The North End of Roanoke Island in the 17Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 245/Monday, December 21, 2020/Proposed Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 245 / Monday, December 21, 2020 / Proposed Rules 83001 FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE otherwise sensitive information COMMISSION submitted voluntarily by the sender will National Oceanic and Atmospheric be publicly accessible. NMFS will 47 CFR Part 73 Administration accept anonymous comments (enter ‘‘N/A’’ in the required fields if you wish [MB Docket No. 19–310 and 17–105; Report 50 CFR Part 218 to remain anonymous). Attachments to No. 3164; FRS 17301] [Docket No. 201207–0329] electronic comments will be accepted in Microsoft Word, Excel, or Adobe PDF Petition for Reconsideration of Action RIN 0648–BJ90 file formats only. in Proceedings FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Takes of Marine Mammals Incidental to Leah Davis, Office of Protected Specified Activities; Taking Marine AGENCY: Federal Communications Resources, NMFS, (301) 427–8401. Mammals Incidental to U.S. Navy Commission. Construction at Naval Station Norfolk SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: ACTION: Petition for Reconsideration. in Norfolk, Virginia Availability AGENCY: National Marine Fisheries A copy of the Navy’s application and SUMMARY: Petition for Reconsideration Service (NMFS), National Oceanic and any supporting documents, as well as a (Petition) has been filed in the Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), list of the references cited in this Commission’s proceeding by Rachel Commerce. document, may be obtained online at: Stilwell and Samantha Gutierrez, on ACTION: Proposed rule; request for https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/ behalf of REC Networks, musicFIRST comments. incidental-take-authorization-us-navy- Coalition and Future of Music Coalition. construction-naval-station-norfolk- SUMMARY: NMFS has received a request norfolk-virginia. In case of problems DATES: Oppositions to the Petition must from the U.S. -

Environmental Assessment of the Lower Cape Fear River System, 2013

Environmental Assessment of the Lower Cape Fear River System, 2013 By Michael A. Mallin, Matthew R. McIver and James F. Merritt August 2014 CMS Report No. 14-02 Center for Marine Science University of North Carolina Wilmington Wilmington, N.C. 28409 Executive Summary Multiparameter water sampling for the Lower Cape Fear River Program (LCFRP) has been ongoing since June 1995. Scientists from the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s (UNCW) Aquatic Ecology Laboratory perform the sampling effort. The LCFRP currently encompasses 33 water sampling stations throughout the lower Cape Fear, Black, and Northeast Cape Fear River watersheds. The LCFRP sampling program includes physical, chemical, and biological water quality measurements and analyses of the benthic and epibenthic macroinvertebrate communities, and has in the past included assessment of the fish communities. Principal conclusions of the UNCW researchers conducting these analyses are presented below, with emphasis on water quality of the period January - December 2013. The opinions expressed are those of UNCW scientists and do not necessarily reflect viewpoints of individual contributors to the Lower Cape Fear River Program. The mainstem lower Cape Fear River is a 6th order stream characterized by periodically turbid water containing moderate to high levels of inorganic nutrients. It is fed by two large 5th order blackwater rivers (the Black and Northeast Cape Fear Rivers) that have low levels of turbidity, but highly colored water with less inorganic nutrient content than the mainstem. While nutrients are reasonably high in the river channels, major algal blooms have until recently been rare because light is attenuated by water color or turbidity, and flushing is usually high (Ensign et al. -

Birth of a Colony North Carolina Guide for Educators Act IV—A New Voyage to Carolina, 1650–1710

Birth of a Colony North Carolina Guide for Educators Act IV—A New Voyage to Carolina, 1650–1710 Birth of a Colony Guide for Educators Birth of a Colony explores the history of North Carolina from the time of European exploration through the Tuscarora War. Presented in five acts, the video combines primary sources and expert commentary to bring this period of our history to life. Use this study guide to enhance students’ understanding of the ideas and information presented in the video. The guide is organized according to five acts. Included for each act are a synopsis, a vocabulary list, discussion questions, and lesson plans. Going over the vocabulary with students before watching the video will help them better understand the film’s content. Discussion questions will encourage students to think critically about what they have viewed. Lesson plans extend the subject matter, providing more information or opportunity for reflection. The lesson plans follow the new Standard Course of Study framework that takes effect with the 2012–2013 school year. With some adjustments, most of the questions and activities can be adapted for the viewing audience. Birth of a Colony was developed by the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, in collaboration with UNC-TV and Horizon Productions. More resources are available at the website http://www.unctv.org/birthofacolony/index.php. 2 Act IV—A New Voyage to Carolina, 1650–1710 Act IV of Birth of a Colony is divided into three parts. The first part explores the development of permanent English settlements in North Carolina. For nearly 70 years after the mysterious disappearance of the Lost Colony, North Carolina remained void of European settlement. -

