UF00007184 ( .Pdf )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

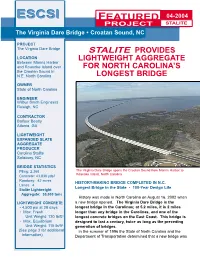

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

APPENDIX A: Interview Guides for Participants

ABSTRACT DIAL, HEATHER KIMBERLY BARTON. Struggling for Voice in a Black and White World: Lumbee Indians’ Segregated Educational Experience in North Carolina. (Under the direction of Patricia L. Marshall, Ed.D. and Anna V. Wilson, Ph.D.) This study investigates the North Carolina Lumbee Indians’ segregated educational experience in North Carolina from 1885 to 1970. This oral history documents the experiences of the Lumbee Indians in the segregated Indian schools and adds their voices to the general discourse about Indian schools in our nation and to the history of education. The sample for this research included six members of the Lumbee community who experienced education in the segregated Indian schools in Hoke and Robeson Counties of southern North Carolina. My oral history research involved interviews with individuals who experienced the role of teachers, students, and administrators. A network selection sampling procedure was used to select participants. The main data sources were the participants’ oral educational histories. Limited archival research (e.g., board of education minutes) supports the final analysis. An analysis method for categorizing and classifying data was employed. The analysis method is similar to the constant comparative method of data analysis. Major findings show that the Lumbee students not only experienced a culturally supportive education, but also experienced a resource poor environment in the segregated Indian schools. Conversely, desegregation provided increased equity in educational resources and educational opportunities for the Lumbee students which unfortunately resulted in a loss of community, identity, and diminished teacher-student connection. Findings indicate the participants were aware of the role of segregation in the larger societal context. -

U Ni Ted States Departmen T of the Interior

Uni ted States Departmen t of the Interior BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS WASHINGTON, D.C. 20245 • IN REPLY REFER TO; MAR 281984. Tribal Government ;)ervices-F A MEMORANDUM To: A!:sistant Secretary - Indian Affairs From: DE!Puty Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs (Operations) Subject: Rc!cornmendation and Summary of Evidence for Proposed Finding Against FE!deral Acknowledgment of the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc. Pursuant to 25 CFR 83. Recom mendatiol We recommend thut the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc • (hereinafter "UGN") not be acknowledged as an Indian tribe entitled to a government to-government ]'elationship with the United States. We further recommend that a letter of the proposecl dc:!termination be forwarded to the ULN and other interested parties, • and that a notiC!e of the proposed finding that they do not exist as an Indian tribe be published in th4~ P,ederal Register. General Conclusions The ULN is a recently formed organization which did not exist prior to 1976. The organization WHS c!onceived, incorporated and promoted by one individual for personal interests and ,Ud not evolve from a tribal entity which existed on a substantially continuous bash from historical times until the present. The ULN has no relation to the Lumbees of the Robeson County area in North Carolina (hereinafter "Lumbees") historically soci.ally, genealogically, politically or organizationally. The use of the name "Lumbee" by Ule lILN appears to be an effort on the part of the founder, Malcolm L. Webber (aka Chief Thunderbird), to establish credibility in the minds of recruits and outside organiz Ilticlns. -

We've Wondered, Sponsored Two Previous Expeditions to Roanoke Speculated and Fantasized About the Fate of Sir Island

/'\ UNC Sea Grant June/July, 7984 ) ,, {l{HsT4IIHI'OII A Theodor de Bry dtawin! of a John White map Dare growing up to become an Indian princess. For 400 yearS, Or, the one about the Lumbee Indians being descendants of the colonists. Only a few people even know that Raleigh we've wondered, sponsored two previous expeditions to Roanoke speculated and fantasized about the fate of Sir Island. Or that those expeditions paved the way Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony. What happened to for the colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth. the people John White left behind? Historians This year, North Carolina begins a three-year and archaeologists have searched for clues. And celebration of Raleigh's voyages and of the people still the answers elude us. who attempted to settle here. Some people have filled in the gaps with fic- Coastwatc.tr looks at the history of the Raleigh tionalized.accounts of the colonists' fate. But ex- expeditions and the statewide efforts to com- perts take little stock in the legend of Virginia memorate America's beginnings. In celebration of the beginning an July, the tiny town of Manteo will undergo a transfor- Board of Commissioners made a commitment to ready the I mation. In the middle of its already crowded tourist town for the anniversary celebration, says Mayor John season, it will play host for America's 400th Anniversary. Wilson. Then, the town's waterfront was in a state of dis- Town officials can't even estimate how many thousands of repair. By contrast, at the turn of the century more than people will crowd the narrow streets. -

