Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cherokee Ethnogenesis in Southwestern North Carolina

The following chapter is from: The Archaeology of North Carolina: Three Archaeological Symposia Charles R. Ewen – Co-Editor Thomas R. Whyte – Co-Editor R. P. Stephen Davis, Jr. – Co-Editor North Carolina Archaeological Council Publication Number 30 2011 Available online at: http://www.rla.unc.edu/NCAC/Publications/NCAC30/index.html CHEROKEE ETHNOGENESIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NORTH CAROLINA Christopher B. Rodning Dozens of Cherokee towns dotted the river valleys of the Appalachian Summit province in southwestern North Carolina during the eighteenth century (Figure 16-1; Dickens 1967, 1978, 1979; Perdue 1998; Persico 1979; Shumate et al. 2005; Smith 1979). What developments led to the formation of these Cherokee towns? Of course, native people had been living in the Appalachian Summit for thousands of years, through the Paleoindian, Archaic, Woodland, and Mississippi periods (Dickens 1976; Keel 1976; Purrington 1983; Ward and Davis 1999). What are the archaeological correlates of Cherokee culture, when are they visible archaeologically, and what can archaeology contribute to knowledge of the origins and development of Cherokee culture in southwestern North Carolina? Archaeologists, myself included, have often focused on the characteristics of pottery and other artifacts as clues about the development of Cherokee culture, which is a valid approach, but not the only approach (Dickens 1978, 1979, 1986; Hally 1986; Riggs and Rodning 2002; Rodning 2008; Schroedl 1986a; Wilson and Rodning 2002). In this paper (see also Rodning 2009a, 2010a, 2011b), I focus on the development of Cherokee towns and townhouses. Given the significance of towns and town affiliations to Cherokee identity and landscape during the 1700s (Boulware 2011; Chambers 2010; Smith 1979), I suggest that tracing the development of towns and townhouses helps us understand Cherokee ethnogenesis, more generally. -

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

Late Mississippian Ceramic Production on St

LATE MISSISSIPPIAN CERAMIC PRODUCTION ON ST. CATHERINES ISLAND, GEORGIA Anna M. Semon A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Vincas P. Steponaitis C. Margaret Scarry R. P. Stephen Davis Anna Agbe-Davis John Scarry © 2019 Anna M. Semon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Anna M. Semon: Late Mississippian Ceramic Production on St. Catherines Island, Georgia (Under the direction of Vincas P. Steponaitis) This dissertation examines Late Mississippian pottery manufacturing on St. Catherines Island, Georgia. Data collected from five ceramic assemblages, three village and two mortuary sites, were used to characterize each ceramic assemblage and examine small-scale ceramic variations associated with learning and making pottery, which reflect pottery communities of practice. In addition, I examined pottery decorations to investigate social interactions at community and household levels. This dissertation is organized in six chapters. Chapter 1 provides the background, theoretical framework, and objectives of this research. Chapter 2 describes coastal Georgia’s culture history, with focus on the Mississippian period. Chapters 3 and 4 present the methods and results of this study. I use both ceramic typology and attribute analyses to explore ceramic variation. Chapter 3 provides details about the ceramic typology for each site. In addition, I examine the Mississippian surface treatments for each assemblage and identified ceramic changes between middle Irene (A.D. 1350–1450), late Irene (A.D. 1450–1580), and early Mission (A.D. 1580–1600) period. -

Further Investigations Into the King George

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22) Harry Gene Brignac Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Brignac Jr, Harry Gene, "Further investigations into the King George Island Mounds site (16LV22)" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2720. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2720 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE KING GEORGE ISLAND MOUNDS SITE (16LV22) A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of Geography and Anthropology By Harry Gene Brignac Jr. B.A. Louisiana State University, 2003 May, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to give thanks to God for surrounding me with the people in my life who have guided and supported me in this and all of my endeavors. I have to express my greatest appreciation to Dr. Rebecca Saunders for her professional guidance during this entire process, and for her inspiration and constant motivation for me to become the best archaeologist I can be. -