Ocanahowan and Recently Discovered Linguistic

2 OCANAHOWAN AND RECENTLY DISCOVERED LINGUISTIC FRAGMENTS FROM SOUTHERN VIRGINIA, C. 1650 Philip Barbour Ridgefield, Connecticut Published in: Papers of the 7th Algonquian Conference (1975) Ocanahowan (or Ocanahonan and other spellings) was the name of an Indian town or village, region or tribe, which was first reported in Captain John Smith's True Relation in 1608 and vanished from the records after Smith mentioned it for the last time 1624, until it turned up again in a few handwritten lines in the back of a book. Briefly, these lines cover half a page of a small quarto, and have been ascribed to the period from about 1650 to perhaps the end of the century, on the basis of style of writing. The page in question is the blank verso of the last page in a copy of Robert Johnson's Nova Britannia, published in London in 1604, now in the possession of a distinguished bibliophile of Williamsburg, Virginia. When I first heard about it, I was in London doing research and brushing up on the English language, Easter-time 1974, and Bernard Quaritch, Ltd., got in touch with me about "some rather meaningless annotations" in a small volume they had for sale. Very briefly put, for I shall return to the matter in a few minutes, I saw that the notes were of the time of the Jamestown colony and that they contained a few Powhatan words. Now that the volume has a new owner, and I have his permission to xerox and talk about it, I can explain why it aroused my interest to such an extent. -

Oregon Inlet Opened in 1846 As Water Rushed from the Sound to the Ocean

Oregon Inlet opened in 1846, when a big hurricane along the Outer Banks caused water to rush from the sound to the ocean. Since that time, the inlet has migrated steadily south at a rate of around 100 feet per year. A good measure of the inlet’s journey is the Bodie Island Lighthouse, which once stood at the margin of the inlet but is now 3 miles away. In 1962, the Bonner Bridge replaced the ferry that shuttled people and cars across Oregon Inlet. Construction of the bridge, with its high fixed-span, instantly stopped the long history if inlet migration. But sand continued to pour into the inlet from the north, the driving force behind the inlet’s southerly migration, creating ever-expanding navigation and dredging problems. After 40 years, the Bonner Bridge is rapidly deteriorating and two possible replacement alternatives are being evaluated: A bridge immediately parallel to the current bridge and a 17 mile-long bridge that would extend into Pamlico Sound, run along the backside of Pea Island and connect to Hatters Island at Rodanthe. The initial cost of constructing the Pamlico Sound Bridge is much higher than that of the Parallel Bridge. But the overall long-term costs of a Parallel Bridge greatly exceed those of the Pamlico Sound Bridge. This is because the Parallel Bridge requires the continued protection and maintenance of State Highway 12 on Pea Island. Over time, as the shoreline erodes back in response to a rising sea level, the cost of stabilizing Pea Island will become higher. Construction impacts to wetlands and sea grass beds are essentially the same for each bridge. -

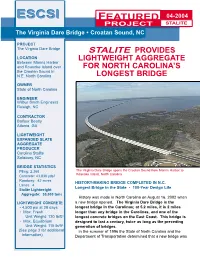

FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT the MONTH STALITE the Virginia Dare Bridge ¥ Croatan Sound, NC

