Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: Preservation and Recognition, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Survey of Prince House Woods, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, Roanoke Island, North Carolina

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF PRINCE HOUSE WOODS FORT RALEIGH NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE ROANOKE ISLAND, NORTH CAROLINA By: Nicholas M. Luccketti Submitted to: NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Southeast Archaeological Center 2035 East Paul Dirac Drive Johnson Building, Suite 120 Tallahassee, FL 23210 ARPA Permit # FORA 2006-001 SEAC Acc. # 2092 FORA Acc. # 88 January 2007 Submitted by: FIRST COLONY FOUNDATION 1501 Cole Mill Road Durham, NC 27705 ii MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Over the past 25 years, archaeological evidence related to the 16th-century Raleigh settlements on Roanoke Island in North Carolina has been found intermittently on the beach at the north end of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site between the Waterside Theater and the Prince House. These artifacts include an iron ax of 16th- century form, sherds of Iberian storage jar, and in the shallow water, an intact barrel buried and a hollowed out log which both radiocarbon dated to the 16th century. Furthermore, the exposed bluff in this area is subject to continual erosion, thus endangering any archaeological resources that may be present. Accordingly, the First Colony Foundation conducted a survey in October of 2006 to determine the potential for any significant archaeological features, strata, or artifact concentrations related to either the 1585 Lane Colony or the 1587 Lost Colony in the area between the edge of the bluff and the north end of the main parking lot. The 2006 fieldwork consisted of the excavation of test units along a transect that was located about 100’ behind the edge of the bluff. Additional test units were excavated along a foot path to the beach and in the dunes along the beach. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Roanoke Colony - Roanoke Chief] Die Furnemmesten der Inseln unde Statt / so Roanoac genannt (A Chief Lord of Roanoke) Stock#: 44430mp2 Map Maker: De Bry Date: 1590 Place: Frankfurt Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG Size: 9 x 12.5 inches Price: SOLD Description: The Chief / Lord of Roanoke -- Sir Walter Raleigh's Roanoke Colony -- Based on a painting by John White. Handsome image of a Roanoke Chief, detailing his manner of dress, hair, etc., with a few of the coatline of area of the Roanoke Colony in the background. In 1585, Governor John White, was part of a voyage from England to the Outer Banks of North Carolina under a plan of Sir Walter Raleigh to settle "Virginia." White was at Roanoke Island for about thirteen months before returning to England for more supplies. During this period he made a series of over seventy watercolor drawings of indigenous people, plants, and animals. The purpose of his drawings was to give those back home an accurate idea of the inhabitants and environment in the New World. The earliest Drawer Ref: Carolinas Stock#: 44430mp2 Page 1 of 4 Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] [Roanoke Colony - Roanoke Chief] Die Furnemmesten der Inseln unde Statt / so Roanoac genannt (A Chief Lord of Roanoke) images derived from White's original drawings were made in 1590, when Theodor De Bry made engravings from White's drawings to be printed in Thomas Hariot's account of the journey. -

Environmental Assessment of the Lower Cape Fear River System, 2013

Environmental Assessment of the Lower Cape Fear River System, 2013 By Michael A. Mallin, Matthew R. McIver and James F. Merritt August 2014 CMS Report No. 14-02 Center for Marine Science University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, N.C. 28409 Executive Summary Multiparameter water sampling for the Lower Cape Fear River Program (LCFRP) has been ongoing since June 1995. Scientists from the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s (UNCW) Aquatic Ecology Laboratory perform the sampling effort. The LCFRP currently encompasses 33 water sampling stations throughout the lower Cape Fear, Black, and Northeast Cape Fear River watersheds. The LCFRP sampling program includes physical, chemical, and biological water quality measurements and analyses of the benthic and epibenthic macroinvertebrate communities, and has in the past included assessment of the fish communities. Principal conclusions of the UNCW researchers conducting these analyses are presented below, with emphasis on water quality of the period January - December 2013. The opinions expressed are those of UNCW scientists and do not necessarily reflect viewpoints of individual contributors to the Lower Cape Fear River Program. The mainstem lower Cape Fear River is a 6th order stream characterized by periodically turbid water containing moderate to high levels of inorganic nutrients. It is fed by two large 5th order blackwater rivers (the Black and Northeast Cape Fear Rivers) that have low levels of turbidity, but highly colored water with less inorganic nutrient content than the mainstem. While nutrients are reasonably high in the river channels, major algal blooms have until recently been rare because light is attenuated by water color or turbidity, and flushing is usually high (Ensign et al. -

