THE UNIVERSITY of HULL (Neo-)Victorian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Detestable Offenses: an Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century”

“Detestable Offenses: An Examination of Sodomy Laws from Colonial America to the Nineteenth Century” Taylor Runquist Western Illinois University 1 The act of sodomy has a long history of illegality, beginning in England during the reign of Henry VIII in 1533. The view of sodomy as a crime was brought to British America by colonists and was recorded in newspapers and law books alike. Sodomy laws would continue to adapt and change after their initial creation in the colonial era, from a common law offense to a clearly defined criminal act. Sodomy laws were not meant to persecute homosexuals specifically; they were meant to prevent the moral corruption and degradation of society. The definition of homosexuality also continued to adapt and change as the laws changed. Although sodomites had been treated differently in America and England, being a sodomite had the same social effects for the persecuted individual in both countries. The study of homosexuals throughout history is a fairly young field, but those who attempt to study this topic are often faced with the same issues. There are not many historical accounts from homosexuals themselves. This lack of sources can be attributed to their writings being censored, destroyed, or simply not withstanding the test of time. Another problem faced by historians of homosexuality is that a clear identity for homosexuals did not exist until the early 1900s. There are two approaches to trying to handle this lack of identity: the first is to only treat sodomy as an act and not an identity and the other is to attempt to create a homosexual identity for those convicted of sodomy. -

Models of Time Travel

MODELS OF TIME TRAVEL A COMPARATIVE STUDY USING FILMS Guy Roland Micklethwait A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University July 2012 National Centre for the Public Awareness of Science ANU College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences APPENDIX I: FILMS REVIEWED Each of the following film reviews has been reduced to two pages. The first page of each of each review is objective; it includes factual information about the film and a synopsis not of the plot, but of how temporal phenomena were treated in the plot. The second page of the review is subjective; it includes the genre where I placed the film, my general comments and then a brief discussion about which model of time I felt was being used and why. It finishes with a diagrammatic representation of the timeline used in the film. Note that if a film has only one diagram, it is because the different journeys are using the same model of time in the same way. Sometimes several journeys are made. The present moment on any timeline is always taken at the start point of the first time travel journey, which is placed at the origin of the graph. The blue lines with arrows show where the time traveller’s trip began and ended. They can also be used to show how information is transmitted from one point on the timeline to another. When choosing a model of time for a particular film, I am not looking at what happened in the plot, but rather the type of timeline used in the film to describe the possible outcomes, as opposed to what happened. -

Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 3-24-2016 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Barry, Todd, "From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 1041. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1041 From Wilde to Obergefell: Gay Legal Theatre, 1895-2015 Todd Barry, PhD University of Connecticut, 2016 This dissertation examines how theatre and law have worked together to produce and regulate gay male lives since the 1895 Oscar Wilde trials. I use the term “gay legal theatre” to label an interdisciplinary body of texts and performances that include legal trials and theatrical productions. Since the Wilde trials, gay legal theatre has entrenched conceptions of gay men in transatlantic culture and influenced the laws governing gay lives and same-sex activity. I explore crucial moments in the history of this unique genre: the Wilde trials; the British theatrical productions performed on the cusp of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act; mainstream gay American theatre in the period preceding the Stonewall Riots and during the AIDS crisis; and finally, the contemporary same-sex marriage debate and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The study shows that gay drama has always been in part a legal drama, and legal trials involving gay and lesbian lives have often been infused with crucial theatrical elements in order to legitimize legal gains for LGBT people. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

The Ladder March

MARCH THE LADDER 1 9 6 4 A Lesbian Review For Sale To Adults Only 50 cents In This Issue: Dr. James Barry, The First Woman Doctor in Britain March 1964 purpose off the t h e L addêX Voluae 8 Ifunber 6 Published monthly by tho Daughteri of Bflltls, Inc., o rton- 0^ BILITIS piollf corporation, 1232 Morhot Street, Suite 108, Son Fron- clico 2, California. Telephone: UNderhlll 3 _ 8196. A WOMEN’S ORGANIZATION FOR THE PURPOSE OP PROMOTING NATIONAL OFFICERS, DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS, INC. THE INTEGRATION OP THE HOMOSEXUAL INTO SOCIETY BY; ....... President-----Cleo Glenn Recording Secretary— Margaret Hetn2 Corresponding Secretary— Barbara GUtings .......... Public Relations Director— Meredith Grey ...... Treasi/fer— Ev Howe THE LADDER STAFF Editor— Barbara Gittings O Education of the variant, with particular emphasis on the psych Fiction and Poetry Editor^Agstha Machys Art Editor— Kathy Rogers ological, physiological and sociological aspects, to enable her Los Angeles Reporter— Sten Russell to understand herself and make her adjustment to society in all Chicago Reporter— Sand Production— Joan Oliver, V e Pigrom its social, civic and economic implications— this to be accomp Circulation Manager~—C\co Glenn lished by establishing and maintaining as complete a library as possible of both fiction and non-fiction literature on the sex de THE LADDER is ra9ard«d as a sounding board for various viant theme; by sponsoring public discussions on pertinent sub points of view on th# homophila and related subjects and jects to be conducted by leading members of the legal, psychiat does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the organiiation. -

