Is Kamtok a Variety of English Or a Language in Its Own Right? Aloysius Ngefac, Loreto Todd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

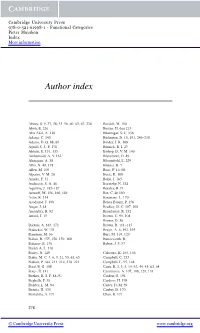

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Making Sense of "Bad English"

MAKING SENSE OF “BAD ENGLISH” Why is it that some ways of using English are considered “good” and others are considered “bad”? Why are certain forms of language termed elegant, eloquent, or refined, whereas others are deemed uneducated, coarse, or inappropriate? Making Sense of “Bad English” is an accessible introduction to attitudes and ideologies towards the use of English in different settings around the world. Outlining how perceptions about what constitutes “good” and “bad” English have been shaped, this book shows how these principles are based on social factors rather than linguistic issues and highlights some of the real-life consequences of these perceptions. Features include: • an overview of attitudes towards English and how they came about, as well as real-life consequences and benefits of using “bad” English; • explicit links between different English language systems, including child’s English, English as a lingua franca, African American English, Singlish, and New Delhi English; • examples taken from classic names in the field of sociolinguistics, including Labov, Trudgill, Baugh, and Lambert, as well as rising stars and more recent cutting-edge research; • links to relevant social parallels, including cultural outputs such as holiday myths, to help readers engage in a new way with the notion of Standard English; • supporting online material for students which features worksheets, links to audio and news files, further examples and discussion questions, and background on key issues from the book. Making Sense of “Bad English” provides an engaging and thought-provoking overview of this topic and is essential reading for any student studying sociolinguistics within a global setting. -

The Relationship of Nigerian English and Nigerian Pidgin in Nigeria: Evidence from Copula Constructions in Ice-Nigeria

journal of language contact 13 (2020) 351-388 brill.com/jlc The Relationship of Nigerian English and Nigerian Pidgin in Nigeria: Evidence from Copula Constructions in Ice-Nigeria Ogechi Florence Agbo Ph.D student, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany [email protected] Ingo Plag Professor of English Language and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Humani- ties, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany [email protected] Abstract Deuber (2006) investigated variation in spoken Nigerian Pidgin data by educated speakers and found no evidence for a continuum of lects between Nigerian Pidgin and English. Many speakers, however, speak both languages, and both are in close contact with each other, which keeps the question of the nature of their relationship on the agenda. This paper investigates 67 conversations in Nigerian English by educated speakers as they occur in the International Corpus of English, Nigeria (ice-Nigeria, Wunder et al., 2010), using the variability in copula usage as a test bed. Implicational scaling, network analysis and hierarchical cluster analysis reveal that the use of vari- ants is not randomly distributed over speakers. Particular clusters of speakers use par- ticular constellations of variants. A qualitative investigation reveals this complex situ- ation as a continuum of style, with code-switching as one of the stylistic devices, motivated by such social factors as formality, setting, participants and interpersonal relationships. Keywords Nigerian Pidgin – Nigerian English – code-switching – style-shifting – implicational scaling – network analysis – cluster analysis © Ogechi Agbo and Ingo Plag, 2020 | doi:10.1163/19552629-bja10023 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 10:21:27AM publication. -

Anala Lb. Straine 2016 Nr.1

ANALELE UNIVERSITĂŢII BUCUREŞTI LIMBI ŞI LITERATURI STRĂINE 2016 – Nr. 1 SUMAR • SOMMAIRE • CONTENTS LINGVISTIC Ă / LINGUISTIQUE / LINGUISTICS ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş, Romanian Aspectual Verbs: Control and Restructuring ............... 3 COSTIN-VALENTIN OANCEA, The Category of Number in Present-Day English(es): Variation and Context ............................................................................................ 25 LEAH NACHMANI, EFL Teachers’ Perspectives on Reading Acquisition within a Multi-Cultural Learning Environment .................................................................. 41 ANDREI A. AVRAM, Diagnostic Features of English Pidgins/Creoles: New Evidence from West African Pidgin English and Krio ........................................................ 55 MIHAI CRUDU, Zum Lexem Herr und zu dessen Auftauchen in Wortbildungen und Phrasemen ............................................................................................................... 79 CAMELIA M ĂDĂLINA ŞTEFAN, On Latin-Old Swedish Language Contact through Loanwords ............................................................................................................... 89 * Recenzii • Comptes rendus • Reviews .................................................................................. 105 Contributors ........................................................................................................................ 111 ROMANIAN ASPECTUAL VERBS: CONTROL AND RESTRUCTURING ELENA L ĂCĂTU Ş* Abstract The aim of the present paper is to investigate -