ESCSIESCSI FEATURED 04-2004 OFPROJECT THE MONTH STALITE The Virginia Dare Bridge • Croatan Sound, NC PROJECT The Virginia Dare Bridge STALITE PROVIDES LOCATION LIGHTWEIGHT AGGREGATE Between Manns Harbor and Roanoke Island over FOR NORTH CAROLINA’S the Croatan Sound in N.E. North Carolina LONGEST BRIDGE OWNER State of North Carolina ENGINEER Wilbur Smith Engineers Raleigh, NC CONTRACTOR Balfour Beatty Atlanta, GA LIGHTWEIGHT EXPANDED SLATE AGGREGATE PRODUCER Carolina Stalite Salisbury, NC BRIDGE STATISTICS Piling: 2,368 The Virginia Dare Bridge spans the Croatan Sound from Manns Harbor to Roanoke Island, North Carolina Concrete: 43,830 yds3 Roadway: 42 acres HISTORY-MAKING BRIDGE COMPLETED IN N.C. Lanes: 4 Longest Bridge in the State • 100-Year Design Life Stalite Lightweight Aggregate: 30,000 tons History was made in North Carolina on August 16, 2002 when LIGHTWEIGHT CONCRETE a new bridge opened. The Virginia Dare Bridge is the • 4,500 psi at 28 days longest bridge in the Carolinas; at 5.2 miles, it is 2 miles • Max. Fresh longer than any bridge in the Carolinas, and one of the Unit Weight: 120 lb/ft3 longest concrete bridges on the East Coast. This bridge is • Max. Equilibrium designed to last a century, twice as long as the preceding Unit Weight: 115 lb/ft3 generation of bridges. (See page 3 for additional In the summer of 1996 the State of North Carolina and the information) Department of Transportation determined that a new bridge was ESCSI The Virginia Dare Bridge 2 required to replace the present William B. Umstead Bridge con- necting the Dare County main- land with the hurricane-prone East Coast. -

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions

The Archaeology of Virginia's Long Seventeenth Century, 1550-1720: Previous Research and Future Directions Dennis J. Pogue Time Line x 1561-66: Spanish expeditions from Havana and La Florida explore the Chesapeake Bay in search of trade routes to the west and to scout potential sites for settlement. x 1570: Jesuit priests establish the Ajacan mission on the York River in an attempt to Christianize the native Indians; the venture fails the next year when the priests are killed by the natives. x 1607: The English establish their first permanent settlement in Virginia when 104 colonists disembark at Jamestown Island and erect James Fort. x 1607-08: John Smith and his crew explore the Chesapeake Bay and its major tributaries by boat; the Englishmen record the locations of the Indian settlements they pass. x 1609-14: Colonists and the Powhatan Indians engage in a series of armed conflicts as the natives attempt to protect their rights to the land. x 1614: English settlers begin to cultivate tobacco, which becomes the primary source of wealth for the colony for the next 200 years. x 1617-22: Twenty-three "particular plantations," or subsidiary corporations controlled by stock holders, are created as part of an attempt to encourage immigration and the spread of settlement beyond Jamestown. x 1619: The first enslaved Africans are introduced to Virginia; the first representative legislative assembly is formed. x 1622: 200,000 pounds of tobacco are shipped out of Virginia; the homes of 1500 settlers spread for 50 miles along the James River; in response to the pressures of continued immigration of Englishmen, the Powhatan Indians attack and kill several hundred settlers in a series of coordinated attacks. -

A Case Study of Carolina Bays and Ditched Streams at Risk Under the Proposed WOTUS Definition

CAPE FEAR RIVER WATERSHED: A Case Study of Carolina Bays and Ditched Streams at Risk under the Proposed WOTUS Definition The Cape Fear River. Photo by Kemp Burdette The Cape Fear River Basin is North Carolina’s largest watershed, with an area of over 9,000 square miles. Major tributaries include the Deep River, the Haw River, the Northeast Cape Fear River, the Black River, and the South River. These rivers converge to form a thirty-mile-long estuary before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean at Cape Fear.1 The Cape Fear supplies water to some of the fastest growing counties in the United States;2 roughly one in five North Carolinians gets their drinking water from the Cape Fear, including residents of Greensboro, Fayetteville, and Wilmington.3 The Cape Fear Basin is a popular watershed for a variety of recreation activities. State parks along the river include Haw River State Park, Raven Rock State Park, and Carolina Beach State Park. The faster-flowing water of the upper basin is popular with paddlers, as are the slow meandering blackwater rivers and streams of the lower Cape Fear and estuary. Fishing is very popular; the Cape Fear supports a number of freshwater species, saltwater species, and even anadromous (migratory) species like the endangered sturgeon, striped bass, and shad. Cape Fear River Watershed: Case Study Page 2 of 8 The Cape Fear is North Carolina’s most ecologically diverse watershed; the Lower Cape Fear is notable because it is part of a biodiversity “hotspot,” recording the largest degree of biodiversity on the eastern seaboard of the United States. -