The Cottonwool Doctor the Story of Margaret Ann Bulkly, Known As Dr James Barry

Jean de Wet Michelle Matthews Bridgitte Chemaly Potton Margaret was clever and curious. Margaret had big dreams. But 200 years ago a girl could not become a doctor. So she cut off her hair and she put on boy’s clothes. From then onwards, no one knew that Margaret was a girl. She became James Barry. TheThe CottonwoolCottonwool DoctorDoctor The story of Margaret Ann Bulkly, known as Dr James Barry The Cottonwool Doctor The story of Margaret Ann Bulkly, known as Dr James Barry This book belongs to Every child should own a hundred books by the age of five. To that end, Book Dash gathers creative professionals who volunteer to create new, African storybooks that anyone can freely translate and distribute. To find out more, and to download beautiful, print-ready books, visit bookdash.org. The Cottonwool Doctor: The story of Margaret Ann Bulkly, known as Dr James Barry Illustrated by Jean de Wet Written by Michelle Matthews Designed by Bridgitte Chemaly Potton with the help of the Book Dash participants in Cape Town on 10 May 2014. ISBN: 978-0-9946519-5-2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/). You are free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) and adapt (remix, transform, and build upon the material) this work for any purpose, even commercially. The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the following license terms: Attribution: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. -

The Performance of Gender with Particular Reference to the Plays of Shakespeare

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Dixon, Luke (1998) The performance of gender with particular reference to the plays of Shakespeare. PhD thesis, Middlesex University. [Thesis] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/6384/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

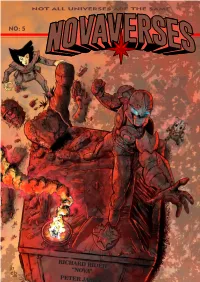

NOVAVERSES ISSUE 5D

NOT ALL UNIVERSES ARE THE SAME NO: 5 NOT ALL UNIVERSES ARE THE SAME RISE OF THE CORPS Arc 1: Whatever Happened to Richard Rider? Part 1 WRITER - GORDON FERNANDEZ ILLUSTRATION - JASON HEICHEL and DAZ RED DRAGON PART 3 WRITER - BRYAN DYKE ILLUSTRATION - FERNANDO ARGÜELLO STARSCREAM PART 5 WRITER - DAZ BLACKBURN ILLUSTRATION - EMILIANO CORREA, JOE SINGLETON and DAZ DREAM OF LIVING JUSTICE PART 2 WRITER - BYRON BREWER ILLUSTRATION - JASON HEICHEL Edited by Daz Blackburn, Doug Smith & Byron Brewer Front Cover by JASON HEICHEL and DAZ BLACKBURN Next Cover by JOHN GARRETSON Novaverses logo designed by CHRIS ANDERSON NOVA AND RELATED MARVEL CHARACTERS ARE DULY RECOGNIZED AS PROPERTY AND COPYRIGHT OF MARVEL COMICS AND MARVEL CHARACTERS INC. FANS PRODUCING NOVAVERSES DULY RECOGNIZE THE ABOVE AND DENOTE THAT NOVAVERSES IS A FAN-FICTION ANTHOLOGY PRODUCED BY FANS OF NOVA AND MARVEL COSMIC VIA NOVA PRIME PAGE AND TEAM619 FACEBOOK GROUP. NOVAVERSES IS A NON-PROFIT MAKING VENTURE AND IS INTENDED PURELY FOR THE ENJOYMENT OF FANS WITH ALL RESPECT DUE TO MARVEL. NOVAVERSES IS KINDLY HOSTED BY NOVA PRIME PAGE! ORIGINAL CHARACTERS CREATED FOR NOVAVERSES ARE THE PSYCHOLOGICAL COSMIC CONSTANT OF INDIVIDUAL CREATORS AND THEIR CENTURION IMAGINATIONS. DOWNLOAD A PDF VERSION AT www.novaprimepage.com/619.asp READ ONLINE AT novaprime.deviantart.com Rise of the Nova Corps obert Rider walked somberly through the city. It was a dark, bleak, night, and there weren't many people left on the streets. His parents and friends all warned him about the dangers of 1 Rwalking in this neighborhood, especially at this hour, but Robert didn't care. -

