'We Have Become Niggers!': Josephine Baker As a Threat To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teilnachlass Max Reinhardt Wienbibliothek Im Rathaus Handschriftensammlung ZPH 989 Bestandssystematik

Teilnachlass Max Reinhardt Wienbibliothek im Rathaus Handschriftensammlung ZPH 989 Bestandssystematik Wienbibliothek im Rathaus/Handschriftensammlung - Teilnachlass Max Reinhardt / ZPH 989 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Biographische Informationen Reinhardt, Max (eigentlich: M. Goldmann): 9. 9. 1873 Baden - 31. 10. 1943 New York; Schauspieler, Regisseur, Theaterleiter; 1938 Emigration über London nach New York; Wien, Berlin, New York. Provenienz des Bestands Der Teilnachlass Max Reinhardt wurde von der Wienbibliothek im Rathaus im Jahr 1998 von einem Antiquariat gekauft. Umfang 16 Archivboxen, 1 Foliobox, 1 Großformatmappe. Information für die Benützung Die in geschwungenen Klammern angeführten Zahlen beziehen sich auf die jeweiligen Nummern in der Publikation: Max Reinhardt. Manuskripte, Briefe, Dokumente. Katalog der Sammlung Dr. Jürgen Stein. Bearbeitet und herausgegeben von Hugo Wetscherek. Für die Ordnungssystematik wurden alle Informationen aus der o.a. Publikation - inklusive Verweise auf angegebene Primär- und Sekundärliteratur - ohne Prüfung auf Richtigkeit mit Zustimmung des Herausgebers verwendet. Die Orthographie der Zitate wurde vereinheitlicht. 2 Wienbibliothek im Rathaus/Handschriftensammlung - Teilnachlass Max Reinhardt / ZPH 989 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abkürzungsverzeichnis Anm. Anmerkung(en) Beil. Beilage(n) -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

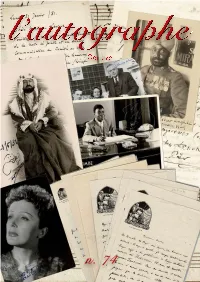

Genève L’Autographe

l’autographe Genève l’autographe L’autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201 Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in EURO and do not include postage. All overseas shipments will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefts of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, Paypal and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Postfnance CCP 61-374302-1 3, rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: CH 94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped via Federal Express on request. Music and theatre p. 4 Miscellaneous p. 38 Signed Pennants p. 98 Music and theatre 1. Julia Bartet (Paris, 1854 - Parigi, 1941) Comédie-Française Autograph letter signed, dated 11 Avril 1901 by the French actress. Bartet comments on a book a gentleman sent her: “...la lecture que je viens de faire ne me laisse qu’un regret, c’est que nous ne possédions pas, pour le Grand Siècle, quelque Traité pareil au vôtre. Nous saurions ainsi comment les gens de goût “les honnêtes gens” prononçaient au juste, la belle langue qu’ils ont créée...”. 2 pp. In fine condition. € 70 2. Philippe Chaperon (Paris, 1823 - Lagny-sur-Marne, 1906) Paris Opera Autograph letter signed, dated Chambéry, le 26 Décembre 1864 by the French scenic designer at the Paris Opera. -

