In the Matter of a Route Licensing Application Under

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

COVID-19) on Civil Aviation: Economic Impact Analysis

Effects of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) on Civil Aviation: Economic Impact Analysis Montréal, Canada 11 March 2020 Contents • Introduction and Background • Scenario Analysis: Mainland China • Scenario Analysis: Hong Kong SAR of China and Macao SAR of China • Summary of Scenario Analysis and Additional Estimates: China • Scenario Analysis: Republic of Korea • Scenario Analysis: Italy • Scenario Analysis: Iran (Islamic Republic of) • Preliminary Analysis: Japan and Singapore 2 Estimated impact on 4 States with the highest number of confirmed cases* Estimated impact of COVID-19 outbreak on scheduled international passenger traffic during 1Q 2020 compared to originally-planned: • China (including Hong Kong/Macao SARs): 42 to 43% seat capacity reduction, 24.8 to 28.1 million passenger reduction, USD 6.0 to 6.9 billion loss of gross operating revenues of airlines • Republic of Korea: 27% seat capacity reduction, 6.1 to 6.6 million passenger reduction, USD 1.3 to 1.4 billion loss of gross operating revenues of airlines • Italy: 19% seat capacity reduction, 4.8 to 5.4 million passenger reduction, USD 0.6 to 0.7 billion loss of gross operating revenues of airlines • Iran (Islamic Republic of): 25% seat capacity reduction, 580,000 to 630,000 passenger reduction, USD 92 to 100 million loss of gross operating revenues of airlines * Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report by WHO 3 Global capacity share of 4 States dropped from 23% in January to 9% in March 2020 • Number of seats offer by airlines for scheduled international passenger traffic; -

Hong Kong's Lost Right to Self-Determination: a Denial of Due Process in the United Nations

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 13 Number 1 Article 7 1992 HONG KONG'S LOST RIGHT TO SELF-DETERMINATION: A DENIAL OF DUE PROCESS IN THE UNITED NATIONS Patricia A. Dagati Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dagati, Patricia A. (1992) "HONG KONG'S LOST RIGHT TO SELF-DETERMINATION: A DENIAL OF DUE PROCESS IN THE UNITED NATIONS," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 13 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol13/iss1/ 7 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. HONG KONG'S LOST RIGHT TO SELF- DETERMINATION: A DENIAL OF DuE PROCESS IN THE UNITED NATIONS I. INTRODUCTION The end of the Cold War and the resolution of the Persian Gulf Crisis have enhanced the status of the United Nations from simply a forum for discussion to an international peacekeeping organization capable of coordinated action. In accord with its new role, the 46th United Nations General Assembly in September, 1991, welcomed seven new member states, whose admission would have been unthinkable during the days of the Cold War; namely, the two Koreas, the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and the two Pacific Island nations (previously Trusts under the U.N. Charter) of the Federated States of Micronesia and the Republic of the Marshall Islands.' One hopes that the entrance into the world community of these nations, so long deprived of their right to self- determination by the insecurities and suspicions of the Cold War, represents the end of the dominance of outmoded historical animosities and divisions over the right of a people to determine their own social, economic and political status. -

Attachment F – Participants in the Agreement

Revenue Accounting Manual B16 ATTACHMENT F – PARTICIPANTS IN THE AGREEMENT 1. TABULATION OF PARTICIPANTS 0B 475 BLUE AIR AIRLINE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS S.R.L. 1A A79 AMADEUS IT GROUP SA 1B A76 SABRE ASIA PACIFIC PTE. LTD. 1G A73 Travelport International Operations Limited 1S A01 SABRE INC. 2D 54 EASTERN AIRLINES, LLC 2I 156 STAR UP S.A. 2I 681 21 AIR LLC 2J 226 AIR BURKINA 2K 547 AEROLINEAS GALAPAGOS S.A. AEROGAL 2T 212 TIMBIS AIR SERVICES 2V 554 AMTRAK 3B 383 Transportes Interilhas de Cabo Verde, Sociedade Unipessoal, SA 3E 122 MULTI-AERO, INC. DBA AIR CHOICE ONE 3J 535 Jubba Airways Limited 3K 375 JETSTAR ASIA AIRWAYS PTE LTD 3L 049 AIR ARABIA ABDU DHABI 3M 449 SILVER AIRWAYS CORP. 3S 875 CAIRE DBA AIR ANTILLES EXPRESS 3U 876 SICHUAN AIRLINES CO. LTD. 3V 756 TNT AIRWAYS S.A. 3X 435 PREMIER TRANS AIRE INC. 4B 184 BOUTIQUE AIR, INC. 4C 035 AEROVIAS DE INTEGRACION REGIONAL 4L 174 LINEAS AEREAS SURAMERICANAS S.A. 4M 469 LAN ARGENTINA S.A. 4N 287 AIR NORTH CHARTER AND TRAINING LTD. 4O 837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. 4S 644 SOLAR CARGO, C.A. 4U 051 GERMANWINGS GMBH 4X 805 MERCURY AIR CARGO, INC. 4Z 749 SA AIRLINK 5C 700 C.A.L. CARGO AIRLINES LTD. 5J 203 CEBU PACIFIC AIR 5N 316 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY NORDAVIA - REGIONAL AIRLINES 5O 558 ASL AIRLINES FRANCE 5T 518 CANADIAN NORTH INC. 5U 911 TRANSPORTES AEREOS GUATEMALTECOS S.A. 5X 406 UPS 5Y 369 ATLAS AIR, INC. 50 Standard Agreement For SIS Participation – B16 5Z 225 CEMAIR (PTY) LTD. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

