Red States Series Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

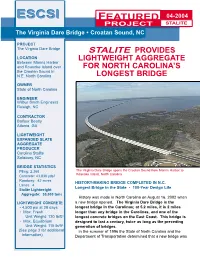

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Site 3 40 Acre Rock

SECTION 3 PIEDMONT REGION Index Map to Study Sites 2A Table Rock (Mountains) 5B Santee Cooper Project (Engineering & l) 2B Lake Jocassee Region (Energy 6A Congaree Swamp (Pristine Forest) Produ tion) 3A Forty Acre Rock (Granite 7A Lake Marion (Limestone Outcropping) Ot i ) 3B Silverstreet (Agriculture) 8A Woods Bay (Preserved Carolina Bay) 3C Kings Mountain (Historical 9A Charleston (Historic Port) Battleground) 4A Columbia (Metropolitan Area) 9B Myrtle Beach (Tourist Area) 4B Graniteville (Mining Area) 9C The ACE Basin (Wildlife & Sea Island ulture) 4C Sugarloaf Mountain (Wildlife Refuge) 10A Winyah Bay (Rice Culture) 5A Savannah River Site (Habitat 10B North Inlet (Hurricanes) Restoration) TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR SECTION 3 PIEDMONT REGION - Index Map to Piedmont Study Sites - Table of Contents for Section 3 - Power Thinking Activity - "The Dilemma of the Desperate Deer" - Performance Objectives - Background Information - Description of Landforms, Drainage Patterns, and Geologic Processes p. 3-2 . - Characteristic Landforms of the Piedmont p. 3-2 . - Geographic Features of Special Interest p. 3-3 . - Piedmont Rock Types p. 3-4 . - Geologic Belts of the Piedmont - Influence of Topography on Historical Events and Cultural Trends p. 3-5 . - The Catawba Nation p. 3-6 . - figure 3-1 - "Great Seal and Map of Catawba Nation" p. 3-6 . - Catawba Tales p. 3-6 . - story - "Ye Iswa (People of the River)" p. 3-7 . - story - "The Story of the First Woman" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Woman Who Became an Owl" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Legend of the Comet" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Legend of the Brownies" p. 3-8 . - story - "The Rooster and the Fox" p. -

APPENDIX A: Interview Guides for Participants

ABSTRACT DIAL, HEATHER KIMBERLY BARTON. Struggling for Voice in a Black and White World: Lumbee Indians’ Segregated Educational Experience in North Carolina. (Under the direction of Patricia L. Marshall, Ed.D. and Anna V. Wilson, Ph.D.) This study investigates the North Carolina Lumbee Indians’ segregated educational experience in North Carolina from 1885 to 1970. This oral history documents the experiences of the Lumbee Indians in the segregated Indian schools and adds their voices to the general discourse about Indian schools in our nation and to the history of education. The sample for this research included six members of the Lumbee community who experienced education in the segregated Indian schools in Hoke and Robeson Counties of southern North Carolina. My oral history research involved interviews with individuals who experienced the role of teachers, students, and administrators. A network selection sampling procedure was used to select participants. The main data sources were the participants’ oral educational histories. Limited archival research (e.g., board of education minutes) supports the final analysis. An analysis method for categorizing and classifying data was employed. The analysis method is similar to the constant comparative method of data analysis. Major findings show that the Lumbee students not only experienced a culturally supportive education, but also experienced a resource poor environment in the segregated Indian schools. Conversely, desegregation provided increased equity in educational resources and educational opportunities for the Lumbee students which unfortunately resulted in a loss of community, identity, and diminished teacher-student connection. Findings indicate the participants were aware of the role of segregation in the larger societal context. -