Sujet E3C N°03827 Du Bac LVA Et LVB Allemand Première T3

ÉPREUVES COMMUNES DE CONTRÔLE CONTINU CLASSE : Première VOIE : ☐ Générale ☐ Technologique ☒ Toutes voies (LV) ENSEIGNEMENT : LV allemand DURÉE DE L’ÉPREUVE : 1h30 Niveaux visés (LV) : LVA B1-B2 LVB A2-B1 Axe de programme :1 CALCULATRICE AUTORISÉE : ☐Oui ☒ Non DICTIONNAIRE AUTORISÉ : ☐Oui ☒ Non ☐ Ce sujet contient des parties à rendre par le candidat avec sa copie. De ce fait, il ne peut être dupliqué et doit être imprimé pour chaque candidat afin d’assurer ensuite sa bonne numérisation. ☐ Ce sujet intègre des éléments en couleur. S’il est choisi par l’équipe pédagogique, il est nécessaire que chaque élève dispose d’une impression en couleur. ☐ Ce sujet contient des pièces jointes de type audio ou vidéo qu’il faudra télécharger et jouer le jour de l’épreuve. Nombre total de pages : 5 1/5 C1CALLE03827 SUJET LANGUES VIVANTES : ALLEMAND EVALUATION 2 Compréhension de l’écrit et expression écrite Niveaux visés Durée de l’épreuve Barème : 20 points LVA: B1-B2 CE: 10 points LVB: A2-B1 1h30 EE: 10 points L’ensemble du sujet porte sur l’axe 1 du programme : Identités et échanges Il s’organise en deux parties : 1- Compréhension de l’écrit 2- Expression écrite Vous disposez tout d’abord de cinq minutes pour prendre connaissance de l’intégralité du dossier. Vous organiserez votre temps comme vous le souhaitez pour rendre compte en allemand du document écrit (en suivant les indications données ci-dessous – partie 1) et pour traiter en allemand le sujet d’expression écrite (partie 2). Titre du document : Alte Heimat, neue Heimat 1. Compréhension de l'écrit a) Texte A und B: Lesen Sie beide Texte. -

Klimt and the Ringstrasse

— 1 — Klimt and the Ringstrasse Herausgegeben von Agnes Husslein-Arco und Alexander Klee Edited by Agnes Husslein-Arco and Alexander Klee Inhalt Agnes Husslein-Arco 9 Klimt und die Ringstraße Klimt and the Ringstrasse Cornelia Reiter 13 Die Schule von Carl Rahl. Eduard Bitterlichs Kartonzyklus für das Palais Epstein The Viennese School of Carl Rahl. Eduard Bitterlich’s series of cartoons for Palais Epstein Eric Anderson 23 Jakob von Falke und der Geschmack Jakob von Falke and Ringstrasse-era taste Markus Fellinger 35 Klimt, die Künstler-Compagnie und das Theater Klimt, the Künstler Compagnie, and the Theater Walter Krause 49 Europa und die Skulpturen der Wiener Ringstraße Europe and the Sculptures of the Ringstrasse Karlheinz Rossbacher 61 Salons und Salonièren der Ringstraßenzeit Salons and Salonnières of the Ringstrasse-era Gert Selle 77 Thonet Nr. 14 Thonet No. 14 Wiener Zeitung, 28. April 1867 84 Die Möbelexposition aus massiv gebogenem Längenholze der Herren Gebrüder Thonet The exhibition of solid bentwood furniture by Gebrüder Thonet Alexander Klee 87 Kunst begreifen. Die Funktion des Sammelns am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts in Wien Feeling Art. The role of collecting in the late nineteenth century in Vienna Alexander Klee 93 Anton Oelzelt. Baumagnat und Sammler Anton Oelzelt. Construction magnate and collector Alexander Klee 103 Friedrich Franz Josef Freiherr von Leitenberger. Das kosmopolitische Großbürgertum Baron Friedrich Franz Josef von Leitenberger. The cosmopolitan grande bourgeoisie Alexander Klee 111 Nicolaus Dumba. Philanthrop, -

