Longoni Modì Partial ENG 5-9-2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mario Puccini “Van Gogh Involontario” Livorno Museo Della Città 2 Luglio - 19 Settembre 2021

Mario Puccini “Van Gogh involontario” Livorno Museo della città 2 luglio - 19 settembre 2021 ELENCO DELLE OPERE GLI ESORDI E IL MAESTRO FATTORI Giovanni Fattori, Ritratto di contadina, 1880 circa, olio su tavola, 34x31 cm, Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori Livorno Silvestro Lega, Busto di contadina, 1872-1873, olio su tavola, 40x26 cm, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti, Firenze Mario Puccini, Ave Maria, 1887 circa, olio su tela, 69x42 cm, Istituto Matteucci, Viareggio Plinio Nomellini, Ritratto di signora, 1885 circa, olio su tela, 33x16 cm, collezione privata Mario Puccini, La modella (La fidanzata), 1889-1890, olio su tela, 49,6x26,6 cm, collezione Fondazione Livorno Plinio Nomellini, Signora in nero, 1887, olio su tela, 43x20 cm, collezione Giuliano Novelli Mario Puccini, Ritratto della fidanzata all’uscita dalla chiesa, olio su tela, 31x21 cm, collezione Rangoni Mario Puccini, Lupo di mare, olio su tela, 38,5x26,2 cm, collezione Rangoni Mario Puccini, Ritratto di giovane, 1890, olio su tela applicata a cartone, 35x25 cm, collezione Rangoni Mario Puccini, Autoritratto con colletto bianco, 1912, olio su tela, 31x21,8 cm, collezione Rangoni Mario Puccini, Interno del mio studio, olio su cartone, 44x28 cm, collezione Rangoni Mario Puccini, Autoritratto, 1914, 47x33 cm, collezione privata Mario Puccini, Autoritratto in controluce, 1914, olio su tavola, 38,5x32,8 cm, collezione privata, courtesy Società di Belle Arti, Viareggio Giovanni Fattori, Nel porto, 1890-1895, olio su tavola, 19x32 cm, Museo Civico Giovanni -

MARIO PUCCINI Con Il Patrocinio Di La Passione Del Colore Da Fattori Al Novecento

Mostra realizzata da MARIO PUCCINI Con il patrocinio di La passione del colore da Fattori al Novecento SERAVEZZA PALAZZO MEDICEO Con il contributo finanziario di PATRIMONIO MONDIALE UNESCO since 1821 11 luglio · 2 novembre 2015 Mostra a cura di Nadia Marchioni e Elisabetta Matteucci Palminteri 12 luglio · 6 settembre dal lunedì al venerdì 17 - 24 | sabato e domenica 10.30 - 12.30 e 17 - 24 Ufficio stampa Catalogo ILOGO, Prato Maschietto Editore 7 settembre · 2 novembre www.ilogo.it www.maschiettoeditore.com dal giovedì al sabato 15 - 20 | domenica 10.30 - 20 Ingresso intero 6.00 euro · ridotto 4.00 euro PONTE STAZZEMESE Biglietto famiglia: 12 euro (2 adulti con ragazzi fino a 14 anni) SERAVEZZA STRADA PROVINCIALE 9 STAZZEMA Ultimo ingresso 30 minuti prima dell’orario di chiusura. PALAZZO MEDICEO VIA SERAVEZZA Fondazione Terre Medicee STRADA PROVINCIALE 42 MARIO PUCCINI Palazzo Mediceo di Seravezza - Patrimonio Mondiale Unesco Viale L. Amadei, 230 (già Via del Palazzo) 55047 Seravezza LU VIA ALPI APUANE La passione del colore tel. 0584 757443 · [email protected] · www.palazzomediceo.it STRADA PROVINCIALE 8 Treno. Fermata di Forte dei Marmi · FORTE VIA AURELIA DEI MARMI Seravezza · Querceta da Fattori al Novecento Ufficio Informazioni Turistiche tel. 0584 757325 Collegamento con autobus di linea. [email protected] · www.prolocoseravezza.it Da Querceta per Seravezza: ogni ora PIETRASANTA VIA G.B. VICO A12 USCITA VERSILIA a partire dalle 6:55. Ultima corsa a 20:55 Visite guidate per singoli o gruppi: tutti i giovedì 21.00-22.30. Su prenotazione. (fermata Piazza Alessandrini, di fronte SERAVEZZA Disponibili su prenotazione anche in giorni diversi durante l’orario di apertura alla stazione ferroviaria). -

