English-Based Pidgins and Creoles: from Social to Cognitive Hypotheses of Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portuguese Languagelanguage Kitkit

PortuguesePortuguese LanguageLanguage KitKit Expressions - Grammar - Online Resources - Culture languagecoursesuk.co.uk Introduction Whether you plan to embark on a new journey towards learning Portuguese or you just need a basic reference booklet for a trip abroad, the Cactus team has compiled some of the most help- ful Portuguese expressions, grammar rules, culture tips and recommendations. Portuguese is one the most significant languages in the world, and Portugal and Brazil are popular desti- nations for holidays and business trips. As such, Portuguese is appealing to an ever-growing number of Cactus language learners. Learning Portuguese will be a great way to discover the fascinating cultures and gastronomy of the lusophone world, and to improve your career pros- pects. Learning Portuguese is the beginning of an exciting adventure that is waiting for you! The Cactus Team 3. Essential Expressions Contact us 4. Grammar and Numbers Telephone (local rate) 5. Useful Verbs 0845 130 4775 8. Online Resources Telephone (int’l) 10. Take a Language Holiday +44 1273 830 960 11. Cultural Differences Monday-Thursday: 9am-7pm 12. Portugal & Brazil Culture Friday: 9am-5pm Recommendations 15. Start Learning Portuguese 2 Essential Expressions Hello Olá (olah) Goodbye Tchau (chaoh) Please Por favor Thank you Obrigado (obrigahdu) Yes Sim (simng) No Não (nowng) Excuse me/sorry Desculpe / perdão (des-cool-peh) My name is… O meu nome é… (oh meoh nomay ay) What is your name? Qual é o seu nome? (kwah-ooh eh seh-ooh noh-mee) Nice to meet you Muito prazer -

First Hundred Words in Portuguese Ebook

FIRST HUNDRED WORDS IN PORTUGUESE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Heather Amery,Stephen Cartwright | 32 pages | 01 Aug 2015 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9781474903684 | English | London, United Kingdom First Hundred Words in Portuguese PDF Book Portuguese uses a dot to separate thousands, eg. If you like this site and find it useful, you can support it by making a donation via PayPal or Patreon , or by contributing in other ways. You'll receive an invitation by email when the next registration period opens for new students. For instance, "immediately" in Portuguese is "imediatamente"; "automatically" in Portuguese is "automaticamente"; "basically" is "basicamente", and so on. Rafa x Go to top of the page. These words are very important because, in many cases, one word can be used in different situations, with different meanings. The second thing to think about is pronunciation. And yes, now, go to the streets and start asking people questions in Portuguese! European Portuguese. Portuguese Numbers. Anything to help us true beginners get our toe into the language is a huge help. Before you start learning Portuguese, you might have thought of how much Portuguese vocabulary you need. Register Now. Interrogatives are the question-words. Here we are using the word "time", but what we really mean is "this turn, i'm going by car". For more about these programs, see Technical help. Sound files should play on a computer, tablet or smartphone. Even if nobody understands you in case you are in a non-Portuguese speaking country , at least you are practising by saying it aloud! You don't need to know many of them. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

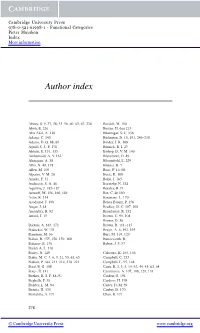

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

Following the Trail of the Snake: a Life History of Cobra Mansa “Cobrinha” Mestre of Capoeira

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FOLLOWING THE TRAIL OF THE SNAKE: A LIFE HISTORY OF COBRA MANSA “COBRINHA” MESTRE OF CAPOEIRA Isabel Angulo, Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Directed By: Dr. Jonathan Dueck Division of Musicology and Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Maryland Professor John Caughey American Studies Department, University of Maryland This dissertation is a cultural biography of Mestre Cobra Mansa, a mestre of the Afro-Brazilian martial art of capoeira angola. The intention of this work is to track Mestre Cobrinha’s life history and accomplishments from his beginning as an impoverished child in Rio to becoming a mestre of the tradition—its movements, music, history, ritual and philosophy. A highly skilled performer and researcher, he has become a cultural ambassador of the tradition in Brazil and abroad. Following the Trail of the Snake is an interdisciplinary work that integrates the research methods of ethnomusicology (oral history, interview, participant observation, musical and performance analysis and transcription) with a revised life history methodology to uncover the multiple cultures that inform the life of a mestre of capoeira. A reflexive auto-ethnography of the author opens a dialog between the experiences and developmental steps of both research partners’ lives. Written in the intersection of ethnomusicology, studies of capoeira, social studies and music education, the academic dissertation format is performed as a roda of capoeira aiming to be respectful of the original context of performance. The result is a provocative ethnographic narrative that includes visual texts from the performative aspects of the tradition (music and movement), aural transcriptions of Mestre Cobra Mansa’s storytelling and a myriad of writing techniques to accompany the reader in a multi-dimensional journey of multicultural understanding. -

