JBS 15 DEC Yk.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marion Rutz Giessen University (Germany) Email: [email protected] ORCID

Pobrane z czasopisma Studia Bia?orutenistyczne http://bialorutenistyka.umcs.pl Data: 24/09/2021 16:34:20 DOI:10.17951/sb.2019.13.397-402 Studia Białorutenistyczne 13/2019 Reviews Marion Rutz Giessen University (Germany) Email: [email protected] ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2025-6068 Liberating the Past and Transgressing the National Simon Lewis, Belarus – Alternative Visions: Nation, Memory and Cosmopolita- nism, Routledge, New York/London, 2019 (BASEES / Routledge Series on Rus- sian and East European Studies). XI, 230 pp. n Slavic studies abroad, research on Belarusian literature is rare, and a monograph Ian event. This slender book evolved from Simon Lewis’s doctoral dissertation, sub- mitted at Cambridge University in 2014. It is a thorough study on the negotiations of nation and memory, with cosmopolitanism as a key word for the ‘alternative visions’ of the Belarus(ian) past, in which the author is interested most. The book concentrates on the second half of the 20th century and the post-Soviet period. As the first chapter offers an overview from ca. 1800, it doubles as an excellent introduction into modern Belarusian literature in general. The book must be praised particularly in this respect for its brevity and conciseness that completely differs from the multi-volume cumulati- ve histories of BelarusianUMCS literature published in Miensk, and from Arnold McMillin’s encyclopaedic publications over the last decades. The six chapters, as well as the end- notes that follow each of them, prove the author’s broad and thorough knowledge not only of the Belarusian classics, but also of Russian and Polish literature. -

Hopwood Newsletter Vol

Hopwood Newsletter Vol. LXXVIX, 1 lsa.umich.edu/hopwood January 2018 HOPWOOD The Hopwood Newsletter is published electronically twice a year, in January and July. It lists the publications and activities of winners of the Summer Hopwood Contest, Hopwood Underclassmen Contest, Graduate and Undergraduate Hopwood Contest, and the Hopwood Award Theodore Roethke Prize. Sad as I am to be leaving, I’m delighted to announce my replacement as the Hopwood Awards Program Assistant Director. Hannah is a Hopwood winner herself in Undergraduate Poetry in 2009. Her email address is [email protected], so you should address future newsletter items to her. Hannah Ensor is from Michigan and received her MFA in poetry at the University of Arizona. She joins the Hopwood Program from the University of Arizona Poetry Center, where she was the literary director, overseeing the Poetry Center’s reading & lecture series, classes & workshops program, student contests, and summer residency program. Hannah is a also co-editor of textsound.org (with poet and Michigan alumna Laura Wetherington), a contributing poetry editor for DIAGRAM, and has served as president of the board of directors of Casa Libre en la Solana, a literary arts nonprofit in Tucson, Arizona. Her first book of poetry, The Anxiety of Responsible Men, is forthcoming from Noemi Press in 2018, and A Body of Athletics, an anthology of Hannah Ensor contemporary sports literature co-edited with Natalie Diaz, is Photo Credit: Aisha Sabatini Sloan forthcoming from University of Nebraska Press. We’re very happy to report that Jesmyn Ward was made a 2017 MacArthur Fellow for her fiction, in which she explores “the enduring bonds of community and familial love among poor African Americans of the rural South against a landscape of circumscribed possibilities and lost potential.” She will receive $625,000 over five years to spend any way she chooses. -

Argentuscon Had Four Panelists Piece, on December 17

Matthew Appleton Georges Dodds Richard Horton Sheryl Birkhead Howard Andrew Jones Brad Foster Fred Lerner Deb Kosiba James D. Nicoll Rotsler John O’Neill Taral Wayne Mike Resnick Peter Sands Steven H Silver Allen Steele Michael D. Thomas Fred Lerner takes us on a literary journey to Portugal, From the Mine as he prepared for his own journey to the old Roman province of Lusitania. He looks at the writing of two ast year’s issue was published on Christmas Eve. Portuguese authors who are practically unknown to the This year, it looks like I’ll get it out earlier, but not Anglophonic world. L by much since I’m writing this, which is the last And just as the ArgentusCon had four panelists piece, on December 17. discussing a single topic, the first four articles are also on What isn’t in this issue is the mock section. It has the same topic, although the authors tackled them always been the most difficult section to put together and separately (mostly). I asked Rich Horton, John O’Neill, I just couldn’t get enough pieces to Georges Dodds, and Howard Andrew Jones make it happen this issue. All my to compile of list of ten books each that are fault, not the fault of those who sent out of print and should be brought back into me submissions. The mock section print. When I asked, knowing something of may return in the 2008 issue, or it may their proclivities, I had a feeling I’d know not. I have found something else I what types of books would show up, if not think might be its replacement, which the specifics. -

