Rascheldruck 2013 Englisch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hopwood Newsletter Vol

Hopwood Newsletter Vol. LXXVIX, 1 lsa.umich.edu/hopwood January 2018 HOPWOOD The Hopwood Newsletter is published electronically twice a year, in January and July. It lists the publications and activities of winners of the Summer Hopwood Contest, Hopwood Underclassmen Contest, Graduate and Undergraduate Hopwood Contest, and the Hopwood Award Theodore Roethke Prize. Sad as I am to be leaving, I’m delighted to announce my replacement as the Hopwood Awards Program Assistant Director. Hannah is a Hopwood winner herself in Undergraduate Poetry in 2009. Her email address is [email protected], so you should address future newsletter items to her. Hannah Ensor is from Michigan and received her MFA in poetry at the University of Arizona. She joins the Hopwood Program from the University of Arizona Poetry Center, where she was the literary director, overseeing the Poetry Center’s reading & lecture series, classes & workshops program, student contests, and summer residency program. Hannah is a also co-editor of textsound.org (with poet and Michigan alumna Laura Wetherington), a contributing poetry editor for DIAGRAM, and has served as president of the board of directors of Casa Libre en la Solana, a literary arts nonprofit in Tucson, Arizona. Her first book of poetry, The Anxiety of Responsible Men, is forthcoming from Noemi Press in 2018, and A Body of Athletics, an anthology of Hannah Ensor contemporary sports literature co-edited with Natalie Diaz, is Photo Credit: Aisha Sabatini Sloan forthcoming from University of Nebraska Press. We’re very happy to report that Jesmyn Ward was made a 2017 MacArthur Fellow for her fiction, in which she explores “the enduring bonds of community and familial love among poor African Americans of the rural South against a landscape of circumscribed possibilities and lost potential.” She will receive $625,000 over five years to spend any way she chooses. -

Colombia Among Top Picks for Nobel Peace Prize 30 September 2016

Colombia among top picks for Nobel Peace Prize 30 September 2016 The architects of a historic accord to end "My hope is that today's Nobel Committee in Oslo Colombia's 52-year war are among the favourites is inspired by their predecessors' decision to award to win this year's Nobel Peace Prize as speculation the 1993 prize to Nelson Mandela and FW de mounts ahead of next week's honours. Klerk, architects of the peaceful end of apartheid," he told AFP. The awards season opens Monday with the announcement of the medicine prize laureates in That prize came "at a time when the outcome of the Stockholm, but the most keenly-watched award is transition was uncertain, and with the aim of that for peace on October 7. encouraging all parties to a peaceful outcome, and it succeeded." The Norwegian Nobel Institute has received a whopping 376 nominations for the peace prize, a His counterpart at Oslo's Peace Research Institute huge increase from the previous record of 278 in (PRIO), Kristian Berg Harpviken, agreed. 2014—so guessing the winner is anybody's game. "Both parties have been willing to tackle the difficult Experts, online betting sites and commentators issues, and a closure of the conflict is looking have all placed the Colombian government and increasingly irreversible," he said. leftist FARC rebels on their lists of likely laureates. Or maybe migrants Other names featuring prominently are Russian rights activist Svetlana Gannushkina, the Yet Harpviken's first choice was Gannushkina. negotiators behind Iran's nuclear deal Ernest Moniz of the US and Ali Akbar Salehi of Iran, Capping her decades-long struggle for the rights of Greek islanders helping desperate migrants, as refugees and migrants in Russia would send a well as Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege who strong signal at a time when "refugee hosting is helps rape victims, and US fugitive whistleblower becoming alarmingly contentious across the West" Edward Snowden. -