Nachlass Albin Skoda Autographen

Nachlass Albin Skoda Autographen ABEKEN, Hedwig an Fräulein Schulhoff Berlin, 3. 11. 1901; Hs. [AM 38 802 Sk] ABEKEN, Hedwig an Fräulein Schulhoff o. D.; Hs [AM 38 801 Sk] ABEL, Katharina an Frau Werner Vorderbrühl, 14. 7. o. J.; Visitenkarte, Dr. mit hs. Ergänzung [AM 51 995 Sk] ACHTERBERG, Fritz an Unbekannt Berlin, o. D.; Hs. [AM 38 803 Sk] ADLER, Dr. Friedrich an Unbekannt Prag, 20. 5. 1910; Hs. [AM 38 804 Sk] ADOLPH, Karl an Comitee 21. 1. 1930; Hs. [AM 38 805 Sk] AKNAY, Vilma an Unbekannt Wien, 29. 3. 1923; Fragment, Dr. mit eh. Unterschrift [AM 57 366 Sk] ALBACH-RETTY, Rosa an Unbekannt 1912; Einreichung für Freikarten im Burgtheater, Dr. und Hs. mit eh. Unterschrift [AM 39 179 Sk] ALBACH-RETTY, Rosa an Unbekannt 1912; Einreichung für Freikarten im Burgtheater, Dr. und Hs. mit eh. Unterschrift [AM 39 180 Sk] ALBACH-RETTY, Rosa an Anna Witrofski-Kallina 2. 11. 1931; Hs. Beilage: Briefkuvert; Hs. [AM 38 806 Sk] ALEXANDROWA, Elisabeth 4. 6. o. J.; Bestätigung eines Abkommens mit den Reinhardt-Gastspielen an den Münchener Staatstheatern, Abschrift, Ms. [AM 57 641 Sk] ALXINGER, Johann Baptist an Hofrat Greiner o. D.; Hs. Beilage: K. Bulling an Unbekannt; Leipzig, 17. 7. 1912; Ms. (Durchschlag) [AM 38 807 Sk] ANDERGAST, Liesl an Albin Skoda o. D.; Hs. Beilage: Briefkuvert; Hs. [AM 38 808 Sk] ANDERGAST, Liesl u. a. o. D.; Namensliste zur Vorstellung „Pariserinnen“, Ms. mit eh. Unterschriften u. a. von Liesl Andergast, Pepi Kramer-Glöckner, Gisa Wurm, Elfriede Datzig, Anton Rudolph, Oskar Karlweis, Robert Horky, Martin Berliner, Leopoldine Richter [AM 57 367 Sk] ANDERS, Günther an Albin Skoda 22. -

The Museum of Modern Love Heather Rose

JULY 2017 The Museum of Modern Love Heather Rose Winner of the 2017 Stella Prize. A mesmerising literary novel about a lost man in search of connection - a meditation on love, art and commitment, set against the backdrop of one of the greatest art events in modern history, Marina Abramovic's The Artist is Present. Description Winner of the 2017 Stella Prize.'This is a weirdly beautiful book.' David Walsh founder and curator, MONA'Life beats down and crushes the soul, and art reminds you that you have one.' Stella Adler'Art will wake you up. Art will break your heart. There will be glorious days. If you want eternity you must be fearless.' From The Museum of Modern LoveShe watched as the final hours of The Artist is Present passed by, sitter after sitter in a gaze with the woman across the table. Jane felt she had witnessed a thing of inexplicable beauty among humans who had been drawn to this art and had found the reflection of a great mystery. What are we? How should we live?If this was a dream, then he wanted to know when it would end. Maybe it would end if he went to see Lydia. But it was the one thing he was not allowed to do.Arky Levin is a film composer in New York separated from his wife, who has asked him to keep one devastating promise. One day he finds his way to The Atrium at MOMA and sees Marina Abramovic in The Artist is Present. The performance continues for seventy-five days and, as it unfolds, so does Arky. -

Complete Issue

Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research Thematic Section: Pursuing the Trivial Edited by Roman Horak, Barbara Maly, Eva Schörgenhuber & Monika Seidl Extraction from Volume 5, 2013 Linköping University Electronic Press Culture Unbound: ISSN 2000-1525 (online) URL: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se/ © 2013 The Authors. Culture Unbound, Extraction from Volume 5, 2013 Thematic Section: Persuing the Trivial Barbara Maly, Roman Horak, Eva Schörgenhuber & Monika Seidl Introduction: Pursuing the Trivial ..................................................................................................... 481 Steven Gerrard The Great British Music Hall: Its importance to British culture and ‘The Trivial’ ........................... 487 Roman Horak ‘We Have Become Niggers!’: Josephine Baker as a Threat to Viennese Culture .............................. 515 Yi Chen ’Walking With’: A Rhythmanalysis of London’s East End ................................................................. 531 Georg Drennig Taking a Hike and Hucking the Stout: The Troublesome Legacy of the Sublime in Outdoor Recreation ............................................................................................................................ 551 Anna König A Stitch in Time: Changing Cultural Constructions of Craft and Mending ....................................... 569 Daniel Kilvington British Asians, Covert Racism and Exclusion in English Professional Football ............................... 587 Sabine Harrer From Losing to Loss: Exploring the Expressive -

