Complete Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CLoK The North of England in British Wartime Film, 1941 to 1946. Alan Hughes, University of Central Lancashire The North of England is a place-myth as much as a material reality. Conceptually it exists as the location where the economic, political, sociological, as well as climatological and geomorphological, phenomena particular to the region are reified into a set of socio-cultural qualities that serve to define it as different to conceptualisations of England and ‘Englishness’. Whilst the abstract nature of such a construction means that the geographical boundaries of the North are implicitly ill-defined, for ease of reference, and to maintain objectivity in defining individual texts as Northern films, this paper will adhere to the notion of a ‘seven county North’ (i.e. the pre-1974 counties of Cumberland, Westmorland, Northumberland, County Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire) that is increasingly being used as the geographical template for the North of England within social and cultural history.1 The British film industry in 1941 As 1940 drew to a close in Britain any memories of the phoney war of the spring of that year were likely to seem but distant recollections of a bygone age long dispersed by the brutal realities of the conflict. Outside of the immediate theatres of conflict the domestic industries that had catered for the demands of an increasingly affluent and consuming population were orientated towards the needs of a war economy as plant, machinery, and labour shifted into war production. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL (Neo-)Victorian

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL (Neo-)Victorian Impersonations: 19th Century Transvestism in Contemporary Literature and Culture being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD in the University of Hull by Allison Jayne Neal, BA (Hons), MA September 2012 Contents Contents 1 Acknowledgements 3 List of Illustrations 4 List of Abbreviations 6 Introduction 7 Transvestites in History 19th-21st Century Sexological/Gender Theory Judith Butler, Performativity, and Drag Neo-Victorian Impersonations Thesis Structure Chapter 1: James Barry in Biography and Biofiction 52 ‘I shall have to invent a love affair’: Olga Racster and Jessica Grove’s Dr. James Barry: Her Secret Life ‘Betwixt and Between’: Rachel Holmes’s Scanty Particulars: The Life of Dr James Barry ‘Swaying in the limbo between the safe worlds of either sweet ribbons or breeches’: Patricia Duncker’s James Miranda Barry Conclusion: Biohazards Chapter 2: Class and Race Acts: Dichotomies and Complexities 112 ‘Massa’ and the ‘Drudge’: Hannah Cullwick’s Acts of Class Venus in the Afterlife: Sara Baartman’s Acts of Race Conclusion: (Re)Commodified Similarities Chapter 3: Performing the Performance of Gender 176 ‘Let’s perambulate upon the stage’: Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem ‘All performers dress to suit their stages’: Tipping the Velvet ‘It’s only human nature after all’: Tipping the Velvet and Adaptation 1 Conclusion: ‘All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players’ Chapter 4: Cross-Dressing and the Crisis of Sexuality 239 ‘Your costume does not lend itself to verbal declarations’: -

On the Disability Aesthetics of Music,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 69, No

Published as “On the Disability Aesthetics of Music,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 69, no. 2 (2016): 525–63. © 2016 by the ReGents of the University of California. Copying and permissions notice: Authorization to copy this content beyond fair use (as specified in Sections 107 and 108 of the U. S. CopyriGht Law) for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is Granted by the ReGents of the University of California for libraries and other users, provided they are reGistered with and pay the specified fee via RiGhtslink® or directly with the CopyriGht Clearance Center. Colloquy On the Disability Aesthetics of Music BLAKE HOWE and STEPHANIE JENSEN-MOULTON, Convenors in memoriam Tobin Siebers Contents Introduction 525 BLAKE HOWE and STEPHANIE JENSEN-MOULTON Modernist Music and the Representation of Disability 530 JOSEPH N. STRAUS Sounding Traumatized Bodies 536 JENNIFER IVERSON Singing beyond Hearing 542 JESSICA A. HOLMES Music, Autism, and Disability Aesthetics 548 MICHAEL B. BAKAN No Musicking about Us without Us! 553 ANDREW DELL’ANTONIO and ELIZABETH J. GRACE Works Cited 559 Introduction BLAKE HOWE and STEPHANIE JENSEN-MOULTON Questions Drawing on diverse interdisciplinary perspectives (encompassing literature, history, sociology, visual art, and, more recently, music), the field of disability studies offers a sociopolitical analysis of disability, focusing on its social Early versions of the essays in this colloquy were presented at the session “Recasting Music: Mind, Body, Ability” sponsored by the Music and DisabilityStudyandInterestGroupsatthe annual meetings of the American Musicological Society and Society for Music Theory in Milwaukee, WI, November 2014. Tobin Siebers joined us a respondent, generously sharing his provocative and compelling insights. -

