Memory, Family, and Self

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volta, the Istituto Nazionale and Scientific Communication in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy*

Luigi Pepe Volta, the Istituto Nazionale and Scientific Communication in Early Nineteenth-Century Italy* In a famous paper published in Isis in 1969, Maurice Crosland posed the question as to which was the first international scientific congress. Historians of science commonly established it as the Karlsruhe Congress of 1860 whose subject was chemical notation and atomic weights. Crosland suggested that the first international scientific congress could be considered the meeting convened in Paris on January 20, 1798 for the definition of the metric system.1 In September 1798 there arrived in Paris Bugge from Denmark, van Swinden and Aeneae from Germany, Trallès from Switzerland, Ciscar and Pedrayes from Spain, Balbo, Mascheroni, Multedo, Franchini and Fabbroni from Italy. These scientists joined the several scientists already living in Paris and engaged in the definition of the metric system: Coulomb, Mechain, Delambre, Laplace, Legendre, Lagrange, etc. English and American scientists, however, did not take part in the meeting. The same question could be asked regarding the first national congress in England, in Germany, in Switzerland, in Italy, etc. As far as Italy is concerned, many historians of science would date the first meeting of Italian scientists (Prima Riunione degli Scienziati Italiani) as the one held in Pisa in 1839. This meeting was organised by Carlo Luciano Bonaparte, Napoleon’s nephew, with the co-operation of the mathematician Gaetano Giorgini under the sanction of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Leopold II (Leopold was a member of the Royal Society).2 Participation in the meetings of the Italian scientists, held annually from 1839 for nine years, was high: * This research was made possible by support from C.N.R. -

Education and Politics in Piedmont, 1796-1814 Author(S): Dorinda Outram Source: the Historical Journal, Vol

Education and Politics in Piedmont, 1796-1814 Author(s): Dorinda Outram Source: The Historical Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3 (Sep., 1976), pp. 611-633 Published by: Cambridge University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2638223 . Accessed: 03/06/2013 15:52 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Historical Journal. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.167.140.2 on Mon, 3 Jun 2013 15:52:02 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The Historical Journal, 19, 3 (I976), pp. 6I I-633 Printed in Great Britain EDUCATION AND POLITICS IN PIEDMONT, 1796-18 14 DORINDA OUTRAM University of Reading In I820 many of the leading figures in the governments of the Italian states were men who had already been prominent before 1796, and had collaborated with the French during the period of the Empire. Vittorio Fossombroni and Neri Corsini in Tuscany' and Prospero Balbo in Piedmont2 are the outstanding examples in the years immediately follow- ing the Vienna settlement. The political survival of these men into a Europe dominated by violent reaction against the events of the preceding twenty years poses interesting questions. -

Year 7 Issue 7 October 2016 a Monthly National

A Monthly National Review October 2016 “Let us all work for the Greatness of India.” – The Mother Year 7 Issue 7 The Resurgent India 1 October 2016 The Resurgent India English monthly published and printed by Smt. Suman Sharma on behalf of The Resurgent India Trust Published at C/o J.N. Socketed Cement Pipes Pvt. Ltd., Village Bhamraula Post Bagwara, Kichha Road, Rudrapur (U.S Nagar) email: [email protected], [email protected], URL : www.resurgentindia.org Printed at : Priyanka Printing Press, Hotel Krish Building, Janta Inter College Road, Udham Nagar, Rudrapur, Uttarakhand Editor : Ms. Garima Sharma, B-45, Batra Colony, Village Bharatpur, P.O. Kaushal Ganj, Bilaspur Distt. Rampur (U.P) The Resurgent India 2 October 2016 THE RESURGENT INDIA A Monthly National Review October 2016 SUCCESSFUL FUTURE (Full of Promise and Joyful Surprises) Botanical name: Gaillardia Pulchella Common name: Indian blanket, Blanket flower, Fire-wheels Year 7 Issue 7 The Resurgent India 3 October 2016 CONTENTS Surgical Strikes Reveal the Reality of Our Politicians ...................................................... 6 Straight from the Horse’s Mouth ...........................................7 An End to Politics ................................................................... 8 The Overwhelming Evidence in Favour of the Traditional Indian Date for the Beginning of the Kaliyuga and the Mahabharata War .........10 1. The Aihole Inscription of King Pulakesin II and Its Implications for the Modern Historical Dating of the Mahabharata War ........ 10 2. The Superfluity of the Arguments Against the Historicity of the Kaliyuga Era and Their Repudiation ..................... 13 3. The Brihatsamhita of Varahamihira .................................. 18 4. Alberuni’s Indica and the Rajatarangini of Kalhana .......... 23 5. The Records in the Annual Indian Calendars – The Panchangas .... -

