The Prospects for Airports Ppps in Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping a Policy-Making Process the Case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia

THESIS REPORT Mapping a Policy-making Process The case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara MSc Tourism, Society & Environment Wageningen University and Research A Master’s thesis Mapping a policy-making process: the case of Komodo National Park, Indonesia Novalga Aniswara 941117015020 Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Supervisor: prof.dr. Edward H. Huijbens Examiner: dr. ir. Martijn Duineveld Wageningen University and Research Department of Environmental Science Cultural Geography Chair Group Master of Science in Tourism, Society and Environment i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Tourism has been an inseparable aspect of my life, starting with having a passion for travelling until I decided to take a big step to study about it back when I was in vocational high school. I would say, learning tourism was one of the best decisions I have ever made in my life considering opportunities and experiences which I encountered on the process. I could recall that four years ago, I was saying to myself that finishing bachelor would be my last academic-related goal in my life. However, today, I know that I was wrong. With the fact that the world and the industry are progressing and I raise my self-awareness that I know nothing, here I am today taking my words back and as I am heading towards the final chapter from one of the most exciting journeys in my life – pursuing a master degree in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Never say never. In completing this thesis, I received countless assistances and helps from people that I would like to mention. Firstly, I would not be at this point in my life without the blessing and prayers from my parents, grandma, and family. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online PT Pos Indonesia IDA ID

Parcel Post Compendium Online ID - Indonesia PT Pos Indonesia IDA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 30 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 30 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are No registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of -

Inaca White Paper

Universitas Padjadjaran INACA WHITE PAPER PROJECTED RECOVERY OF THE AVIATION INDUSTRY TOWARDS THE NEW NORMAL COOPERATION OF UNIVERSITAS PADJADJARAN (UNPAD) INACA Members INACA White Paper 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 LIST OF PICTURES .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 6 I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 II. HEALTH ASPECT ............................................................................................................................. .............................. 16 NATIONAL VACCINATION PROGRAM STRATEGY AND POLICY .......................................................... 16 Planning of COVID-19 Vaccination Needs ................................................................................................... 18 Target of the Implementation of the COVID-19 Vaccination ......................................................... -

CADP 2.0) Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation

The Comprehensive Asia Development Plan 2.0 (CADP 2.0) Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation November 2015 Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, its Governing Board, Academic Advisory Council, or the institutions and governments they represent. All rights reserved. Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted with proper acknowledgement. Cover Art by Artmosphere ERIA Research Project Report 2014, No.4 National Library of Indonesia Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN: 978-602-8660-88-4 Contents Acknowledgement iv List of Tables vi List of Figures and Graphics viii Executive Summary x Chapter 1 Development Strategies and CADP 2.0 1 Chapter 2 Infrastructure for Connectivity and Innovation: The 7 Conceptual Framework Chapter 3 The Quality of Infrastructure and Infrastructure 31 Projects Chapter 4 The Assessment of Industrialisation and Urbanisation 41 Chapter 5 Assessment of Soft and Hard Infrastructure 67 Development Chapter 6 Three Tiers of Soft and Hard Infrastructure 83 Development Chapter 7 Quantitative Assessment on Hard/Soft Infrastructure 117 Development: The Geographical Simulation Analysis for CADP 2.0 Appendix 1 List of Prospective Projects 151 Appendix 2 Non-Tariff Barriers in IDE/ERIA-GSM 183 References 185 iii Acknowledgements The original version of the Comprehensive Asia Development Plan (CADP) presents a grand spatial design of economic infrastructure and industrial placement in ASEAN and East Asia. Since the submission of such first version of the CADP to the East Asia Summit in 2010, ASEAN and East Asia have made significant achievements in developing hard infrastructure, enhancing connectivity, and participating in international production networks. -

