The Power Behind the Pudding: Hidden Hierarchies in the African Colonial Cookery Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KARIBU | MURAKAZE | SOO DHOWOOW | BEM VINDO | BOYEYI MALAMU FREE in This Issue Juneteenth

July 2021 • Vol 4 / No 4 Understanding, Embracing, and Celebrating Diversity in Maine WELCOME | BIENVENUE | KARIBU | MURAKAZE | SOO DHOWOOW | BEM VINDO | BOYEYI MALAMU FREE In this Issue Juneteenth..................................2 Beautiful Blackbird Festival.....3 Publisher’s Editorial..................6 Immigration & the workforce.11 Finding freedom from Trauma Part II..................................12/19 World Market Basket .............14 Food for All Mobile Market African beef & sauce with Eugénie Kipoy Nouveaux Romans: reviews of recent novels by Francophone authors A partnership with Bates College .......................15/16/17 Sending money home ............20 Finance.....................................21 Columns. ......................24/25/26 Nigeria bans Twitter...............27 Bombay Mahal ........................28 Tips&Info for Maine ..............29 ICE in Maine..................30/31 Translations French.................................8 “I wish my teacher knew...” Swahili ................................9 ose interested in knowing more about the internal worlds of young people during the pandemic from Somali...............................10 their own points of view will want to head to Lewiston Public Library, where the digital art show “I wish Kinyarwanda.....................22 my teacher knew…” is on display until August 15. e show is the result of a collaboration between two Portuguese.........................23 educators at Lewiston High School, Deanna Ehrhardt and Sarah Greaney, and students. e work is raw -

Gastronomia E Higiene Alimentar

08.02 GASTRONOMIA E HIGIENE ALIMENTAR Pré-Requisitos Sem Pré-Requisitos As questões relacionadas com a gastronomia e higiene alimentar têm tido uma importância crescente devido à consciencialização por parte dos consumidores e dos operadores do sector alimentar no que diz respeito às suas obrigações. CONTEÚDOS PROGRAMÁTICOS OBJECTIVOS Módulo 1 - Gastronomia No final do curso, os formandos conhecerão as técnicas de - Técnicas de Produção Alimentar produção alimentar; as técnicas de higiene e os instrumentos - Preparação de gestão da produção. - Confecção - Empratamento DESTINATÁRIOS - Economia Alimentar - Cozinha Angolana Empresários, gestores, directores, quadros médios - Cozinha Portuguesa e superiores de instituições públicas e privadas com - Entradas responsabilidades na área da restauração; todos os interessados em adquirir conhecimentos nesta área. - Peixe/Carne - Sobremesa - Cozinha Internacional Módulo 2 - Alimentação Saudável e Nutrição - Noções Básicas – Variedade, Qualidade e Quantidade - Roda dos Alimentos - Nutrientes - Recomendações Módulo 3 - Higiene e Segurança Alimentar - Noções Básicas – Condições de Vida dos Microrganismos - Higiene Pessoal - Estado de Saúde - Atitude e Procedimentos - Instalações, Equipamento e Materiais INFORMAÇÕES - Procedimentos a Aplicar Horas: 40h - Utilização dos Produtos Horário: Consultar Plano de Formação - Circuito de Recolha, Separação e Eliminação de Lixos Material Entregue: Material de Apoio à Formação - Higiene e Conservação dos Alimentos Formação: Presencial - Recepção Regime: Laboral -

Memorandum N° 69/2015 | 29/04/2015

1 MEMORANDUM N° 69/2015 | 29/04/2015 The Memorandum is issued daily, with the sole purpose to provide updated basic business and economic information on Africa, to more than 4,000 European Companies, as well as their business parties in Africa. More than 1335 Memoranda issued from 2006 to 2014. More than 16,000 pages of Business Clips issued covering all African, European Institutions and African Union, as well as the Breton Woods Institutions. The subscription is free of charge, and sponsored by various Development Organisations and Corporations. Should a reader require a copy of the Memoranda, please address the request to fernando.matos.rosa@sapo or [email protected]. 2006 – 2015, 9 Years devoted to reinforce Europe – Africa Business and Development SUMMARY EC contributes EUR 295 million in additional resources to the Neighbourhood Investment Facility Page 2 EU proposes to boost humanitarian aid by €50 million as Commissioner Stylianides visits South Sudan Page 2 Nigeria: Edo Discovers Large Coal Deposit - Could Generate 1,200MW Electricity for Decades Page 3 Maputo/Catembe Bridge, in Mozambique, to open in 2017 Page 3 Lesotho: Basotho must benefit from “White Gold” Page 4 Government of Angola wants to bring an end to beef imports Page 4 EBRD and EU help Moroccan hi-tech financial services company achieve growth Page 4 Angola will have another 25 hotels by the end of the year Page 5 Think Tank event in Tunis: exploiting the potential of satellite navigation for road regulated applications Page 5 Commissioner Hahn in Tunisia -