Pierce Mounds Complex an Ancient Capital in Northwest Florida

Pierce Mounds Complex An Ancient Capital in Northwest Florida Nancy Marie White Department of Anthropology University of South Florida, Tampa [email protected] Final Report to George J. Mahr, Apalachicola, Florida December 2013 ii ABSTRACT The Pierce site (8Fr14), near the mouth of the Apalachicola River in Franklin County, northwest Florida, was a major prehistoric mound center during the late Early and Middle Woodland (about A.D. 200-700) and Mississippian (about A.D. 1000-1500) periods. People lived there probably continuously during at least the last 2000 years (until right before the European invasion of Florida in the sixteenth century) and took advantage of the strategic location commanding the river and bay, as well as the abundant terrestrial and aquatic resources. Besides constructing several mounds for burial of the dead and probably support of important structures, native peoples left long midden (refuse) ridges of shells, animal bones, artifacts and blackened sandy soils, which built up a large and very significant archaeological site. Early Europeans and Americans who settled in the town of Apalachicola recognized the archaeological importance of Pierce and collected artifacts. But since the site and its spectacular findings were published by C.B. Moore in 1902, much information has been lost or misunderstood. Recent investigations by the University of South Florida were commissioned by the property owner to research and evaluate the significance of the site. There is evidence for an Early Woodland (Deptford) occupation and mound building, possibly as early as A.D. 200. Seven of the mounds form an oval, with the Middle Woodland burial mounds on the west side. -

Cultural Affiliation Statement for Buffalo National River

CULTURAL AFFILIATION STATEMENT BUFFALO NATIONAL RIVER, ARKANSAS Final Report Prepared by María Nieves Zedeño Nicholas Laluk Prepared for National Park Service Midwest Region Under Contract Agreement CA 1248-00-02 Task Agreement J6068050087 UAZ-176 Bureau of Applied Research In Anthropology The University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85711 June 1, 2008 Table of Contents and Figures Summary of Findings...........................................................................................................2 Chapter One: Study Overview.............................................................................................5 Chapter Two: Cultural History of Buffalo National River ................................................15 Chapter Three: Protohistoric Ethnic Groups......................................................................41 Chapter Four: The Aboriginal Group ................................................................................64 Chapter Five: Emigrant Tribes...........................................................................................93 References Cited ..............................................................................................................109 Selected Annotations .......................................................................................................137 Figure 1. Buffalo National River, Arkansas ........................................................................6 Figure 2. Sixteenth Century Polities and Ethnic Groups (after Sabo 2001) ......................47 -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998

GILA TOPMINNOW, Poeciliopsis occidentalis occidentalis, REVISED RECOVERY PLAN (Original Approval: March 15, 1984) Prepared by David A. Weedman Arizona Game and Fish Department Phoenix, Arizona for Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico December 1998 Approved: Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions required to recover and protect the species. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) prepares the plans, sometimes with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State and Federal Agencies, and others. Objectives are attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Time and costs provided for individual tasks are estimates only, and not to be taken as actual or budgeted expenditures. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor official positions or approval of any persons or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the Service. They represent the official position of the Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. ii Gila Topminnow Revised Recovery Plan December 1998 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Original preparation of the revised Gila topminnow Recovery Plan (1994) was done by Francisco J. Abarca 1, Brian E. Bagley, Dean A. Hendrickson 1 and Jeffrey R. Simms 1. That document was modified to this current version and the work conducted by those individuals is greatly appreciated and now acknowledged. -

Hohokam Legacy: Desert Canals (Pueblo Grande Museum Profiles No

Hohokam Legacy: Desert Canals (Pueblo Grande Museum Profiles No. 12) Jerry B. Howard Introduction Visitors to the Salt River Valley are often surprised to discover a fertile agricultural region flourishing in the arid Arizona desert. However, these modern agricultural achievements are not without precedent. From A.D. 600 to 1450, the prehistoric Hohokam constructed one of the largest and most sophisticated irrigation networks ever created using preindustrial technology. By A.D. 1200, hundreds of miles of these waterways created green paths winding out from the Salt and Gila Rivers, dotted with large platform mounds (see Illustrations 1 and 2). The remains of the ancient canals, lying beneath the streets of metropolitan Phoenix, are currently receiving greater attention from local archaeologists. We are only now beginning to understand the engineering, growth, and operation of the Hohokam irrigation systems. This information provides new insights into the Hohokam lifestyles and the organization of Hohokam society. Illustration 1. Extensive Canal System built by the Hohokam and others to divert water from the Gila River. (Source: Salt River Project) 1 www.waterhistory.org Hohokam Legacy: Desert Canals Illustration 2. Extensive Canal System built by the Hohokam to divert water from the Gila River. (Source: Southwest Parks and Monuments Association) Early Records of the Prehistoric Canals When the first explorers, trappers, and farmers entered the Salt River Valley, they were quick to note the impres- sive ruins left by the Hohokam. Villages containing platform mounds, elliptical ballcourts and trash mounds covered with broken ceramic pots and other artifacts existed throughout the valley. Stretching out from the river was a vast system of abandoned Hohokam canals that ran from site to site across the valley floor. -