Colombia Among Top Picks for Nobel Peace Prize 30 September 2016

Colombia among top picks for Nobel Peace Prize 30 September 2016 The architects of a historic accord to end "My hope is that today's Nobel Committee in Oslo Colombia's 52-year war are among the favourites is inspired by their predecessors' decision to award to win this year's Nobel Peace Prize as speculation the 1993 prize to Nelson Mandela and FW de mounts ahead of next week's honours. Klerk, architects of the peaceful end of apartheid," he told AFP. The awards season opens Monday with the announcement of the medicine prize laureates in That prize came "at a time when the outcome of the Stockholm, but the most keenly-watched award is transition was uncertain, and with the aim of that for peace on October 7. encouraging all parties to a peaceful outcome, and it succeeded." The Norwegian Nobel Institute has received a whopping 376 nominations for the peace prize, a His counterpart at Oslo's Peace Research Institute huge increase from the previous record of 278 in (PRIO), Kristian Berg Harpviken, agreed. 2014—so guessing the winner is anybody's game. "Both parties have been willing to tackle the difficult Experts, online betting sites and commentators issues, and a closure of the conflict is looking have all placed the Colombian government and increasingly irreversible," he said. leftist FARC rebels on their lists of likely laureates. Or maybe migrants Other names featuring prominently are Russian rights activist Svetlana Gannushkina, the Yet Harpviken's first choice was Gannushkina. negotiators behind Iran's nuclear deal Ernest Moniz of the US and Ali Akbar Salehi of Iran, Capping her decades-long struggle for the rights of Greek islanders helping desperate migrants, as refugees and migrants in Russia would send a well as Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege who strong signal at a time when "refugee hosting is helps rape victims, and US fugitive whistleblower becoming alarmingly contentious across the West" Edward Snowden. -

THE LAWRENCIAN CHRONICLE Vol

THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS DEPARTMENT OF SLAVIC LANGUAGES & LITERATURES THE LAWRENCIAN CHRONICLE Vol. XXX no. 1 Fall 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Chair’s Corner .....................................................................3 Message from the Director of Graduate Studies ..................5 Message from the Director of Undergraduate Studies ........6 “Postcards Lviv” .................................................................8 Faculty News ........................................................................9 Alumni News ......................................................................13 2 Lawrencían Chronicle, Fall 2019 Fall Chronicle, Lawrencían various levels, as well as become familiar with different CHAIR’S CORNER aspects of Central Asian culture and politics. For the depart- by Ani Kokobobo ment’s larger mission, this expansion leads us to be more inclusive and consider the region in broader and less Euro- centric terms. Dear friends – Colleagues travel throughout the country and abroad to present The academic year is their impressive research. Stephen Dickey presented a keynote running at full steam lecture at the Slavic Cognitive Linguistics Association confer- here in Lawrence and ence at Harvard. Marc Greenberg participated in the Language I’m thrilled to share Contact Commission, Congress of Slavists in Germany, while some of what we are do- Vitaly Chernetsky attended the ALTA translation conference in ing at KU Slavic with Rochester, NY. Finally, with the help of the Conrad fund, gen- you. erously sustained over the years by the family of Prof. Joseph Conrad, we were able to fund three graduate students (Oksana We had our “Balancing Husieva, Devin McFadden, and Ekaterina Chelpanova) to Work and Life in Aca- present papers at the national ASEEES conference in San demia” graduate student Francisco. We are deeply grateful for this support. workshop in early September with Andy Denning (History) and Alesha Doan (WGSS/SPAA), which was attended by Finally, our Slavic, Eastern European, and Eurasian Studies students in History, Spanish, and Slavic. -