Äs T Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 No. 2 (May 1978)

.** äs t Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 no. 2 (May 1978), ISLAMIC NUMISMATICS Sections l and 2 by Michael L. Bates The American Numismatic Society Every Student of pre-raodern Islamic political, social, economic, or cultural history is aware in a general way of the importance of nuraisraatic evidence, but it has to be admitted thst for the roost part this awareness is evidenced raore in lip ser-vice than in practice. Too many historians consider numismatics an arcane and complex study best left to specialists. All too often, histori- ans, if they take coin evidence into account at all, suspend their normal critical judgement to accept without cjuestion the readings and interpretations of the numismatist. Or. the other hand, numismatists, in the past especially but to a large extent still today, are often amateurs, self-taught through practice with little or no formal.historical and linguistic training. This is true even öf museum Professionals in Charge of Islamic collections, ho matter what their previous training: The need tc deal with the coinage of fourteen centuries, from Morocco to the Fr.ilippines, means that the curator spends most of his time workir.g in areas in which he is, by scholarly Standards, a layman. The best qual- ified Student of any coin series is the specialist with an ex- pert knowledge of the historical context from which the coinage coraes. Ideally, any serious research on a particular region and era should rest upon äs intensive a study of the nvunismatic evi- dence äs of the literary sources. In practice, of course, it is not so easy, but it is easier than many scholars believe, and cer- tainly much «asier than for a numismatist to become =. -

THE EVERLASTING GOSPEL by Dr. Wesley A. Swift 5-7-61 We Are

THE EVERLASTING GOSPEL by Dr. Wesley A. Swift 5-7-61 We are turning this afternoon to re-evaluate what is meant by the Everlasting Gospel. If you will turn to the book of Revelation, you will find that this is the only time this has been used as such and this is in the 6th verse of the 14th chapter of the book of Revelation, when John said, ‘I saw the Angel flying in the midst of the heavens having the Everlasting Gospel to preach to them that dwell on earth, to every nation and kindred and tongue and people.’ Now, we know what the Gospel means. We know that it is ‘glad tidings of great joy.’ We know that the word ‘gospel’ is not a message of fear, but a message of Light and Truth. We know that the Everlasting Gospel is a Gospel that is a continuous Gospel and it runs from generation to generation. We know that it is a gospel of Divine intent and a Divine purpose. And we have it continued into another passage which is also Everlasting. I would have you go back into the book of Genesis. And in the 17th chapter of Genesis, we read these words:--’As God speaks to Abraham, He says, ‘I will call you no more Abram, but your name shall be Abraham ‘father of many nations have I made thee.’ I shall make nations of thee and kings shall come out of thee. And I will establish MY Covenant between thee and ME, and thy seed after thee in their generations, for an Everlasting Covenant, that I will be a God unto thee and to thy seed after thee.’ There are no conditions on this. -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family. -