Hetherington, K

KRISTINA HETHERINGTON Editor Feature Films: THE DUKE - Sony/Neon Films - Roger Michell, director BLACKBIRD - Millennium Films - Roger Michell, director Toronto International Film Festival, World Premiere RED JOAN - Lionsgate - Trevor Nunn, director Toronto International Film Festival, Official Selection CHRISTOPHER ROBIN (additional editor) - Disney - Marc Forster, director MY COUSIN RACHEL - Fox Searchlight Pictures - Roger Michell, director DETOUR - Magnet Releasing - Christopher Smith, director TRESPASS AGAINST US - A24 - Adam Smith, director LE WEEK-END - Music Box Films - Roger Michell, director JAPAN IN A DAY - GAGA - Philip Martin & Gaku Narita, directors A BOY CALLED DAD - Emerging Pictures - Brian Percival, director SUMMER - Vertigo Films - Kenny Glenaan, director YASMIN - Asian Crush - Kenny Glenaan, director BLIND FIGHT - Film1 - John Furse, director LIAM - Lions Gate Films - Stephen Frears, director Television: SITTING IN LIMBO (movie) - BBC One/BBC - Stella Corradi, director THE CHILD IN TIME (movie) - BBC One/BBC - Julian Farino, director THE CROWN (series) - Netflix/Left Blank Pictures - Stephen Daldry & Philip Martin, directors MURDER (mini-series) - BBC/Touchpaper Television - Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard, directors BIRTHDAY (movie) - Sky Arts/Slam Films - Roger Michell, director THE LOST HONOUR OF CHRISTOPHER JEFFERIES - ITV/Carnival Film & TV - Roger Michell, director RTS of West England Award Winner, Best Editing in Drama KLONDIKE (mini-series) - Discovery Channel/Scott Free Productions - Simon Cellan Jones, director -

Inspector General James Barry MD: Putting the Woman in Her Place

MIDDLES BMJ: first published as 10.1136/bmj.298.6669.299 on 4 February 1989. Downloaded from Inspector General James Barry MD: putting the woman in her place Brian Hurwitz, Ruth Richardson James Barry qualified in medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1812, at the age of only 17. Barry's MD thesis, in Latin, was on hernia of the groin.' As its epigraph it had a quotation from the classical dramatist Menander, which urged the examiners: "Do not consider my youth, but whether I show a man's wisdom."2 No one spotted the real meaning of these words, and Barry proceeded to walk the wards as a pupil dresser at the United Hospitals of Guy's and St Thomas's under the tutelage of Astley Cooper. In January 1813 Dr Barry was "examined and passed as a Regimental Surgeon" by the Royal College of Surgeons of London.3 Thus began a career that was to span almost halfa century and take in halfthe globe and was to culminate in the rank of inspector general of hospitals in the British army.4 A revelation James Barry's life and career have since provided inspiration for several literary works, including bio- graphies,35 at least four novels,6'0 and two plays." 12 The cause of this interest is not difficult to find. This "most skilful of physicians, and ... most wayward of men"'3 died at 14 Margaret Street, Marylebone, during the summer of 1865. Shortly afterwards the following http://www.bmj.com/ report appeared in the Manchester Guardian'4: An incident is just now being discussed in military circles so extraordinary that, were not the truth capable of being vouched for by official authority, the narration would certainly be deemed absolutely incredible. -

Thorragnarok59d97e5bd2b22.Pdf

©2017 Marvel. All Rights Reserved. CAST Thor . .CHRIS HEMSWORTH Loki . TOM HIDDLESTON Hela . CATE BLANCHETT Heimdall . .IDRIS ELBA Grandmaster . JEFF GOLDBLUM MARVEL STUDIOS Valkyrie . TESSA THOMPSON presents Skurge . .KARL URBAN Bruce Banner/Hulk . MARK RUFFALO Odin . .ANTHONY HOPKINS Doctor Strange . BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Korg . TAIKA WAITITI Topaz . RACHEL HOUSE Surtur . CLANCY BROWN Hogun . TADANOBU ASANO Volstagg . RAY STEVENSON Fandral . ZACHARY LEVI Asgardian Date #1 . GEORGIA BLIZZARD Asgardian Date #2 . AMALI GOLDEN Actor Sif . CHARLOTTE NICDAO Odin’s Assistant . ASHLEY RICARDO College Girl #1 . .SHALOM BRUNE-FRANKLIN Directed by . TAIKA WAITITI College Girl #2 . TAYLOR HEMSWORTH Written by . ERIC PEARSON Lead Scrapper . COHEN HOLLOWAY and CRAIG KYLE Golden Lady #1 . ALIA SEROR O’NEIL & CHRISTOPHER L. YOST Golden Lady #2 . .SOPHIA LARYEA Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. Cousin Carlo . STEVEN OLIVER Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO Beerbot 5000 . HAMISH PARKINSON Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO Warden . JASPER BAGG Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM Asgardian Daughter . SKY CASTANHO Executive Producers . THOMAS M. HAMMEL Asgardian Mother . SHARI SEBBENS STAN LEE Asgardian Uncle . RICHARD GREEN Co-Producer . DAVID J. GRANT Asgardian Son . SOL CASTANHO Director of Photography . .JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE, ASC Valkyrie Sister #1 . JET TRANTER Production Designers . .DAN HENNAH Valkyrie Sister #2 . SAMANTHA HOPPER RA VINCENT Asgardian Woman . .ELOISE WINESTOCK Edited by . .JOEL NEGRON, ACE Asgardian Man . ROB MAYES ZENE BAKER, ACE Costume Designer . MAYES C. RUBEO Second Unit Director & Stunt Coordinator . BEN COOKE Visual Eff ects Supervisor . JAKE MORRISON Stunt Coordinator . .KYLE GARDINER Music by . MARK MOTHERSBAUGH Fight Coordinator . JON VALERA Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Head Stunt Rigger . ANDY OWEN Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Stunt Department Manager .