Pocahontas's Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty

言語・地域文化研究 第 ₂6 号 2020 103 Pocahontas’s Two Rescues and Her Fluid Loyalty Hiroyuki Tsukada ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ 塚田 浩幸 要 旨 ポカホンタスは、二度、ジョン・スミスの命を救った。一度目は有名な助命で、1607 年 12 月、インディアンの首長パウハタンによる処刑の寸前に、ポカホンタスが捕虜スミ スに自分の体をなげうって助命をした。これは、スミスの死と生まれ変わりを象徴的に 意味し、入植者をインディアンの世界に迎え入れる儀式で、ポカホンタスはスミスを救 うというあらかじめ決められた役割を担った。この一度目の助命の真偽については長ら く論争が行なわれてきたが、スミスが 1608 年 6 月の報告書簡でポカホンタスを「比類な き人物」と高く評価できたという事実は、助命が実際に起きたことを示している。その 6 月の時点で、スミスは助命の他に、取引や物資の提供と人質解放交渉の場面でポカホ ンタスと会う機会を持っていたが、それらの場面においては、スミスが「比類なき人物」 と評価することができるほどの行動をポカホンタスがとっていなかったからである。そ して、スミスがその報告書簡でポカホンタスを紹介したのは、入植事業の宣伝のために インディアンとの平和友好をアピールするねらいがあった。つまり、スミスに批判的な 研究者が主張するように、スミスがポカホンタスの人気にあやかって自分の名声をあげ るために助命を捏造したのではなく、助命に感銘を受けたスミスがポカホンタスの人気 を作り上げたといえるのである。 パウハタンは、一度目の助命でポカホンタスをインディアンと入植者の平和友好のシ ンボルとして仕立て上げ、その後の平和的な外交の場面にもポカホンタスを同行させて いた。しかしながら、二度目の助命は、パウハタンの外交方針に逆らって、ポカホンタ ス自身の意思によって行なわれた。1609 年 1 月、インディアンと入植者の関係が悪化す るなか、パウハタンがスミスを本当に襲おうとしているところをポカホンタスがスミス に密告して救った。この二つの助命のあいだの期間、ポカホンタスは入植者と頻繁に会 うなかで理解を深め、パウハタン連合のインディアンとしての忠誠心に揺らぎを生じさ せていたのである。つまり、ポカホンタスは、単なるパウハタンの遣いとしての平和友 好のシンボルであることをやめ、自らを平和友好の使者として確立させるに至ったので ある。 本稿の著作権は著者が保持し、クリエイティブ・コモンズ表示 4.0 国際ライセンス(CC-BY)下に提供します。 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ja 104 論文 ポカホンタスの二つの助命と忠誠心の揺らぎ (塚田 浩幸) Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. A special relationship between Pocahontas and John Smith 3. Refutation of all existing theories 4. Demonstration of the veracity of the rescue 5. Conclusion 1. Introduction Pocahontas saved John Smith twice. The frst instance came in December 1607, when she symbolically ofered her own head to save Smith’s -

The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1992 "This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish Tudor and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice Meaghan Noelle Duff College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Duff, Meaghan Noelle, ""This Famous Island in the Virginia Sea": The Influence of the Irish udorT and Stuart Plantation Experiences in the Evolution of American Colonial Theory and Practice" (1992). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625771. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-kvrp-3b47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS FAMOUS ISLAND IN THE VIRGINIA SEA": THE INFLUENCE OF IRISH TUDOR AND STUART PLANTATION EXPERIENCES ON THE EVOLUTION OF AMERICAN COLONIAL THEORY AND PRACTICE A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY MEAGHAN N. DUFF MAY, 1992 APPROVAL SHEET THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS AGHAN N APPROVED, MAY 1992 '''7 ^ ^ THADDEUS W. TATE A m iJI________ JAMES AXTELL CHANDOS M. -

