Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistics 101 African American English AAE - Basics

Linguistics 101 African American English AAE - Basics • AAE = AAVE (African American Vernacular English) • AAE is a dialect continuum • ranges from Standard American English spoken with a AAE accent to the Gullah creole like that spoken off the coast of Georgia. • AAE is neither spoken by all African Americans, nor is it spoken by only African Americans. • Most speakers of AAE are bidialectal. AAE - Basics • Why focus on AAE? 1. Case study for the relation between a society and language. 2. Many misconceptions exist, more so than with other dialects. AAE - Misconceptions • Common misconceptions: • AAE is just slang • AAE is bad English • AAE is illogical • ... • There is no scientific basis for the above misconception. • Like Standard American English (SAE), AAE has: • a grammar • a lexicon • social rules of use AAE - Misconceptions • Reasons for misconceptions • confusing ‘prestige’ with ‘correctness’ • lack of linguistic background, understanding of languages and dialects • perception of group using language variety • perception of various races, ethnicities, religions • perception of people from various regions • perception of people of various socioeconomic statuses • etc. Characteristics of AAE AAE - Characteristics • AAE differs systematically from Mainstream American English (MAE). • Characteristics of AAE which differ from MAE regularly occur in other dialects/languages. • Not all varieties of AAE exhibit all of the aspects discussed below. • Only characteristics of AAE which differ from MAE are presented below. AAE - Phonology • R-Deletion • /ɹ/ is deleted unless before a vowel • e.g. ‘sore’ = ‘saw’; ‘poor’ = ‘Poe’ • also common in New York, Boston, England • L-Deletion • e.g. ‘toll’ = ‘toe’, ‘all’ = ‘awe’ • also happens in Delaware! • ‘folder’ => ‘foder’ AAE - Phonology • Consonant cluster reduction • e.g. -

321 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (Eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: Small Time Agents in a Global Arena

Index A Swedish iron Almenn landskipunarfræði , 40 Board of Mines , 55 Amina revolt global integration , 55 Aquambo nation , 266 market economy , 54 ethnic networks , 264 metal trades , 54 French soldiers , 264 Moravian mission , 265 rebels , 264 B 1733 revolt , 265 Bankhus site , 288–289 Slave Coast , 265 Berckentin Palace , 9 St. Thomas , 263 Brevis Commentarius de Islandia , 39 Atlantic economy Gammelbo to Calabar African traders , 59 C European slave trade and New World Charlotte Amalie port slavery , 60 archaeological exploration , 280 Gammelbo forgemen , 58 Bankhus site , 288–289 slave ships , 59 Caribbean market , 276 voyage iron , 58 cast iron , 279 ironworks Danish trade , 275 Bergslagen region , 55 historical documents , 276 bergsmän , 56 housing compounds, Government Hill , 279 bruks , 56 Magens House site Dannemora mine , 57 ceramics , 284 Dutch and British consumers , 58 Crown House , 283 osmund iron , 56 Danish fl uted lace porcelain , 284 pig iron , 56 excavated material remains , 285 Leufsta to Birmingham’s steel furnaces high-cost goods , 286 British manufacturers market , 64 ironwork , 286 common iron , 61 Moravian ware , 284 international market , 63 terraces , 285 iron quality , 64 urban garden , 287 järnboden storehouse , 63 nineteenth-century gates , 281 Öregrund Iron , 62 spatial analysis Walloon forging technique , 61 Blackbeard’s Castle , 282 Swedish economy , 64–66 bone button blanks , 283 M. Naum and J.M. Nordin (eds.), Scandinavian Colonialism and the Rise of Modernity: 321 Small Time Agents in a Global Arena, Contributions To Global Historical Archaeology 37, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4614-6202-6, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 322 Index Charlotte Amalie port (cont.) Greenland , 107–108 cultural meaning and intentions , 281 illegal trade interisland trade of goods and alcoholic beverages , 109 wares , 282 British faience plate , 109 social relations , 281 buy and discard practice , 110 transhipment/redistribution centre , 283 Disko Bay , 108 St. -

Trini Talk Or the Queen's English?