Winter 2017 Newsletter

Winter 2017 Newsletter Letter from Chair Katarzyna Dziwirek Łysak, a former Polish Fulbright Our faculty are working lecturer at UW, came back this hard on their classes and fall to give a lecture based on research. Prof. Galya Diment’s his new book, From Newsreel to article on Nabokov and Epilepsy Posttraumatic Films: Classic appeared in the August issue of Documentaries about the Times Literary Supplement. Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Her article on Chagall's Holocaust theme will be Struggle with Fatherhood continued in February when the appeared in the August issue of department will cosponsor an Tablet. She also wrote an exhibit at the Allen Library introduction for a new entitled They Risked Their translation of Ivan Goncharov's Lives: Poles who saved Jews The Same Old Story, which will during the Holocaust. (More on be published late in 2016. Dear Friends of the Slavic this in the article by Krystyna Department, Untersteiner in this issue.) As far as Slovenian Contents Thankfully, the last six studies are concerned, we months have been fairly received two sizeable donations uneventful, at least as far as the which allowed us to establish a 1-2 Letter from the Chair department was concerned. Our Slovenian Studies Endowment new administrator, Chris Fund. (More on this in the 2 New Administrator Dawson-Ripley, has settled in article by Dr. Michael Biggins 2-3 UW Polish Studies nicely and the department in this issue.) We also hosted operates as smoothly as ever. two Slovenian scholars: Milena 3-5 Student News We had a number of events Blažić and Vesna Mikolič, who since we came back this fall, gave talks on Slovenian 5 Slovene Studies with particular emphasis on children’s literature and tourism 6 -7 Startalk Program Polish and Slovenian. -

Session Slides

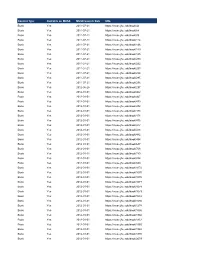

Content Type Available on MUSE MUSE Launch Date URL Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/42 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/89 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/114 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/146 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/149 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/185 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/280 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/292 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/293 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/294 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/295 Book Yes 2011-07-21 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/296 Book Yes 2012-06-26 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/297 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/462 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/467 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/470 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/472 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/473 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/474 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/475 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/477 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/478 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/482 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/494 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/687 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/708 Book Yes 2012-01-11 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/780 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/834 Book Yes 2012-01-01 https://muse.jhu.edu/book/840 Book Yes 2012-01-01 -

Names in Multi-Lingual, -Cultural and -Ethic Contact

Oliviu Felecan, Romania 399 Romanian-Ukrainian Connections in the Anthroponymy of the Northwestern Part of Romania Oliviu Felecan Romania Abstract The first contacts between Romance speakers and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. These contacts continued through the centuries till now. This paper approaches the Romanian – Ukrainian connection from the perspective of the contemporary names given in the Northwestern part of Romania. The linguistic contact is very significant in regions like Maramureş and Bukovina. We have chosen to study the Maramureş area, as its ethnic composition is a very appropriate starting point for our research. The unity or the coherence in the field of anthroponymy in any of the pilot localities may be the result of the multiculturalism that is typical for the Central European area, a phenomenon that is fairly reflected at the linguistic and onomastic level. Several languages are used simultaneously, and people sometimes mix words so that speakers of different ethnic origins can send a message and make themselves understood in a better way. At the same time, there are common first names (Adrian, Ana, Daniel, Florin, Gheorghe, Maria, Mihai, Ştefan) and others borrowed from English (Brian Ronald, Johny, Nicolas, Richard, Ray), Romance languages (Alessandro, Daniele, Anne, Marie, Carlos, Miguel, Joao), German (Adolf, Michaela), and other languages. *** The first contacts between the Romance natives and the Slavic people took place between the 7th and the 11th centuries both to the North and to the South of the Danube. As a result, some words from all the fields of onomasiology were borrowed, and the phonological system was changed, once the consonants h, j and z entered the language. -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

Books by Zina J. Gimpelevich: Excerpts from Some Reviews Vasil Byka Ŭ His Life and Works (English)

