Colonial Identifications for Native Americans in the Carolinas, 1540-1790

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geospatial Considerations Involving Historic General Land Office Maps and Late Prehistoric Bison Remains Near La Crosse, Wisconsin

Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology Volume 10 Article 11 2019 Geospatial Considerations Involving Historic General Land Office Maps and Late Prehistoric Bison Remains Near La Crosse, Wisconsin Andrew M. Saleh University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes Recommended Citation Saleh, Andrew M. (2019) "Geospatial Considerations Involving Historic General Land Office Maps and Late Prehistoric Bison Remains Near La Crosse, Wisconsin," Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology: Vol. 10 , Article 11. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/fieldnotes/vol10/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing Late Prehistoric Bison bison Remains near La Crosse, Wisconsin using Historic General Land Office Maps Andrew M. Saleh University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee, USA Abstract: This study used geographic information systems, pre- historic archaeological contexts, and historic General Land Of- fice (GLO) maps to conduct a pilot inter-site analysis involving La Crosse, Wisconsin area Oneota sites with reported Bison bi- son remains as of 2014. Scholars in and around Wisconsin con- tinually discuss the potential reasons why bison remains appear in late prehistoric contexts. This analysis continued that discus- sion with updated methods and vegetation data and provides a case study showing the strength of using historic GLO maps in conjunction with archaeological studies. This research suggests that creating your own maps in coordination with the GLO’s publicly available original surveyor data is more accurate than using the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ (DNR) vegetation polygon that cites the same data. -

MCJA Book Reviews Volume 39, 2014

OPEN ACCESS: MCJA Book Reviews Volume 39, 2014 Copyright © 2014 Midwest Archaeological Conference, Inc. All rights reserved. The Hoxie Farm Site Fortified Village: Late Fisher Phase Occupation and Fortification in South Chicago edited by Douglas K. Jackson and Thomas E. Emerson with contributions by Douglas K. Jackson. Thomas E. Emerson, Madeleine Evans, Ian Fricker, Kathryn C. Egan-Bruhy, Michael L. Hargrave, Terrance J. Martin, Kjersti E. Emerson, Eve A. Hargrave, Kris Hedman, Stephanie Daniels, Brenda Beck, Amanda Butler, Jennifer Howe, and Jean Nelson Research Report No. 27 Thomas E. Emerson, Ph.D. Principal Investigator and Survey Director Illinois State Archaeological Survey A Division of the Prairie Research Institute University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Investigations Conducted by: Illinois State Archaeological Survey University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Investigations Conducted Under the Auspices of: The State of Illinois Department of Transportation Brad H. Koldehoff Chief Archaeologist 2013 Contents List of Figures ...............................................................................................................................ix List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... xv Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... xix 1 Introduction Douglas K. Jackson ..................................................................................1 -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

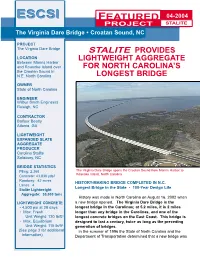

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine Andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2002 Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine andrea Paige White College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation White, andrea Paige, "Living on the Periphery: A Study of an Eighteenth-Century Yamasee Mission Community in Colonial St Augustine" (2002). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626354. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-whwd-r651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIVING ON THE PERIPHERY: A STUDY OF AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY YAMASEE MISSION COMMUNITY IN COLONIAL ST. AUGUSTINE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Andrea P. White 2002 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of aster of Arts Author Approved, November 2002 n / i i WJ m Norman Barka Carl Halbirt City Archaeologist, St. Augustine, FL Theodore Reinhart TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix ABSTRACT xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 2 Creolization Models in Historical Archaeology 4 Previous Archaeological Work on the Yamasee and Significance of La Punta 7 PROJECT METHODS 10 Historical Sources 10 Research Design and The City of St. -