CFSA Business & Nonprofit Membership Directory

Shepherds CFSA Business Members March 2020 Brooks Contractor | brookscontractor.com Commercial, family-owned composter offering roll-off service, food waste composting, compost and topsoil blends, and horse manure composting. Based in Goldston, NC. Clean Green Environmental Services | cleangreennc.com Environmental waste management services to Raleigh-Durham and beyond, including waste oil recovery, antifreeze recovery, used oil filter recycling, environmental remediation, and more. eHungry, Inc. | ehungry.com eHungry provides restaurants with the ability to take online orders through a customizable online menu and branded mobile apps. Santa Fe Natural Tobacco | sfntc.com Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company share a values-driven vision: that our uncompromising commitment to our real tobacco products, the earth from which they come, the communities on which we depend, and the people who bring our spirit to life is essential to our success. TS Designs | tsdesigns.com TS Designs is a screen printing company committed to sustainability. We offer unique t-shirt brands that focus on local, transparent supply chains. Based in Burlington, NC. Weaver Street Market | weaverstreetmarket.coop Community-owned natural foods grocery store with locations in Carrboro, Southern Village in Chapel Hill, and Hillsborough, NC. Whole Foods Market | wholefoodsmarket.com Our purpose is to nourish people and the planet. We’re a purpose-driven company that aims to set the standards of excellence for food retailers. Quality is a state of mind at Whole Foods Market. -

Read Penne Smith's Research on Island Farm

ILLUSTRATIONS TO TEXT Fig. 1: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House, front elevation, ca. 1945 (at present site; original porch removed). Paneled door is original. Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. Fig. 2: Meekins Homeplace, side elevation ca. 1915. D. Victor Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC Fig. 3: Christaina (“Crissy”) Bowser, ca. 1910. D. Victor Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. N.B. The simple stoop entrance and rough board-and-batten exterior in the background; this has been assumed to have been Crissy Bowser’s cabin on the Etheridge Farm. Fig. 4: Thomas A. Dough, Grave Marker. Etheridge Family Cemetery, Manteo, NC (Penne Smith, 1999 photograph) Fig. 5: Detail of Thomas A. Dough Grave Marker (Penne Smith, 1999 photograph) Fig. 6: Aufustus H. Etheridge Business Card, 1907. Etheridge Family Collection, Outer Banks Conservationists, Inc. Fig. 7: Front elevation of Etheridge House, May 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) Fig. 8: 1890s rear ell of Etheridge House, May 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) Fig. 9: Capt. L. J. Pugh House, Wanchese, NC, July 1999 (Penne Smith, photographer) This graceful Victorian farmhouse may have been what the Etheridge 1890s rrenovation aspired to. Fig. 11: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House, front and side elevations, ca. 1940. Roger Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC Fig. 13: Dough-Hayman-Drinkwater House,rear and side elevations, ca. 1940. Roger Meekins Collection, Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC. N.B. the door surround at the side elevation. Fig. 14: United States Coast Guard, 1957 aerial map of Roanoke Island, detail of Etheridge Homeplace farmstead. Cartography Division, National Archives, College Park, MD Fig. -

Conflict, Crisis, and Violence in the Virginia Coastal Lands

REDUCTIVE RIPPLES IN THE NEW WORLD: CONFLICT, CRISIS, AND VIOLENCE IN THE VIRGINIA COASTAL LANDS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS IN HISTORY MAY 2016 By Mark D. Shoberg Thesis Committee: Richard Rath, Chairperson Suzanna Reiss Marcus Daniel Keywords: Violent Transformation, Reduction, Reducción, Algonquians, Roanoke, Jamestown, Ajacán, Powhatan, Don Luis, Scarcity, Accumulation Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Argument ......................................................................................................... 2 Reductivism ..................................................................................................... 4 Ambivalence .................................................................................................... 6 Reducción......................................................................................................... 7 Scarcity ............................................................................................................ 9 Mapping ......................................................................................................... 10 Christian Religious Ideologies ....................................................................... 12 Structure of Thesis ........................................................................................ -

