Portage Route Chapter (PRC) and an authority on Lewis and Clark in central Montana. Don’s wife Cherie related a brief history of Don’s life to Lee Ebeling, Harry Mitchell, and Bill Bronson at her home on January 8, 2021, which Lee recorded as follows: Don was born on June 17, 1945, in New Rockford, ND, to Norwegian parents. His family moved to Great Falls when Don was about five years old. He was graduated from Great Falls High School in 1963 and attended College of Great Falls. After working briefly for Safeway markets, Don took a position with the Montana Air National Guard (MANG). During his 30- year career there, Don served in munitions, Don Peterson on a hike up to Cape Disappointment at the missiles, base supply, and as LCTHF's 2018 Annual Meeting in Astoria, OR. Photo by Lee communications head. He retired as a major Ebeling from MANG, having been a dual military and civilian employee. Don met his wife Cherie on a blind date in 1963. They were married in October 1965 and have two children, Eric of Lake Bay, WA, and Beth of Great Falls, and several grandchildren. Don also operated a Lewis and Clark tour business in Great Falls for many years. Having begun his Lewis and Clark affiliation in 1991, he wrote two books and many articles on the Lewis and Clark story in Great Falls and filled in as the LCTHF’s interim executive director during a transition period. -

TEWIS and CLARJ^ Tribes of the Region

In 1800, the Rocky Mountains of northwestern Jefferson chose his private secretary, Captain Meriwether cached a good deal of the baggage they could do without until they re obtained sap and the soft part of the wood and bark for food. THE THREE FORKS United States was a land known only by the Indian Lewis, to lead the party. In turn, Lewis chose William Clark turned from the ocean. Meanwhile Lewis and the main party were using tow lines and poles to Clark's advance party had reached the Three Forks of the On June 13, Lewis and a small party, which had gone ahead of the boats, ascend the evermore challenging Missouri. On July 19 they reached the TEWIS AND CLARJ^ tribes of the region. The portion of the Rockies east of Louisville, Kentucky, one of his former commanding offi Missouri (13) on July 25. They saw the prairie had recently been cers, to be his co-commander. Lewis spent several weeks in reached the Great Falls of the Missouri (2). Rather than one waterfall, as "most remarkable cliffs" they had yet seen. It looked as though the river burned, and there were horse tracks which appeared to be only a few they had anticipated, there was a series of five cascades around which they had worn a passage just the width of its channel through these 1200-foot- •^^'IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS--*- ^" of the Continental Divide became U.S. territory in Philadelphia studying science, medicine, surveying, and in days old. Clark left a note for Lewis telling him he was going to con would have to portage boats and baggage. -

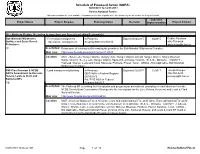

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 Helena National Forest This Report Contains the Best Available Information at the Time of Publication

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 Helena National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact R1 - Northern Region, Occurring in more than one Forest (excluding Regionwide) Bob Marshall Wilderness - Recreation management In Progress: Expected:04/2015 04/2015 Debbie Mucklow Outfitter and Guide Permit - Special use management Scoping Start 03/29/2014 406-758-6464 Reissuance [email protected] CE Description: Reissuance of existing outfitter and guide permits in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=44827 Location: UNIT - Swan Lake Ranger District, Hungry Horse Ranger District, Lincoln Ranger District, Rocky Mountain Ranger District, Seeley Lake Ranger District, Spotted Bear Ranger District. STATE - Montana. COUNTY - Flathead, Glacier, Lewis and Clark, Missoula, Pondera, Powell, Teton. LEGAL - Not Applicable. Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex. FNF Plan Revision & NCDE - Land management planning In Progress: Expected:12/2017 12/2017 Joseph Krueger GBCS Amendment to the Lolo, DEIS NOA in Federal Register 406-758-5243 Helena, Lewis & Clark,and 06/03/2016 [email protected] Kootenai NFs Est. FEIS NOA in Federal EIS Register 04/2017 Description: The Flathead NF is revising their forest plan and preparing an amendment providing relevant direction from the NCDE Grizzly Bear Conservation Strategy into the forest plans for the Lolo, Helena, Kootenai, and Lewis & Clark National Forests. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/goto/flathead/fpr Location: UNIT - Kootenai National Forest All Units, Lewis And Clark National Forest All Units, Flathead National Forest All Units, Helena National Forest All Units, Lolo National Forest All Units. -

GOLD WEST COUNTRY 2012 TRAVEL PLANNER Mount Ascension, Helena (Tom Robertson) the Montana You Have in Mind Is the One We Have in Store

goldwest.visitmt.com | 800.879.1159 VISITOR’S GUIDE TO THE BEST OF MONTANA GOLD WEST COUNTRY 2012 TRAVEL PLANNER Mount Ascension, Helena (Tom Robertson) THE MONTANA YOU HAVE IN MIND IS THE ONE WE have IN store. When you think of Montana, what do you picture? Skyscraping ranges of snowcapped rock? Historic, cultural centers that tell of a proud, self-determined West? A cowboy tipping his hat to you as he passes by on a boardwalk? Herds of elk grazing in waist-deep bunch grass? A sky so wide it seems to swallow you up? Then you’re picturing Gold West Country, a stretch of Southwest Montana we humbly claim holds the best of what Montana is about. Its spirit, wildness, culture and charm. Its stunning beauty. Gold West Country is one of six tourism regions in the state. We are situated on the route from Yellowstone National Park to Glacier National Park. At our northern end sits the cowboy town of Augusta with its famed rodeo. At our center are Helena and Butte, cornerstones of Montana’s history. Our south is the famed Trout Triangle, a who’s who and what’s what of trout fishing and outdoor pursuits. (Donnie Sexton) Antelope (John Belobraidic) WWW.GOLDWEST.VISITMT.COM 1 AMID IT ALL, you’ll meet a diverse mix of friendly people — hoteliers, restaurateurs, shopkeepers, historians, ranchers, miners, fly anglers, cowboys (and girls) and more. You’ll have opportunities to glimpse the same wildlife Lewis and Clark marveled at more than two centuries ago — elk, black bears, mule deer, moose, golden eagles and perhaps even a gray wolf. -

