Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comune Di San Venanzo |

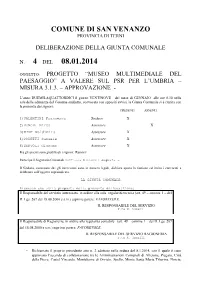

COMUNE DI SAN VENANZO PROVINCIA DI TERNI DELIBERAZIONE DELLA GIUNTA COMUNALE N. 4 DEL 08.01.2014 OGGETTO: PROGETTO “MUSEO MULTIMEDIALE DEL PAESAGGIO” A VALERE SUL PSR PER L’UMBRIA – MISURA 3.1.3. – APPROVAZIONE - L’anno DUEMILAQUATTORDICI il giorno VENTINOVE del mese di GENNAIO alle ore 8.30 nella sala delle adunanze del Comune suddetto, convocata con appositi avvisi, la Giunta Comunale si è riunita con la presenza dei signori: PRESENTI ASSENTI 1) VALENTINI Francesca Sindaco X 2) RUMORI Mirco Assessore X 3)BINI Waldimiro Assessore X 4) CODETTI Samuele Assessore X 5) SERVOLI Giacomo Assessore X Fra gli assenti sono giustificati i signori: Rumori/ Partecipa il Segretario Comunale Dott.ssa MILLUCCI Augusta – Il Sindaco, constatato che gli intervenuti sono in numero legale, dichiara aperta la riunione ed invita i convocati a deliberare sull’oggetto sopraindicato. LA GIUNTA COMUNALE Premesso che sulla proposta della presente deliberazione: Il Responsabile del servizio interessato, in ordine alla sola regolarità tecnica (art. 49 – comma 1 – del D. Lgs. 267 del 18.08.2000 e s.m.) esprime parere: FAVOREVOLE IL RESPONSABILE DEL SERVIZIO F.to M. Rumori Il Responsabile di Ragioneria, in ordine alla regolarità contabile (art. 49 – comma 1 – del D. Lgs. 267 del 18.08.2000 e s.m.) esprime parere: FAVOREVOLE IL RESPONSABILE DEL SERVIZIO RAGIONERIA F.to R. Tonelli - Richiamato il proprio precedente atto n. 2 adottato nella seduta del 8.1.2014, con il quale è stato approvato l’accordo di collaborazione tra le Amministrazioni Comunali di Allerona, Piegaro, -

Umbria from the Iron Age to the Augustan Era

UMBRIA FROM THE IRON AGE TO THE AUGUSTAN ERA PhD Guy Jolyon Bradley University College London BieC ILONOIK.] ProQuest Number: 10055445 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10055445 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract This thesis compares Umbria before and after the Roman conquest in order to assess the impact of the imposition of Roman control over this area of central Italy. There are four sections specifically on Umbria and two more general chapters of introduction and conclusion. The introductory chapter examines the most important issues for the history of the Italian regions in this period and the extent to which they are relevant to Umbria, given the type of evidence that survives. The chapter focuses on the concept of state formation, and the information about it provided by evidence for urbanisation, coinage, and the creation of treaties. The second chapter looks at the archaeological and other available evidence for the history of Umbria before the Roman conquest, and maps the beginnings of the formation of the state through the growth in social complexity, urbanisation and the emergence of cult places. -

Profile of a Plant: the Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE By

Profile of a Plant: The Olive in Early Medieval Italy, 400-900 CE by Benjamin Jon Graham A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paolo Squatriti, Chair Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes Professor Richard P. Tucker Professor Raymond H. Van Dam © Benjamin J. Graham, 2014 Acknowledgements Planting an olive tree is an act of faith. A cultivator must patiently protect, water, and till the soil around the plant for fifteen years before it begins to bear fruit. Though this dissertation is not nearly as useful or palatable as the olive’s pressed fruits, its slow growth to completion resembles the tree in as much as it was the patient and diligent kindness of my friends, mentors, and family that enabled me to finish the project. Mercifully it took fewer than fifteen years. My deepest thanks go to Paolo Squatriti, who provoked and inspired me to write an unconventional dissertation. I am unable to articulate the ways he has influenced my scholarship, teaching, and life. Ray Van Dam’s clarity of thought helped to shape and rein in my run-away ideas. Diane Hughes unfailingly saw the big picture—how the story of the olive connected to different strands of history. These three people in particular made graduate school a humane and deeply edifying experience. Joining them for the dissertation defense was Richard Tucker, whose capacious understanding of the history of the environment improved this work immensely. In addition to these, I would like to thank David Akin, Hussein Fancy, Tom Green, Alison Cornish, Kathleen King, Lorna Alstetter, Diana Denney, Terre Fisher, Liz Kamali, Jon Farr, Yanay Israeli, and Noah Blan, all at the University of Michigan, for their benevolence. -