U Ni Ted States Departmen T of the Interior

Uni ted States Departmen t of the Interior BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS WASHINGTON, D.C. 20245 • IN REPLY REFER TO; MAR 281984. Tribal Government ;)ervices-F A MEMORANDUM To: A!:sistant Secretary - Indian Affairs From: DE!Puty Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs (Operations) Subject: Rc!cornmendation and Summary of Evidence for Proposed Finding Against FE!deral Acknowledgment of the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc. Pursuant to 25 CFR 83. Recom mendatiol We recommend thut the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc • (hereinafter "UGN") not be acknowledged as an Indian tribe entitled to a government to-government ]'elationship with the United States. We further recommend that a letter of the proposecl dc:!termination be forwarded to the ULN and other interested parties, • and that a notiC!e of the proposed finding that they do not exist as an Indian tribe be published in th4~ P,ederal Register. General Conclusions The ULN is a recently formed organization which did not exist prior to 1976. The organization WHS c!onceived, incorporated and promoted by one individual for personal interests and ,Ud not evolve from a tribal entity which existed on a substantially continuous bash from historical times until the present. The ULN has no relation to the Lumbees of the Robeson County area in North Carolina (hereinafter "Lumbees") historically soci.ally, genealogically, politically or organizationally. The use of the name "Lumbee" by Ule lILN appears to be an effort on the part of the founder, Malcolm L. Webber (aka Chief Thunderbird), to establish credibility in the minds of recruits and outside organiz Ilticlns. -

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’S Lost Colony of Roanoke

Where Have All the Indians Gone? Native American Eastern Seaboard Dispersal, Genealogy and DNA in Relation to Sir Walter Raleigh’s Lost Colony of Roanoke. Roberta Estes Copyright 2009, all rights reserved, submitted for publication [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract Within genealogy circles, family stories of Native American1 heritage exist in many families whose American ancestry is rooted in Colonial America and traverses Appalachia. The task of finding these ancestors either genealogically or using genetic genealogy is challenging. With the advent of DNA testing, surname and other special interest projects2, tools now exist to facilitate grouping participants in a way that allows one to view populations in historical fashions. This paper references and uses data from several of these public projects, but particularly the Melungeon, Lumbee, Waccamaw, North Carolina Roots and Lost Colony projects3. The Lumbee have long claimed descent from the Lost Colony via their oral history4. The Lumbee DNA Project shows significantly less Native American ancestry than would be expected with 96% European or African Y chromosomal DNA. The Melungeons, long held to be mixed European, African and Native show only one ancestral family with Native DNA5. Clearly more testing would be advantageous in all of these projects. This phenomenon is not limited to these groups, and has been reported by other researchers such as Bolnick (et al, 2006) where she reports finding in 16 Native American populations with northeast or southeast roots that 47% of the families who believe themselves to be full blooded or no less than 75% Native with no paternal European admixture find themselves carrying European or African y-line DNA. -

Catawba Militarism: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Overviews

CATAWBA MILITARISM: ETHNOHISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL OVERVIEWS by Charles L. Heath Abstract While many Indian societies in the Carolinas disappeared into the multi-colored fabric of Southern history before the mid-1700s, the Catawba Nation emerged battered, but ethnically viable, from the chaos of their colonial experience. Later, the Nation’s people managed to circumvent Removal in the 1830s and many of their descendants live in the traditional Catawba homeland today. To achieve this distinction, colonial and antebellum period Catawba leaders actively affected the cultural survival of their people by projecting a bellicose attitude and strategically promoting Catawba warriors as highly desired military auxiliaries, or “ethnic soldiers,” of South Carolina’s imperial and state militias after 1670. This paper focuses on Catawba militarism as an adaptive strategy and further elaborates on the effects of this adaptation on Catawba society, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While largely ethnohistorical in content, potential archaeological aspects of Catawba militarism are explored to suggest avenues for future research. American Indian societies in eastern North America responded to European imperialism in countless ways. Although some societies, such as the Powhatans and the Yamassees (Gleach 1997; Lee 1963), attempted to aggressively resist European hegemony by attacking their oppressors, resistance and adaptation took radically different forms in a colonial world oft referred to as a “tribal zone,” a “shatter zone,” or the “violent edge of empire” (Ethridge 2003; Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). Perhaps unique among their indigenous contemporaries in the Carolinas, the ethnically diverse peoples who came to form the “Catawba Nation” (see Davis and Riggs this volume) proactively sought to ensure their socio- political and cultural survival by strategically positioning themselves on the southern Anglo-American frontier as a militaristic society of “ethnic soldiers” (see Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). -