Copyright by Sarojani S. Mohammed 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Sarojani S. Mohammed Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Trini Talk or the Queen’s English? Navigating Language Varieties in the Post-Colonial, High Stakes Climate of “Standard Five” Classrooms in Trinidad Committee: Diane L. Schallert, Co-Supervisor Barbara G. Dodd, Co-Supervisor Lars Hinrichs Zena T. Moore Marilla D. Svinicki Brandon K. Vaughn Trini Talk or the Queen’s English? Navigating Language Varieties in the Post-Colonial, High Stakes Climate of “Standard Five” Classrooms in Trinidad by Sarojani S. Mohammed, S.B. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2008 Dedication To the newest source of inspiration in my life, my nephew, Henrik Åge Lundgård. Acknowledgements In many ways, this document represents the love and support of the village that raised me. I regret that I cannot express my gratitude to every person who has helped me along the way, but I appreciate this opportunity to acknowledge in print those who have devoted inordinate amounts of time and effort to ensure the completion of this degree, and this project in particular. To my parents, who knew that I could do this even before it was a dream of mine, I thank you for your love and patience, help and advice, and especially for your encouragement and support over the past 27 years. To my brother and sister, thanks for making me who I am, and loving me as I am. -

Kinematic Reconstruction of the Caribbean Region Since the Early Jurassic

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 102–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Kinematic reconstruction of the Caribbean region since the Early Jurassic Lydian M. Boschman a,⁎, Douwe J.J. van Hinsbergen a, Trond H. Torsvik b,c,d, Wim Spakman a,b, James L. Pindell e,f a Department of Earth Sciences, Utrecht University, Budapestlaan 4, 3584 CD Utrecht, The Netherlands b Center for Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, Sem Sælands vei 24, NO-0316 Oslo, Norway c Center for Geodynamics, Geological Survey of Norway (NGU), Leiv Eirikssons vei 39, 7491 Trondheim, Norway d School of Geosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, WITS 2050 Johannesburg, South Africa e Tectonic Analysis Ltd., Chestnut House, Duncton, West Sussex, GU28 OLH, England, UK f School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3YE, UK article info abstract Article history: The Caribbean oceanic crust was formed west of the North and South American continents, probably from Late Received 4 December 2013 Jurassic through Early Cretaceous time. Its subsequent evolution has resulted from a complex tectonic history Accepted 9 August 2014 governed by the interplay of the North American, South American and (Paleo-)Pacific plates. During its entire Available online 23 August 2014 tectonic evolution, the Caribbean plate was largely surrounded by subduction and transform boundaries, and the oceanic crust has been overlain by the Caribbean Large Igneous Province (CLIP) since ~90 Ma. The consequent Keywords: absence of passive margins and measurable marine magnetic anomalies hampers a quantitative integration into GPlates Apparent Polar Wander Path the global circuit of plate motions. -

Portuguese Folklore Sung by Malaccan Kristang Groups and the Issue of Decreolization

Portuguese Folklore Sung by Malaccan Kristang Groups and the Issue of Decreolization Mario Nunes IPOR, Macau Introduction Kristang is the denomination for the Portuguese-based creole still in use in Malacca. Fonns derived from Kristang spread to neighboring islands of the Indonesian Archipelago, but as far as I have been able to understand, they are almost extinct. Introduction to the present geographical location and extent of use of this creole as a daily means of verbal interaction by its native speakers was reported at the VIIieme Coll6que International des Etudes Creoles in Guadaloupe. (Nunes, 1996). The origin of Kristang goes back to the year 1511, when Alfonso de Al buquerque took the prosperous port of Malacca by force. We know for sure that there was a considerably large migration of Ceylonese Burghers to Mal acca, both during the Portuguese occupation as well as during the Dutch and British eras. As Kenneth David Jackson (1990) has shown us, the Ceylonese Burghers were and still are inheritors of a rich oral folklore, clearly based on 150 JURNAL BAHASA MODEN oral Portuguese medieval folklore themes. Just as Jackson did in Sri Lanka by identifying several types of Portuguese-based cantigas, so did Silva Rego (1942), who found evidence of such cantigas in Malacca. With reference to songs, he classifies them into three categories. the true Kristang songs, those of Malay origin, and the so-called europeanas, which were generally of En glish origin, either from popular films or famous singers. The pattern of communication of this community shows that generations have almost lost the knowledge of the ancient oral folklore traditions. -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