Max Reinhardt Zim://A/Max Reinhardt.Html

Max_Reinhardt zim://A/Max_Reinhardt.html Max_Reinhardt Max Reinhardt (Baden, 9 settembre 1873 – New York, 31 ottobre 1943) è stato un regista teatrale, attore teatrale, produttore teatrale, drammaturgo e regista cinematografico austriaco naturalizzato statunitense. Biografia Max Reinhardt nacque nel 1873 a Baden, una cittadina termale a pochi chilometri da Vienna, residenza, dei soggiorni termali della famiglia imperiale, con il nome di Maximilian Goldmann in una famiglia ebraica appartenente all'alta borghesia austriaca. I teatri di Berlino Iniziò la sua carriera teatrale come attore ma non eccellendo nell'arte del recitare passò a fare Max Reinhardt il direttore di scena e infine il regista. Essendo passato attraverso l'esperienza del cabaret, quando si trasferì a Berlino, prese in gestione un locale che ben presto divenne famoso in tutta la città, il Cabaret Schall und Rauch. Questo fu il suo trampolino di lancio sulla scena berlinese che di lì a poco lo avrebbe visto diventare uno dei maggiori registi teatrali del Novecento. Divenuto amico di Otto Brahm, il celebre regista del teatro naturalista tedesco, Reinhardt lo affiancò nelle sue produzioni al Deutsches Theater, il più importante teatro berlinese. Reinhardt a Berlino Nel 1905 Reinhardt, essendo tramontato l'astro del naturalismo, fu chiamato ad assumere la conduzione del Deutsches Theater e sotto la sua supervisione nacquero delle produzioni spettacolari e modernissime come sino a quel momento non se ne erano mai viste di simili in Germania. Frequentò ogni genere teatrale privilegiando però le tragedie greche e i repertori shakespeariani. Passarono sotto la sua conduzione i più importanti uomini di teatro tedeschi del primo ventennio del Novecento. -

Vor Dem Vorhang Jahresbericht 2019 Das Jahr 2019 Stand Im Theatermuseum Ganz Im Überdauert Haben

Vor dem Vorhang Jahresbericht 2019 Das Jahr 2019 stand im Theatermuseum ganz im überdauert haben. Zusätzlich wurde eigens für Es ist immer jetzt Zeichen des Tanzes. Mit Alles tanzt. Kosmos Wiener dieses Ausstellungsprojekt ein umfangreiches Be- Tanzmoderne und Die Spitze tanzt. 150 Jahre Ballett gleit- und Vermittlungsprogramm entwickelt. an der Wiener Staatsoper waren gleich zwei Aus- Dazu zählte die abwechslungsreiche Reihe Bits stellungen diesem Thema gewidmet. and Pieces, für die Studierende der Musik und Kunst Privatuniversität (MUK) und TänzerInnen 2015 erfolgte die Übergabe des umfang reichen insgesamt 28 unterschiedliche Performances und schriftlichen Nachlasses der Tänzerin, Choreogra- Vorträge erarbeiteten und in den Schauräumen fin und Pädagogin Rosalia Chladek (Brünn 1905 – wie im Rest des Museums darboten. 1995 Wien) von der Internationalen Gesellschaft Rosalia Chladek an das neu gegründete Tanz-Ar- Parallel zur Tanzmoderne wurde in Kooperation mit chiv der Musik und Kunst Privatuniversität der dem Wiener Staatsballett ab Mai die Jubiläumsaus- Stadt Wien. Dieses Material wird seither unter der stellung Die Spitze tanzt. 150 Jahre Ballett an der Leitung der Tanzwissenschaftlerin und Kuratorin Wiener Staatsoper präsentiert. Dabei wurden in Andrea Amort in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Thea- mehreren Kapiteln Merkmale untersucht und vor- termuseum an der Privatuniversität aufgearbeitet. gestellt, die das Ballett-Ensemble von der Kaiser- Es soll nach dem Abschluss der Tätigkeiten unse- zeit über das 20. Jahrhundert bis zur unmittelbaren rem Haus übergeben werden und bildete schon Gegenwart geprägt haben. Thematisiert wurde jetzt den Ausgangspunkt zur ersten der beiden dabei auch das Schaffen wichtiger Persönlichkei- Ausstellungen, die im März eröffnet wurde. ten wie Josef Haßreiter, Gerhard Brunner, Rudolf Nurejew, Renato Zanella und Manuel Legris. -