Ocanahowan and Recently Discovered Linguistic

2 OCANAHOWAN AND RECENTLY DISCOVERED LINGUISTIC FRAGMENTS FROM SOUTHERN VIRGINIA, C. 1650 Philip Barbour Ridgefield, Connecticut Published in: Papers of the 7th Algonquian Conference (1975) Ocanahowan (or Ocanahonan and other spellings) was the name of an Indian town or village, region or tribe, which was first reported in Captain John Smith's True Relation in 1608 and vanished from the records after Smith mentioned it for the last time 1624, until it turned up again in a few handwritten lines in the back of a book. Briefly, these lines cover half a page of a small quarto, and have been ascribed to the period from about 1650 to perhaps the end of the century, on the basis of style of writing. The page in question is the blank verso of the last page in a copy of Robert Johnson's Nova Britannia, published in London in 1604, now in the possession of a distinguished bibliophile of Williamsburg, Virginia. When I first heard about it, I was in London doing research and brushing up on the English language, Easter-time 1974, and Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., got in touch with me about "some rather meaningless annotations" in a small volume they had for sale. Very briefly put, for I shall return to the matter in a few minutes, I saw that the notes were of the time of the Jamestown colony and that they contained a few Powhatan words. Now that the volume has a new owner, and I have his permission to xerox and talk about it, I can explain why it aroused my interest to such an extent. -

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism

Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism By Matthew W. Horton A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Dr. Na’ilah Nasir, Chair Dr. Daniel Perlstein Dr. Keith Feldman Summer 2019 Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions Matthew W. Horton 2019 ABSTRACT Working Against Racism from White Subject Positions: White Anti-Racism, New Abolitionism & Intersectional Anti-White Irish Diasporic Nationalism by Matthew W. Horton Doctor of Philosophy in Education and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professor Na’ilah Nasir, Chair This dissertation is an intervention into Critical Whiteness Studies, an ‘additional movement’ to Ethnic Studies and Critical Race Theory. It systematically analyzes key contradictions in working against racism from a white subject positions under post-Civil Rights Movement liberal color-blind white hegemony and "Black Power" counter-hegemony through a critical assessment of two major competing projects in theory and practice: white anti-racism [Part 1] and New Abolitionism [Part 2]. I argue that while white anti-racism is eminently practical, its efforts to hegemonically rearticulate white are overly optimistic, tend toward renaturalizing whiteness, and are problematically dependent on collaboration with people of color. I further argue that while New Abolitionism has popularized and advanced an alternative approach to whiteness which understands whiteness as ‘nothing but oppressive and false’ and seeks to ‘abolish the white race’, its ultimately class-centered conceptualization of race and idealization of militant nonconformity has failed to realize effective practice. -

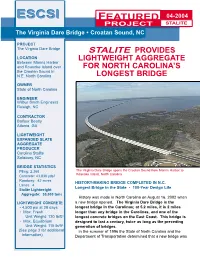

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

A Case Study of Carolina Bays and Ditched Streams at Risk Under the Proposed WOTUS Definition

CAPE FEAR RIVER WATERSHED: A Case Study of Carolina Bays and Ditched Streams at Risk under the Proposed WOTUS Definition The Cape Fear River. Photo by Kemp Burdette The Cape Fear River Basin is North Carolina’s largest watershed, with an area of over 9,000 square miles. Major tributaries include the Deep River, the Haw River, the Northeast Cape Fear River, the Black River, and the South River. These rivers converge to form a thirty-mile-long estuary before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Fear.1 The Cape Fear supplies water to some of the fastest growing counties in the United States;2 roughly one in five North Carolinians gets their drinking water from the Cape Fear, including residents of Greensboro, Fayetteville, and Wilmington.3 The Cape Fear Basin is a popular watershed for a variety of recreation activities. State parks along the river include Haw River State Park, Raven Rock State Park, and Carolina Beach State Park. The faster-flowing water of the upper basin is popular with paddlers, as are the slow meandering blackwater rivers and streams of the lower Cape Fear and estuary. Fishing is very popular; the Cape Fear supports a number of freshwater species, saltwater species, and even anadromous (migratory) species like the endangered sturgeon, striped bass, and shad. Cape Fear River Watershed: Case Study Page 2 of 8 The Cape Fear is North Carolina’s most ecologically diverse watershed; the Lower Cape Fear is notable because it is part of a biodiversity “hotspot,” recording the largest degree of biodiversity on the eastern seaboard of the United States. -

Who Is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean

Social Education 81(1), pp 37–42 ©2017 National Council for the Social Studies Teaching and Learning African American History Who is Afro-Latin@? Examining the Social Construction of Race and Négritude in Latin America and the Caribbean Christopher L. Busey and Bárbara C. Cruz By the 1930s the négritude ideological movement, which fostered a pride and conscious- The rejection of négritude is not a ness of African heritage, gained prominence and acceptance among black intellectuals phenomenon unique to the Dominican in Europe, Africa, and the Americas. While embraced by many, some of African Republic, as many Latin American coun- descent rejected the philosophy, despite evident historical and cultural markers. Such tries and their respective social and polit- was the case of Rafael Trujillo, who had assumed power in the Dominican Republic ical institutions grapple with issues of in 1930. Trujillo, a dark-skinned Dominican whose grandmother was Haitian, used race and racism.5 For example, in Mexico, light-colored pancake make-up to appear whiter. He literally had his family history African descended Mexicans are socially rewritten and “whitewashed,” once he took power of the island nation. Beyond efforts isolated and negatively depicted in main- to alter his personal appearance and recast his own history, Trujillo also took extreme stream media, while socio-politically, for measures to erase blackness in Dominican society during his 31 years of dictatorial the first time in the country’s history the rule. On a national level, Trujillo promoted -