Black-Indian Interaction in Spanish Florida

DOCUMEPT RESUME ED 320 845 SO 030 009 AUTHOR Landers, Jane TITLE Black/Indian Interaction in SpanishFlorida. PUB DATE 24 Mar 90 NOTE 25p.; Paper presented at the AnnualMeeting of the Organization of American Historians(Washington, DC, March 24, 1990). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) --Historical Materials (060) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian History; *Black History; *Colonial History (United States); Higher Education; *Indigenous Populations; Secondary Education; *Slavery; State History IDENTIFIERS *Florida ABSTRACT The history of the lives of non-white peoples in the United States largely has been neglected although the Spanish bureaucrats kept meticulous records of the Spanish Mission period in Florida. These records represent an important source for the cultural history of these groups and offer new perspectives on the tri-racial nature of frontier society. Africans as well as Indians played significant roles in Spain's settlement of the Americas. On arrival in Florida the Africans ran away from the," captors to Indian villages. The Spanish, perceiving an alliance of non-white groups, sought to separate them, and passed special legislation forbidding living or trading between the two groups. There were continuous episodes of violence by the Indians who resisted Spanish labor and tribute demands, efforts to convert them, and changes in their social practices. Villages were reduced to mission sites where they could more readily supply the Spaniards with food and labor. Indian and black surrogates were used to fight the English and helped build the massive stone fort at St. Augustine. The end of the Spanish Mission system came with the war of 1700, English forces from the Carolinas raided mission sites killing thousands of Indians and taking many into slavery. -

Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1939 Indian Place-Names in Mississippi. Lea Leslie Seale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Seale, Lea Leslie, "Indian Place-Names in Mississippi." (1939). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7812. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7812 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the master^ and doctorfs degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Library are available for inspection* Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author* Bibliographical references may be noted3 but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission# Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work# A library which borrows this thesis for vise by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions, LOUISIANA. STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 119-a INDIAN PLACE-NAMES IN MISSISSIPPI A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisian© State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Lea L # Seale M* A*, Louisiana State University* 1933 1 9 3 9 UMi Number: DP69190 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

APPENDIX A: Interview Guides for Participants

ABSTRACT DIAL, HEATHER KIMBERLY BARTON. Struggling for Voice in a Black and White World: Lumbee Indians’ Segregated Educational Experience in North Carolina. (Under the direction of Patricia L. Marshall, Ed.D. and Anna V. Wilson, Ph.D.) This study investigates the North Carolina Lumbee Indians’ segregated educational experience in North Carolina from 1885 to 1970. This oral history documents the experiences of the Lumbee Indians in the segregated Indian schools and adds their voices to the general discourse about Indian schools in our nation and to the history of education. The sample for this research included six members of the Lumbee community who experienced education in the segregated Indian schools in Hoke and Robeson Counties of southern North Carolina. My oral history research involved interviews with individuals who experienced the role of teachers, students, and administrators. A network selection sampling procedure was used to select participants. The main data sources were the participants’ oral educational histories. Limited archival research (e.g., board of education minutes) supports the final analysis. An analysis method for categorizing and classifying data was employed. The analysis method is similar to the constant comparative method of data analysis. Major findings show that the Lumbee students not only experienced a culturally supportive education, but also experienced a resource poor environment in the segregated Indian schools. Conversely, desegregation provided increased equity in educational resources and educational opportunities for the Lumbee students which unfortunately resulted in a loss of community, identity, and diminished teacher-student connection. Findings indicate the participants were aware of the role of segregation in the larger societal context. -

U Ni Ted States Departmen T of the Interior

Uni ted States Departmen t of the Interior BUREAU OF INDIAN AFFAIRS WASHINGTON, D.C. 20245 • IN REPLY REFER TO; MAR 281984. Tribal Government ;)ervices-F A MEMORANDUM To: A!:sistant Secretary - Indian Affairs From: DE!Puty Assistant Secretary - Indian Affairs (Operations) Subject: Rc!cornmendation and Summary of Evidence for Proposed Finding Against FE!deral Acknowledgment of the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc. Pursuant to 25 CFR 83. Recom mendatiol We recommend thut the United Lumbee Nation of North Carolina and America, Inc • (hereinafter "UGN") not be acknowledged as an Indian tribe entitled to a government to-government ]'elationship with the United States. We further recommend that a letter of the proposecl dc:!termination be forwarded to the ULN and other interested parties, • and that a notiC!e of the proposed finding that they do not exist as an Indian tribe be published in th4~ P,ederal Register. General Conclusions The ULN is a recently formed organization which did not exist prior to 1976. The organization WHS c!onceived, incorporated and promoted by one individual for personal interests and ,Ud not evolve from a tribal entity which existed on a substantially continuous bash from historical times until the present. The ULN has no relation to the Lumbees of the Robeson County area in North Carolina (hereinafter "Lumbees") historically soci.ally, genealogically, politically or organizationally. The use of the name "Lumbee" by Ule lILN appears to be an effort on the part of the founder, Malcolm L. Webber (aka Chief Thunderbird), to establish credibility in the minds of recruits and outside organiz Ilticlns. -