1 Books by Zina J. Gimpelevich: Excerpts from Some Reviews Vasil Byka ŭ His Life and Works (English) . Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2005. Bibliography. Index. Photographs. Translitera- tion. xi + 260. Endorsement: Vaclav Havel 2 Books by Zina J. Gimpelevich: Excerpts from Some Reviews Vasil Byka ŭ His Life and Works (English) . Montreal: McGill-Queen’s UP, 2005. Bibliography. Index. Photographs. Translitera- tion. xi + 260. Endorsement: Considered the best modern Belarusian writer and the last East European literary dissident, Vasil Byka ŭ (1924-2003) is re- ferred to as “conscience of a nation” for leading an intellectual cru- sade against Lukašenka’s totalitarian regime. In exile from Belarus for several years, he was given refuge by Vaclav Havel. He has been nominated for the Nobel Prize by Havel, Czesław Milosz, and PEN. Choice, 2006: Offering the first English-language study of this Bela- rusian writer (Vasil Byka ŭ 1924-2003), Z. Gimpelevich (University of Waterloo), treats each of Byka ŭ’s novels and several of his stories, stressing the writer’s passionate “war against human injustices.” Summing Up: Recommended. Upper-division undergraduates and above. — N. Titler, SUNY at Binghamton. Slavic Review, 2006: This study succeeds in exploring the ways in which Byka ŭ countered the prevailing official culture of the Soviet Union through his writing, while still continue to publish and reach a wide readership. It also emphasizes Byka ŭ’s Belarusian identity, and the important place it occupies in his writing, and reminds the reader to be wary of Soviet-era Russian translations of his work, which pro- vide a telling example how translation can shade into rewriting. -

Descarcă Materialele

292 Preúedinte al ConferinĠei: Emilia Taraburcă, conferenĠiar universitar, doctor în filologie, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova Comitetul útiinĠific al ConferinĠei: Michèle Mattusch, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea Humboldt din Berlin, Germania. Petrea Lindenbauer, doctor habilitat, Institutul de Romanistică, Universitatea din Viena. profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Gheorghe Manolache, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Vasile Spiridon, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „V. Alecsandri” din Bacău, România. Al. Cistelecan, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea ”Petru Maior”, Tîrgu Mureú. Gheorghe Clitan, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat, Director al Departamentului de Filosofie úi ùtiinĠe ale Comunicării, Universitatea de Vest din Timiúoara. Ana Selejan, profesor universitar, doctor, Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu, România. Ludmila ZbanĠ, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Decanul FacultăĠii de Limbi úi Literaturi Străine, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova. Sergiu Pavlicenco, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Universitatea de Stat din Moldova. Elena Prus, profesor universitar, doctor habilitat în filologie, Prorector pentru Cercetare ùtiinĠifică úi Studii Doctorale, ULIM. Ion Plămădeală, doctor habilitat în filologie, úeful sectorului de Teorie úi metodologie literară al Institutului de Filologie al AùM. Maria ùleahtiĠchi, doctor în filologie, secretar útiinĠific al SecĠiei -

Reviving Orthodoxy in Russia: Four Factions in the Orthodox Church

TITLE: REVIVING ORTHODOXY IN RUSSIA: FOUR FACTIONS IN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AUTHOR: RALPH DELLA CAVA, Queens College, CUNY THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE VIII PROGRAM 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION:1 CONTRACTOR: Queens College, CUNY PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Ralph Della Cava COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER: 810-02 DATE: December 6, 1996 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded by Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within the Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, or make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without the written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law. 1 The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s). CONTENTS Abstract 1 The Ultranationalists 3 The Ecumentists 4 The Institutionalists 5 Intra-Orthodox Division & External Religious Threat 6 Symbolic Responses 8 Organizational Responses 9 The Four New Departments 11 The Pastoralists 15 Conclusion 20 Endnotes 22 REVIVING ORTHODOXY IN RUSSIA: FOUR FACTIONS IN THE RUSSIAN ORTHODOX CHURCH Ralph Delia Cava Abstract Orthodoxy today is Russia's numerically largest confession and has for more than a millennium remained one and indivisible with the culture of the Eastern Slavs (including Byelorussians and Ukrainians).