Pidgins and Creoles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirits of Our Whaling Ancestors

Spirits of Our Whaling Ancestors SpiritS of our Whaling anceStorS Revitalizing Makah and Nuu-chah-nulth Traditions charlotte coté Foreword by MiCah MCCarty A Capell Family Book University of Washington Press Seattle & London UBC Press Vancouver & Toronto the CaPell faMily endoWed Book Fund supports the publication of books that deepen the understanding of social justice through historical, cultural, and environmental studies. Preference is given to books about the American West and to outstanding first books in order to foster scholarly careers. © 2010 by the University of Washington Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publica- Printed in the United States of America tion Data and Library and Archives Canada Design by Thomas Eykemans Cataloging in Publication can be found at the 15 14 13 12 11 10 5 4 3 2 1 end of the book. All rights reserved. No part of this publica- The paper used in this publication is acid-free tion may be reproduced or transmitted in and 90 percent recycled from at least 50 per- any form or by any means, electronic or cent post-consumer waste. It meets the mini- mechanical, including photocopy, record- mum requirements of American National ing, or any information storage or retrieval Standard for Information Sciences—Perma- system, without permission in writing from nence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, the publisher. ANSI Z39.48–1984.∞ Published in the United States of America by frontisPieCe: Whaler photograph by University of Washington Press Edward S. Curtis; Courtesy Royal British P.o. Box 50096, Seattle, Wa 98145 U.s.a. Columbia Museum, Victoria. www.washington.edu/uwpress Published in Canada by UBC Press University of British Columbia 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, B.C. -

Language Creativity: a Sociolinguistic Reading of Linguistic Change in Lebanon

BAU Journal - Society, Culture and Human Behavior Volume 1 Issue 1 ISSN: 2663-9122 Article 2 August 2019 LANGUAGE CREATIVITY: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC READING OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE IN LEBANON Sawsan Tohme English Department, Faculty of Human Sciences, Beirut Arab University, Lebanon, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bau.edu.lb/schbjournal Part of the Architecture Commons, Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tohme, Sawsan (2019) "LANGUAGE CREATIVITY: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC READING OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE IN LEBANON," BAU Journal - Society, Culture and Human Behavior: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.bau.edu.lb/schbjournal/vol1/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ BAU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BAU Journal - Society, Culture and Human Behavior by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ BAU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE CREATIVITY: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC READING OF LINGUISTIC CHANGE IN LEBANON Abstract Language creativity in incorporated in everyday conversations and language behaviour. It is present in everyday expression although it might sometimes be invisible, looked down on or disdained. Regardless of whether we are in favour of or against this creativity, it is worth being recognised. As far as Lebanon is concerned, Arabic (i.e. Standard Arabic) is the official language, while Lebanese abic,Ar along with English and French, are the main languages used by the Lebanese. This language diversity can be explained in the light of a number of factors and sociolinguistic functions. -

An Early St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon Bilingual' Text 1 Introduction 1 2 About the Newspaper

"Fox and Cayooty": an early St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon bilingual' text Henry Davis and David Robertson University of British Columbia and CHINOOK List This paper contains a transliteration (from the original Duployan shorthand) and . translation of an early bilingual St'at'imcets-Chinook Jargon text, with accompanying historical, orthographical and grammatical notes. The story was first published in 1892 in the Kamloops Wawa newspaper by the oblate priest J-M.R. Le Jeune; it thus counts as one of the earliest texts in either language. 1 Introduction 1 It is well known to the student of Salishan languages and cultures that before the time of Franz Boas, extremely few coherent texts, as opposed to relatively numerous fragmentary word-lists, of northwest Native American languages were collected and published. The nascent modern disciplines of anthropology and linguistics demanded such documentation. However, another force besides science played a considerable role in the earliest recordings of indigenous languages of this region: The activities of Christian missionaries, which led to work allowing in some cases (viz. Joseph Giorda, S1's 1871 dictionary of Kalispel) an excellent view of historical stages in the lives of these languages otherwise lost to us.2 An example of the same phenomenon is available to us also in the Kamloops Wawa newspaper published by Oblate father J.-M.R. Le Jeune from 1891 to about 19043, primarily in the Chinook Jargon, of which it is an extensive and often overlooked document. In volume 2, Issue 47 of Kamloops Wawa, dated October 16 [sic], 18924, we find under the English heading "Recreative" the following: Kopa Pavilion ilihi nsaika tlap ukuk hloima syisim kopa Lilwat wawa[:] Fox and Cayooty.~. -