Diplomarbeit

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Bücher sammeln aus Leidenschaft - Privatbibliotheken in Wien um 1900 VERFASSERIN Marlene Falmbigl ANGESTREBTER AKADEMISCHER GRAD: Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil) Wien, 2009 STUDIENKENNZAHL LT. STUDIENPLAN: A 332 STUDIENRICHTUNG LT. STUDIENPLAN: DEUTSCHE PHILOLOGIE BETREUER: AO. UNIV.-PROF. DR. MURRAY G. HALL VORWORT An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich bei meinen Eltern bedanken, die mir das Studium durch ihre finanzielle Unterstützung ermöglicht haben. Außerdem danke ich allen Mitarbeitern der Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, im Besonderen Herrn Mag. Buchberger, der mich vor allem bei der Themenfindung inspiriert hat und mir immer seine Hilfe angeboten hat. Für die Unterstützung und die hilfreichen Literaturhinweise bedanke ich mich bei meinem Betreuer Professor Dr. M. G. Hall. 1 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS EINLEITUNG...............................................................................................................5 1. FORSCHUNGSSTAND UND METHODE ...............................................................9 2. POLITISCHE SITUATION IN WIEN UM 1900.......................................................10 2.1. KAISER FRANZ JOSEPH UND DER UNTERGANG DER MONARCHIE ........................... 10 2.2. VON LIBERAL ZU „NATIONAL “ – NEUE POLITISCHE BEWEGUNGEN ............................ 11 3. WIENER KULTUR UND GESELLSCHAFT IM FIN DE SIÈCLE............................13 3.1. HOCHBLÜTE ALS RESULTAT POLITISCHER REPRESSIVITÄT .................................... 14 3.2. POLARITÄTEN UND KRISENSTIMMUNG ALS MOTOR -

SERIES V CRITICISM Box Folder 32 Max Reinhardt Directed Plays 1

SERIES V CRITICISM Box Folder 32 Max Reinhardt directed plays 1 Overview 2 1914 W. Schmidtbonn Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1914 Director: Max Reinhardt 3 Abschied vom Regiment and Angele O. E. Hartleben Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1905 Director: Richard Vallentin 4 Ackermann F. Hollaender and L. Schmidt Kleines Theater (Schall und Rauch); 1902 Director: Richard Vallentin 5 Bunbury. O. Wilde Kleines Theater / Neues Theater, Berlin; 1902/1903 Director: Hans Oberländer see Box 31, Folder 66. Salome 6 Candida G. B. Shaw Neues Theater, Berlin; 1904 Director: Felix Hollaender 7 Don Carlos F. v. Schiller Deutsches Theater, Berlin; 1917 Director: Max Reinhardt 8 Die Doppelgänger-Komödie A. Paul Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1904 Director: Richard Vallentin 9 Doppelselbstmord L. Anzengruber Neues Theater, Berlin; 1903 Director: Richard Vallentin 10 Dorothea Angermann G. Hauptmann Theater in der Josefstadt, Vienna; 1926 Director: Max Reinhardt 11 Einen Jux will er sich machen J. Nestroy Neues Theater, Berlin; 1904 Director: Max Reinhardt 12 Elektra H. v. Hofmannsthal (based on Sophokles) Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1903 Director: Max Reinhardt 13 Erdgeist F. Wedekind Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1902 Director: Richard Vallentin 14 Erdgeist F. Wedekind Neues Theater, Berlin; 1904 Director: Richard Vallentin 15 The Eternal Road F. Werfel Manhattan Opera House, New York; 1937 Director: Max Reinhardt 16 Faust J. W. v. Goethe Salzburg Festival (Festspielhaus); 1933 Director: Max Reinhardt 17 Faust J. W. v. Goethe Pilgrimage Outdoor Theatre, LA; 1938 Director: Max Reinhardt 18 Die Fledermaus J. Strauss Théâtre Pigalle, Paris; 1933 Director: Max Reinhardt 19 Fräulein Julie A. Strindberg Kleines Theater, Berlin; 1904 Director: Richard Vallentin 20 Früchte der Bildung L.