Advancedaudioblogs3#1 Peruviancuisine:Lacomida Peruana

LESSON NOTES Advanced Audio Blog S3 #1 Peruvian Cuisine: La Comida Peruana CONTENTS 2 Dialogue - Spanish 4 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 5 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2020 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. DIALOGUE - SPANISH MAIN 1. Hola a todos! 2. Alguno ya tuvo la oportunidad de degustar algún plato típico peruano? 3. La comida peruana es una de las cocinas más diversas del mundo, incluso han llegado a decir que la cocina peruana compite con cocinas de alto nivel como la francesa y china. 4. La comida peruana es de gran diversidad gracias al aporte de diversas culturas como la española, italiana, francesa, china, japonesa, entre otras, originando de esta manera una fusión exquisita de distintos ingredientes y sabores que dieron lugar a distintos platos de comida peruana. 5. A este aporte multicultural a la cocina peruana, se suman la diversidad geográfica del país (el Perú posee 84 de las 104 zonas climáticas de la tierra) permitiendo el cultivo de gran variedad de frutas y verduras durante todo el año. 6. Asimismo el Perú tiene la bendición de limitar con el Océano Pacífico, permitiendo a los peruanos el consumo de diversos platos basados en pescados y mariscos. 7. La comida peruana ha venido obteniendo un reconocimiento internacional principalmente a partir de los años 90 gracias al trabajo de muchos chefs que se encargaron de difundir la comida peruana en el mundo y desde entonces cada vez más gente se rinde ante la exquisita cocina peruana. 8. En el año 2006, Lima, la capital del Perú, fue declarada capital gastronómica de América durante la Cuarta Cumbre Internacional de Gastronomía Madrid Fusión 2006. -

The Best 25 the Best of the Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 Years in Each Category for Each Country

1995-2020 The Best 25 The Best of The Best - 1995-2020 List of the Best for 25 years in each category for each country It includes a selection of the Best from two previous anniversary events - 12 years at Frankfurt Old Opera House - 20 years at Frankfurt Book Fair Theater - 25 years will be celebrated in Paris June 3-7 and China November 1-4 ALL past Best in the World are welcome at our events. The list below is a shortlist with a limited selection of excellent books mostly still available. Some have updated new editions. There is only one book per country in each category Countries Total = 106 Algeria to Zimbabwe 96 UN members, 6 Regions, 4 International organizations = Total 106 TRENDS THE CONTINENTS SHIFT The Best in the World By continents 1995-2019 1995-2009 France ........................11% .............. 13% ........... -2 Other Europe ..............38% ............. 44% ..........- 6 China .........................8% ............... 3% .......... + 5 Other Asia Pacific .......20% ............. 15% ......... + 5 Latin America .............11% ............... 5% .......... + 6 Anglo America ..............9% ............... 18% ...........- 9 Africa .......................... 3 ...................2 ........... + 1 Total _______________ 100% _______100% ______ The shift 2009-2019 in the Best in the World is clear, from the West to the East, from the North to the South. It reflects the investments in quality for the new middle class that buys cookbooks. The middle class is stagnating at best in the West and North, while rising fast in the East and South. Today 85% of the world middleclass is in Asia. Do read Factfulness by Hans Rosling, “a hopeful book about the potential for human progress” says President Barack Obama. -