Britain's Best Recruiting Sergeant

BRITAIN’S BEST RECRUITING SERGEANT TEACHER RESOURCE PACK FOR TEACHERS WORKING WITH PUPILS IN YEAR 3 – 6 BRITAIN’S BEST RECRUITING SERGEANT RUNNING FROM 13 FEB - 15 MAR 2015 WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO BE A MAN? Little Tilley’s dreams are realised as she follows in her father’s footsteps and grows up to become Vesta Tilley, a shining star of the music hall whose much-loved act as a male impersonator makes her world-famous. War breaks out and she supports the cause by helping to recruit soldiers to fight for king and country, but has she used her stardom for good? And is winning the most important thing? The Unicorn commemorates the centenary of World War One and the 150th anniversary of Vesta Tilley’s birth in this feisty, song-filled and touching look at the life of Vesta Tilley (1864 – 1952), who was nicknamed Britain’s Best Recruiting Sergeant and led the way for female stars in music hall entertainment. Page 2 BRITAIN’S BEST RECRUITING SERGEANT CONTENTS CONTEXT INTRODUCTION 4 A SUMMARY OF THE PLAY 5 THE PLAY IN CONTEXT 7 INTERVIEWS WITH THE CREATIVE TEAM 9 CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES PRE-SHOW WORK 1. MUSIC HALL ACTS - STOP AND SHOW 13 2. CREATING MUSIC HALL ACTS 15 3. PUBLICITY POSTCARDS 17 4. PRESENTING! CREATING THE COMPERE 18 5. A NIGHT AT THE MUSIC HALL 20 6. CAN I ASK YOU SOMETHING? 21 7. HERE’S MY ADVICE - WRITING TO VESTA/HARRY 23 POST-SHOW WORK 1. FIVE MOMENTS 24 2. WHAT MADE THE PLAY MEMORABLE FOR YOU? 25 3. -

Pracy Family History from Tudor Times to the 1920S

Pracy family history: the origins, growth and scattering of a Wiltshire and East London family from Tudor times to the 1920s, 5th edition (illustrated) by David Pracy (b. 1946) List of illustrations and captions ..................................................................................... 2 Note: what’s new ............................................................................................................ 5 Part 1: Wiltshire ............................................................................................................. 6 1. Presseys, Precys and Pracys ................................................................................... 7 2. Bishopstone ............................................................................................................ 8 3. The early Precys ................................................................................................... 11 4. The two Samuels .................................................................................................. 15 5. The decline of the Precys in Bishopstone ............................................................ 20 Part 2: The move to London ......................................................................................... 23 6. Edward Prascey (1707-1780) and his sister Elizabeth’s descendants .................. 23 7. Three London apprentices and their families........................................................ 34 8. Edmund the baker (1705-1763) and his family .................................................. -

Lazarsfeld AJVS Final-Layout

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online The English Warner Brother triumphs over religious hegemony on the road to celebrity and dynasty Ann Lazarsfeld-Jensen In late Victorian England, music halls were often besieged by fanatical Christians who wanted to shut them down. Evangelicals manipulated justifiable public concerns about alcohol abuse to conflate popular entertainment with social erosion. The complex legislation surrounding places of entertainment began in the 1830s with concerns about limelight and sawdust, but by the 1880s it was firmly focused on morality (Victorian Music Halls 63) The music hall wars were an alarming threat for the predominantly Jewish artists and hall managers barely one generation beyond refugee poverty. It was unwise for them to oppose anything rooted in the national religious hegemonies, and they could not find a moral high ground to protect their livelihood. In this context, the fin de siècle Jewish theatrical agent, Dick Warner, began to use networks of men’s clubs and newspaper publicity to redefine the industry. The peaceful assimilation of Jews with its concomitant benefits for the pursuit of profit (Jews of Britain 77-79) was not a cynical ambition. Warner subscribed to the Victorian Anglo-Jewish world view of judicious assimilation and restrained observance, and he embraced it as the way forward for theatrical entrepreneurs who were losing ground to what Kift refers to as the “sour-faced, austere and ascetic” social reformers (157). The themes of Warner’s publicity campaign are recognisable today. -