Visita Alla Casa Natale Di Modigliani

Visita alla Casa natale di Modigliani Sabato 12 aprile, alle ore 17, è in programma una visita guidata alla Casa natale di Amedeo Modigliani in Via Roma, 38 a Livorno. La famosa casa di via Roma, che per una serie di circostanze fortuite non è stata modificata, conserva an- cora tutto il fascino vintage di un appartamento della borghesia livornese all’indomani dell’Unità d’Italia, con i suoi pavi- menti in graniglia a motivi floreali, i suoi vetri sottili, la vecchia cucina con il lavello in marmo bianco e le dispense in mu- ratura. Questa è la casa dove è nato Dedo, ormai 130 anni fa, e dove ha iniziato i primi esperimenti artistici. E’ allestita come un museo con riproduzioni di vecchie foto e documenti della famiglia Modigliani, che ci aiutano a ricostruire la vita del pittore, dalla nascita “assistita da un ufficiale giudiziario” ai suoi legami con la città, la vita parigina, gli amori, gli amici, e la morte tragica a soli 36 anni. A Livorno Amedeo frequenta il Ginnasio Guerrazzi, in via Ernesto Rossi, a pochi passi da casa, ma in seguito a problemi di salute abbandona gli studi classici per andare a scuola da Guglielmo Micheli, dove conoscerà tantissimi ragazzi che presto diverran- no i suoi amici più cari: Gino Romiti, Oscar Ghiglia, Aristide Sommati, Benvenuto Benvenuti, Renato Natali, Llewelyn Lloyd, Manlio Martinelli, Lando Bartoli. Sabato 12 aprile sarà, quindi, l’occasione per trascorrere un bel pomeriggio di primavera a contatto con l’arte e la storia di Livorno, ma soprattutto per respirare il fascino di un ambi- ente ricco di emozioni, e ripercorrere la vita del livornese più amato e più famoso al mondo: Amedeo Modigliani. -

9-10 Ottobre 2017 FIRENZE

GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE FIRENZE GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE 9-10 Ottobre 2017 9-10 Ottobre ASTA 23 ASTA ASTA 23 LIBRI E GRAFICA PARTE I: Stampe, Disegni, Dipinti Via Ricasoli, 6-14/r | 50122 FIRENZE CASA D’ASTE tel +39 055 268279 fax +39 055 2396812 | www.gonnelli.it - [email protected] 9-10 Ottobre 2017 Gonnelli Casa d’Aste è un marchio registrato da Libreria Antiquaria Gonnelli FIRENZE GONNELLI Charta 153.qxp_[Gonnelli 195x280] 27/07/17 14:04 Pagina 1 GONNELLI CASA D’ASTE Via Ricasoli, 6-14/r | 50122 FIRENZE tel +39 055 268279 fax +39 055 2396812 www.gonnelli.it - [email protected] LEGENDA Ove non diversamente specificato tutti i testi (2): il numero fra parentesi dopo la descrizione del lotto indica la e le immagini appartengono a Gonnelli Casa quantità fisica dei beni che lo compongono. Ove non indicato si d’Aste, senza alcuna limitazione di tempo e di intende che il lotto è composto da un singolo bene. confini. Pertanto essi non possono essere ripro- dotti in alcun modo senza autorizzazione scritta Annibale Carracci: è nostra opinione che l’opera sia eseguita di Gonnelli Casa d’Aste. dall’Artista; Annibale Carracci [attribuito a]: è nostra opinione che l’opera sia probabilmente eseguita dall’Artista; Annibale Carracci In copertina particolare del lotto 967 [alla maniera di] [scuola di] [cerchia di]: l’opera per materiali, stile- mi, periodo e soggetti è accostabile alla scuola dell’Autore indicato; Annibale Carracci [da]: indica che l’opera è tratta da un originale riconosciuto dell’Autore indicato, ma eseguita da Autore diverso anche, eventualmente, in periodo diverso. -