BI 074-081 Luanda

Both Luanda may have been designated the most expensive city in the world for expats for the third consecutive year, sides of but this fascinating capital still has options for every pocket, finds the coin Lula Ahrens PLACES TO SEE n August last year, it happened again. As with many African countries, staples such as rice and Kizomba, a sensual, African dance genre characterised The same murmurs of surprise rippled beans feature heavily in Angolan cuisine as well as fish, by its softer, more romantic rhythm, originated in across the globe when research bureau which is caught daily along the country’s wide coastal strip. Angola. Spectate or, perhaps, even join in with Luanda’s Mercer’s annual Cost of Living survey was Traditional dishes are an enthralling mix of traditional African best dancers, as well as others eager to learn and practise, published. High up the list, which identifies flavours – hot spices and peanut sauces – and Portuguese, a at Kizomba na Rua, or ‘Kizomba in the street’. Held at the the most expensive places to live if you’re an expatriate, hangover from the country’s colonial years. Head to Chicala, at seaside every Sunday at around 5.30pm, enjoy a few hours were all the usual suspects: Hong Kong, Singapore, Zurich, the cheap end of the city, to try proper, home-style local of alcohol – and money–free dancing. See the Facebook group Seoul. But first place for the third consecutive year went delicacies in restaurants like Bella Mar. A simple, typically for details. Once perfected, it’s worth taking your new moves to Luanda, the capital of Angola. -

Angola in Perspective

© DLIFLC Page | 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Geography ......................................................................................................... 5 Country Overview ........................................................................................................... 5 Geographic Regions and Topographic Features ............................................................. 5 Coastal Plain ............................................................................................................... 5 Hills and Mountains .................................................................................................... 6 Central-Eastern Highlands .......................................................................................... 6 Climate ............................................................................................................................ 7 Rivers .............................................................................................................................. 8 Major Cities .................................................................................................................... 9 Luanda....................................................................................................................... 10 Huambo ..................................................................................................................... 11 Benguela ................................................................................................................... 11 Cabinda -

EXPO2015. We Are There! Sustainable Farm Pavilion

THE WORLD OF NEW HOLLAND AGRICULTURE We are fi nally there. Until October 31st EXPO2015. the New Holland Sustainable Farm Pavilion We are there! at Expo 2015 displays our sustainable farming technologies. Sustainable Farm Pavilion EXPO2015. We are there! We are fi nally there. The New Holland Sustainable Farm Pavilion, at Expo 2015, will display our sustainable farming technologies until October 31st he New Holland Sustainable Farm Pavilion opened hours to which all farmers are accustomed. on May 1st ready to welcome over 20 million New Holland Agriculture is the only The Seeds of Life series is an important part of the Tvisitors who are expected to visit Milan for Expo experience within the Pavilion, as many visitors have little 2015, the Universal Exhibition. New Holland is a Global agricultural equipment manufacturer knowledge and awareness of agriculture. New Holland Partner of Expo Milano 2015and the only agricultural with its own pavilion participating in has made the visit to the Sustainable Farm Pavilion an equipment brand present at Expo 2015 as part of CNH the universal exhibition, whose theme enlightening experience. Industrial and Fiat Chrysler. The choice could not be The Pavilion itself is totally sustainable. Built without better given the Expo 2015 theme: Feeding the Planet, Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life concrete foundations, it is assembled on a steel framework Energy for Life. New Holland has actively pursued a perfectly represents the vision, the designed to be easily dismantled: no demolition work strategy for sustainable agriculture since 2006, when its mission and the values of our Clean will be needed nor any construction waste produced. -

Traditional Recipes from Angola B Page, Angolan Foods 09/10/13 21:37

Traditional Recipes from Angola b Page, Angolan Foods 09/10/13 21:37 Home Recipes Home African Recipes North African Recipes West African Recipes East African Recipes Southern African Recipes Forum Internet via satellite www.skyDSL.eu Non aspettate. Fino a 20.000 kbit/s Ordinate ora dal leader di mercato! Celtnet Recipes — The Recipes of Angola, b Page Search: Recipe Search Search Advanced Search Celtnet Needs Your Help Welcome to Celtnet Recipes, Please help support this site to keep it on the web! I have been personally funding this site for 8 the home of on-line food and Recipes. years now, but it has grown too large for its current hosting. I need to move hosting and I need to re-write 19 300 recipes, 10 free historic cookery books 180 wild foods the codebase. This is a lot of work and I need to raise money... You can donate via PayPal using the button, left, or you can buy one of the site's Kindle eBooks. Just think, a typical recipe book is $9.99 and you get 500 recipes. This site gives you the equivalent of almost 40 recipe books... and more. If you want to help, then you can learn more about this campaign's Help keep this site free and make it Ad-Free. aims on the Free Celtnet Recipes page or join the discussion at #HelpCeltnetRecipes. Follow us @celtnetrecipes. Go over to the Free Celtnet Recipes page and you can download a FREE Halloween recipes eBook there is also an unit converter you can add to your own site or blog. -

