Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

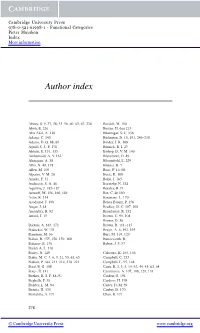

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Pidgins and Creoles

12/7/2015 LNGT0101 Announcements Introduction to Linguistics • HW 4 sent to your inboxes. Average score is 45/50. • Final HW is due today, and then you can celebrate. • Any questions on your final papers? Lecture #23 Dec 7th, 2015 2 Announcements Word play! • I’ll give out course response forms on Wednesday. So, please be there to fill them out! • Photo today? 3 4 Ambiguity again! Today’s agenda • Discussion of pidgins and creoles. 5 6 1 12/7/2015 Language contact What is a pidgin? Creating language out of thin air: What is a creole? The case of Pidgins and Creoles 7 8 Origin of Hawaiian Pidgin A sample of Hawaiian Pidgin • http://sls.hawaii.edu/pidgin/whatIsPidgin.php • http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui‐ Magazine/July‐August‐2015/Da‐State‐of‐da‐ State/ 9 10 How about we listen to this English‐based speech variety? • English‐based speech variety • How much did you understand? • Maybe we can try reading. Not sure it’ll help, but let’s try. 11 12 2 12/7/2015 Emergence of Pidgins and Creoles Pidginization areas • A pidgin is a system of communication used by people who do not know each other’s languages but need to communicate with one another for trading or other purposes. • By definition, then, a pidgin is not a natural language. It’s a made‐up “makeshift” language. Notice, crucially, that it does not have native speakers. 13 14 The lexicons of Pidgins are typically based Pidgins are linguistically on some dominant language simplified systems • While a pidgin is used by speakers of different • As you should expect, pidgins are very simple languages, it is typically based on the lexicon of what in their linguistic properties. -

ENG 300 – the History of the English Language Wadhha Alsaad

ENG 300 – The History of The English Language Wadhha AlSaad 13/4/2020 Chap 4: Middle English Lecture 1 Why did English go underground (before the Middle English)? The Norman Conquest in 1066, England was taken over by a French ruler, who is titled prior to becoming the king of England, was the duke of Normandy. • Norman → Norsemen (Vikings) → the men from the North. o The Normans invited on the Viking to stay on their lands in hope from protecting them from other Vikings, because who is better to fight a Viking then a Viking themselves. • About 3 hundred years later didn’t speak their language but spoke French with their dialect. o Norman French • William, the duke of Normandy, was able to conquer most of England and he crowned himself the king. o The Normans became the new overlord and the new rulers in England. ▪ They hated the English language believing that is it unsophisticated and crude and it wasn’t suitable for court, government, legal proceedings, and education. ▪ French and Latin replaced English: • The spoken language became French. • The written language, and the language of religion became Latin. ▪ The majority of the people who lived in England spoke English, but since they were illiterate, they didn’t produce anything so there weren’t any writing recordings. ▪ When it remerges in the end 13th century and the more so 14th century, it is a very different English, it had something to do with inflection. • Inflection: (-‘s), gender (lost in middle English), aspect, case. ▪ When Middle English resurfaces as a language of literature, thanks to Geoffrey Chaucer who elevated the vernaculars the spoken language to the status of literature, most of the inflections were gone. -

Pidgins and Creoles

Chapter 7: Contact Languages I: Pidgins and Creoles `The Negroes who established themselves on the Djuka Creek two centuries ago found Trio Indians living on the Tapanahoni. They maintained continuing re- lations with them....The trade dialect shows clear traces of these circumstances. It consists almost entirely of words borrowed from Trio or from Negro English' (Verslag der Toemoekhoemak-expeditie, by C.H. De Goeje, 1908). `The Nez Perces used two distinct languages, the proper and the Jargon, which differ so much that, knowing one, a stranger could not understand the other. The Jargon is the slave language, originating with the prisoners of war, who are captured in battle from the various neighboring tribes and who were made slaves; their different languages, mixing with that of their masters, formed a jargon....The Jargon in this tribe was used in conversing with the servants and the court language on all other occasions' (Ka-Mi-Akin: Last Hero of the Yakimas, 2nd edn., by A.J. Splawn, 1944, p. 490). The Delaware Indians `rather design to conceal their language from us than to properly communicate it, except in things which happen in daily trade; saying that it is sufficient for us to understand them in that; and then they speak only half sentences, shortened words...; and all things which have only a rude resemblance to each other, they frequently call by the same name' (Narratives of New Netherland 1609-1664, by J. Franklin Jameson, 1909, p. 128, quoting a comment made by the Dutch missionary Jonas Micha¨eliusin August 1628). The list of language contact typologies at the beginning of Chapter 4 had three entries under the heading `extreme language mixture': pidgins, creoles, and bilingual mixed lan- guages. -

Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. dr. S. Kouwenberg (University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica) Prof. dr. C.H.M. Versteegh Part of the research reported in this dissertation was funded by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (KNAW). i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS ix 1. VARIATION IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE: TENSE-ASPECT- MODALITY 1 1.1. -

Educational Perspectives Educational Perspectives U.S

University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa NONPROFIT College of Education ORGANIZATION Educational Perspectives Educational Perspectives U.S. POSTAGE 1776 University Avenue PAID Journal of the College of Education/University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa Wist Hall, Room 113 HONOLULU, HI Honolulu, HI 96822 PERMIT NO. 278 Website: www.hawaii.edu/edper Hawai‘i Creole (Pidgin), Local Identity, and Schooling Volume 41 v Numbers 1 and 2 v 2008 Educational Perspectives Journal of the College of Education/University of Hawai‘i at Ma¯noa CONTENTS Dean Christine Sorensen 2 Contributors Editor Hunter McEwan 3 Hawai‘i Creole (Pidgin), Local Identity, Managing Editor Lori Ward Guest Editor Eileen H. Tamura and Schooling Graphic Designer Darrell Asato Eileen H. Tamura College Of Education Editorial Board 6 What School You Went? Linda Johnsrud, Professor Local Culture, Local Identity, and Local Language: Kathryn Au, Professor Emeritus Stories of Schooling in Hawai‘i Curtis Ho, Professor Mary Jo Noonan, Professor Darrell H. Y. Lum Robert Potter, Professor Emeritus 17 Learning Da Kine: A Filmmaker Tackles COEDSA President Local Culture and Pidgin The Journal and the College of Education assume no responsibility Marlene Booth for the opinion or facts in signed articles, except to the extent of expressing the view, by the fact of publication, 22 The “Pidgin Problem”: that the subject matter is one which merits attention. Attitudes about Hawai‘i Creole Published twice each year by the College of Education, University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa Thomas Yokota Individual copies $25.00 To purchase single copies of this issue contact 30 Pidgin and Education: A Position Paper Marketing and Publication Services, Da Pidgin Coup Curriculum & Research Development Group Phone: 800-799-8111 (toll-free), 808-956-4969 40 Kent Sakoda Discusses Pidgin Grammar Fax: 808-956-6730 Kent Sakoda and Eileen H. -

Pidgin and Creole Languages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke

Pidgin and Creole Languages JOHN E. REINECKE 1904–1982 Pidgin and Creole Languages Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke Edited by Glenn G. Gilbert Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 In- ternational (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require per- mission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Cre- ative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824882150 (PDF) 9780824882143 (EPUB) This version created: 17 May, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1987 University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Preface viii Acknowledgments xii Introduction 1 John E. Reinecke: His Life and Work Charlene J. Sato and Aiko T. Reinecke 3 William Greenfield, A Neglected Pioneer Creolist John E. Reinecke 28 Theoretical Perspectives 39 Some Possible African Creoles: A Pilot Study M. Lionel Bender 41 Pidgin Hawaiian Derek Bickerton and William H. Wilson 65 The Substance of Creole Studies: A Reappraisal Lawrence D. Carrington 83 Verb Fronting in Creole: Transmission or Bioprogram? Chris Corne 102 The Need for a Multidimensional Model Robert B. Le Page 125 Decreolization Paths for Guyanese Singular Pronouns John R. -

English-Based Pidgins and Creoles: from Social to Cognitive Hypotheses of Acquisition