Arm Und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in – Zur Ressourcenverteilung Arm Und Reich 2016 14/II

VORGESCHICHTE HALLE LANDESMUSEUMS FÜR DES TAGUNGEN in prähistorischen Gesellschaften in prähistorischen – Zur Ressourcenverteilung Arm und Reich Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Herausgeber Harald Meller, Hans Peter Hahn, Reinhard Jung und Roberto Risch 14/II 14/II 2016 TAGUNGEN DES LANDESMUSEUMS FÜR VORGESCHICHTE HALLE Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle Band 14/II | 2016 Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) 8th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany October 22–24, 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle Band 14/II | 2016 Arm und Reich – Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften Rich and Poor – Competing for resources in prehistoric societies 8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2o15 in Halle (Saale) 8th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany October 22–24, 2o15 in Halle (Saale) Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt landesmuseum für vorgeschichte herausgegeben von Harald Meller, Hans Peter Hahn, Reinhard Jung und Roberto Risch Halle (Saale) 2o16 Die Beiträge dieses Bandes wurden einem Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. Die Gutachtertätigkeit übernahmen folgende Fachkollegen: Prof. Dr. Eszter Bánffy, Prof. Dr. Jan Bemmann, PD Dr. Felix Biermann, Prof. Dr. Christoph Brumann, Prof. Dr. Robert Chap- man, Dr. Jens-Arne Dickmann, Dr. Michal Ernée, Prof. Dr. Andreas Furtwängler, Prof. Dr. Hans Peter Hahn, Prof. Dr. Svend Hansen, Prof. Dr. Barbara Horejs, PD Dr. Reinhard Jung, Dr. -

Passion for Cycling Tourism

TUSCANY if not HERE, where? PASSION FOR CYCLING TOURISM Tuscany offers you • Unique landscapes and climate • A journey into history and art: from Etruscans to Renaissance down to the present day • An extensive network of cycle paths, unpaved and paved roads with hardly any traffic • Unforgettable cuisine, superb wines and much more ... if not HERE, where? Tuscany is the ideal place for a relaxing cycling holiday: the routes are endless, from the paved roads of Chianti to trails through the forests of the Apennines and the Apuan Alps, from the coast to the historic routes and the eco-paths in nature photo: Enrico Borgogni reserves and through the Val d’Orcia. This guide has been designed to be an excellent travel companion as you ride from one valley, bike trail or cultural site to another, sometimes using the train, all according to the experiences reported by other cyclists. But that’s not all: in the guide you will find tips on where to eat and suggestions for exploring the various areas without overlooking small gems or important sites, with the added benefit of taking advantage of special conditions reserved for the owners of this guide. Therefore, this book is suitable not only for families and those who like easy routes, but can also be helpful to those who want to plan multiple-day excursions with higher levels of difficulty or across uscanyT for longer tours The suggested itineraries are only a part of the rich cycling opportunities that make Tuscany one of the paradises for this kind of activity, and have been selected giving priority to low-traffic roads, white roads or paths always in close contact with nature, trying to reach and show some of our region’s most interesting destinations. -

It001e00020532 Bt 6,6 Vocabolo Case Sparse 0

CODICE POD TIPO FORNITURA EE POTENZA IMPEGNATA INDIRIZZO SITO FORNITURA COMUNE FORNITURA IT001E00020532 BT 6,6 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020533 BT 3 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020534 BT 6 VOCABOLO CASE SPARSE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020535 BT 11 VIA DEI GELSI 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020536 BT 6 VIA MADONNA DELLA NEVE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020537 BT 22 VIA ROMA 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020538 BT 22 VOCABOLO SELVE 0 - 05028 - PENNA IN TEVERINA (TR) [IT] PENNA IN TEVERINA IT001E00020539 BT 6 VIA COL DI LANA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020540 BT 6 VIALE EUROPA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020541 BT 16,5 VIALE EUROPA 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020542 BT 6 VIALE J.F. KENNEDY 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020543 BT 11 LOCALITA' PIAN DI CASTELLO 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020544 BT 6 LOCALITA' RADICE 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020545 BT 6 VIALE UMBERTO I 0 - 05010 - PORANO (TR) [IT] PORANO IT001E00020546 BT 1,65 LOCALITA' PIANO MONTE 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020547 BT 63 VIA PROV. ARR. POLINO 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020548 MT 53 VIA PROV. ARR. POLINO 0 - 05030 - POLINO (TR) [IT] POLINO IT001E00020552 BT 22 LOCALITA' FAVAZZANO -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Chiarimenti Interpretativi