Conservation Chat History of Catawba River Presentation

SAVE LAND IN Perpetuity 17,000+ acres conserved across 7 counties 4 Focus Areas: • Clean Water • Wildlife Habitat • Local Farms • Connections to Nature Urbanization: Our disappearing green space 89,600 acres 985,600 acres 1,702,400 acres Example - Riverbend Protect from development on Johnson Creek Threat to Mountain Island Lake Critical drinking water supply Mecklenburg and Gaston Counties Working with developer and: City of Charlotte Charlotte Water Char-Meck Storm Water Gaston County Mt Holly Clean water Saving land protects water quality, quantity Silt, particulates, contamination Spills and fish kills Rusty Rozzelle Water Quality Program Manager, Mecklenburg County Member of the Catawba- Wateree Water Management Group Catawba - Wateree System 1200 feet above mean sea level Lake Rhodhiss Statesville Lake Hickory Lookout Shoals Lake James Hickory Morganton Marion Lake Norman Catawba Falls 2,350 feet above mean sea N Lincoln County level Mountain Island Lake • River Channel = 225 miles Gaston County Mecklenburg • Streams and Rivers = 3,285 miles County • Surface Area of Lakes = 79,895 acres (at full pond) N.C. • Basin Area = 4,750 square miles Lake Wylie • Population = + 2,000,000 S.C. Fishing Creek Reservoir Great Falls Reservoir Rocky Creek Lake Lake Wateree 147.5 feet above mean sea level History of the Catawba River The Catawba River was formed in the same time frame as the Appalachian Mountains about 220 millions years ago during the early Mesozoic – Late Triassic period Historical Inhabitants of the Catawba • 12,000 years ago – Paleo Indians inhabited the Americas migrating from northern Asia. • 6,000 years ago – Paleo Indians migrated south settling along the banks of the Catawba River obtaining much of their sustenance from the river. -

We've Wondered, Sponsored Two Previous Expeditions to Roanoke Speculated and Fantasized About the Fate of Sir Island

/'\ UNC Sea Grant June/July, 7984 ) ,, {l{HsT4IIHI'OII A Theodor de Bry dtawin! of a John White map Dare growing up to become an Indian princess. For 400 yearS, Or, the one about the Lumbee Indians being descendants of the colonists. Only a few people even know that Raleigh we've wondered, sponsored two previous expeditions to Roanoke speculated and fantasized about the fate of Sir Island. Or that those expeditions paved the way Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony. What happened to for the colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth. the people John White left behind? Historians This year, North Carolina begins a three-year and archaeologists have searched for clues. And celebration of Raleigh's voyages and of the people still the answers elude us. who attempted to settle here. Some people have filled in the gaps with fic- Coastwatc.tr looks at the history of the Raleigh tionalized.accounts of the colonists' fate. But ex- expeditions and the statewide efforts to com- perts take little stock in the legend of Virginia memorate America's beginnings. In celebration of the beginning an July, the tiny town of Manteo will undergo a transfor- Board of Commissioners made a commitment to ready the I mation. In the middle of its already crowded tourist town for the anniversary celebration, says Mayor John season, it will play host for America's 400th Anniversary. Wilson. Then, the town's waterfront was in a state of dis- Town officials can't even estimate how many thousands of repair. By contrast, at the turn of the century more than people will crowd the narrow streets. -

North Carolina Archaeology, Vol. 48

North Carolina Archaeology Volume 48 1999 1 North Carolina Archaeology (formerly Southern Indian Studies) Published jointly by The North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. 109 East Jones Street Raleigh, NC 27601-2807 and The Research Laboratories of Archaeology University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3120 R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Editor Officers of the North Carolina Archaeological Society President: Robert V. Graham, 2140 Woodland Ave., Burlington, NC 27215. Vice President: Michelle Vacca, 125 N. Elm Street, Statesville, NC 28677. Secretary: Linda Carnes-McNaughton, Historic Sites Section, N.C. Division of Archives and History, 4621 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699-4621. Treasurer: E. William Conen, 804 Kingswood Dr., Cary, NC 27513. Editor: R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr., Research Laboratories of Archaeology, CB 3120, Alumni Building, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3120. Associate Editor (Newsletter): Dee Nelms, Office of State Archaeology, N.C. Division of Archives and History, 4619 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699-4619. At-Large Members: Thomas Beaman, Department of Anthropology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858. Danny Bell, 903 Greenwood Road, Chapel Hill, NC 27514. Wayne Boyko, XVIII Airborne Corps and Fort Bragg, Public Works Business Center, Environmental Projects, Fort Bragg NC, 23807-5000 Jane Brown, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC 28723. Randy Daniel, Department of Anthropology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27858. Rick Langley, M.D., N.C. Department of Health and Human Services, Raleigh, NC. Information for Subscribers North Carolina Archaeology is published once a year in October. Subscription is by membership in the North Carolina Archaeological Society, Inc. -