The Case of Nominal Plural Marking in Zamboanga Chabacano

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 19 Documentation and Maintenance of Contact Languages from South Asia to East Asia ed. by Mário Pinharanda-Nunes & Hugo C. Cardoso, pp.141–173 http:/nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp19 4 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24908 Documenting online writing practices: The case of nominal plural marking in Zamboanga Chabacano Eduardo Tobar Delgado Universidade de Vigo Abstract The emergence of computer-mediated communication has brought about new opportunities for both speakers and researchers of minority or under-described languages. This paper shows how the analysis of spontaneous contemporary language samples from online social networks can make a contribution to the documentation and description of languages like Chabacano, a Spanish-derived creole spoken in the Philippines. More specifically, we focus on nominal plural marking in the Zamboangueño variety, a still imperfectly understood feature, by examining a corpus composed of texts from online sources. The attested combination of innovative and vestigial features requires a close look at the high contact environment, different levels of metalinguistic awareness or even some language ideologies. The findings shed light on the wide variety of plural formation strategies which resulted from the contact of Spanish with Philippine languages. Possible triggers, such as animacy, definiteness or specificity, are also examined and some future research areas suggested. Keywords: nominal plural marking, Zamboangueño Chabacano, number, creole languages Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License 142 Eduardo Tobar Delgado 1. Introduction1 Zamboanga Chabacano (also known as Zamboangueño or Chavacano) is one of the three extant varieties of Philippine Creole Spanish or Chabacano and totals around 500,000 speakers in and around Zamboanga City in the Southern Philippines. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

Linguistics 181: SENĆOŦEN Fall 2010 Leonard and Werle 3 Handout 2

Linguistics 181: SENĆOŦEN Fall 2010 Leonard and Werle Handout 2: Language families of British Columbia Terminology ‣ language : a natural system of human communication that includes sounds, words, and rules for combining these to express a variety of meanings. ‣ native language , first language : a language that one speaks from a very young age. ‣ indigenous , aboriginal : these terms refer to people or languages that live in or are associated with a particular place, are the first or among the first to be associated with that place, and have historical and cultural roots from that place. ‣ dialect : a regional or social variety of a language. Everyone speaks a dialect! ‣ idiolect : the speech variety of a particular person. One’s individual dialect. ‣ jargon : vocabulary associated with a particular activity (example: carvers’ jargon). ‣ pidgin : a simplified language used by speakers of different languages to communicate (example: Chinook Jargon). No one’s native language. ‣ creole : a pidgin that has developed into a full language (example: Hawaiian Creole). ‣ language family : a group of languages whose similarities indicate that they come from a common parent language. Such languages are said to be genetically related (whether or not the speakers of these languages are related by blood). ‣ language area ( Sprachbund ): a group of languages whose similarities result from geographical contact. Such languages may or may not be genetically related. Notes The aboriginal languages of British Columbia form about seven language families (see map). SENĆOŦEN, or Saanich, is a member of the Salish family. language family examples ‣ Algonquian Cree, Ojibway ‣ Haida X̱aad Kil, X̱aaydaa Kil ‣ Kutenai Ktunaxa ‣ Na-Dene Nicola, Tsilhqot’in, Dakelh, Łingít ‣ Salishan SENĆOŦEN, Halq’eméylem, Secwepemctsin, Nuxalk ‣ Tsimshianic S’m̓algya̱x, Nisg ̱a’a ‣ Wakashan Nuu-chah-nulth, Kwak wala,̓ Haisla Salish is one of the largest indigenous language families of North America, in terms of number of languages. -