Portuguese (PORT) 1

Portuguese (PORT) 1 PORTUGUESE (PORT) PORT 53: Intermediate Intensive Portuguese for Graduate Students 3 Credits PORT 1: Elementary Portuguese I Continued intensive study of Portuguese at the intermediate level: 4 Credits reading, writing, speaking, listening, cultural contexts. PORT 053 Intermediate Intensive Portuguese for Graduate Students (3)This is For beginners. Grammar, with reading and writing of simple Portuguese; the third in a series of three courses designed to give students an oral and aural work stressed. intermediate intensive knowledge of Portuguese. Continued intensive study of Portuguese at the intermediate level: reading, writing, speaking, Bachelor of Arts: 2nd Foreign/World Language (All) listening, and cultural contexts. Lessons are taught in an authentic PORT 2: Elementary Portuguese II cultural context. 4 Credits Prerequisite: PORT 052 or equivalent, and graduate standing Grammar, reading, and conversation continued; special emphasis on the PORT 123: Portuguese for Romance-language Speakers language, literature, and life of Brazil. 2-3 Credits Prerequisite: PORT 001 This course offers an introduction to Brazilian Portuguese for students Bachelor of Arts: 2nd Foreign/World Language (All) who already have a good grasp of grammar and vocabulary in Spanish, PORT 3: Intermediate Portuguese French, Italian, or Latin. This intensive course will address all four language skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) and provide 4 Credits an overall view of Portuguese, its basic linguistic structures, and vocabulary. Emphasis will be placed especially on the differences Grammar, reading, composition, and conversation. between Portuguese and Spanish. By building on students' prior knowledge of Romance languages, the class moves quickly to cover Prerequisite: PORT 002 the content of the three-semester basic language sequence in a single Bachelor of Arts: 2nd Foreign/World Language (All) semester. -

Redalyc.Portuguese-Japanese Language Contact in 16Th Century

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Kono, Akira Portuguese-Japanese language contact in 16th Century Japan Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, núm. 3, december, 2001, pp. 43 - 51 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100304 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2001, 3, 43 - 51 PORTUGUESE-JAPANESE LANGUAGE CONTACT IN 16th CENTURY JAPAN Akira Kono Osaka University of Foreign Studies The aim of this paper is twofold. The first section of the paper outlines the three different stages of Portuguese-Japanese language contact. The second section will discuss the etymology of one of the loanwords which presumably entered Portuguese lexicon from Japanese in the first stage of Portuguese- Japanese language contact, namely, bonzo, which has traditionally provoked some controversy as to its etymon. As we will see in the discussion of the third stage of Portuguese-Japanese language contact, it is rather straightforward to settle the problem of etymon in recent borrowing. However, attention must be paid to diachronic studies of Sixteenth Century Japanese, in the first stage of Portuguese-Japanese language contact, in order to solve the problem of the etymology of Japanese loanwords. 1. Historically, there are three stages of Portuguese-Japanese language contact. The first stage occurred in Sixteenth Century Japan. -

Hunsrik-Xraywe.!A!New!Way!In!Lexicography!Of!The!German! Language!Island!In!Southern!Brazil!

Dialectologia.!Special-issue,-IV-(2013),!147+180.!! ISSN:!2013+2247! Received!4!June!2013.! Accepted!30!August!2013.! ! ! ! ! HUNSRIK-XRAYWE.!A!NEW!WAY!IN!LEXICOGRAPHY!OF!THE!GERMAN! LANGUAGE!ISLAND!IN!SOUTHERN!BRAZIL! Mateusz$MASELKO$ Austrian$Academy$of$Sciences,$Institute$of$Corpus$Linguistics$and$Text$Technology$ (ICLTT),$Research$Group$DINAMLEX$(Vienna,$Austria)$ [email protected]$ $ $ Abstract$$ Written$approaches$for$orally$traded$dialects$can$always$be$seen$controversial.$One$could$say$ that$there$are$as$many$forms$of$writing$a$dialect$as$there$are$speakers$of$that$dialect.$This$is$not$only$ true$ for$ the$ different$ dialectal$ varieties$ of$ German$ that$ exist$ in$ Europe,$ but$ also$ in$ dialect$ language$ islands$ on$ other$ continents$ such$ as$ the$ Riograndese$ Hunsrik$ in$ Brazil.$ For$ the$ standardization$ of$ a$ language$ variety$ there$ must$ be$ some$ determined,$ general$ norms$ regarding$ orthography$ and$ graphemics.!Equipe!Hunsrik$works$on$the$standardization,$expansion,$and$dissemination$of$the$German$ dialect$ variety$ spoken$ in$ Rio$ Grande$ do$ Sul$ (South$ Brazil).$ The$ main$ concerns$ of$ the$ project$ are$ the$ insertion$of$Riograndese$Hunsrik$as$official$community$language$of$Rio$Grande$do$Sul$that$is$also$taught$ at$school.$Therefore,$the$project$team$from$Santa$Maria$do$Herval$developed$a$writing$approach$that$is$ based$on$the$Portuguese$grapheme$inventory.$It$is$used$in$the$picture$dictionary! Meine!ëyerste!100! Hunsrik! wërter$ (2010).$ This$ article$ discusses$ the$ picture$ dictionary$ -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Pidgins and Creoles

12/7/2015 LNGT0101 Announcements Introduction to Linguistics • HW 4 sent to your inboxes. Average score is 45/50. • Final HW is due today, and then you can celebrate. • Any questions on your final papers? Lecture #23 Dec 7th, 2015 2 Announcements Word play! • I’ll give out course response forms on Wednesday. So, please be there to fill them out! • Photo today? 3 4 Ambiguity again! Today’s agenda • Discussion of pidgins and creoles. 5 6 1 12/7/2015 Language contact What is a pidgin? Creating language out of thin air: What is a creole? The case of Pidgins and Creoles 7 8 Origin of Hawaiian Pidgin A sample of Hawaiian Pidgin • http://sls.hawaii.edu/pidgin/whatIsPidgin.php • http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui‐ Magazine/July‐August‐2015/Da‐State‐of‐da‐ State/ 9 10 How about we listen to this English‐based speech variety? • English‐based speech variety • How much did you understand? • Maybe we can try reading. Not sure it’ll help, but let’s try. 11 12 2 12/7/2015 Emergence of Pidgins and Creoles Pidginization areas • A pidgin is a system of communication used by people who do not know each other’s languages but need to communicate with one another for trading or other purposes. • By definition, then, a pidgin is not a natural language. It’s a made‐up “makeshift” language. Notice, crucially, that it does not have native speakers. 13 14 The lexicons of Pidgins are typically based Pidgins are linguistically on some dominant language simplified systems • While a pidgin is used by speakers of different • As you should expect, pidgins are very simple languages, it is typically based on the lexicon of what in their linguistic properties. -

ENG 300 – the History of the English Language Wadhha Alsaad

ENG 300 – The History of The English Language Wadhha AlSaad 13/4/2020 Chap 4: Middle English Lecture 1 Why did English go underground (before the Middle English)? The Norman Conquest in 1066, England was taken over by a French ruler, who is titled prior to becoming the king of England, was the duke of Normandy. • Norman → Norsemen (Vikings) → the men from the North. o The Normans invited on the Viking to stay on their lands in hope from protecting them from other Vikings, because who is better to fight a Viking then a Viking themselves. • About 3 hundred years later didn’t speak their language but spoke French with their dialect. o Norman French • William, the duke of Normandy, was able to conquer most of England and he crowned himself the king. o The Normans became the new overlord and the new rulers in England. ▪ They hated the English language believing that is it unsophisticated and crude and it wasn’t suitable for court, government, legal proceedings, and education. ▪ French and Latin replaced English: • The spoken language became French. • The written language, and the language of religion became Latin. ▪ The majority of the people who lived in England spoke English, but since they were illiterate, they didn’t produce anything so there weren’t any writing recordings. ▪ When it remerges in the end 13th century and the more so 14th century, it is a very different English, it had something to do with inflection. • Inflection: (-‘s), gender (lost in middle English), aspect, case. ▪ When Middle English resurfaces as a language of literature, thanks to Geoffrey Chaucer who elevated the vernaculars the spoken language to the status of literature, most of the inflections were gone.