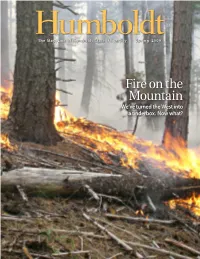

Fire on the Mountain We’Ve Turned the West Into a Tinderbox

The Magazine of Humboldt State University | Spring 2009 Fire on the Mountain We’ve turned the West into a tinderbox. Now what? humboldt.edu/magazine Humboldt Magazine is published twice a year for alumni and friends of Humboldt State University and is produced by University Advancement. The opinions expressed on these pages do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the university administration or those of the California State University Board of Trustees. President Rollin Richmond Vice President for University Advancement Robert Gunsalus Associate Vice President for Marketing & Communications Frank Whitlatch Editor Allison Monro Graphic Design ON THE COVER: A controlled burn southeast of Willow Creek, Calif. Called a “jackpot burn” Hugh Dalton, Kristen Stegeman-Gould, because it targets fuel concentrations, this burn reduced fuels left over from a tree harvest. Connie Webb, Benjamin Schedler Photo courtesy of James Arciniega. Photography Kellie Jo Brown Background Photo: Marching straight into the ocean? It’s just another day for the Writing Marching Lumberjacks, who celebrated 40 years of irreverence this year. David Lawlor, Paul Mann, Jarad Petroske Interns Jessica Lamm, Jocelyn Orr Alumni Association alumni.humboldt.edu 707.826.3132 Submit Class Notes to the alumni website or [email protected] Letters are welcome and may be published in upcoming issues of Humboldt. Humboldt Magazine Marketing & Communications 1 Harpst Street, Arcata, CA 95521 [email protected] The paper for Humboldt Magazine comes from responsibly managed sources, contains 10 percent post-consumer recycled content and is Forest Stewardship Council certified. From the President 2 Spring09 News in Brief 3 Holly Hosterman and Paul “Yashi” Lubitz 12 From garage workshop to global design. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Sujet E3C N°03827 Du Bac LVA Et LVB Allemand Première T3

ÉPREUVES COMMUNES DE CONTRÔLE CONTINU CLASSE : Première VOIE : ☐ Générale ☐ Technologique ☒ Toutes voies (LV) ENSEIGNEMENT : LV allemand DURÉE DE L’ÉPREUVE : 1h30 Niveaux visés (LV) : LVA B1-B2 LVB A2-B1 Axe de programme :1 CALCULATRICE AUTORISÉE : ☐Oui ☒ Non DICTIONNAIRE AUTORISÉ : ☐Oui ☒ Non ☐ Ce sujet contient des parties à rendre par le candidat avec sa copie. De ce fait, il ne peut être dupliqué et doit être imprimé pour chaque candidat afin d’assurer ensuite sa bonne numérisation. ☐ Ce sujet intègre des éléments en couleur. S’il est choisi par l’équipe pédagogique, il est nécessaire que chaque élève dispose d’une impression en couleur. ☐ Ce sujet contient des pièces jointes de type audio ou vidéo qu’il faudra télécharger et jouer le jour de l’épreuve. Nombre total de pages : 5 1/5 C1CALLE03827 SUJET LANGUES VIVANTES : ALLEMAND EVALUATION 2 Compréhension de l’écrit et expression écrite Niveaux visés Durée de l’épreuve Barème : 20 points LVA: B1-B2 CE: 10 points LVB: A2-B1 1h30 EE: 10 points L’ensemble du sujet porte sur l’axe 1 du programme : Identités et échanges Il s’organise en deux parties : 1- Compréhension de l’écrit 2- Expression écrite Vous disposez tout d’abord de cinq minutes pour prendre connaissance de l’intégralité du dossier. Vous organiserez votre temps comme vous le souhaitez pour rendre compte en allemand du document écrit (en suivant les indications données ci-dessous – partie 1) et pour traiter en allemand le sujet d’expression écrite (partie 2). Titre du document : Alte Heimat, neue Heimat 1. Compréhension de l'écrit a) Texte A und B: Lesen Sie beide Texte. -

