Number 5 — November 1919

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year 7 Issue 7 October 2016 a Monthly National

A Monthly National Review October 2016 “Let us all work for the Greatness of India.” – The Mother Year 7 Issue 7 The Resurgent India 1 October 2016 The Resurgent India English monthly published and printed by Smt. Suman Sharma on behalf of The Resurgent India Trust Published at C/o J.N. Socketed Cement Pipes Pvt. Ltd., Village Bhamraula Post Bagwara, Kichha Road, Rudrapur (U.S Nagar) email: [email protected], [email protected], URL : www.resurgentindia.org Printed at : Priyanka Printing Press, Hotel Krish Building, Janta Inter College Road, Udham Nagar, Rudrapur, Uttarakhand Editor : Ms. Garima Sharma, B-45, Batra Colony, Village Bharatpur, P.O. Kaushal Ganj, Bilaspur Distt. Rampur (U.P) The Resurgent India 2 October 2016 THE RESURGENT INDIA A Monthly National Review October 2016 SUCCESSFUL FUTURE (Full of Promise and Joyful Surprises) Botanical name: Gaillardia Pulchella Common name: Indian blanket, Blanket flower, Fire-wheels Year 7 Issue 7 The Resurgent India 3 October 2016 CONTENTS Surgical Strikes Reveal the Reality of Our Politicians ...................................................... 6 Straight from the Horse’s Mouth ...........................................7 An End to Politics ................................................................... 8 The Overwhelming Evidence in Favour of the Traditional Indian Date for the Beginning of the Kaliyuga and the Mahabharata War .........10 1. The Aihole Inscription of King Pulakesin II and Its Implications for the Modern Historical Dating of the Mahabharata War ........ 10 2. The Superfluity of the Arguments Against the Historicity of the Kaliyuga Era and Their Repudiation ..................... 13 3. The Brihatsamhita of Varahamihira .................................. 18 4. Alberuni’s Indica and the Rajatarangini of Kalhana .......... 23 5. The Records in the Annual Indian Calendars – The Panchangas .... -

Äs T Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 No. 2 (May 1978)

.** äs t Studies Association «Bulletin^ 12 no. 2 (May 1978), ISLAMIC NUMISMATICS Sections l and 2 by Michael L. Bates The American Numismatic Society Every Student of pre-raodern Islamic political, social, economic, or cultural history is aware in a general way of the importance of nuraisraatic evidence, but it has to be admitted thst for the roost part this awareness is evidenced raore in lip ser-vice than in practice. Too many historians consider numismatics an arcane and complex study best left to specialists. All too often, histori- ans, if they take coin evidence into account at all, suspend their normal critical judgement to accept without cjuestion the readings and interpretations of the numismatist. Or. the other hand, numismatists, in the past especially but to a large extent still today, are often amateurs, self-taught through practice with little or no formal.historical and linguistic training. This is true even öf museum Professionals in Charge of Islamic collections, ho matter what their previous training: The need tc deal with the coinage of fourteen centuries, from Morocco to the Fr.ilippines, means that the curator spends most of his time workir.g in areas in which he is, by scholarly Standards, a layman. The best qual- ified Student of any coin series is the specialist with an ex- pert knowledge of the historical context from which the coinage coraes. Ideally, any serious research on a particular region and era should rest upon äs intensive a study of the nvunismatic evi- dence äs of the literary sources. In practice, of course, it is not so easy, but it is easier than many scholars believe, and cer- tainly much «asier than for a numismatist to become =. -