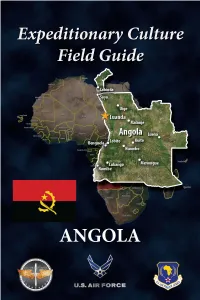

ECFG-Angola-2020R.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success. ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Angola Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Angola, focusing on unique cultural features of Angolan society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society. All human beings have culture, and individuals within a culture share a general set of beliefs and values. -

Universidade De São Paulo Faculdade De Filosofia

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS MODERNAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS EM INGLÊS ROZANE RODRIGUES REBECHI A imagem do brasileiro no discurso do norte-americano em livros de culinária típica: um estudo direcionado pelo corpus São Paulo 2010 i UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO FACULDADE DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS DEPARTAMENTO DE LETRAS MODERNAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ESTUDOS LINGUÍSTICOS E LITERÁRIOS EM INGLÊS A imagem do brasileiro no discurso do norte-americano em livros de culinária típica: um estudo direcionado pelo corpus Rozane Rodrigues Rebechi Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Linguísticos e Literários em Inglês do Departamento de Letras Modernas da Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Letras. Orientador: Profa. Dra. Stella Esther Ortweiler Tagnin São Paulo 2010 ii AUTORIZO A REPRODUÇÃO TOTAL OU PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO, POR QUALQUER MEIO CONVENCIONAL OU ELETRÔNICO, PARA FINS DE ESTUDO OU PESQUISA, DESDE QUE CITADA A FONTE. Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo Rebechi, Rozane Rodrigues. A imagem do brasileiro no discurso do norte-americano em livros de culinária típica: um estudo direcionado pelo corpus / Rozane Rodrigues Rebechi ; orientador : Stella Esther Ortweiler Tagnin. -- São Paulo, 2010. 220 f. Dissertação (Mestrado)--Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Letras Modernas. Área de concentração: Estudos Linguísticos e Literários em Inglês. 1. -

Angolan - CALULU DE PEIXE

Fish Stew with Okra & palm oil Angolan - CALULU DE PEIXE Meet calulu de peixe, a delectable and hearty fish and okra stew. It has become so beloved in Angola that you’d expect the recipe to have grown and matured with the culture. Alas, this would only be partly true. While the ingredients are quintessentially Angolan, it was a recipe developed in Brazil, another former Portuguese colony. Eventually, the recipe did make its way back to African shores, and it has become a staple in local Angolan cuisine since. 20 minutes PREP TIME INGREDIENTS 25 minutes COOK TIME • 1 pound of fish (can be smoked, dried, fresh or • 1 cup kale, chopped a combo of all three) • 1 tablespoon lemon juice • 3 garlic cloves, minced • 2 bay leaves • 2 medium-sized white onions, diced • 1 teaspoon sea salt • 3-4 medium-sized tomatoes, diced (keep the • 1 teaspoon freshly cracked black pepper juices!) • 1/4 cup red palm oil • 1-2 green chili peppers, very finely chopped (optional, but very recommended) • 1½ cups vegetable broth • 2 handfuls (1/2 cup) okra, trimmed and sliced • 2 teaspoons arrowroot starch or similar sauce diagonally thickener (optional) TOTAL TIME: 45 MINUTES SERVES: 4 PEOPLE LEVEL OF DIFFICULTY: EASY 1. ANGOLAN - CALULU DE PEIXE You can find out more about Angolan cuisine, its history and the Calulu de Peixe recipe (including more pictures) by clicking here. Stage 1: Marinate the Fish 1. Take a medium-sized mixing bowl and place your fish in the center 2. Pour your lemon juice, garlic and half of your green chili peppers over top, followed by salt and fresh cracked black pepper.