Bookletchart™ Cape May to Cape Hatteras NOAA Chart 12200

BookletChart™ Cape May to Cape Hatteras NOAA Chart 12200 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the There are no deepwater ports along this stretch of the coast. Oregon, Hatteras, and Ocracoke Inlets provide the main entrances to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shallow, sandy-bottom waters behind The Outer Banks. These inlets are National Ocean Service used principally by fishing vessels. Office of Coast Survey Discussed in this chapter are the waters of Albemarle Sound and its tributaries Little, Perquimans, Chowan, and Roanoke Rivers, and the www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov towns of Hertford, Edenton, and Plymouth; Croatan and Roanoke 888-990-NOAA Sounds, Roanoke Island, and the towns of Kitty Hawk, Nags Head, Manteo, and Wanchese; Pamlico Sound and the towns of Rodanthe, What are Nautical Charts? Avon, Buxton, Hatteras, and Ocracoke which are on the western side of The Outer Banks; Pamlico River and the towns of Swanquarter, Bath, Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show and Washington; Neuse River and the town of New Bern; and Core water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Sound, Cedar Island, and the towns of Atlantic, Sealevel, Davis, and more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Marshallberg. These ports and waters support considerable traffic in efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial barges and pleasure craft, and a large fishing and boatbuilding industry. ships that carry America’s commerce. They are also used on every Navy There are many off-lying shoals and other hazards along this coast and Coast Guard ship, fishing and passenger vessels, and are widely including Diamond Shoals and Cape Lookout Shoals. -

Conserving Skeletal Material in Eroding Shorelines, Currituck

WEAPEMEOC SHORES: THE LOSS OF TRADITIONAL MARITIME CULTURE AMONG THE WEAPEMEOC INDIANS by Whitney R. Petrey April, 2014 Director of Thesis: Larry Tise, PhD Major Department: Maritime Studies The Weapemeoc were an Indian group of the Late Woodland Period through the Early Colonial Period (1400 A.D.-1780 A.D.) that went through significant cultural change as they were displaced from their traditional maritime subsistence resources. The Weapemeoc were located in what is today northeastern North Carolina. Their permanent villages were located along the northern shore of Albemarle Sound, with seasonal and temporary villages on the outer banks and upriver on the several tributaries that drain to the Albemarle Sound. Weapemeoc access to maritime resources would be altered significantly by European colonization and settlement in the area. The loss of maritime subsistence, maritime communication and maritime mentality resulted in the loss of the traditional culture of the Weapemeoc Indians and their seeming disappearance as a distinct group of people. Early historical records and maps illustrate the acculturation of the Weapemeoc and the loss of traditional maritime culture. As land was sold to settlers in prime areas along rivers and along the shore of the Albemarle Sound, Weapemeoc were displaced from their seasonal procurement sites and seasonal permanent villages. By 1704, a reservation was established by the colonial government for the Weapemeoc along Indiantown Creek. By 1780, the Weapemeoc lived in such a similar fashion as their neighbors of European descent that they are no longer distinguishable in the archaeological or historical record. WEAPEMEOC SHORES: THE LOSS OF TRADITIONAL MARITIME CULTURE AMONG THE WEAPEMEOC INDIANS A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of History East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts In Maritime Studies by Whitney R. -