Native Fish Restoration in Redrock Canyon

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Final Environmental Assessment Phoenix Area Office NATIVE FISH RESTORATION IN REDROCK CANYON U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest Santa Cruz County, Arizona June 2008 Bureau of Reclamation Finding of No Significant Impact U.S. Forest Service Finding of No Significant Impact Decision Notice INTRODUCTION In accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (Public Law 91-190, as amended), the Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation), as the lead Federal agency, and the Forest Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD), as cooperating agencies, have issued the attached final environmental assessment (EA) to disclose the potential environmental impacts resulting from construction of a fish barrier, removal of nonnative fishes with the piscicide antimycin A and/or rotenone, and restoration of native fishes and amphibians in Redrock Canyon on the Coronado National Forest (CNF). The Proposed Action is intended to improve the recovery status of federally listed fish and amphibians (Gila chub, Gila topminnow, Chiricahua leopard frog, and Sonora tiger salamander) and maintain a healthy native fishery in Redrock Canyon consistent with the CNF Plan and ongoing Endangered Species Act (ESA), Section 7(a)(2), consultation between Reclamation and the FWS. BACKGROUND The Proposed Action is part of a larger program being implemented by Reclamation to construct a series of fish barriers within the Gila River Basin to prevent the invasion of nonnative fishes into high-priority streams occupied by imperiled native fishes. This program is mandated by a FWS biological opinion on impacts of Central Arizona Project (CAP) water transfers to the Gila River Basin (FWS 2008a). -

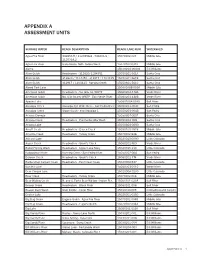

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Southwestern M O N U M E N

SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS MONTHLY REPORT OCTOBER - - - - 1938 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS OCTOBER, 1338, REPORT INDEX OPENING, by Superintendent Frank Pinkley, 27,1 CONDENSED GENERAL REPORT Travel ........... ,277 400 Flora, Fauna, and Natural 000 General. -278 Fhenomena. .280 100 Administrative . , . .278 500 Tse of Facilities by Public,280 200 Maintenance, Improvements, 600 Protection 281 and New Construction . .279 700 Archeology, Fist. ,Pre-Hist... 281 300 Activities Other .Agencies,279 900 Miscellaneous. ...... 282 RETORTS FPOM KEN IN THE FIE'D Arches .£34 Gran Ouivi'-a. ......... .294 Aztec Ruins ......... -.284 Hove:.weep 286 Bandelier .... ...... ..297 Mobile Unit .......... .336 Bandelier CCC ..... .299 Montezuma Jastle. ........ ,305 Bandelier Forestry. , .300 Natural Fridges ........ .320 Canyon de Chelly. ...... .318 • Navajo .312 Capulin Mountain. ...... ,319 pipe Spring 292 Casa Grande .......... -308 Saguaro ............ .237 Casa Grande Side Camp .... .310 Sunset Crater ......... .291 Chaco Canyon. ........ .302 Tumacacori. .......... .312 Chiricahua. ......... .295 -Yalnut Canyon ......... .301 Chiricahua CCC. ....... .296 White Sands .......... .283 El Morrc. .......... .315 Wupatki 289 HEADQUARTERS Aztec Ruins Visitor Statistics.333 Casa Grande Visitor Statistics. .331 Branch of Accounting. .... .339 Comparative Visitor Figures . .329 Branch of Education ..... .324 October Visitors to S.W.M 334 Branch of Maintenance .... :323 Personnel Notes 340 THE SUPPLEMENT Beaver Habitat at Bandelier, By W. B. McDcugall ..... .351 Geology Notes on the Montezuma Castle Region, by E..C. Alberts. .353 Geology Report on the Hovenweep National Monument, by C. N. Gould . .357 Moisture Retention of Cacti,'by David J.'Jones 353 Ruminations, by The Boss. '.'•'. .361 Supplemental Observations, from the- Field ........ .344 , SOUTHWESTERN MONUMENTS PERSONNEL HEADQUARTERS: National Park Service, Coolidge, Arizona. Frank Pinkley, Superintendent; Hugh M.