The Battle Over Democracy in Hong Kong, 19 N.C

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND COMMERCIAL REGULATION Volume 19 | Number 1 Article 6 Fall 1993 Envisioning Futures: The aB ttle veo r Democracy in Hong Kong Bryan A. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Bryan A. Gregory, Envisioning Futures: The Battle over Democracy in Hong Kong, 19 N.C. J. Int'l L. & Com. Reg. 175 (1993). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol19/iss1/6 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Envisioning Futures: The aB ttle veo r Democracy in Hong Kong Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This comments is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol19/iss1/6 Envisioning Futures: The Battle Over Democracy in Hong Kong I. Introduction Hong Kong has entered its last years under British administration, and the dramatic final act is being played out.1 When Hong Kong reverts to Chinese rule, it will do so under the protection of the Basic Law,2 a mini-constitution created pursuant to a Joint Declaration 3 be- tween the United Kingdom and the People's Republic of China (PRC) that delineates the principles under which Hong Kong will be gov- erned. The former and future rulers of the city diverge widely in their political, economic, and social systems, and despite the elaborate detail of the relevant treaties providing for the transfer,4 there have been disagreements during the period of transition. -

Airline Contact Details

Airline contact details Airline Region Country Link Aegean Airlines Europe Greece Link Aer Lingus Europe Ireland Link Aeroflot Europe Russia Link Aerolineas Argen:nas La:n America Argen:na Link Aeromexico North America Mexico Link Air Busan Asia South Korea Link Air Canada North America Canada Link Air Caraibes La:n America Guadeloupe Link Air China Asia China Link Air Europa Europe Spain Link Air France Europe France Link Air India Asia India Link Air New Zealand Southwest Pacific New Zealand Link Air Serbia Europe Serbia Link AirAsia Asia Malaysia Link Alaska Air Group North America U.S. Link Alitalia Europe Italy Link Allegiant Air North America U.S. Link American Airlines North America U.S. Link All Nippon Airways (ANA) Asia Japan Link Asiana Airlines Asia South Korea Link Austrian Airlines Europe Austria Link Avianca La:n America Colombia Link Azul Airlines La:n America Brazil Link Bangkok Airways Asia Thailand Link Bri:sh Airways Europe U.K. Link Brussels Airlines Europe Belgium Link Bulgaria Air Europe Bulgaria Link Caribbean Airlines La:n America Trinidad & Tobago Link Cathay Pacific Asia Hong Kong Link Cebu Pacific Asia Philippines Link China Airlines Asia Taiwan Link China Eastern Asia China Link China Southern Asia China Link Copa Airlines La:n America Panama Link Croa:a Airlines Europe Croata Link Czech Airlines Europe Czech Republic Link Delta Air Lines North America U.S. Link easyJet Europe U.K. Link Egyptair Africa Egypt Link El Al Middle East Israel Link Emirates Middle East U.A.E. Link Ethiopian Airlines Africa Ethiopia Link Ehad Airways Middle East U.A.E. -