Appendices (PDF)

Appendices Appendix A: Background Information for the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................. 3 The Expedition: Making Ready ................................................................................................................................. 3 List of Supplies .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Timeline for the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................................................. 9 Map of the Westward Route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................ 19 Map of the Eastbound Route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ............................................................................ 20 The Expedition: Putting Away ................................................................................................................................ 21 Appendix B: People of the Lewis and Clark Expedition ....................................................................................... 23 President Thomas Jefferson ................................................................................................................................... 23 Captain Meriwether Lewis (Co-Leader) .................................................................................................................. 24 Seaman (Dog and Expedition -

Montana and Idaho Day & Overnight Hikes Guide

CONTINENTAL DIVIDE NATIONAL SCENIC TRAIL DAY & OVERNIGHT HIKES: IDAHO & MONTANA Photo by Steven Shattuck CONTINENTAL DIVIDE TRAIL COALITION VISIT IDAHO & MONTANA! Day & Overnight Hikes on the CDT THE GEM STATE AND THE TREASURE STATE Montana, known as “The Treasure State” and “Big Sky Country,” and Idaho, “The Gem State,” offer many wonderful Continental Divide Trail (CDT) experiences! The trail meanders along the southern border of Montana and eastern border of Idaho and extends for 1,012 miles through the two states, running through the present-day and ancestral lands of numerous Native American tribes including the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Ktunaxa, Eastern Shoshone, Lemhi Shoshone, Shoshone-Bannock, Salish Kootenai, and Tsuu T’ina tribes. In these states you’ll find mountain goats, grizzly bears, wolves, and bald eagles, as well as douglas fir, lodgepole pine, aspen, lady-slipper, buttercups, beargrass, and glacier lilies. We’ve put together this list of the best day and overnight hikes on the CDT in Montana and Idaho for you to explore some of our favorite parts of the trail! Hikes in this guide are listed from south to north. WILDLIFE: Idaho and Montana have both black bears and grizzly bears, each with distinct characteristics and behaviors. We recommend learning more about best practices while hiking in bear country. If you plan on hiking, make sure you are prepared with bear spray. MOUNTAIN WEATHER: Snow can stay in the high mountains long into the summer. Remember that you likely won’t be able to get to the higher trails during the winter and spring. Additionally, mountain weather can change drastically and unpredictably. -

Giant Mural Portrays Lewis and Clark Portage of the Great Falls of the Missouri

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE LEWIS & CLARK TRAIL HERITAGE FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 10, NO. 4 NOVEMBER 1984 Giant Mural Portrays Lewis and Clark Portage of the Great Falls of the Missouri Unveiling Ceremony Exciting Event at Foundation's 16th Annual Meeting Immediately preceding the Foundation's 16th Annual Banquet, there was a pertinent activity gra ciously planned to coincide with the Foundation's Annual Meeting by the city of Great Falls Centennial Committee. This was the unveiling ceremony in the upper level of the Great Falls International Airport. Nearly one thousand individuals attended the event. The work of Montana artist Robert Orduiio, the mural pictures the struggle of the members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition as they effected the strenuous ordeal of accomplishing the portage around the natural barrier - the series of falls that restricted their passage on the Missouri River. The mural was made possible by a substantial grant from the Burlington Northern Foundation. A representative of that Foundation, Montana Governor Ted Schwinden, state and civic officials, and art connoissuers, who spoke briefly, were joined by both the president and the president-elect of our Foundation, and their remarks are transcribed here: (See also, the related story on page 7) 1983-1984 Foundation President Arlen J. Large's re· 1984-1985 Foundation President William P. Sherman's marks made at the August 8, 1984 unveiling ceremony remarks made at the August 8, 1984 unveiling cere of the mural: mony for the mural: Thanks to our Foundation members in Great Falls, we Last November a competition was held to pick the outsiders have seen the actual geography of the 1805 artist for this great mural. -

The Dearborn River Confluence: Montana’S Northwest Passage

91 The Dearborn River Confluence: Montana’s Northwest Passage John B. Wright river route to the Pacific was the dream of Thomas Jefferson1— manifest transit for “Louisiana” furs and Canton silks. This opti- Amism was crushed when Meriwether Lewis reported to the Presi- dent that a 340-mile portage was needed from the Missouri to the Co- lumbia rivers, including 140 arduous miles of “the most formidable part of the tract...(over) tremendous mountains which for 60 mls. are covered with eternal snows.”2 Stephen Ambrose put it succinctly, “With those words, Lewis put an end to the search for the Northwest Passage.”3 But should it have been? For large ships, certainly, but for the pirogues, canoes, and shallow- draft keel boats that would dominate river travel in the region for the next fifty years? Absolutely not. While any crossing of the Continental Divide required some overland portage, the expedition never comprehended how short such a transfer could have been. The journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the landscape of Montana reveal an overlooked confluence with the Missouri—the Dearborn River—that, if appreciated, might have changed the historical geography of the Louisiana Territory and beyond. In fact, a kind of Northwest Passage did exist. At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, America was almost entirely dependent on rivers and coastal waters for travel and trade. Fall-line cities from New Haven to Macon grew at the heads of navigation. Coastal cities grew at good harbors. Canal building would become a national craze. Waterways were transportation and prior to the coming of the railroads; no viable commercial alternatives existed.