Experiencing the Water Lands

TOSCANA Experiencing the water lands Livorno, Capraia Island and Collesalvetti between history, culture and tradition www.livornoexperience.com Livorno Experience Experiencing the water lands S E A R C H A N D S H A R E #livornoexperience livornoexperience.com IN PARTNERSHIP WITH S E A R C H A N D S H A R E #livornoexperience Information livornoexperience.com TOURIST INFORMATION OFFICES LIVORNO CAPRAIA ISLAND COLLESALVETTI INDICE Via Alessandro Pieroni, 18 Via Assunzione, Porto Sportello Unico per le Attività Ph. +39 0586 894236 (next to la Salata) Produttive e Turismo EXPERIENCING THE WATER LANDS PAG. 5 [email protected] Ph. +39 347 7714601 Piazza della Repubblica, 32 3 TRAVEL REASONS PAG. 8 www.turismo.li [email protected] Ph. +39 0586 980213 www.visitcapraia.it [email protected] LIVORNO PAG.10 www.comune.collesalvetti.li.it CAPRAIA ISLAND PAG. 30 COLLESALVETTI PAG. 42 EVENTS PAG. 50 HOW TO GET THERE BY CAR BY BUS Coming from Milan, you can take the A1 From Livorno Central Station, the main lines motorway, reaching Parma, and then take the leave to reach the city centre, “Lam Blu” which A15 motorway towards La Spezia and then the crosses the city centre and seafront, “Lam A12 towards Livorno, while from Rome you take Rossa” which crosses the city centre and arrives the A12 motorway, the section which connects at the hamlets of Montenero and Antignano. Rome to Civitavecchia, and then continue The urban Line 12 connects the city centre of along the Aurelia, now called E80, up to Livorno. -

Llewelyn Lloyd X INAT 2017

organizza una visita alla mostra accompagnati dalla curatrice Lucia Mannini sabato 25 novembre ore 15 Firenze - Palazzo Bardini PROGRAMMA DELL’INTERA GIORNATA I partecipanti possono arrivare con i propri mezzi a Firenze quando preferiscono, secondo le proprie esigenze. L’appuntamento per tutti i partecipanti è alle ORE 10 alla biglietteria di PALAZZO STROZZI per la visita alla mostra: Il Cinquecento a Firenze Dalle ore 12,30 alle 14,30 PRANZO in centro Dalle ore 15 alle ore 17,30 visita guidata alla Mostra di Lloyd a Villa Bardini Dalle ore 18 alle ore 20 tempo libero Dalle ore 20 alle ore 22,30 CENA facoltativa in centro I soci e i loro accompagnatori sono pregati di confermare la presenza appena possibile LA MOSTRA Il paesaggio è un tema sempre presente nell’opera pittorica di Lloyd, un artista apprezzato, sia per le sue rappresentazioni dell’Isola d’Elba, sia per le vedute fiorentine. Dalle albe rosate e dai tramonti infuocati del Divisionismo, in ampie raffigurazioni di campagne o affacci marini (di cui restano anche a documentazione alcuni grandi disegni a carboncino, anch’essi esposti nella mostra), si seguono, nelle sezioni successive della mostra, le nuove ricerche formali, impostate su rapporti cromatici e nuovi equilibri compositivi, culminando proprio nelle vedute del panorama fiorentino, cittadino e non: la selezione di queste opere dimostra come di fatto Lloyd possa essere considerato a pieno titolo tra i protagonisti del Novecento pittorico italiano. Curata da Lucia Mannini e promossa dalla Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio -

Oscar Ghiglia, Il Futuro Alle Spalle Hans Holbein Il Giovane E L

Minuti 386 nuovo.qxp_Layout 1 04/07/18 16:58 Pagina 1 n° 386 Oscar Ghiglia, il futuro alle spalle Hans Holbein il Giovane e l’astrazione del reale I cinque secoli di San Biagio Henri Matisse, regista dell’arte Il bianco, un nulla pieno di tutto n° 386 - luglio 2018 © Diritti riservati Fondazione Internazionale Menarini - vietata la riproduzione anche parziale dei testi e delle fotografie - Direttore Responsabile Lorenzo Gualtieri Redazione, corrispondenza: «Minuti» Edificio L - Strada 6 - Centro Direzionale Milanofiori I-20089 Rozzano (Milan, Italy) www.fondazione-menarini.it NOTEBOOK In the Farnese Family Horti On occasion of completion of the restoration of the Uccelliere on the Palatine, for the first time an exhi- bition recounts the history and secrets of the Farnese family’s Horti, one of the most celebrated sites of Re- naissance and Baroque Rome. The exhibition path winds through the sites where there once rose the gardens laid out by Car- dinal Alessandro Farnese in the mid-1500s. It begins with the plan for the geo- metric arrangement of the plantings in Italian formal garden style and continues with the season of the Grand Tour, when the gar- dens acquired that romantic air that so fascinated Goe- The Farnese Uccelliere (Aviaries) after the recent the, ending in the early restoration 20th century, when archa- eological research began. On show at the Uccelliere are two sculptures on loan from the Farnese collection at the National Archaeo- logical Museum of Naples and the two busts of Dacian prisoners which in the 17th century decorated the Nin- feo della Pioggia, designed by the Farneses, where mul- timedia installations recreate the original look of the Horti Farnesiani in im- mersive perspective and bird’s-eye views showing rows of trees, pergolas, and water features. -

Foglio1 Pagina 1

Foglio1 N. TITOLO AUTORI CASA EDITRICE ANNO 1 Modigliani Catalogue Raisonné J. Lanthemann Graficas Condal 1970 2 Amedeo Modigliani Catalogo Generale Dipinti Osvaldo Patani Leonardo Editore 1991 3 Amedeo Modigliani Catalogo Generale Sculture e Disegni Osvaldo Patani Leonardo Editore 1992 4 Amedeo Modigliani Catalogo Generale Sculture e Disegni copia Osvaldo Patani Leonardo Editore 1992 5 Modigliani Disegni Vol. 1 Osvaldo Patani Ed. Della Seggiola 1976 6 Modigliani Disegni Giovanili 1896/1905 Osvaldo Patani Alberindo Grimani Leonardo De Luca Editori 1990 7 Modigliani Catalogue Raisonné Christian Parisot Edizioni Carte Segrete 2006 8 Modigliani Catalogue Raisonné Christian Parisot Forma Edizioni 2012 9 Modigliani Nello Ponente Sadea/Sansoni Editori 1969 10 Modigliani Werner Schmalenbach Prestel / Verlag 1990 11 Modigliani Aldo Santini Ed. Rizzoli 1987 12 Modigliani Christian Parisot Edizioni Graphis Arte 1988 13 Modigliani Mostra Milano Palazzo reale Skira 2003 14 Amedeo Modigliani Alfred Werner Garzanti Editore 1990 15 Modigliani Stefano De Rosa Giunti 1997 16 Alberindo Grimani spiega l'opera di Amedeo Modigliani Alberindo Grimani Tribenet 2004 17 Amedeo Modigliani a Lugano Mostra Lugano Editoriale Giorgio Mondadori 1999 18 Modigliani l'ultimo romantico Corrado Augias Arnoldo Mondadori Editore 1998 19 Modigliani storia di un falso e di una grande beffa Gianni Farneti Arnoldo Mondadori Editore 1988 20 Amedeo Modigliani Principe di Montparnasse Herbert Lottman Jaca Book 2007 21 Modigliani Cento Capolavori al Vittoriano di Roma Mostra Roma -

Tuscany Travels Through Art

TUSCANY TRAVELS THROUGH ART Searching for beauty in the footsteps of great artists tuscany TRAVELS THROUGH ART Searching for beauty in the footsteps of great artists For the first time, a guide presents itineraries that let you discover the lives and works of the great artists who have made Tuscany unique. Architects, sculptors, painters, draughtsmen, inventors and unrivalled genius– es have claimed Tuscany as their native land, working at the service of famous patrons of the arts and leaving a heritage of unrivalled beauty throughout the territory. This guide is essential not only for readers approaching these famous names, ranging from Cimabue to Modigliani, for the first time, but also for those intent on enriching their knowledge of art through new discoveries. An innovative approach, a different way of exploring the art of Tuscany through places of inspiration and itineraries that offer a new look at the illustrious mas– ters who have left their mark on our history. IN THE ITINERARIES, SOME IMPORTANT PLACES IS PRESENTED ** DON’T MISS * INTERESTING EACH ARTIST’S MAIN FIELD OF ACTIVITY IS DISCUSSED ARCHITECT CERAMIST ENGINEER MATHEMATICIAN PAINTER SCIENTIST WRITER SCULPTOR Buon Voyage on your reading trip! Index of artists 4 Leona Battista Alberti 56 Caravaggio 116 Leonardo da Vinci 168 The Pollaiolo Brothers 6 Bartolomeo Ammannati 58 Galileo Chini 118 Filippo Lippi 170 Pontormo 8 Andrea del Castagno 62 Cimabue 120 Filippino Lippi 172 Raffaello Sanzio 10 Andrea del Sarto 64 Matteo Civitali 124 Ambrogio Lorenzetti 174 Antonio Rossellino -

Raccolta Dei Rifiuti Ingombranti E Raee Nel Comune Di Livorno Descrizione Zone Di Lavoro Zona 1

RACCOLTA DEI RIFIUTI INGOMBRANTI E RAEE NEL COMUNE DI LIVORNO DESCRIZIONE ZONE DI LAVORO ZONA 1 NOME TRATTO / DESCRIZIONE STRADA VIA DELLE ACCIUGHE VIA DEGLI AMMAZZATOI SCALI DELLE ANCORE VIA DELL' ANGIOLO VIA SANT' ANNA PIAZZA DELL' ARSENALE VIA DEGLI ASINI VIALE DEGLI AVVALORATI SCALI D' AZEGLIO VIA DEI BAGNETTI VIA DELLA BANCA VIA SANTA BARBARA SCALI DELLE BARCHETTE PIAZZA ILIO BARONTINI VIA ENRICO BARTELLONI VIA DEL BASTIONE PIAZZA ELIA BENAMOZEGH SCALI LUIGI BETTARINI VIA BORRA VIA FALCONE E BORSELLINO VIA BUIA VIA BUONTALENTI VIA CONTE LUIGI CADORNA VIA CAIROLI VIA CALAFATI VIALE CAPRERA VIA DEI CARABINIERI VIA DEL CARDINALE VIA CARRAIA VIA DEL CASINO VIA DARIO CASSUTO VIA SANTA CATERINA VIA DEL CAVALIERI PIAZZA FELICE CAVALLOTTI PIAZZA CAVOUR VIA GIUSEPPE CHIARINI VIA ENRICO CIALDINI LARGO DEL CISTERNINO VIA CLAUDIO COGORANO PIAZZA COLONNELLA VIA DELLE COMMEDIE VIA DELLA CORONCINA SCALI DEL CORSO VIA PIETRO COSSA VIA FRANCESCO CRISPI SCALI DELLA DARSENA VIA ARMANDO DIAZ PIAZZA DEI DOMENICANI LARGO DEL DUOMO VIA DELLA CINTA ESTERNA DA ORLANDO A PAMIGLIONE VIA DEI FANCIULLI VIA COSIMO DEL FANTE SCALI FINOCCHIETTI VIA FIUME VIA DEI FLORIDI VIA SANTA FORTUNATA VIA SAN FRANCESCO VIA DI FRANCO VIA DEI FULGIDI VIA DELLE GALERE VIA MONSIGNOR FILIPPO GANUCCI PIAZZA ANITA GARIBALDI VIA DEL GIGLIO VIA GIOVANNETTI VIA SAN GIOVANNI VIA SANTA GIULIA PIAZZA GRANDE VIA GRANDE VIA DELL'UFFIZIO DEI GRANI VIA MONTE GRAPPA PIAZZA GUERRAZZI SCALI DEGLI ISOLOTTI PIAZZA DELL' UNITA' D' ITALIA VIA DEI LANZI NOME TRATTO / DESCRIZIONE STRADA PIAZZA DEI LEGNAMI -

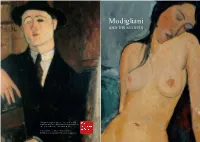

Modigliani and HIS MODELS

Modigliani AND HIS MODELS This guide is given out free to teachers and students with an exhibition ticket and student or teacher ID at the Education Desk. It is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £3.95 (while stocks last). INTRODUCTION Modigliani The funeral of Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris was attended by the elite and notorious of the Parisian art world, including Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Constantin AND HIS MODELS Brancusi (1876–1957) and André Derain (1880–1954), amongst hundreds of others. The price of Modigliani’s art increased tenfold Sackler Galleries 8 July–15 October 2006 almost overnight, and collectors reportedly solicited mourners for his paintings and drawings even as the cortège progressed along the funeral route. Montparnasse policemen, the very same who had repeatedly arrested him during his many nights of drunken and drug- An Introduction ‘I am … trying to formulate, addled debauchery, lined the streets of the procession, paying their to the Exhibition with the greatest lucidity, the respects to the dead artist and allegedly trying to acquire his work for for Teachers and Students truths of art and life I have themselves. Picasso remarked, not without irony, ‘Do you see? discovered scattered among Now he is avenged.’ Written by Lindsay Rothwell the beauties of Rome. As Only an extraordinary life and body of work could have produced Education Department their inner meaning becomes such fanfare and spectacle at its premature end. Stories abound about clear to me, I will seek to Modigliani’s excessive entanglement with women, drugs and alcohol, © Royal Academy of Arts reveal and to rearrange their and coupled with myriad posthumous written accounts of his life, they composition, in order to have created a mythology that makes separating the fiction from the create out of it my truth of fact of his life nearly impossible. -

Fondazione Cassa Di Risparmi Di Livorno 1992/2012 Nascita Di Una Collezione a Cura Di Stefania Fraddanni

Fondazione Cassa di Risparmi di Livorno 1992/2012 Nascita di una collezione a cura di Stefania Fraddanni Fondazione Cassa di Risparmi Pacini di Livorno Editore Fondazione Cassa di Risparmi di Livorno (1992/2012) © Copyright 2013 by Fondazione Cassa di Risparmi di Livorno Nascita di una collezione ISBN 978-88-6315-530-3 Chiusura delle iniziative promosse per il XX anniversario della nascita della Fondazione. Inaugurazione della sede ristrutturata e del nuovo ingresso. Realizzazione editoriale e grafica Apertura al pubblico dell’esposizione di opere d’arte. Livorno, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmi, Via A. Gherardesca Piazza Grande 23, 16 marzo 2013 56121 Ospedaletto (Pisa) www.pacinieditore.it 1992/2012 I venti anni della Fondazione [email protected] Responsabile Comunicazione Stefania Fraddanni Progetto Grafico Logo e Immagine Coordinata Anna Laura Bachini Sales Manager Beatrice Cambi Progetto editoriale a cura di Responsabile editoriale Stefania Fraddanni Elena Tangheroni Amatori con la collaborazione di Raffaella Soriani Direzione produzione Testi di Stefano Fabbri Andrea Baboni Giovanna Bacci di Capaci Conti Fotolito e Stampa Silvestra Bietoletti Industrie Grafiche Pacini Francesca Cagianelli Francesca Dini Vincenzo Farinella Referenze forografiche Piero Frati Archivio Dini, Montecatini-Firenze Francesca Giampaolo Fondo fotografico Istituto Matteucci, Viareggio Monica Guarraccino Archivio Baboni, già Malesci, Correggio Maria Teresa Lazzarini Nadia Marchioni Dario Matteoni Giuliano Matteucci L’editore resta a disposizione degli aventi diritto con i quali non è stato possibile comuni- Nicola Micieli care e per le eventuali omissioni. Renato Miracco Michele Pierleoni Le fotocopie per uso personale del lettore possono essere effettuate nei limiti del 15% di Sergio Rebora ciascun volume/fascicolo di periodico dietro pagamento alla SIAE del compenso previsto dall’art.