Indonesia's Sustainable Development Projects

a INDONESIA’S SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS PREFACE Indonesia highly committed to implementing and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Under the coordination of the Ministry of National Development Planning/Bappenas, Indonesia has mainstreamed SDGs into National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) and elaborated in the Government Work Plan (RKP) annual budget documents. In its implementation, Indonesia upholds the SDGs principles, namely (i) universal development principles, (ii) integration, (iii) no one left behind, and (iv) inclusive principles. Achievement of the ambitious SDGs targets, a set of international commitments to end poverty and build a better world by 2030, will require significant investment. The investment gap for the SDGs remains significant. Additional long-term resources need to be mobilized from all resources to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In addition, it needs to be ensured that investment for the SDGs is inclusive and leaves no one behind. Indonesia is one of the countries that was given the opportunity to offer investment opportunities related to sustainable development in the 2019 Sustainable Development Goals Investment (SDGI) Fair in New York on April 15-17 2019. The SDGI Fair provides a platform, for governments, the private sectors, philanthropies and financial intermediaries, for “closing the SDG investment gap” through its focus on national and international efforts to accelerate the mobilization of sufficient investment for sustainable development. Therefore, Indonesia would like to take this opportunity to convey various concrete investment for SDGs. The book “Indonesia’s Sustainable Development Project” shows and describes investment opportunities in Indonesia that support the achievement of related SDGs goals and targets. -

Gudang Garam

Indonesia Company Focus Gudang Garam Bloomberg: GGRM IJ | Reuters: GGRM.JK Refer to important disclosures at the end of this report DBS Group Research . Equity 17 Jan 2019 Finance L.P. BUY Lighting up (Initiating Coverage) The biggest beneficiary of the improvement in consumption Last Traded Price ( 16 Jan 2019): Rp84,300 (JCI : 6,413.4) power and absence of excise tax hike in FY19F Price Target 12-mth: Rp94,700 (12% upside) Expect revenue and earnings to grow by 12%/33% in FY19F Volume growth would be driven by SKM FF segment Potential Catalyst: No cigarettes excise tax hike in FY19F, improvement Initiate with a BUY call; our preferred pick in the sector in consumption, and improvement in market share. Initiate coverage with a BUY call and TP of Rp94,700. We like Analyst GGRM as (i) a beneficiary of potential higher consumption power, David Arie Hartono +62 2130034936 [email protected] (ii) the absence of excise tax hike should improve its earnings in Price Relative FY19F, and (iii) its valuation looks attractive at 15.7x FY19F PE - Rp Relative Index with the strong improvement in profitability, working capital, and 91,005.0 market share; we believe that GGRM should continue to narrow its 209 81,005.0 189 valuation gap to HMSP (currently, the discount is at 45%). 71,005.0 169 Potentially higher demand for machine made full flavour cigarettes 61,005.0 149 129 (SKM FF) segment. In our view, the gradual improvement in 51,005.0 109 41,005.0 consumption purchasing power, especially in low to mid-level 89 31,005.0 69 income groups, would improve demand for higher tar cigarettes in Jan-15 Jan-16 Jan-17 Jan-18 Jan-19 the SKM FF segment (which is more favored by the low to mid- Gudang Garam (LHS) Relative JCI (RHS) income groups) rather than SPM or SKM LTN (low tar nicotine) Forecasts and Valuation which normally targets the mid to upper income groups. -

Airport Expansion in Indonesia

Aviation expansion in Indonesia Tourism,Aerotropolis land struggles, economic Update zones and aerotropolis projects By Rose Rose Bridger Bridger TWN Third World Network June 2017 Aviation Expansion in Indonesia Tourism, Land Struggles, Economic Zones and Aerotropolis Projects Rose Bridger TWN Global Anti-Aerotropolis Third World Network Movement (GAAM) Aviation Expansion in Indonesia: Tourism, Land Struggles, Economic Zones and Aerotropolis Projects is published by Third World Network 131 Jalan Macalister 10400 Penang, Malaysia www.twn.my and Global Anti-Aerotropolis Movement c/o t.i.m.-team PO Box 51 Chorakhebua Bangkok 10230, Thailand www.antiaero.org © Rose Bridger 2017 Printed by Jutaprint 2 Solok Sungai Pinang 3 11600 Penang, Malaysia CONTENTS Abbreviations...........................................................................................................iv Notes........................................................................................................................iv Introduction..............................................................................................................1 Airport Expansion in Indonesia.................................................................................2 Aviation expansion and tourism.........................................................................................2 Land rights struggles...........................................................................................................3 Protests and divided communities.....................................................................................5 -