Genre Bending Narrative, VALHALLA Tells the Tale of One Man’S Search for Satisfaction, Understanding, and Love in Some of the Deepest Snows on Earth

62 Years The last time Ken Brower traveled down the Yampa River in Northwest Colorado was with his father, David Brower, in 1952. This was the year his father became the first executive director of the Sierra Club and joined the fight against a pair of proposed dams on the Green River in Northwest Colorado. The dams would have flooded the canyons of the Green and its tributary, Yampa, inundating the heart of Dinosaur National Monument. With a conservation campaign that included a book, magazine articles, a film, a traveling slideshow, grassroots organizing, river trips and lobbying, David Brower and the Sierra Club ultimately won the fight ushering in a period many consider the dawn of modern environmentalism. 62 years later, Ken revisited the Yampa & Green Rivers to reflect on his father's work, their 1952 river trip, and how we will confront the looming water crisis in the American West. 9 Minutes. Filmmaker: Logan Bockrath 2010 Brower Youth Awards Six beautiful films highlight the activism of The Earth Island Institute’s 2011 Brower Youth Award winners, today’s most visionary and strategic young environmentalists. Meet Girl Scouts Rhiannon Tomtishen and Madison Vorva, 15 and 16, who are winning their fight to green Girl Scout cookies; Victor Davila, 17, who is teaching environmental education through skateboarding; Alex Epstein and Tania Pulido, 20 and 21, who bring urban communities together through gardening; Junior Walk, 21 who is challenging the coal industry in his own community, and Kyle Thiermann, 21, whose surf videos have created millions of dollars in environmentally responsible investments. -

Request a Printed Copy

Request a printed copy SKU Title 100 DAYS BEFORE THE COMMAND (Sto Dney do Prikaza) (1991) * with switchable 5989 English and German subtitles * 1858 12 MINUTEN NACH 12 (1939) 590 13 MANN UND EINE KANONE (1938) 3098 1860 (1934) * with switchable English subtitles * 776 1914 - DIE LETZTEN TAGE VOR DEM WELTBRAND (1931) * improved picture quality * 5290 1922 (1978) * with switchable English subtitles * 2554 24 STUNDEN AUS DEM LEBEN EINER FRAU (1931) * with switchable English subtitles * 1864 4 TREPPEN RECHTS (1945) 5697 491 (1964) * with switchable English and German subtitles * 356 5 FINGERS (1952) 681 A.D. – THE GLORY OF THE KHAN (1984) * with hard-encoded Bulgarian 2453 subtitles * 1857 7 OHRFEIGEN (1937) 4878 80 HUSZAR (80 Hussars) (1978) * with switchable English subtitles * 5505 A BAD JOKE (Skvernyy anekdot) (1966) * with switchable English subtitles * A BRIVELE DER MAMEN (A LETTER TO MAMA) (1938) *Hard-Encoded English 786 subtitles* 3056 A CANTERBURY TALE (1944) 5040 A CARRIAGE TO VIENNA (1966) * with switchable English subtitles * 4163 A COTTAGE ON DARTMOOR (1929) 3066 A DEADLY INVENTION (Vynález zkázy) (1958) 5575 A DREAM (1964) * with switchable English subtitles * 2769 A FIRE HAS BEEN ARRANGED (1935) 319 A FOREIGN AFFAIR (1948) * with or without hard-encoded German subtitles * 2919 A GIRL IN BLACK (To koritsi me ta mavra) (1956) * with switchable English subtitles * 2590 A HISTORY OF MILITARY PARADES ON RED SQUARE (1918 – 2010) (2013) 312 A JOURNEY THROUGH OLD EAST PRUSSIA *with switchable English subtitles* 313 A JOURNEY THROUGH -

Music Hall, C

NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available NOTE TO USERS The cassette is not included in this original manuscript. It is available for consultation at the author's graduate school library. From the Provinces: The Representation of Regional Identity in the British Music Hall, c. 1880-1914 by Nicole Amanda Gocker A Thesis submitted to the Department in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Queen's University Kingston, Ontario, Canada June, 1998 O Nicole Amanda Crocker National Libtary Bibliothbque nationale 1+1 of,,, du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OFtawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lîbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or selI reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelfilm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othhse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son oennission.