MAAC 2012 Preliminary Program Virginia Beach, VA March 23-25 8

MAAC 2012 Preliminary Program March 23-25 Virginia Beach, VA Friday Morning, March 23 Track A Session 1: Archaeology of the 20th Century: Addressing the Recent Past Organized by Richard L. Geurcin (USDA Forest Service) 8:30 AM 8:50 AM Towards an Understanding of the 20th Century Guercin, Richard J. (USDA Forest Service) 8:50 AM 9:10 AM Finding the 20th Century Inside the 18th: Archaeology at Ogborne, Jennifer (College of William and the Menokin Site Mary/DATA Investigations, LLC) 9:10 AM 9:30 AM Deterioration and Rehabilitation of the Infrastructure on O Palus, Matthew (The Ottery Group) and P Streets in the Georgetown Neighborhood of Washington, D.C. 9:30 AM 9:50 AM The Missing Pieces of the 20th Century: Excavations at the Moore, Elizabeth A. (Virginia Museum of Natural Gravely House History) 9:50 AM 10:05 AM Break 10:05 AM 10:25 AM An Early Twentieth Century Ceramic Assemblage from a Garrow, Patrick H. (Cultural Resource Analysts, Burned House in Northern Georgia Inc.) 10:25 AM 10:45 AM From Timber to Town to Timber Again: The Story of the Barile , Kerri S. (Dovetail Cultural Resource Kress Box Factory in Brunswick, Virginia Group) and Kerry S. González (Dovetail Cultural Resource Group) 10:45 AM 11:05 AM A steppingstone of civilization”: The Hojack Swing Bridge Somerville, Kyle (University at Buffalo) and and Structures of Power in Monroe County, Western New Christopher Barton (Temple University) York State 11:05 AM 11:25 AM In Harm’s Way: The Hazard’s of Archaeological Field Madden, Michael (USDA Forest Service) Work Involving 20th Century Military Sites 11:25 AM 11:45 AM Saving the Present for the Future’s Past: Documenting Orr, David G. -

Coral Reefs, Unintentionally Delivering Bermuda’S E-Mail: [email protected] fi Rst Colonists

Introduction to Bermuda: Geology, Oceanography and Climate 1 0 Kathryn A. Coates , James W. Fourqurean , W. Judson Kenworthy , Alan Logan , Sarah A. Manuel , and Struan R. Smith Geographic Location and Setting Located at 32.4°N and 64.8°W, Bermuda lies in the northwest of the Sargasso Sea. It is isolated by distance, deep Bermuda is a subtropical island group in the western North water and major ocean currents from North America, sitting Atlantic (Fig. 10.1a ). A peripheral annular reef tract surrounds 1,060 km ESE from Cape Hatteras, and 1,330 km NE from the islands forming a mostly submerged 26 by 52 km ellipse the Bahamas. Bermuda is one of nine ecoregions in the at the seaward rim of the eroded platform (the Bermuda Tropical Northwestern Atlantic (TNA) province (Spalding Platform) of an extinct Meso-Cenozoic volcanic peak et al. 2007 ) . (Fig. 10.1b ). The reef tract and the Bermuda islands enclose Bermuda’s national waters include pelagic environments a relatively shallow central lagoon so that Bermuda is atoll- and deep seamounts, in addition to the Bermuda Platform. like. The islands lie to the southeast and are primarily derived The Bermuda Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extends from sand dune formations. The extinct volcano is drowned approx. 370 km (200 nautical miles) from the coastline of the and covered by a thin (15–100 m), primarily carbonate, cap islands. Within the EEZ, the Territorial Sea extends ~22 km (Vogt and Jung 2007 ; Prognon et al. 2011 ) . This cap is very (12 nautical miles) and the Contiguous Zone ~44.5 km (24 complex, consisting of several sets of carbonate dunes (aeo- nautical miles) from the same baseline, both also extending lianites) and paleosols laid down in the last million years well beyond the Bermuda Platform.