Creole and Pidgin Languages

Author's personal copy Provided for non-commercial research and educational use only. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This article was originally published in the International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial From Mufwene, S.S., 2015. Pidgin and Creole Languages. In: James D. Wright (editor-in-chief), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd edition, Vol 18. Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 133–145. ISBN: 9780080970868 Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. unless otherwise stated. All rights reserved. Elsevier Author's personal copy Pidgin and Creole Languages Salikoko S Mufwene, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA Ó 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Abstract The study of creoles and pidgins has been marked by controversy about how they emerged, whether they can be identified by their structural features, and how they stand genetically in relation to their lexifiers. There have also been disagreements about what contact-induced varieties count as creoles, whether expanded pidgins should be lumped together with them, otherwise what distinguishes both kinds of vernaculars from each other, and how other contact-induced language varieties can be distinguished from all the above. -

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity

Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity Karen Mattison Yabuno I. INTRODUCTION Hawaiian Creole English, commonly known as Pidgin, is widely spoken in Hawaii. In 2015, it was recognized by the US Census Bureau as a third official language of Hawaii, following English and Hawaiian(Laddaran, 2015). Pidgin is distinct and separate from Hawaii English(Drager, 2012), which is also widely spoken in Hawaii but not recognized as an official language of the state. Pidgin arose among immigrant groups on the pineapple plantations and was the dominant language of the workers’ children by the 1920’s(Tamura, 1993). Historically, an ability to speak Pidgin established one as ‘local’ to Hawaii, while English was seen to be part of the haole(Caucasian) identity (Drager, 2012). Although non-English speaking Caucasians also worked on the plantations, the term ‘local’ has come to mean those descended from Asian immigrant groups, as well as indigenous Hawaiians. These days, about half of the population of Hawaii speak Pidgin(Sakoda and Siegel, 2003). Caucasians born, raised, or residing in Hawaii may also understand and speak Pidgin. However, there can be a negative reaction to Caucasians speaking Pidgin, even when the Caucasians self-identify as ‘locals’. This is discussed in the YouTube video, Being White in Hawaii(Timahification, 2014), and parodied in the YouTube video, Hawaiian Haole(YouRight, 2016). Why is it offensive for a Caucasian to speak Pidgin? To answer this question, this paper will examine the parody video, Hawaiian Haole; ‘local’ ―189― Hawaiian Creole English and Caucasian Identity identity in Hawaii; and race in Hawaii. Finally, the viewpoints of three ‘local’ haole will be presented. -

Pidgins and Creoles

12/7/2015 LNGT0101 Announcements Introduction to Linguistics • HW 4 sent to your inboxes. Average score is 45/50. • Final HW is due today, and then you can celebrate. • Any questions on your final papers? Lecture #23 Dec 7th, 2015 2 Announcements Word play! • I’ll give out course response forms on Wednesday. So, please be there to fill them out! • Photo today? 3 4 Ambiguity again! Today’s agenda • Discussion of pidgins and creoles. 5 6 1 12/7/2015 Language contact What is a pidgin? Creating language out of thin air: What is a creole? The case of Pidgins and Creoles 7 8 Origin of Hawaiian Pidgin A sample of Hawaiian Pidgin • http://sls.hawaii.edu/pidgin/whatIsPidgin.php • http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui‐ Magazine/July‐August‐2015/Da‐State‐of‐da‐ State/ 9 10 How about we listen to this English‐based speech variety? • English‐based speech variety • How much did you understand? • Maybe we can try reading. Not sure it’ll help, but let’s try. 11 12 2 12/7/2015 Emergence of Pidgins and Creoles Pidginization areas • A pidgin is a system of communication used by people who do not know each other’s languages but need to communicate with one another for trading or other purposes. • By definition, then, a pidgin is not a natural language. It’s a made‐up “makeshift” language. Notice, crucially, that it does not have native speakers. 13 14 The lexicons of Pidgins are typically based Pidgins are linguistically on some dominant language simplified systems • While a pidgin is used by speakers of different • As you should expect, pidgins are very simple languages, it is typically based on the lexicon of what in their linguistic properties. -

ENG 300 – the History of the English Language Wadhha Alsaad

ENG 300 – The History of The English Language Wadhha AlSaad 13/4/2020 Chap 4: Middle English Lecture 1 Why did English go underground (before the Middle English)? The Norman Conquest in 1066, England was taken over by a French ruler, who is titled prior to becoming the king of England, was the duke of Normandy. • Norman → Norsemen (Vikings) → the men from the North. o The Normans invited on the Viking to stay on their lands in hope from protecting them from other Vikings, because who is better to fight a Viking then a Viking themselves. • About 3 hundred years later didn’t speak their language but spoke French with their dialect. o Norman French • William, the duke of Normandy, was able to conquer most of England and he crowned himself the king. o The Normans became the new overlord and the new rulers in England. ▪ They hated the English language believing that is it unsophisticated and crude and it wasn’t suitable for court, government, legal proceedings, and education. ▪ French and Latin replaced English: • The spoken language became French. • The written language, and the language of religion became Latin. ▪ The majority of the people who lived in England spoke English, but since they were illiterate, they didn’t produce anything so there weren’t any writing recordings. ▪ When it remerges in the end 13th century and the more so 14th century, it is a very different English, it had something to do with inflection. • Inflection: (-‘s), gender (lost in middle English), aspect, case. ▪ When Middle English resurfaces as a language of literature, thanks to Geoffrey Chaucer who elevated the vernaculars the spoken language to the status of literature, most of the inflections were gone. -