These Hills, This Trail: Cherokee Outdoor Historical Drama and The

THESE HILLS, THIS TRAIL: CHEROKEE OUTDOOR HISTORICAL DRAMA AND THE POWER OF CHANGE/CHANGE OF POWER by CHARLES ADRON FARRIS III (Under the Direction of Marla Carlson and Jace Weaver) ABSTRACT This dissertation compares the historical development of the Cherokee Historical Association’s (CHA) Unto These Hills (1950) in Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Cherokee Heritage Center’s (CHC) The Trail of Tears (1968) in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears were originally commissioned to commemorate the survivability of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) and the Cherokee Nation (CN) in light of nineteenth- century Euramerican acts of deracination and transculturation. Kermit Hunter, a white southern American playwright, wrote both dramas to attract tourists to the locations of two of America’s greatest events. Hunter’s scripts are littered, however, with misleading historical narratives that tend to indulge Euramerican jingoistic sympathies rather than commemorate the Cherokees’ survivability. It wasn’t until 2006/1995 that the CHA in North Carolina and the CHC in Oklahoma proactively shelved Hunter’s dramas, replacing them with historically “accurate” and culturally sensitive versions. Since the initial shelving of Hunter’s scripts, Unto These Hills and The Trail of Tears have undergone substantial changes, almost on a yearly basis. Artists have worked to correct the romanticized notions of Cherokee-Euramerican history in the dramas, replacing problematic information with more accurate and culturally specific material. Such modification has been and continues to be a tricky endeavor: the process of improvement has triggered mixed reviews from touristic audiences and from within Cherokee communities themselves. -

US History- Sweeney

©Java Stitch Creations, 2015 Part 1: The Roanoke Colony-Background Information What is now known as the lost Roanoke Colony, was actually the third English attempt at colonizing the eastern shores of the United States. Following through with his family's thirst for exploration, Queen Elizabeth I of England granted Sir Walter Raleigh a royal charter in 1584. This charter gave him seven years to establish a settlement, and allowed him the power to explore, colonize and rnle, in return for one-fifth of all the gold and silver mined in the new lands. Raleigh immediately hired navigators Philip Amadas and Arthur Barlowe to head an expedition to the intended destination of the Chesapeake Bay area. This area was sought due to it being far from the Spanish-dominated Florida colonies, and it had milder weather than the more northern regions. In July of that year, they landed on Roanoke Island. They explored the area, made contact with Native Americans, and then sailed back to England to prove their findings to Sir Walter Raleigh. Also sailing from Roanoke were two members oflocal tribes of Native Americans, Manteo (son of a Croatoan) and Wanchese (a Roanoke). Amadas' and Barlowe's positive report, and Native American assistance, earned the blessing of Sir Walter Raleigh to establish a colony. In 1585, a second expedition of seven ships of colonists and supplies, were sent to Roanoke. The settlement was somewhat successful, however, they had poor relations with the local Native Americans and repeatedly experienced food shortages. Only a year after arriving, most of the colonists left. -

City Ends Mask Mandate Voters Elect

VOL. 123, ISSUE 27 | 50¢ Friday, April 9, 2021 ESTABLISHED 1898 City ends mask mandate Carolyn Ashford Boothe [email protected] GROVE — With the reduced risk level of COVID infections, the Grove City Council voted unanimously to allow the city’s mask mandate to expire at midnight on Tuesday, April 6. An attempt to also cancel the state of emergency resolution by Councilman Josh McElhaney was defeated on a 4-1 vote after a discussion by city staff including the city attorney to keep the ordinance in place in order to receive additional CARES funds as well as have it in place in case the number of COVID cases would spike again. Dr. Zackery Bechtol addressed the council surprisingly praising the actions of the city council. In November, Dr. Bechtol had testified against instituting a citywide mask mandate. Dr. Bechtol said that the “solidarity among groups in the city was an amazing thing to see…We got it just right. We are doing really good. The great job the council has done outweighs the small differences we had.” Dr. Bechtol also pointed out that Delaware County has one of the “highest vaccination rates in the state.” He pointed out that the Indian tribes have contributed to that effort by opening their facilities to non-Native Americans. The meeting on Tuesday was the last for outgoing council member Josh McElhaney since he chose not to run again. The mayor and each of the council members thanked him for his service and dedication to the city. In turn, McElhaney thanked his fellow members and also city manager Bill Keefer for helping mentor him.