THE EVERLASTING GOSPEL by Dr. Wesley A. Swift 5-7-61 We Are

THE EVERLASTING GOSPEL by Dr. Wesley A. Swift 5-7-61 We are turning this afternoon to re-evaluate what is meant by the Everlasting Gospel. If you will turn to the book of Revelation, you will find that this is the only time this has been used as such and this is in the 6th verse of the 14th chapter of the book of Revelation, when John said, ‘I saw the Angel flying in the midst of the heavens having the Everlasting Gospel to preach to them that dwell on earth, to every nation and kindred and tongue and people.’ Now, we know what the Gospel means. We know that it is ‘glad tidings of great joy.’ We know that the word ‘gospel’ is not a message of fear, but a message of Light and Truth. We know that the Everlasting Gospel is a Gospel that is a continuous Gospel and it runs from generation to generation. We know that it is a gospel of Divine intent and a Divine purpose. And we have it continued into another passage which is also Everlasting. I would have you go back into the book of Genesis. And in the 17th chapter of Genesis, we read these words:--’As God speaks to Abraham, He says, ‘I will call you no more Abram, but your name shall be Abraham ‘father of many nations have I made thee.’ I shall make nations of thee and kings shall come out of thee. And I will establish MY Covenant between thee and ME, and thy seed after thee in their generations, for an Everlasting Covenant, that I will be a God unto thee and to thy seed after thee.’ There are no conditions on this. -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family. -

The Queen, the Populists and the Others

VU Research Portal The Queen, the Populists and the Others. New Dutch Politics explained to foreigners. Sap, J.W. 2010 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Sap, J. W. (2010). The Queen, the Populists and the Others. New Dutch Politics explained to foreigners. VU University Press. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 jan willem sap sap willem jan Outsiders look with surprise at the climate The Queen, change in the Netherlands. As well as the Dutch themselves. Their country seemed to be a multi-cultural paradise. But today popu- lists are dominating politics and media. Much to the chagrin of the old political elite, includ- ing the progressive Head of State, Queen Beatrix. -

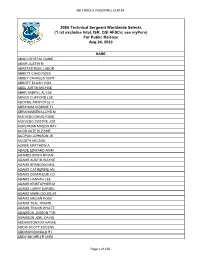

20E6 List Format.Xlsx

AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER 20E6 Technical Sergeant Worldwide Selects (*List excludes Intel, ISR, OSI AFSCs; see myPers) For Public Release Aug 24, 2020 NAME ABAD CRYSTAL DANIE ABAIR JUSTIN M ABASTAS RUEL LABOR ABBETT CHAD ROSS ABBEY CHARLES CURT ABBOTT ELIJAH VON ABEL JUSTIN MICHAE ABER SHERYL ALYSE ABNER CLIFFORD LEE ABOYME ARISTOTLE H ABRAHAM JASMINE TI ABRAHAMSEN LLOYD M ACEVEDO DAVID ROBE ACEVEDO SOSTRE JOS ACKERMAN MASON RAY ACOB KATE BLESSIE ACOPAN JOHNSON JR ACOSTA NELSON ACREE MATTHEW A ADADE EDWARD ANIM ADAMES ERICA BRIAN ADAMS AUSTIN WAYNE ADAMS BRANDON NEIL ADAMS CATHERINE AN ADAMS DOMINIQUE CO ADAMS HANNAH LEE ADAMS KRISTOPHER M ADAMS LARRY DARNEL ADAMS MARK DOUGLAS ADAMS MEGAN ROSE ADAMS TEAL TRAVIS ADAMS TRAVIS WYATT ADAMSON JASSON TYR ADAMSON JOEL DAVID ADDINGTON NATHANAE ADDIS SCOTT EUGENE ADDISON DONALD R I ADDY MICHELLE CHRI Page 1 of 166 AIR FORCE'S PERSONNEL CENTER ADKINS AUSTIN JAME ADKINS DUSTIN ZANE ADKINS MICHAEL ARR ADKINS NOBLE BEREA ADKINS SETH VON AGBAY ALLENJOHN CR AGGEN ELIAS CHARLE AGLUBAT JASON FERN AGOUN JAMAL AGRI HUSNI MUBARAK AGUILAR ANDRE J AGUILAR ANN GRACE AGUILAR FITTS ANTH AGUILAR MARVIN AGUILAR SABRINA IS AGUILERA ANNA KARE AGUILERA TORRES JE AGUINALDO JAYCOB K AGUIRRE JOSE LUIS AHLERS RANDY JOHN AHMAD JESSE D AHRENS COREY AUSTI AHRENT BRITTANY JO AIKENS GABRIEL MAR AITCHISON DANIELLE AKALANZE KELISSA A AKINS REX TREY AKINWALE FOLARIN AL DALAWI MOHAMED ALAPAG ZHARINA A ALARCON MYLENE TEO ALBANO THOMAS L ALBERT COTY DAVID ALBIA ELIGIUSAUREL ALBIAR ANDREI OMAR ALBINO CHARNELLE S ALBRITTON MICHAEL -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. In their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Lingjie Ji Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Asian Studies (Chinese) School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures The University of Edinburgh 2017 Declaration I hereby affirm that all work in this thesis is my own work and has been composed by me solely. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Name: Lingjie Ji Date: 23/11/2017 Abstract of Thesis See the Postgraduate Assessment Regulations for Research Degrees: www.ed.ac.uk/schools-departments/academic-services/policies- regulations/regulations/assessment Name of student: Lingjie Ji UUN S1356381 University email: [email protected] Degree sought: Doctorate No. of words in the 95083 main text of thesis: Title of thesis: In Their Own Words: British Sinologists’ Studies on Chinese Literature, 1807–1901 Insert the abstract text here - the space will expand as you type. -