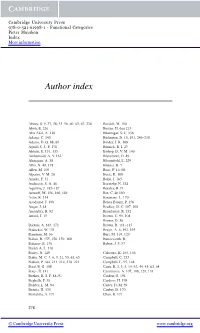

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Making Sense of "Bad English"

MAKING SENSE OF “BAD ENGLISH” Why is it that some ways of using English are considered “good” and others are considered “bad”? Why are certain forms of language termed elegant, eloquent, or refined, whereas others are deemed uneducated, coarse, or inappropriate? Making Sense of “Bad English” is an accessible introduction to attitudes and ideologies towards the use of English in different settings around the world. Outlining how perceptions about what constitutes “good” and “bad” English have been shaped, this book shows how these principles are based on social factors rather than linguistic issues and highlights some of the real-life consequences of these perceptions. Features include: • an overview of attitudes towards English and how they came about, as well as real-life consequences and benefits of using “bad” English; • explicit links between different English language systems, including child’s English, English as a lingua franca, African American English, Singlish, and New Delhi English; • examples taken from classic names in the field of sociolinguistics, including Labov, Trudgill, Baugh, and Lambert, as well as rising stars and more recent cutting-edge research; • links to relevant social parallels, including cultural outputs such as holiday myths, to help readers engage in a new way with the notion of Standard English; • supporting online material for students which features worksheets, links to audio and news files, further examples and discussion questions, and background on key issues from the book. Making Sense of “Bad English” provides an engaging and thought-provoking overview of this topic and is essential reading for any student studying sociolinguistics within a global setting. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

'Speaking Singlish' Comic Strips

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 12, 2020 The Use of Colloquial Singaporean English in ‘Speaking Singlish’ Comic Strips: A Syntactic Analysis Delianaa*, Felicia Oscarb, a,bEnglish department, Faculty of Cultural Studies, Universitas Sumatera Utara, Email: a*[email protected] This study explores the sentence structure of Colloquial Singaporean English (CSE) and how it differs from Standard English (SE). A descriptive qualitative method is employed as the research design. The data source is the dialogue of five comic strips which are purposively chosen from Speaking Singlish comic strips. Data is in the form of sentences totalling 34 declaratives, 20 wh- interrogatives, 14 yes -no interrogatives, 3 imperatives and 1 exclamative. The results present the sentence structure of CSE found in the data generally constructed by one subject, one predicate, and occasionally one discourse element. The subject is a noun phrase while the predicate varies amongst noun, adjective, adverb, and verb phrases– particularly in copula deletion. On the other hand, there are several differences between the sentence structure of CSE and SE in the data including the use of copula, topic sentence, discourse elements, adverbs, unmarked plural noun and past tense. Key words: Colloquial Singaporean English (CSE), Speaking Singlish, sentence structure. Introduction Standard English (SE) is a variety of the English language. This view is perhaps more acceptable in the case of Non-Standard English (NSE). The classification of SE being a dialect goes against the lay understanding that a dialect is a subset of a language, usually with a geographical restriction regarding its distribution (Kerswill, 2006). -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Journal of Postcolonial Writing the Field of Pidgin

This article was downloaded by: [Stanford University] On: 3 June 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 731786911] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Postcolonial Writing Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713735330 The field of Pidgin-Creole studies: A review article on Loreto Todd's Pidgins and Creoles. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974 John Rickforda a University of Guyana, To cite this Article Rickford, John(1977) 'The field of Pidgin-Creole studies: A review article on Loreto Todd's Pidgins and Creoles. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1974', Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 16: 2, 477 — 513 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/17449857708588494 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17449857708588494 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.