Pidgins and Creoles

Chapter 7: Contact Languages I: Pidgins and Creoles `The Negroes who established themselves on the Djuka Creek two centuries ago found Trio Indians living on the Tapanahoni. They maintained continuing re- lations with them....The trade dialect shows clear traces of these circumstances. It consists almost entirely of words borrowed from Trio or from Negro English' (Verslag der Toemoekhoemak-expeditie, by C.H. De Goeje, 1908). `The Nez Perces used two distinct languages, the proper and the Jargon, which differ so much that, knowing one, a stranger could not understand the other. The Jargon is the slave language, originating with the prisoners of war, who are captured in battle from the various neighboring tribes and who were made slaves; their different languages, mixing with that of their masters, formed a jargon....The Jargon in this tribe was used in conversing with the servants and the court language on all other occasions' (Ka-Mi-Akin: Last Hero of the Yakimas, 2nd edn., by A.J. Splawn, 1944, p. 490). The Delaware Indians `rather design to conceal their language from us than to properly communicate it, except in things which happen in daily trade; saying that it is sufficient for us to understand them in that; and then they speak only half sentences, shortened words...; and all things which have only a rude resemblance to each other, they frequently call by the same name' (Narratives of New Netherland 1609-1664, by J. Franklin Jameson, 1909, p. 128, quoting a comment made by the Dutch missionary Jonas Micha¨eliusin August 1628). The list of language contact typologies at the beginning of Chapter 4 had three entries under the heading `extreme language mixture': pidgins, creoles, and bilingual mixed lan- guages. -

Sociolinguistics of the Varieties of West African Pidgin Englishes—A

Studies in English Language Teaching ISSN 2372-9740 (Print) ISSN 2329-311X (Online) Vol. 4, No. 4, 2016 www.scholink.org/ojs/index.php/selt Sociolinguistics of the Varieties of West African Pidgin Englishes—A Review Edward Owusu1,3*, Samuel Kyei Adoma1 & Daniel Oti Aboagye2 1 Department of Communication Studies, Sunyani Technical University, Sunyani, Ghana 2 Counselling Unit, Sunyani Technical University, Sunyani, Ghana 3 Department of Linguistics, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana * Edward Owusu, E-mail: [email protected] Received: October 26, 2016 Accepted: November 6, 2016 Online Published: November 13, 2016 doi:10.22158/selt.v4n4p534 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.22158/selt.v4n4p534 Abstract Language contact is a key issue in the field of sociolinguistics. One notable phenomenon in the field of language contact is Pidgin English. Historically, Pidgin began as a language marked by traditional interference used chiefly by the prosperous and privileged sections of a community, represented by the unskilled and illiterate class of the society (Quirk et al., 1985). However, nowadays, it has gained status in some communities to the extent that it has become the mother-tongue of such communities. This paper, therefore, investigates the sociolinguistics of the multiplicity of West African Pidgins of Cameroon, Nigeria and Ghana against some sociolinguistic variables of gender, attitudes, code switching, borrowing, slang, and domains of language use. The paper has been structured into two main parts. The first section contains the reviews/synopses of the various papers or works that have been used for the study. The second section deals with a discussion on the prominent sociolinguistic variables found in the various papers. -

The Changing Status of Nigerian Pidgin

International Journal of Language and Literature June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 208-216 ISSN: 2334-234X (Print), 2334-2358 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2015. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijll.v3n1a26 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijll.v3n1a26 Beyond Barriers: The Changing Status of Nigerian Pidgin Jane Nkechi Ifechelobi 1 & Chiagozie Uzoma Ifechelobi 2 Abstract It is a sociolinguistic reality that any living language has the tendency to adapt to the environment in which it operates whether the language is spoken as a first or second language. The English language has served the nation Nigeria in much capacity – as the language of education, commerce, politics, administration etc. Nigeria as a multilingual nation with about four hundred or so ethno-linguistic groups each with an indigenous language has the English language superimposed on them as the official language. So English in Nigeria is continuously undergoing various processes of domestication, naturalization and acculturation within each ethno-linguistic context. In a situation where two speech communities without a common language come together for a certain purpose, a means of communication emerges. The emergent language is usually referred to as a contact language. This paper takes a cursory look at the evolution of Nigeria Pidgin over the years. Keywords: Nigerian Pidgin, Broken English; superstrate language, inter-ethnic communication, indigenous languages, lingua franca Introduction The primary purpose of language is communication. It is used to communicate an incredible number of things. We cannot make sense of an idea without being able to make sense of the language.