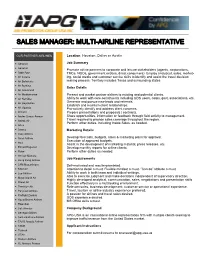

Sales Manager: Multi-Airline Representative

SALES MANAGER: MULTI-AIRLINE REPRESENTATIVE OUR PARTNER AIRLINES Location: Houston, Dallas or Austin Aerocon Job Summary Aeromar Promote airline partners to corporate and leisure stakeholders (agents, corporations, Aigle Azur TMCs, NGOs, government entities, direct consumers). Employ analytical, sales, market- Air Astana ing, social media and customer service skills to identify and assist the travel decision Air Botswana making process. Territory includes Texas and surrounding states. Air Burkina Sales Details Air Greenland Air Mediterranee Present and market partner airlines to existing and potential clients. Air Namibia Ability to work with core constituents including GDS users, corps, govt, associations, etc. Generate and pursue new leads and referrals. Air Seychelles Establish and maintain client relationships. Air Uganda Pro-actively identify and address client concerns. Aircalin Prepare presentations and proposals | contracts. Andes Lineas Aereas Share opportunities, information or feedback through field activity to management. Antrak Air Travel required to provide sales coverage throughout the region. Perform other duties, including Inside Sales, as needed. Arkia Aserca Marketing Details Asky Airlines Avior Airlines Develop forecasts, budgets, sales & marketing plans for approval. Execution of approved budgets. Azul Assist in the development of marketing material, press releases, etc. Etihad Regional Develop monthly reports for airline clients. Flybe Perform other duties as needed. Heli Air Monaco Job Requirements Hong Kong Airlines LAM Mozambique Self-motivated and results-orientated. KAM Air Attention to detail a must. Flexible mindset a must. “Can do” attitude a must. Lao Airlines Ability to work in both team and individual settings. Able to exercise judgment and make decisions independent of supervisory direction. Maya Island Air Highly developed analytical, communication, sales, negotiations and presentation skills Oman Air Function effectively in a multitasking environment. -

List of Approved Training Organisations

Date: 11 August 2021 Approved Training Organisations (Type Rating) Under Article 20(11) to the Air Navigation (Hong Kong) Order 1995 Name, Address, and Website (if available) of the Approved Organisations Approval Reference No. Name: Cathay Pacific Airways Limited AL/020/2020 Address: Cathay Pacific City, 8 Scenic Road, Hong Kong International Airport, Lantau, Hong Kong Website: https://www.cathaypacific.com/cx/en_HK.html Name: Hong Kong Airlines Limited AL/053/2020 Address: South Wing 8th Floor, HKA Training Academy Tower, 28 Kwo Lo Wan Road, Hong Kong International Airport, Lantau, Hong Kong. Website: https://www.hongkongairlines.com/en_HK/homepage Name: Heliservices (Hong Kong) Limited AL/028/2021 Address: Suite 1801, 18th Floor, Chinachem Johnston Plaza, 178-186 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong Website: http://heliservices.com.hk/en/ Name: CAE Centre Hong Kong Limited AL/014/2021 Address: 5/F, South Wing, HKA Training Academy Tower, 28 Kwo Lo Wan Road, Hong Kong International Airport, Lantau, Hong Kong Website: https://www.cae.com/civil-aviation/locations/cae-hong- kong-at-hka-training-academy Page 1 of 2 Date: 11 August 2021 Name: Emirates - CAE Flight Training (ECFT) AL/055/2020 Address: Emirates Aviation College Building B, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, P.O. Box 111066 Website: https://www.cae.com/civil-aviation/locations/cae-dubai-al- garhoud-emirates-cae-flight-training/ Name: Government Flying Service AL/029/2021 Address: 18 South Perimeter Road, Hong Kong International Airport, Lantau, Hong Kong Website: https://www.gfs.gov.hk/eng/home.htm Note: The information listed in the above table is current at the time of issuance. -

Tropical Cyclones in 1991

ROYAL OBSERVATORY HONG KONG TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 1991 CROWN COPYRIGHT RESERVED Published March 1993 Prepared by Royal Observatory 134A Nathan Road Kowloon Hong Kong Permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be obtained through the Royal Observatory This publication is prepared and disseminated in the interest of promoting the exchange of information. The Government of Hong Kong (including its servants and agents) makes no warranty, statement or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained herein, and in so far as permitted by law, shall not have any legal liability or responsibility (including liability for negligence) for any loss, damage or injury (including death) which may result whether directly or indirectly, from the supply or use of such information. This publication is available from: Government Publications Centre General Post Office Building Ground Floor Connaught Place Hong Kong 551.515.2:551.506.1 (512.317) 3 CONTENTS Page FRONTISPIECE: Tracks of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific and the South China Sea in 1991 FIGURES 4 TABLES 5 HONG KONG'S TROPICAL CYCLONE WARNING SIGNALS 6 1. INTRODUCTION 7 2. TROPICAL CYCLONE OVERVIEW FOR 1991 11 3. REPORTS ON TROPICAL CYCLONES AFFECTING HONG KONG IN 1991 19 (a) Typhoon Zeke (9106): 9-14 July 20 (b) Typhoon Amy (9107): 16-19 July 24 (c) Severe Tropical Storm Brendan (9108): 20-24 July 28 (d) Typhoon Fred (9111): 13-l8 August 34 (e) Severe Tropical Storm Joel (9116): 3-7 September 40 (f) Typhoon Nat (9120): 16 September-2 October 44 4. -