2013 Bologna Artelibro Book Fair List

Artelibro Bologna 19 - 22 September 2013 Bernard Quaritch Ltd 1.AGRATI, Giuseppe. Delle sedizioni di Francia. Cenni storici di G. Agrati onde illustrare un discorso di Torquato Tasso; a cui se ne aggiugne un altro del maresciallo di Biron: si questo che quello tolti da manoscritti inediti. Brescia, Nicolò Bettoni, 1819. Large 16mo, pp. viii, 160; occasional very light spotting, some foxing on edges, but a crisp, tight, clean copy; nineteenth-century ownership inscription of Dr. Antonio Greppi, recording the book as a gift from Domenico Agrati, the author’s brother; contemporary boards, ink titling on spine. € 310 First and only edition, rare. Styled as the ‘transcription’ of unpublished manuscripts by Tasso and Biron on the French unrest from Calvin to Nantes, this publication was in fact intended to support the reaction of European aristocracy against the outcome and repercussions of the French Revolution. Hume’s and Rousseau’s visions of popular fury depict the violence of the French ‘populace’. Throughout history, Agrati argues, the French have fomented factions, incited rebellion and regularly spoiled the constructive efforts of well-meaning monarchs. In line with the spirit that had just animated the Congress of Vienna, Agrati maintains that only a ‘firm and absolute’ (p. 153) ruler can avert the lethal threat of anarchy. Rare outside Italy: one copy at BL, one listed in OCLC (Alberta). ALBERTI’S POLITICAL THOUGHT 2.ALBERTI, Leon Battista. Momus [or De principe]. Rome, Jacopo Mazochi, 1520. 4to., 104 leaves, including a leaf of errata at end; printed in roman letter, several large white-on-black initial letters; some light spotting but a very good large copy in marbled paper boards with paper spine label. -

The Queen, the Populists and the Others

VU Research Portal The Queen, the Populists and the Others. New Dutch Politics explained to foreigners. Sap, J.W. 2010 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Sap, J. W. (2010). The Queen, the Populists and the Others. New Dutch Politics explained to foreigners. VU University Press. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 jan willem sap sap willem jan Outsiders look with surprise at the climate The Queen, change in the Netherlands. As well as the Dutch themselves. Their country seemed to be a multi-cultural paradise. But today popu- lists are dominating politics and media. Much to the chagrin of the old political elite, includ- ing the progressive Head of State, Queen Beatrix. -

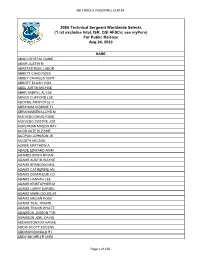

20E6 List Format.Xlsx

AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER 20E6 Technical Sergeant Worldwide Selects (*List excludes Intel, ISR, OSI AFSCs; see myPers) For Public Release Aug 24, 2020 NAME ABAD CRYSTAL DANIE ABAIR JUSTIN M ABASTAS RUEL LABOR ABBETT CHAD ROSS ABBEY CHARLES CURT ABBOTT ELIJAH VON ABEL JUSTIN MICHAE ABER SHERYL ALYSE ABNER CLIFFORD LEE ABOYME ARISTOTLE H ABRAHAM JASMINE TI ABRAHAMSEN LLOYD M ACEVEDO DAVID ROBE ACEVEDO SOSTRE JOS ACKERMAN MASON RAY ACOB KATE BLESSIE ACOPAN JOHNSON JR ACOSTA NELSON ACREE MATTHEW A ADADE EDWARD ANIM ADAMES ERICA BRIAN ADAMS AUSTIN WAYNE ADAMS BRANDON NEIL ADAMS CATHERINE AN ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO ADAMS HANNAH LEE ADAMS KRISTOPHER M ADAMS LARRY DARNEL ADAMS MARK DOUGLAS ADAMS MEGAN ROSE ADAMS TEAL TRAVIS ADAMS TRAVIS WYATT ADAMSON JASSON TYR ADAMSON JOEL DAVID ADDINGTON NATHANAE ADDIS SCOTT EUGENE ADDISON DONALD R I ADDY MICHELLE CHRI Page 1 of 166 AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER ADKINS AUSTIN JAME ADKINS DUSTIN ZANE ADKINS MICHAEL ARR ADKINS NOBLE BEREA ADKINS SETH VON AGBAY ALLENJOHN CR AGGEN ELIAS CHARLE AGLUBAT JASON FERN AGOUN JAMAL AGRI HUSNI MUBARAK AGUILAR ANDRE J AGUILAR ANN GRACE AGUILAR FITTS ANTH AGUILAR MARVIN AGUILAR SABRINA IS AGUILERA ANNA KARE AGUILERA TORRES JE AGUINALDO JAYCOB K AGUIRRE JOSE LUIS AHLERS RANDY JOHN AHMAD JESSE D AHRENS COREY AUSTI AHRENT BRITTANY JO AIKENS GABRIEL MAR AITCHISON DANIELLE AKALANZE KELISSA A AKINS REX TREY AKINWALE FOLARIN AL DALAWI MOHAMED ALAPAG ZHARINA A ALARCON MYLENE TEO ALBANO THOMAS L ALBERT COTY DAVID ALBIA ELIGIUSAUREL ALBIAR ANDREI OMAR ALBINO CHARNELLE S ALBRITTON MICHAEL -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. In their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Lingjie Ji Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Asian Studies (Chinese) School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures The University of Edinburgh 2017 Declaration I hereby affirm that all work in this thesis is my own work and has been composed by me solely. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Name: Lingjie Ji Date: 23/11/2017 Abstract of Thesis See the Postgraduate Assessment Regulations for Research Degrees: www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/academic-services/policies- regulations/regulations/assessment Name of student: Lingjie Ji UUN S1356381 University email: [email protected] Degree sought: Doctorate No. of words in the 95083 main text of thesis: Title of thesis: In Their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Insert the abstract text here - the space will expand as you type. -