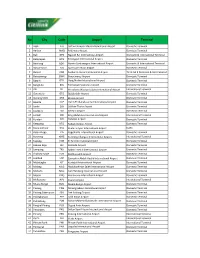

List Station Citilink Per 280720.Xlsx

NoCity Code Airport Terminal 1 Aceh BTJ Sultan Iskandar Muda International Airport Domestic Terminal 2Ambon AMQ Pamura Airport Domestic Terminal 3 Bali DPS Ngurah Rai International Airport Domestic & International Terminal 4 Balikpapan BPN Sepinggan International Airport Domestic Terminal 5 Bandung BDO Husein Sastranegara Internaonal Airport Domestic & International Terminal 6 Banjarmasin BDJ Syamsudin Noor Airport Domestic Terminal 7 Banten CGK Soekarno Hatta International Airport Terminal 3 Domestic & International 8 Banyuwangi BWX Banyuwangi Airport Domestic Terminal 9 Batam BTH Hang Nadim International Airport Domestic Terminal 10 Bengkulu BKS Fatmawati Soekarno Airport Domestic Terminal 11 Dili DIL Presidente Nicolau Lobato International Airport International Terminal 12 Gorontalo GTO Djalaluddin Airport Domestic Terminal 13 Gunung Sitoli GNS Binaka Airport Domestic Terminal 14 Jakarta HLP Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport Domestic Terminal 15 Jambi DJB Sulthan Thaha Airport Domestic Terminal 16 Jayapura DJJ Sentani Airport Domestic Terminal 17 Jeddah JED King Abdul Aziz International Airport International Terminal 18 Kendari KDI Haluileo Airport Domestic Terminal 19 Ketapang KTG Rahadi Osman Airport Domestic Terminal 20 Kuala Lumpur KUL Kuala Lumpur International Airport KLIA1 21 Kulon Progo YIA Yogyakarta International Airport Domestic Terminal 22 Kunming KMG Kunming Changsui International Airport International Terminal 23 Kupang KOE El Tari International Airport Domestic Terminal 24 Labuan Bajo LBJ Komodo Airport Domestic -

Ranaka Volcano Trekking & Komodo Tour

RANAKA VOLCANO TREKKING & KOMODO TOUR 5 DAYS / 4 NIGHTS Let us take you on an unforgettable journey around the magical island of Flores: volcanoes, traditional villages, rice fields and you will also have the chance to see Komodo dragons and enjoy marine life. Arrival flight : Labuanbajo Departure flight: Labuanbajo DAY 1: WELCOME TO LABUANBAJO-RUTENG Upon arrival at Komodo Airport of Labuan Bajo, meeting service with our local tour guide, and then drive to Ruteng via Lembor village. On the way will stop at several nice view point. Stop at Ciko Nobo view point and Lembor village for making picture of the view from the largest paddy fields in western Flores island. Continue driving to Ruteng for overnight stay at your chosen hotel. Meals included: --- DAY 2: RUTENG- RANAKA VOLCANO TREKKING – RUTENG Early morning around 05:00 AM after Get breakfast at your hotel then drive to starting point for trekking/climb to Ranaka volcano, it is take around 4 hour for one way, to day is half day trekking. Ranaka trekking as one of many active volcano on the island which is 2,400 meter above level and becoming the highest volcano on the island of Flores. The latest explosion of this volcano in 1987. Enjoy the spectacular landscape from the top of the mountain. Back to the hotel for lunch. Afterward will drive to Liang Bua cave the place where the fossils of Homo Floresiensis or nick name is Flores Hobbit was found the archeologist from Indonesia and Australia in 2003. After visiting the cave, the afternoon activity program is having soft trekking in the northern of Ruteng called Kilo Lima. -

Terus Melangkah Maju Menuju Masa Depan Yang Berkelanjutan Sustainable Progress Sustainable Future