Approved DH Carrier List

Approved DH Carrier List Airline Country Class Aer Lingus Ireland Class 1 (Good) airberlin Germany Class 1 (Good) British Airways United Kingdom Class 1 (Good) Brussels Airlines Belgium Class 1 (Good) Cyprus Airways Cyprus Class 1 (Good) Delta Air Lines United States Class 1 (Good) Dragonair China Class 1 (Good) Etihad Airways United Arab Emirates Class 1 (Good) Eurowings (Lufthansa Regional) Germany Class 1 (Good) EVA Air Taiwan Class 1 (Good) Finnair Finland Class 1 (Good) Frontier Airlines United States Class 1 (Good) Germanwings Germany Class 1 (Good) Hawaiian Airlines United States Class 1 (Good) Horizon Air (Alaska Horizon) United States Class 1 (Good) Iberia Spain Class 1 (Good) Icelandair Iceland Class 1 (Good) Japan Airlines (JAL) Japan Class 1 (Good) JetBlue Airways United States Class 1 (Good) Jetstar Asia Singapore Class 1 (Good) Lufthansa Germany Class 1 (Good) SAS (Scandinavian Airlines System) Sweden Class 1 (Good) SilkAir - MI Singapore Class 1 (Good) Singapore Airlines Singapore Class 1 (Good) SkyWest Airlines United States Class 1 (Good) Southwest Airlines (AirTran Airways) United States Class 1 (Good) Swiss Switzerland Class 1 (Good) TAP Portugal Portugal Class 1 (Good) United Airlines United States Class 1 (Good) Virgin America United States Class 1 (Good) Virgin Atlantic Airways United Kingdom Class 1 (Good) Virgin Australia Australia Class 1 (Good) Air Canada Canada Class 2 (Adequate) Air China China Class 2 (Adequate) Air France France Class 2 (Adequate) Air Jamaica Jamaica Class 2 (Adequate) Air New Zealand New -

Family Friendly Airline List

Family Friendly airline list Over 50 airlines officially approve the BedBox™! Below is a list of family friendly airlines, where you may use the BedBox™ sleeping function. The BedBox™ has been thoroughly assessed and approved by many major airlines. Airlines such as Singapore Airlines and Cathay Pacific are also selling the BedBox™. Many airlines do not have a specific policy towards personal comforts devices like the BedBox™, but still allow its use. Therefore, we continuously aim to keep this list up to date, based on user feedback, our knowledge, and our communication with the relevant airline. Aeromexico Japan Airlines - JAL Air Arabia Maroc Jet Airways Air Asia Jet Time Air Asia X Air Austral JetBlue Air Baltic Kenya Airways Air Belgium KLM Air Calin Kuwait Airways Air Caraibes La Compagnie Air China LATAM Air Europa LEVEL Air India Lion Airlines Air India Express LOT Polish Airlines Air Italy Luxair Air Malta Malaysia Airlines Air Mauritius Malindo Air Serbia Middle East Airlines Air Tahiti Nui Nok Air Air Transat Nordwind Airlines Air Vanuatu Norwegian Alaska Airlines Oman Air Alitalia OpenSkies Allegiant Pakistan International Airlines Alliance Airlines Peach Aviation American Airlines LOT Polish Airlines ANA - Air Japan Porter AtlasGlobal Regional Express Avianca Royal Air Maroc Azerbaijan Hava Yollary Royal Brunei AZUL Brazilian Airlines Royal Jordanian Bangkok Airways Ryanair Blue Air S7 Airlines Bmi regional SAS Brussels Airlines Saudia Cathay Dragon Scoot Cathay Pacific Silk Air CEBU Pacific Air Singapore Airlines China Airlines