Avviso a sostegno delle nuove iniziative imprenditoriali in attuazione della legge regionale 14 febbraio 2018, n. 1 Capo VI “Autoimpiego e creazione d’impresa” Chiarimenti interpretativi: FAQ 1. – Ci sono requisiti di età per la presentazione delle domande? Non ci sono requisiti di età per la presentazione delle domande. FAQ 2. – Occorre essere disoccupati per presentare la domanda? No, non occorre essere disoccupati per presentare la domanda. FAQ 3. Si può presentare domanda se non si è costituita l’impresa? No, per presentare domanda l’impresa deve essere già giuridicamente costituita. FAQ 4. Si può trasmettere la domanda via pec o via raccomandata? No, la domanda deve essere inviata unicamente attraverso la procedura telematica indicata nell’Avviso. FAQ 5. - Come si calcola il numero degli occupati? Il numero degli occupati deve essere inserito nella tabella di calcolo dell’Indice di Priorità in base alle risultanze dell’Attestazione Uniemens di denuncia contributiva rilasciata dall’INPS, relativa al mese precedente a quello di compilazione della domanda o la prima attestazione utile in caso di impresa di nuova costituzione. Ai fini del calcolo occorre inserire il solo numero dei dipendenti a tempo indeterminato, ivi compresi gli apprendisti. In caso di dipendenti part-time, ciascuna unità lavorativa concorrerà al calcolo dell’indice in proporzione alla tipologia di part- time (es. 50%, 30% ecc.) risultante dalla busta paga del mese precedente a quello di presentazione della domanda. FAQ 6. – Se un dipendente è anche socio o titolare dell’impresa, quali campi devono essere compilati? Se un dipendente dell’impresa è anche socio, dovrà essere valorizzato soltanto il campo NUMERO SOCI e non quello NUMERO DIPENDENTI. -

Informazione, Cartacei E on Line, Consentendo, Così

gianno 2016 oIvNFORe MA \ Verso una scuola più sicura \ Un anno di intensa attività \ 2016: Consuntivo e Prospettive \ Ma la minoranza...che fa? \ Stagioni...in biblioteca \ Solidarietà con le popolazioni colpite dal terremoto \ La Pro Loco di Giove \ AVIS \ E. Berti Marini \ Associazione Nazionale Combattenti e Reduci \ Il Corteo Storico di Giove \ Associazione culturale Il Leccio Comune di Giove Editoriale COMUNE DI GIOVE ORARIO AL PUBBLICO e RESPONSABILI Verso una scuola DEGLI UFFICI COMUNALI per il 2017 più sicura UFFICI GIORNI Cari Giovesi, ha fatto nel corso degli Morelli dell’Università di anche da noi, sono stati ef - siamo arrivati alla fine di un anni, sta facendo ora ed ha Roma. L’analisi conferma la fettuati due sopralluoghi LUN MAR MER GIO VEN anno che non si può dire intenzione di fare in futuro stabilità dell’edificio; nell’edificio, Il primo dal certo eccezionale, segnato per migliorare la sicurezza • 10 aprile 2009, a seguito sottoscritto, quale respon - SEGRETARIO COMUNALE da eventi drammatici nel della nostra scuola con del terremoto in Abruzzo sabile del settore tecnico 9.00 - 12.00 (Dott.ssa V. Fortino) mondo ed in Italia tra i quali l’obiettivo, comunque sem - (6,3 gradi scala Richter) i ambiente e patrimonio, ed quello che ci ha interessato pre presente, di perseguire sopralluoghi effettuati dai il secondo dai tecnici del AFFARI GENERALI, DEMOGRAFIA, più da vicino è stato (e con - tutte le possibilità per co - tecnici comunali non comando VV.F di Terni, STATO CIVILE, PROTOCOLLO, 9.00 - 12.00 09.00-12.00 9.00 - 12.00 09.00-12.00 9.00 - 12.00 tinua ad essere, purtroppo) struirne un’altra migliore. -