TERUS MELANGKAH MAJU MENUJU MASA DEPAN YANG BERKELANJUTAN SUSTAINABLE PROGRESS SUSTAINABLE FUTURE 2020 Laporan Keberlanjutan Sustainability Report PT Solusi Bangun Indonesia Tbk TERUS MELANGKAH MAJU MENUJU MASA DEPAN YANG BERKELANJUTAN Industri bahan bangunan dan konstruksi tengah Sebagai perusahaan bahan bangunan, SBI berfokus mengalami perubahan dalam hal keberlanjutan. Banyak pada peningkatan berkelanjutan yang memotivasi perusahaan telah melihat manfaat dari berbagai semua sumber daya kami untuk menjadi lebih baik di pendekatan alternatif terhadap perbaikan jadwal, masa depan. Karenanya, kami berusaha keras untuk anggaran, dan kualitas serta nilai proyek secara membangun hubungan jangka panjang dengan para keseluruhan. Peningkatan kolaborasi ini merupakan pelanggan kami dengan menawarkan rangkaian produk kunci keberlanjutan utama bagi SBI, dan kemampuan dan layanan yang lengkap, serta membangun sumber untuk menjalankannya sebaik mungkin tidak hanya akan daya manusia berkualitas yang terspesialisasi dalam menguntungkan Perseroan, tetapi juga para pemangku menciptakan solusi inovatif. kepentingan kami. SUSTAINABLE PROGRESS SUSTAINABLE FUTURE The building material and construction industry is As a building and construction materials company, SBI changing, particularly in regards to its sustainability focuses on continuous improvement that motivates all aspects. A lot of companies has witnessed the of our resources to be better. To that end, we strive to benefit from the various alternative approaches in the nurture long-term relationship with our customers by improvement of timeliness, budget, quality, and the overall offering a wide-range of products and services, as well as value of their projects. On this note, stronger collaboration nurturing our people to be highly qualified personnel and is central for SBI’s sustainability strategy. Hence, our ability experts in creating innovative solutions. -

Gapura Annual Report 2017

2017 Laporan Tahunan Annual Report PERFORMANCE THROUGH SERVICE & OPERATIONS EXCELLENCE DAFTAR ISI Table of Contents PERFORMANCE THROUGH SERVICE & PEMBAHASAN DAN ANALISA MANAJEMEN OPERATIONS EXCELLENCE 1 Management Discussion & Analysis 56 Tinjauan Bisnis dan Operasional IKHTISAR 2017 Business & Operational Review 58 2017 Highlights 2 Tinjauan Pendukung Bisnis Business Support Review 64 Kinerja 2017 Tinjauan Keuangan 2017 Performance 2 Financial Review 80 Ikhtisar Keuangan Financial Highlights 4 TATA KELOLA PERUSAHAAN LAPORAN MANAJEMEN Corporate Governance 92 Management Report 6 Rapat Umum Pemegang Saham General Shareholders Meeting 103 Laporan Dewan Komisaris Dewan Komisaris Report from the Board of Commissioners 8 Board of Commissioners 104 Laporan Direksi Direksi Report from the Board of Directors 14 Board of Directors 109 Komite Audit PROFIL PERUSAHAAN Audit Committee 119 Company Profile 22 Sekretaris Perusahaan Identitas Perusahaan Corporate Secretary 121 Company Identity 24 Manajemen Risiko Sekilas Gapura Risk Management 126 Gapura in Brief 26 Kode Etik Perusahaan Visi dan Misi Company Code of Conduct 130 Vision & Mission 28 Komposisi Pemegang Saham TANGGUNG JAWAB SOSIAL PERUSAHAAN Shareholders Composition 30 Corporate Social Responsibility 136 Jejak Langkah Milestones 32 Bidang Usaha LAPORAN KEUANGAN Field of Business 36 Financial Statements 153 Produk dan Jasa Products & Services 38 DATA PERUSAHAAN Wilayah Operasi Corporate Data 207 Operational Area 40 Pertumbuhan GSE 2014-2018 Struktur Organisasi GSE Growth 2014-2018 208 Organizational -

Komodo National Park and Labuan Bajo (Flores) Baseline Demand & Supply, Market Demand Forecasts, and Investment Needs

KOMODO NATIONAL PARK AND LABUAN BAJO (FLORES) BASELINE DEMAND & SUPPLY, MARKET DEMAND FORECASTS, AND INVESTMENT NEEDS MARKET ANALYSIS AND DEMAND ASSESSMENTS TO SUPPORT THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTEGRATED TOURISM DESTINATIONS ACROSS INDONESIA WORLD BANK SELECTION # 1223583 (2016-2017) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS PREPARED BY: FOR: WITH SUPPORT FROM: This work is a product of external contributions supervised by The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. This publication has been funded by the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Swiss Confederation through the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO). The views expressed in this publication are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Australian Government and the Swiss Confederation. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 BASELINE DEMAND & SUPPLY .......................................................................................