Understanding Human History

hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page i UNDERSTANDING HUMAN HISTORY hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page ii Other books by Michael H. Hart The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History A View from the Year 3000 hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page iii UNDERSTANDING HUMAN HISTORY An analysis including the effects of geography and differential evolution by MICHAEL H. HART Washington Summit Publishers Augusta, GA A National Policy Institute Book 2007 hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page iv © 2007 Michael H. Hart All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other elec- tronic or mechanical methods, or by any information storage and retrieval system, with- out prior written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations embedded in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. Washington Summit Publishers P.O. Box 3514 Augusta, GA 30914 Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hart, Michael H. Understanding Human History : an analysis including the effects of geography and differential evolution / by Michael H. Hart. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and an index. ISBN-13: 978-1-59368-027-5 (hardcover) ISBN-10: 1-59368-027-9 (hardcover) ISBN-13: 978-1-59368-026-8 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-59368-026-0 (pbk.) 1. Civilization--History. 2. -

Cirm Trento – 2014 – Iolanda Nagliati

The journals of mathematics at the University of Pisa and European influences Iolanda Nagliati Mathematics and International Relationships in Print and Correspondence CIRM (Trento) Pisa and its University: . peculiar situation . long history of journals 1771 – present The journals Giornale de' letterati 1 (1771) - 102 (1796) Nuovo giornale de’ letterati 1 (1802) - 8 (1803) n.s. 1 (1804) - 4 (1806) Giornale pisano de' letterati 5 (1806) - 11 (1809) Giornale scientifico e letterario dell'Accademia italiana di scienze, lettere e arti 1 (1810) - 2 (1810) Nuovo giornale de' letterati 1 (1822) - 39 (1839) (Pisa 1839: First Congress of Italian Scientists) Antologia (1821-1832) Giornale Toscano di scienze mediche, fisiche e naturali 1840-43 Giornale di scienze morali, sociali, storiche e filologiche 1841 Miscellanee medico – chirurgiche farmaceutiche 1843, 2 vols Miscellanee di chimica, fisica, e storia naturale 1843 Il Cimento 1844-47, 5 vols (1855 Nuovo Cimento) Annali delle Università Toscane 1(1846) – 34 (1915) n.s. 1 (1916) – 9 (1924) Annali della Scuola Normale 1871 – 1930 (I s.) 1932 – 1950, 1951 – 1973, 1974 – 1997 1997 – Giornale de’ letterati (1771-1796) • Organ of the board of professors (strengths and weaknesses) • title inspired by the Journal des savants • Angelo Fabroni superintendent and director of the journal • One of the most influential journal in Italy in late XVII century • Rediscovery of Galileo: claim of scientific merits of Tuscany • 1796 Fabroni yields to Giovanni Rosini its printing activities Angelo Fabroni (1732 – 1803) “privilegio” to print in his home → very rapid circulation by sending to subscribers Giornale sold in Pisa, Florence, Rome, Bologna, Milan, Siena, Naples Explicit and continuos attention to foreign authors Abroad (Fabroni’s correspondence – journey in 1773): • d’Alembert • Bernoulli • Condorcet, • J.D.Cassini • count of Hertzberg • abbot Bartélhemy Importance of the Vitae First history of the university 1770 proposal (T.