Understanding Human History

hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page i UNDERSTANDING HUMAN HISTORY hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page ii Other books by Michael H. Hart The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History A View from the Year 3000 hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page iii UNDERSTANDING HUMAN HISTORY An analysis including the effects of geography and differential evolution by MICHAEL H. HART Washington Summit Publishers Augusta, GA A National Policy Institute Book 2007 hartbookfront2.qxp 3/1/2007 3:56 PM Page iv © 2007 Michael H. Hart All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or trans- mitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other elec- tronic or mechanical methods, or by any information storage and retrieval system, with- out prior written permission from the publisher, except for brief quotations embedded in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. Washington Summit Publishers P.O. Box 3514 Augusta, GA 30914 Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hart, Michael H. Understanding Human History : an analysis including the effects of geography and differential evolution / by Michael H. Hart. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and an index. ISBN-13: 978-1-59368-027-5 (hardcover) ISBN-10: 1-59368-027-9 (hardcover) ISBN-13: 978-1-59368-026-8 (pbk.) ISBN-10: 1-59368-026-0 (pbk.) 1. Civilization--History. 2. -

Dutch Royal Family

Dutch Royal Family A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 08 Nov 2013 22:31:29 UTC Contents Articles Dutch monarchs family tree 1 Chalon-Arlay 6 Philibert of Chalon 8 Claudia of Chalon 9 Henry III of Nassau-Breda 10 René of Chalon 14 House of Nassau 16 Johann V of Nassau-Vianden-Dietz 34 William I, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 35 Juliana of Stolberg 37 William the Silent 39 John VI, Count of Nassau-Dillenburg 53 Philip William, Prince of Orange 56 Maurice, Prince of Orange 58 Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange 63 Amalia of Solms-Braunfels 67 Ernest Casimir I, Count of Nassau-Dietz 70 William II, Prince of Orange 73 Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 77 Charles I of England 80 Countess Albertine Agnes of Nassau 107 William Frederick, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 110 William III of England 114 Mary II of England 133 Henry Casimir II, Prince of Nassau-Dietz 143 John William III, Duke of Saxe-Eisenach 145 John William Friso, Prince of Orange 147 Landgravine Marie Louise of Hesse-Kassel 150 Princess Amalia of Nassau-Dietz 155 Frederick, Hereditary Prince of Baden-Durlach 158 William IV, Prince of Orange 159 Anne, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange 163 George II of Great Britain 167 Princess Carolina of Orange-Nassau 184 Charles Christian, Prince of Nassau-Weilburg 186 William V, Prince of Orange 188 Wilhelmina of Prussia, Princess of Orange 192 Princess Louise of Orange-Nassau 195 William I of the Netherlands -

Ottoman Perception in the Byzantine Short Chronicles Bizans Kisa Kroniklerinde Osmanli Algisi