The Scuppernong River Project: Explorations of Tyrrell County Maritime History

THE SCUPPERNONG RIVER PROJECT: VOLUME 1 EXPLORATIONS OF TYRRELL COUNTY MARITIME HISTORY Nathan Richards, Daniel Bera, Saxon Bisbee, John Bright, Dan Brown, David Buttaro, Jeff O’Neill and William Schilling i Research Report No. 21 THE SCUPPERNONG RIVER PROJECT: VOLUME 1 EXPLORATIONS OF TYRRELL COUNTY MARITIME HISTORY By Nathan Richards Daniel Bera Saxon Bisbee John Bright Dan Brown David Buttaro Jeff O’Neill William Schilling 2012 © The PAST Foundation ISBN 978-1-939531-00-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012955595 Series Editor: Nathan Richards, Program in Maritime Studies, East Carolina University, Admiral Ernest M. Eller House, Greenville, North Carolina, 27858. Cover: Portion of the James Wimble map of North Carolina (1738) showing location of the Scuppernong River (North Carolina State Archives). Cover design concept: Nadine Kopp. ii DEDICATION This publication is dedicated to the people of Columbia, for their unwavering hospitality during the 2011 Scuppernong River Project. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project and the products that have emerged from it would not have been possible without the assistance of a congregation of people from a host of institutions across eastern North Carolina. From the outset, this project was designed with collaboration at its core. In investigating the history and archaeology of Tyrrell County, we wanted this to be a project that left something for the people of the area to have once we packed up and returned from where we came. We hope that our work lives up to their expectations. At the UNC-Coastal Studies Institute, John McCord and David Sybert were involved in every facet of the project; not only did they coordinate local outreach and education events (in conjunction with Lauren Heesemann, NOAA) and film activities for a short documentary, but they also “took the plunge” when instrumentation disappeared into the tea-stained Scuppernong. -

Lumbee Recognition Act” Before the House Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples of the United States

TESTIMONY OF PRINCIPAL CHIEF RICHARD SNEED EASTERN BAND OF CHEROKEE INDIANS A HEARING ON H.R. 1964, THE “LUMBEE RECOGNITION ACT” BEFORE THE HOUSE SUBCOMMITTEE FOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF THE UNITED STATES December 4, 2019 Chairman Gallego, Leader Cook, members of the Indigenous Peoples of the United States Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today to provide the views of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians on H.R. 1964, the “Lumbee Recognition Act.” For over a century, the Lumbees in North Carolina have sought federal recognition as an Indian tribe, which, under federal law, should be an Indigenous people with a governing body that preexisted the founding of the United States.1 The Lumbees have falsely claimed to be a Cherokee tribe, and groups and individuals within the Lumbee continue to appropriate our Cherokee identity. But the Cherokees are not the only tribal identity that the Lumbees have sought to falsely appropriate. They have cloaked themselves in the identities of many other tribes in trying to achieve acknowledgment as a tribe from the federal government. Even since the last Congress, the Lumbees have changed from identifying themselves as the “Lumbee Tribe of Cheraw Indians” to the more general “Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina,” described as an amalgamation of tribes based on general dialects—not specific historic tribes with identifiable governing bodies. As you may know, Lumbee is not an historical tribe but a derivation of the word “Lumber” from the Lumbee location near the Lumber River. Finally, based on the research of third-party experts, we do not believe that most Lumbees today can demonstrate any Native ancestry at all, and this bill seeks to prevent a substantive review of this fact. -

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: Preservation and Recognition, C

CONTENTS Figure Credits iv List of Figures V Foreword vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Chapter One: The Roanoke Colonies and Fort Raleigh, c. 1584-1590 9 Associated Properties 28 Registration Requirements/Integrity 29 Contributing Resources 30 Potentially Eligible Archeological Resources 30 Chapter Two: The Settlement and Development of Roanoke Island, c. 1650-1900 31 Associated Properties 54 Registration Requirements/Integrity 55 Noncontributing Resources 57 Potentially Eligible Archeological Resources 57 Chapter Three: Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: Preservation and Recognition, c. 1860-1953 59 Associated Properties 91 Registration Requirements/Integrity 93 Contributing Resources 97 Noncontributing Resources 97 Potentially Eligible Archeological Resources 97 Management Recommendations 99 Bibliography 101 Appendix A: Descriptions of Historic Resources A-l Appendix B: Property Map/Historical Base Map B-l Appendix C: National Register Documentation C-1 Index D-l iii FIGURE CREDITS Cover, 15, 17, 22: courtesy of Harpers Ferry Center, National Park Service; pp. 10, 12, 13, 16, 23: Charles W. Porter III, Adventurers to a New World; pp. 22, 27: Theodore De Bry, Thomas Hariot’s Virginia; pp. 35,39,41: courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, Manteo, NC; pp. 37, 38: Samuel H. Putnam, The Story of Company A, Twenty-Fifth Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers, in the War of the Rebellion; p. 43: Vincent Colyer, Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army, in North Carolina; pp. 44, 46, 47: Joe A. Mobley, James City, A Black Community in North Carolina, 1863-1900; pp. 55, 67, 81: S. Bulter for the National Park Service; pp. 61, 66, 78: William S.