JBS 15 DEC Yk.Indd

When Autocracies Have No Respect for the Nobel Prize BY INA SHAKHRAI As both the fi rst writer and the fi rst woman from Belarus to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, Svetlana Alexievich became a centre of public attention worldwide. While the fi rst tweets from the Nobel announcement room generated some confusion regarding this unknown writer from an unknown land – with about “10,000 reporters googling Svetlana Alexievich” (Brooks 2015) – the subsequent media coverage of the writer in such publications as The Guardian, The New Yorker, and Der Spiegel sketched out a broad picture of Alexievich’s life, career and main works. Meanwhile, the Belarusian state media remained reluctant to give the award much attention: the upcoming presidential elections and Lukashenka’s visit to Turkmenistan took priority. In a couple of cafes and art spaces in Minsk young people gathered to watch Alexievich’s speech live via the Internet. Independent and alternative websites offered platforms for discussion and the exchange of opinions. Interestingly, the general public was divided over the question of the “Belarusianness” of Alexievich. The identity of the protagonist in Alexievich’s books caused a heated discussion among Russian intellectuals as well. They could hardly accept that Alexievich’s works might epitomize the experience of a genuinely Soviet individual, as they set out to. There was also much speculation on whether Alexievich should be acknowledged as a Russian writer, or whether the West treated her as Belarusian in order to chastise Russia. The events surrounding Alexievich’s Nobel Prize represent a revealing example of the all-encompassing nature of autocratic political systems, as well as how confusing and interwoven national identities can be. -

THE LAWRENCIAN CHRONICLE Vol

THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF SLAVIC LANGUAGES & LITERATURES THE LAWRENCIAN CHRONICLE Vol. XXX no. 1 Fall 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Chair’s Corner .....................................................................3 Message from the Director of Graduate Studies ..................5 Message from the Director of Undergraduate Studies ........6 “Postcards Lviv” .................................................................8 Faculty News ........................................................................9 Alumni News ......................................................................13 2 Lawrencían Chronicle, Fall 2019 Fall Chronicle, Lawrencían various levels, as well as become familiar with different CHAIR’S CORNER aspects of Central Asian culture and politics. For the depart- by Ani Kokobobo ment’s larger mission, this expansion leads us to be more inclusive and consider the region in broader and less Euro- centric terms. Dear friends – Colleagues travel throughout the country and abroad to present The academic year is their impressive research. Stephen Dickey presented a keynote running at full steam lecture at the Slavic Cognitive Linguistics Association confer- here in Lawrence and ence at Harvard. Marc Greenberg participated in the Language I’m thrilled to share Contact Commission, Congress of Slavists in Germany, while some of what we are do- Vitaly Chernetsky attended the ALTA translation conference in ing at KU Slavic with Rochester, NY. Finally, with the help of the Conrad fund, gen- you. erously sustained over the years by the family of Prof. Joseph Conrad, we were able to fund three graduate students (Oksana We had our “Balancing Husieva, Devin McFadden, and Ekaterina Chelpanova) to Work and Life in Aca- present papers at the national ASEEES conference in San demia” graduate student Francisco. We are deeply grateful for this support. workshop in early September with Andy Denning (History) and Alesha Doan (WGSS/SPAA), which was attended by Finally, our Slavic, Eastern European, and Eurasian Studies students in History, Spanish, and Slavic. -

Margaret Atwood 2017

Emcke 2016 Kermani 2015 Lanier 2014 Margaret Atwood 2017 Alexijewitsch 2013 Liao 2012 Sansal 2011 Grossman 2010 Magris 2009 Kiefer 2008 Friedländer 2007 Lepenies 2006 Pamuk 2005 Esterházy 2004 Sontag 2003 Conferment speeches Achebe 2002 Habermas 2001 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade 2017 Djebar 2000 Sunday, October 15, 2017 Stern 1999 Walser 1998 Kemal 1997 Vargas Llosa 1996 Schimmel 1995 Semprún 1994 Schorlemmer 1993 Oz 1992 Konrád 1991 Dedecius 1990 Havel 1989 Lenz 1988 Jonas 1987 Bartoszewski 1986 Kollek 1985 Paz 1984 The spoken word prevails. Sperber 1983 Kennan 1982 Kopelew 1981 Cardenal 1980 Menuhin 1979 Lindgren 1978 Kołakowski 1977 Frisch 1976 Grosser 1975 Frère Roger 1974 The Club of Rome 1973 Korczak 1972 Dönhoff 1971 Myrdal 1970 Mitscherlich 1969 Senghor 1968 Bloch 1967 Bea/Visser 't Hooft 1966 Sachs 1965 Marcel 1964 Weizsäcker 1963 Hinweis: Die ausschließlichen Rechte für die Reden liegen bei den Autoren. Tillich 1962 Radhakrishnan 1961 Die Nutzung der Texte ist ohne ausdrückliche Lizenz nicht gestattet, sofern Gollancz 1960 nicht gesetzliche Bestimmungen eine Nutzung ausnahmsweise erlauben. Heuss 1959 Jaspers 1958 Wilder 1957 Schneider 1956 Hesse 1955 Burckhardt 1954 Buber 1953 Guardini 1952 Schweitzer 1951 Tau 1950 Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels 2017 Peter Feldmann Lord Mayor of the City of Frankfurt Greeting On behalf of the City of Frankfurt, I would like what I can say with confidence is that I and many to welcome you to the presentation of this year’s other readers know that your books have changed Peace Prize of the German Book Trade to Margaret our world. Among many other things, you have Atwood. -

![THE THEOLOGICAL ]OURNAL Or EMANUEL UMVERSITY OT ORADEA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1991/the-theological-ournal-or-emanuel-umversity-ot-oradea-711991.webp)

THE THEOLOGICAL ]OURNAL Or EMANUEL UMVERSITY OT ORADEA

Perichoresis THE THEOLOGICAL ]OURNAL or EMANUEL UMVERSITY OTORADEA VOLI.JME5 ISSUE1 2007 EMANI.JELI.JNIYERSTry PUBLISHING HOUSE BOARD OF EDITORS Prof. Dr. PAL'I,NEGRUT, The Rector of Emanuel University (Systematic Theology) Dr. Manrus D. CnucrRU, Editor-in-Chief (Patristics and Classical Languages) Dr. Dr. CoRNELT C. Sn4LT' Asst. Editor-in-Chief (Reformation Studies, Historical and Dognatic Theology) Dr. oer.ie. Bolce, Theological Editor (Old and New Testament Studies) EDITORIAL AD\'ISORS Prof. Dr. DIHC. JAMESMCMAHoN, Albert E[is Institute (APPlied Theology) hof. Dr, FRANKA. JAMFGIn, Reformed Theological Seminary (Reformation Studies) Prof. Dr. HAMILToN MooRE, tish Baptist College, Queerls University of Belfasi (BiblicalTheology) Asst. Prof, Dr. STEvENSvmr, Southwesterri-Biptist Theological Seminary (flomiletics and Pastoral Theology) MANAGING EDITOR Dr. D!. CoRNELT C. Sn.{u,r The theoloqical researchof Emanuel University is developed mairrly by The Faculty .,i fn"oto.i attd the Brian CriIfiths School of Management The researchactivity of tfr" i"*if,i.f fn"of"gy is carried out by the following departments: The Seminar of ftr"oloeicit Res"utci, The Cenhe foi Reformation studjes, The Centre for Mis- .ioi"aiJ st"ai"", fn" centre for Pastoral counselling, and the Billy Graham Chair of Evangelism, Peicharesists Dublished twice a year at the end of each acadernic semestre (March utti S.ot"-#t) by The Faculty of Theology and The Brian Griffitfu School of Vun"gL*"nt itt.otperation wiih colleagues and contributors from abroad Thus' the idias expressed in various articles may not rePresent the formal dogmatic confession ofEmaruel University and they should be acknowledged as such' For permission to reproduce information fuonPerichotesis, pleasewrite to the Boari of Editors at U'niversitatea Emanuel din Oradea/Emanuel University of OraJea, Facultatea de Teologie/The Faculty of Theology,St Nuflrului Nr' 8Z 410597Oradea, Bihor, Romfia/Romania, or to the Managing Editor at [email protected]. -