Ovid at Falerii

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2014 The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Farrell, Joseph. (2014). “The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at alerii.F ” In D. P. Nelis and Manuel Royo (Eds.), Lire la Ville: fragments d’une archéologie littéraire de Rome antique (pp. 215–236). Bordeaux: Éditions Ausonius. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Poet in an Artificial Landscape: Ovid at Falerii Abstract For Ovid, erotic elegy is a quintessentially urban genre. In the Amores, excursions outside the city are infrequent. Distance from the city generally equals distance from the beloved, and so from the life of the lover. This is peculiarly true of Amores, 3.13, a poem that seems to signal the end of Ovid’s career as a literary lover and to predict his future as a poet of rituals and antiquities. For a student of poetry, it is tempting to read the landscape of such a poem as purely symbolic; and I will begin by sketching such a reading. But, as we will see, testing this reading against what can be known about the actual landscape in which the poem is set forces a revision of the results. And this revision is twofold. In the first instance, taking into account certain specific eaturf es of the landscape makes possible the correction of the particular, somewhat limited interpretive hypothesis that a purely literary reading would most probably recommend, and this is valuable in itself. -

Scarichi in Pubblica Fognatura

Scarichi in pubblica fognatura SCARICHI IN PUBBLICA FOGNATURA DA ATTIVITÀ PRODUTTIVE AUTORIZZAZIONE UNICA AMBIENTALE Con il DPR n. 59 del 13 marzo 2013, è stata introdotta l'Autorizzazione Unica Ambientale (AUA), provvedimento che incorpora in un unico atto diverse autorizzazioni ambientali previste dalla normativa di settore. Tutte le categorie di piccole e medie imprese, come definite dal Dm 18 aprile 2005, nonché agli impianti non soggetti ad Autorizzazione Integrata Ambientale (AIA) e a Valutazione d'Impatto Ambientale (VIA), dovranno presentare domanda di autorizzazione unica ambientale nel caso in cui siano assoggettati, ai sensi della normativa vigente, al rilascio, alla formazione, al rinnovo o all'aggiornamento di almeno uno dei seguenti titoli abilitativi: a) autorizzazione agli scarichi di acque reflue (Capo II Titolo IV Sezione II Parte terza del D.Lgs. 152/2006); b) comunicazione preventiva per l'utilizzazione agronomica degli effluenti di allevamento, delle acque di vegetazione dei frantoi oleari e delle acque reflue provenienti dalle aziende ivi previste (art. 112 D.Lgs. 152/2006); c) autorizzazione alle emissioni in atmosfera (art. 369 D.Lgs. 152/2006); d) autorizzazione di carattere generale alle emissioni in atmosfera (art.272 D.Lgs. 152/2006): e) documentazione previsionale di impatto acustico (art. 8 L.447/1995); f) autorizzazione all'utilizzo dei fanghi derivanti dal processo di depurazione in agricoltura (art.9 D.Lgs. 99/1992); g) comunicazioni in materia di rifiuti (artt. 215 e 216 D.Lgs. 152/2006). La domanda di AUA va presentata allo Sportello unico per le attività produttive e l'edilizia del comune competente per territorio (SUAPE) che la trasmette alla Regione Umbria (autorità competente ai fini del rilascio, rinnovo e aggiornamento dell'Autorizzazione Unica Ambientale) e ai soggetti competenti in materia ambientale che intervengono nei singoli procedimenti sostituiti dalla stessa AUA. -

La Via Appia

LA VIA APPIA Storia Alla fine del IV secolo a.C. Roma era padrona di gran parte della Penisola e una delle grandi potenze del Mediterraneo, solo pochi gruppi etnici, a sud delle Alpi, restavano da soggiogare. L'Urbe stessa stava cambiando il suo volto tradizionale assumendo quello di una capitale, ricca di opere pubbliche erette dai suoi generali vittoriosi. Il Foro, il Campidoglio, erano luoghi dove si ostentava la potenza crescente della città. Solo la nazione Sannita sfidava ancora l'egemonia di Roma da sud; da Paestum all'Apulia la Lega Sannitica minacciava di prendere Capua, non lontana dai confini del Lazio. La Via Appia nacque in questo contesto, come una via militare che consentiva di accelerare le comunicazioni coi confini meridionali del territorio conquistato. La strada fu poi estesa man mano che altri territori cadevano sotto il dominio di Roma. Appio Claudio Cieco, il console, fu colui che rese celebre la funzione di censore per le grandi imprese di interesse pubblico da lui realizzate, ma il suo nome fu reso famoso dalla Via Appia che gli sopravvisse. Nel 1993 la Via Appia compie 2305 anni, Appio fece tracciare la strada all'epoca delle guerre contro i Sanniti, nel 312 a.C., da Roma a Capua, per una distanza di 124 miglia romane. Appio impiegò anche i suoi capitali personali laddove le tesorerie dello stato erano insufficienti. Al primo posto fra tutte le strade di Roma c'era la Via Appia, a suo tempo la più lunga, la più bella, la più imponente via che fosse mai stata tracciata in alcuna parte del mondo, al punto che i romani la chiamarono "Regina di tutte le vie".