Ottoman Perception in The Byzantine Short Chronicles Bizans Kisa Kroniklerinde Osmanli Algisi Şahin KILIÇ* Abstract Anonymous chronicles, usually known as the Byzantine Short Chronicles, provide scholars of Ottoman history with rich and unique information about historical events having taken place until the 17th century. Majority of these chronicles, usually regarded as a part of “non-official historiography” due to their idiosyncratic features, were produced in rural monasteries of the Byzantine Empire. Even after the fall of Constantinople, these chronicles, which continued to emerge in the peripheries under the Ottoman domination or threat, provide an invaluable arena for examining Byzantine and post-Byzantine Orthodox Christian subjects’ visions of the Ottomans. The present study aims to explore the approaches of Byzantine authors toward Ottomans by focusing on the language and the vocabulary used for describing Ottomans. Key Words: Byzantine Short Chronicles, Byzantine Historiography, Ottoman Perception Öz Bizans Kısa Kronikleri olarak bilinen anonim kronikler, Osmanlı tarihçilerine 17.yy’a kadar uzanan olaylar hakkında zengin ve eşsiz bilgiler sunar. Bizans kaynakları içinde kendine özgü özellikleri nedeniyle daha çok Bizans’ın “gayriresmi tarihyazımı” örnekleri sayılan kroniklerin büyük bölümü Bizans taşrasındaki manastırlarda yazılmıştır. İstanbul’un fethinden sonra da bir bölümü Osmanlı egemenliği veya tehdidi altındaki eski Bizans taşrasında yazılan kroniklerde, 14.yy’dan itibaren Yunanca konuşan Ortodoks Hristiyan toplumunun -

©Copyright 2018 Malkhaz Saldadze

©Copyright 2018 Malkhaz Saldadze Resources for Crafting Sovereignties in Breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Politics of Nationhood within the Rivalry between Russia and Georgia Malkhaz Saldadze A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Russia, Eastern Europe & Central Asia University of Washington 2018 Committee: Scott Radnitz Glennys Young Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies University of Washington ii Abstract Resources for Crafting Sovereignties in Breakaway Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Politics of Nationhood within the Rivalry between Russia and Georgia Malkhaz Saldadze Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Scott Radnitz Jackson School of International Studies This thesis is aimed at analysis of nation making in Georgia’s breakaway territories engaging certain aspects of foreign and domestic affairs that might be viewed as sources for crafting sovereignties in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. For this purpose, I deal with historiography and collective memory as a source of justification of secession and sovereignty, and relevant political interpretation of these discourses that have mobilizing effects in the respective societies. Demographic changes and politics of ethnic consolidation after the wars for independence in 1990s and Russian-Georgian war in 2008, and their influence on legitimacy of elites of the respective political entities, are also examined in order to gain more understanding of state building in Georgia’s breakaway republics. Russia’s efforts to support nation building in Abkhazia and South Ossetia through financial, human, symbolic-emotional and political investment is one more aspect brought into analysis. Overall goal for studying domestic and international resources of crafting polities in breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is to understand how these post-war iii societies construct their identities, institutions and statehood under influence of the contested geopolitical environment. -

Georgian Royal Dynasties and Issues of Political Inheritance in Medieval Georgia

Free University Journal of Asian Studies G. NARIMANISHVILI GEORGE NARIMANISHVILI FREE UNIVERSITY OF TBILISI [email protected] GEORGIAN ROYAL DYNASTIES AND ISSUES OF POLITICAL INHERITANCE IN MEDIEVAL GEORGIA Abstract According to the Georgian historical sources, during the transfer of royal power, the issue of inheritance was of special importance. Royal power usually passed from father to son. If the throne could not be handed over directly, the daughter’s rights would come to the fore. In this regard, the legal status of a woman member of the royal family is interesting. According to Georgian historical sources, women not only had hereditary property rights but also the right to inherit royal authority. Exactly according to this right, the royal government in Georgia has been legitimately transferred several times. One of the clearest examples of this is the enthronement of Mirian in Kartli. After marrying Abeshura, the daughter of the king of Kartli Asfaguri, he became the king of Kartli. As a result, the royal government has been transferred from wife to husband. This is how the kingship of the Parnavazian-Chosroid dynasty started in Kartli. Thus, Mirian and his successors became the political heirs of the Parnavazians. In the 6th century, the Bagrationi family appeared in the Georgian political arena and became actively involved in the struggle for the Georgian royal throne. After a long confrontation, at the turn of the 11th century, Bagrat III became the king of the united Georgian Kingdom. He was the political heir to both dynasties. He received the title of the king of Georgians from his father, and the Chosroid inheritance was again transferred by the line of a woman, and from Gurandukht, it passed to Bagrat.