Session Slides

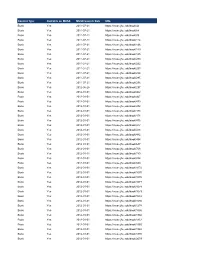

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

Descarcă Materialele

292 Preúedinte al ConferinĠei: Emilia Taraburcă, conferenĠiar universitar, doctor în filologie, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova Comitetul útiinĠific al ConferinĠei: Michèle Mattusch, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea Humboldt din Berlin, Germania. Petrea Lindenbauer, doctor habilitat, Institutul de Romanistică, Universitatea din Viena. profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Gheorghe Manolache, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Vasile Spiridon, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „V. Alecsandri” din Bacău, România. Al. Cistelecan, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea ”Petru Maior”, Tîrgu Mureú. Gheorghe Clitan, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat, Director al Departamentului de Filosofie úi ùtiinĠe ale Comunicării, Universitatea de Vest din Timiúoara. Ana Selejan, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Ludmila ZbanĠ, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Decanul FacultăĠii de Limbi úi Literaturi Străine, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova. Sergiu Pavlicenco, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova. Elena Prus, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Prorector pentru Cercetare ùtiinĠifică úi Studii Doctorale, ULIM. Ion Plămădeală, doctor habilitat în filologie, úeful sectorului de Teorie úi metodologie literară al Institutului de Filologie al AùM. Maria ùleahtiĠchi, doctor în filologie, secretar útiinĠific al SecĠiei -

Luise Haus',Intro

Introduction The Haushofers And The Nazis Luise Haushofer’s Jail Journal follows on from Albrecht Haushofer’s Moabite Sonnets, a bilingual edition of which appeared in 2001 with an introduction about the Haushofers, Geopolitics and the Second World War. Luise (née Renner) was Albrecht’s sister-in-law. After Moabite Sonnets appeared, her daughter—Andrea Haushofer-Schröder, Albrecht’s niece—contacted me and gave me some documents which illustrate the family consequences of Albrecht’s resistance activities. One of these was that Luise served time in jail as the Gestapo suspected her of helping Albrecht to elude capture after the 20th July 1944—a phrase which is shorthand for the attempt to assassinate Hitler and establish an alternative Government that would attempt to negotiate an end to the Second World War, and re-establish democracy in Germany. Because of the Nazi policy of Sippenhaft— arresting the family of an accused—Albrecht landed the Renner as well as the Haushofer families in trouble with the Gestapo and caused some dispute and ill- feeling between the two. The documents Andrea gave me appear here in the original German and in English translation. They comprise a communication from Martha Haushofer to Anna Renner; another from Karl Haushofer to Paul Renner; a reply from Renner; and a surviving fragment of a Jail Journal written by Luise Haushofer in 1963. In addition, there are several illustrations from the Haushofer archive (provided by Andrea). Albrecht was summarily executed in the closing hours of the War for his part in the Resistance to the Hitler regime. He had been captured in December 1944 and kept on ice in the Berlin Moabite Prison by the Nazis, in case his English contacts would be useful in the event of a negotiated end to the war. -

Melodrama After the Tears

Melodrama After the Tears Amsterdam UniversityPress Amsterdam UniversityPress Melodrama After the Tears New Perspectives on the Politics of Victimhood Scott Loren and Jörg Metelmann (eds.) Amsterdam UniversityPress Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Man Ray, “The Tears” (c. 1930) © Man Ray Trust / 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam AmsterdamLay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 673 6 e-isbn 978 90 4852University 357 3 doi 10.5117/9789089646736 nur 670 Press © The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2016 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Acknowledgements As part of the project entitled “Aesthetics of Irritation” (2010-2012), funding for this volume was generously provided by the “Kulturen, Institutionen, Märkte” (KIM) research cluster at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of St.Gallen, Switzerland. Many of the contributions to the volume were first presented in November 2011 at the conference “After the Tears: Victimhood and Subjectivity in the Melodramatic Mode,” also hosted by KIM and the University of St.Gallen, with the support of the Haniel Foundation Duisburg. -

Europa Liest – Literatur in Europa

Ausgabe 3/2010 KULTURREPORT KULTURREPORT Fortschritt Europa Fortschritt Europa Fortschritt Europa Europa liest – KULTURREPORT • • KULTURREPORT Literatur aus Europa ist weltweit bekannt und Literatur in Europa beliebt. Doch innerhalb Europas hält sich das Interesse untereinander in Grenzen. Über 50 Prozent aller Übersetzungen in andere europäi- sche Sprachen stammen aus dem Englischen oder Amerikanischen. Die dritte Ausgabe des Europa in Literatur – liest Europa Kulturreports beschäftigt sich mit der Literatur in Europa und dem europäischen Buchmarkt. Aus Sicht namhafter europäischer Autoren wie u.a. Umberto Eco, Rafik Schami, Tim Parks, oder Slavenka Drakulic wird die Rolle der Literatur und Kultur in Europa hinterfragt. Kann europäi- sche Literatur eine strategische Rolle überneh- men, um dem Kontinent zu einem noch immer vermissten Gemeinschaftsgefühl zu verhelfen? Welche Fortschritte oder Rückschritte sind in den letzten Jahren auf dem Weg zu einer euro- päischen Kultur zu verzeichnen? ISBN 978-3-921970-99-7 1 KULTURREPORT FORTSCHRITT EUROPA KULTURREPORT FORTSCHRITT EUROPA Von der Liebeserklä- rung bis zum sicheren Weg zum Ruhm Für den einen ist es ein Objekt größter Begierde, für den anderen ein Vehikel für den beruflichen Erfolg: Jeder Autor hat ein ganz persönliches Verhältnis zum Buch. Kann es die europäische Identität stärken? Welche Rolle spielt die Literatur in Europa? Umberto Eco, Rafik Schami, Ulrike Draesner, Tim Parks, Andrea Grill: Fünf der 33 Autoren aus 18 Ländern, die sich in dieser Ausgabe des Kulturreports mit der Literatur in Europa und dem europäischen Buchmarkt beschäftigten. Sie schreiben über die Liebe zum Buch, untersuchen das Leseverhalten in Eu- ropa, diskutieren die Zukunft des gedruckten Wortes und gehen der Frage nach, ob es eine europäische Literatur gibt. -

The Empty City an Original Essay by Darragh Mckeon

The Empty City book the About An Original Essay by Darragh McKeon All we have left is the place the attachment to the place we still rule over the ruins of temples spectres of gardens and houses if we lose the ruins nothing will be left —Zbigniew Herbert 1. We drive in through the main street, a two-lane road, the margin engulfed by weeds, the flanking tower blocks shrouded by fir trees. Craning my neck and looking up, I can see balconies that are overrun with creepers, their adjacent windows matte black with shadow, vacuums of habitation. Brown stains of carbonation run down from one floor to the next. It brings to mind an old man trailing gravy or tobacco juice down his chin. As we near the town centre, I feel a strong sense of dislocation, as if perhaps we shouldn’t be here. I assume this is because of the potential dangers of the place, the speculative health implications of our visit, or maybe it could be to do with the gravitas of its history; that coming to this town is an act of desecration or disrespect, as though we’re putting our dollar down for the freak show, about to enter the tent to gaze and point at the bearded lady or the three-legged man. But that’s not it, ̈ 3 AllThatIsSolidPS_2P.indd 3 2/11/14 4:21 PM About the book the About The Empty City (continued) I realise. We don’t belong here because nobody belongs here. Drive through a city, any city, even in the middle of the night, and there’s a bulb glowing over a lonely porch, a dog eyeing you suspiciously, or a closed-up petrol station, its owner sleeping upstairs.