8 Grade Sample Social Studies Learning Plan

th 8 Grade Sample Social Studies Learning Plan Big Idea/ Topic American Indians & Exploration in Georgia Connecting Theme/Enduring Understanding: Location: The student will understand that location affects a society’s economy, culture, and development. Movement/Migration: The student will understand that the movement or migration of people and ideas affects all societies involved. Individuals, Groups, Institutions: The student will understand that the actions of individuals, groups, and/or institutions affect society through intended and unintended consequences. Essential Question: How were the lives of American Indians impacted by European exploration? Standard Alignment SS8H1 Evaluate the impact of European exploration and settlement on American Indians in Georgia. a. Describe the characteristics of American Indians living in Georgia at the time of European contact; to include culture, food, weapons/tools, and shelter. Connection to Literacy Standards for Social Studies and Social Studies Matrices L6-8RHSS5: Describe how a text presents information (e.g., sequentially, comparatively, casually). L6-8RHSS7: Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts L6-8WHST7: Conduct short research projects to answer a question (including a self-generated question), drawing on several sources and generating additional related, focused questions that allow for multiple avenues of exploration L6-8WHST4: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. L6-8WHST9: Draw evidence from informational texts to support analysis reflection, and research Information Processing Skills– 1 (compare similarities and differences) , 9 (construct charts and tables) Instructional Design *This lesson has a flexible timeline and will cross over several days. -

We've Wondered, Sponsored Two Previous Expeditions to Roanoke Speculated and Fantasized About the Fate of Sir Island

/'\ UNC Sea Grant June/July, 7984 ) ,, {l{HsT4IIHI'OII A Theodor de Bry dtawin! of a John White map Dare growing up to become an Indian princess. For 400 yearS, Or, the one about the Lumbee Indians being descendants of the colonists. Only a few people even know that Raleigh we've wondered, sponsored two previous expeditions to Roanoke speculated and fantasized about the fate of Sir Island. Or that those expeditions paved the way Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony. What happened to for the colonies at Jamestown and Plymouth. the people John White left behind? Historians This year, North Carolina begins a three-year and archaeologists have searched for clues. And celebration of Raleigh's voyages and of the people still the answers elude us. who attempted to settle here. Some people have filled in the gaps with fic- Coastwatc.tr looks at the history of the Raleigh tionalized.accounts of the colonists' fate. But ex- expeditions and the statewide efforts to com- perts take little stock in the legend of Virginia memorate America's beginnings. In celebration of the beginning an July, the tiny town of Manteo will undergo a transfor- Board of Commissioners made a commitment to ready the I mation. In the middle of its already crowded tourist town for the anniversary celebration, says Mayor John season, it will play host for America's 400th Anniversary. Wilson. Then, the town's waterfront was in a state of dis- Town officials can't even estimate how many thousands of repair. By contrast, at the turn of the century more than people will crowd the narrow streets. -

The Yamasee War: 1715 - 1717

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Archaeology Month Posters Institute of 10-2015 The aY masee War: 1715 - 1717 South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/archmonth_poster Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2015. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology--University of South Carolina. Archaeology Month Poster - The aY masee War: 1715 - 1717, 2015. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2015. http://artsandsciences.sc.edu/sciaa/ © 2015 by University of South Carolina, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Poster is brought to you by the Archaeology and Anthropology, South Carolina Institute of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archaeology Month Posters by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE YAMASEE WAR: 1715 - 1717 Thomas Nairne, “A map of South Carolina shewing the settlements of the English, French, & Indian nations from Charles Town to the River Missisipi [sic].” 1711. From Edward Crisp, “A compleat description of the province of Carolina in 3 parts.” Photo courtesy of Library of Congress 24th Annual South Carolina Archaeology Month October 2015 USC • South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology • 1321 Pendleton Street • Columbia S