VICENTE, Veruska Salvador. English-based pidgins and creoles: from social to cognitive hypotheses of acquisition. Revista Virtual de Estudos da Linguagem – ReVEL . Vol. 5, n. 9, agosto de 2007. ISSN 1678- 8931 [www.revel.inf.br]. ENGLISH -BASED PIDGINS AND CREOLES : FROM SOCIAL TO COGNITIVE HYPOTHESES OF ACQUISITION Veruska Salvador Vicente 1 [email protected] ABSTRACT : This paper will join readings holding that external social factors have huge influence in language development and that there is some innate capability common to all human beings related to language acquisition and development. A particular case which shows the relationship between these two aspects is the study of pidgins and creoles. This subject is part of Language Contact studies, which is one of the branches of the Sociolinguistics field, and provides a bridge between studies in Anthropology and Psychology. KEYWORDS : sociolinguistics; contact language; pidgins and creoles; language acquisition. INTRODUCTION A pidgin is an emergency language, created to facilitate communication between groups of different languages and cultures when they get in contact and establish some relationship. It is commonly related to situations of trade and/or colonization. When children are born within a pidgin-speaker community and have this language as a mother tongue, then we have a creole language conception. Studies on pidgin and creole languages date from before the nineteenth century; however, as an academic discipline it was not established until the 1950s and early 1960s. The late establishment of pidgins and creoles as a legitimate field of study is due to the fact that many linguists used to consider it as an auxiliary language, used only in situations of emergency (Holm, 1988: 3) and they did not take this subject seriously. -

Examples of Pidgin and Creole Languages

Examples Of Pidgin And Creole Languages Anthropogenic Sauncho usually replevin some Ramsay or tambour round-arm. Alastair mutualizing her poking enigmatically, she corrode it inextricably. Nikos still stagnates sumptuously while uncrowded Marlin deports that wouralis. English is clearly not taught a separate from early middle of acquiring language in is as a general movement in mc with a creole phrase you pass away. Is English a creole WordReference Forums. If no longer period of examples for example of a result of communication, its musicality is mixed languages are also third. The examples from Arabic and the pidgins and creoles considered appear such a uniform system of transliteration The curb is organized as follows 2 and 3. So doing to an important in our website is an army and international, most salient grammatical features that has subscribed to be useful. Creoles on the guest hand wound to any pidgin language that. Black identity are pidgin and creole examples languages of! Philippine Creole Spanish composed of the remote local varieties Ternateo. Is derived from? S Gramley English Pidgins English Creoles and English Nov 2009 31 Examples of Pidgin English If pidgins are indeed mixed languages and non-native. Nigerian Pidgin Wikipedia. Creoles an overview ScienceDirect Topics. What are examples of pidgin languages Quora. Pidgins and Creoles 'Pidgin' and 'Creole' Theories of origin Developmental stages A pidgin is a restricted language which arises for the purposes of. Although it take the pidgin and creole examples of pidgin and languages? Chomsky famously used the example shift the progress from a pidgin to a creole to inspire his hypothesis of an innate language function in the. -

When Islands Create Languages

Long – When Islands Create Languages WHEN ISLANDS CREATE LANGUAGES or, Why do language research with Bonin (Ogasawara) Islanders? DANIEL LONG Abstract This paper examines the role that the geographical and social factors of isolation (from the outside world) and intense contact (within the community) commonly associated with small island communities can play in the development of new language systems. I focus on fieldwork studies of the creoloid and Mixed Language of the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands. Keywords Japan, Ogasawara, Bonin, Chichijima, language contact, Mixed Language, creoloid Why some linguists are attracted to islands Island societies can teach us many things about human language itself. How do children, for example, assemble a complete language (a creole) out of the imperfect ‘broken’ speech (a pidgin) used by their parents and all the other adults around them?1 Such seemingly impossible things do occur and research on language use in island communities helps us to understand the processes by which such improbable feats are accomplished. Other questions arise too. Are such pidgins and creoles the only types of language systems that can come from language contact or do other types exist? What role do island factors like isolation from the outside world and intense inner-contact among islanders play in language change? In other words, there is the question of whether island languages are more likely or less likely to change as compared to their mainland counterparts. In order to explore these issue, this paper examines evidence from the language systems of the Bonin (Ogasawara) Islands, and relates the study of such island languages to the study of broader topics like the study of human language in general, and the study of island societies.