Cape Fear River Blueprint

Lower Cape Fear River Blueprint Since 1982, the North Carolina Coastal Federation has worked with residents and visitors of North Carolina to protect and restore the coast, including participating in many issues and projects within the Cape Fear region. The Lower Cape Fear River provides critical coastal and riverine habitat, storm and flood protection and commercial and recreational fishery resources. It is also a popular recreational destination and an economic driver for the state’s southeastern region, and it embodies a rich historic and cultural heritage. The river also serves as an important source of drinking water for many coastal communities, including the City of Wilmington. Today, the lower river needs improved environmental safeguards, a clear vision for compatible and sustainable economic development. Further, effective leadership is needed to address existing issues of pollution and habitat loss and prevent projects that threaten the health of the community and the river. The Lower Cape Fear River is continually affected by both local and upstream actions. The continued degradation of these essential functions threatens the well-being of all within the community. The Coastal Federation continues to address these issues by actively engaging with local governments, state and federal agencies and other entities. Our board of directors recognizes these needs and adopted the following goals as part of a three-year, organizationwide initiative: Advocate for compatible industrial development in the coastal zone; Restore coastal habitats and protect water quality; Improve our economy through coastal restoration. The Lower Cape Fear River Blueprint (The Blueprint) is a collaborative effort to focus on the river’s estuarine and riverine natural resources. -

Supplemental Article to Where Is the Lost Colony?

Challenges to living by the sea A supplement to the serial story, Where is The Lost Colony? written by Sandy Semans, editor, Outer Banks Sentinel The thin ribbon of sand that forms the chain of islands known as the Outer Banks is bounded on the east by the Atlantic Ocean and on the west by the sounds. The shapes of the islands and the inlets that run between them continue to be altered by hurricanes, nor’easters and other weather events. Inlets that often proved to be moving targets created access to the ocean and the sounds. Inlets were formed and then later filled with sand and disappeared. Maps of the coastline show many places named “New Inlet,” although currently there is no inlet there. The one exception has been Ocracoke Inlet between Ocracoke and Portsmouth islands. Marine geologists estimate that the existing inlet — with some minor changes — has been in place for at least 2500 years. During the English exploration of the 1500’s, most likely the ships came through this inlet, making it a long sail to Roanoke Island. At that time, there was a small shallow inlet between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands, but the shallow inlet probably was avoided for fear of going aground. By the early 1700s, this inlet had filled in, and the two became just one long island. But in 1846, a hurricane created two major inlets. One, now called Oregon Inlet, sliced through the sand, leaving today’s Pea Island to the south and Bodie Island to the north. And a second inlet, now known as Hatteras Inlet, once again separated Hatteras Island from Ocracoke Island. -

Coral Reefs, Unintentionally Delivering Bermuda’S E-Mail: [email protected] fi Rst Colonists

Introduction to Bermuda: Geology, Oceanography and Climate 1 0 Kathryn A. Coates , James W. Fourqurean , W. Judson Kenworthy , Alan Logan , Sarah A. Manuel , and Struan R. Smith Geographic Location and Setting Located at 32.4°N and 64.8°W, Bermuda lies in the northwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is isolated by distance, deep Bermuda is a subtropical island group in the western North water and major ocean currents from North America, sitting Atlantic (Fig. 10.1a ). A peripheral annular reef tract surrounds 1,060 km ESE from Cape Hatteras, and 1,330 km NE from the islands forming a mostly submerged 26 by 52 km ellipse the Bahamas. Bermuda is one of nine ecoregions in the at the seaward rim of the eroded platform (the Bermuda Tropical Northwestern Atlantic (TNA) province (Spalding Platform) of an extinct Meso-Cenozoic volcanic peak et al. 2007 ) . (Fig. 10.1b ). The reef tract and the Bermuda islands enclose Bermuda’s national waters include pelagic environments a relatively shallow central lagoon so that Bermuda is atoll- and deep seamounts, in addition to the Bermuda Platform. like. The islands lie to the southeast and are primarily derived The Bermuda Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends from sand dune formations. The extinct volcano is drowned approx. 370 km (200 nautical miles) from the coastline of the and covered by a thin (15–100 m), primarily carbonate, cap islands. Within the EEZ, the Territorial Sea extends ~22 km (Vogt and Jung 2007 ; Prognon et al. 2011 ) . This cap is very (12 nautical miles) and the Contiguous Zone ~44.5 km (24 complex, consisting of several sets of carbonate dunes (aeo- nautical miles) from the same baseline, both also extending lianites) and paleosols laid down in the last million years well beyond the Bermuda Platform.