Preliminary Checklist of Extant Endemic Species and Subspecies of the Windward Dutch Caribbean (St

Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos, P.A.J. Bakker, R.J.H.G. Henkens, J. A. de Freitas, A.O. Debrot Wageningen University & Research rapport C067/18 Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species and subspecies of the windward Dutch Caribbean (St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and the Saba Bank) Authors: O.G. Bos1, P.A.J. Bakker2, R.J.H.G. Henkens3, J. A. de Freitas4, A.O. Debrot1 1. Wageningen Marine Research 2. Naturalis Biodiversity Center 3. Wageningen Environmental Research 4. Carmabi Publication date: 18 October 2018 This research project was carried out by Wageningen Marine Research at the request of and with funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality for the purposes of Policy Support Research Theme ‘Caribbean Netherlands' (project no. BO-43-021.04-012). Wageningen Marine Research Den Helder, October 2018 CONFIDENTIAL no Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Bos OG, Bakker PAJ, Henkens RJHG, De Freitas JA, Debrot AO (2018). Preliminary checklist of extant endemic species of St. Martin, St. Eustatius, Saba and Saba Bank. Wageningen, Wageningen Marine Research (University & Research centre), Wageningen Marine Research report C067/18 Keywords: endemic species, Caribbean, Saba, Saint Eustatius, Saint Marten, Saba Bank Cover photo: endemic Anolis schwartzi in de Quill crater, St Eustatius (photo: A.O. Debrot) Date: 18 th of October 2018 Client: Ministry of LNV Attn.: H. Haanstra PO Box 20401 2500 EK The Hague The Netherlands BAS code BO-43-021.04-012 (KD-2018-055) This report can be downloaded for free from https://doi.org/10.18174/460388 Wageningen Marine Research provides no printed copies of reports Wageningen Marine Research is ISO 9001:2008 certified. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

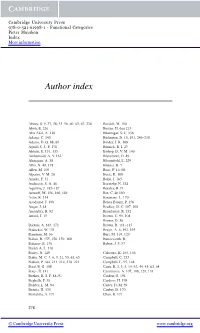

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

The University of Chicago the Creole Archipelago

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CREOLE ARCHIPELAGO: COLONIZATION, EXPERIMENTATION, AND COMMUNITY IN THE SOUTHERN CARIBBEAN, C. 1700-1796 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY TESSA MURPHY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2016 Table of Contents List of Tables …iii List of Maps …iv Dissertation Abstract …v Acknowledgements …x PART I Introduction …1 1. Creating the Creole Archipelago: The Settlement of the Southern Caribbean, 1650-1760...20 PART II 2. Colonizing the Caribbean Frontier, 1763-1773 …71 3. Accommodating Local Knowledge: Experimentations and Concessions in the Southern Caribbean …115 4. Recreating the Creole Archipelago …164 PART III 5. The American Revolution and the Resurgence of the Creole Archipelago, 1774-1785 …210 6. The French Revolution and the Demise of the Creole Archipelago …251 Epilogue …290 Appendix A: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of Dominica …301 Appendix B: Lands Leased to Existing Inhabitants of St. Vincent …310 A Note on Sources …316 Bibliography …319 ii List of Tables 1.1: Respective Populations of France’s Windward Island Colonies, 1671 & 1700 …32 1.2: Respective Populations of Martinique, Grenada, St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent c.1730 …39 1.3: Change in Reported Population of Free People of Color in Martinique, 1732-1733 …46 1.4: Increase in Reported Populations of Dominica & St. Lucia, 1730-1745 …50 1.5: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in the Lesser Antilles, 1626-1762 …57 1.6: Enslaved Africans Reported as Disembarking in Jamaica & Saint-Domingue, 1526-1762 …58 2.1: Reported Populations of the Ceded Islands c. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume).